Adriaen Thomasz. Key stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the rich tapestry of 16th-century Flemish art. Active primarily in Antwerp during a period of profound religious and political upheaval, Key carved out a distinguished career as a painter, draughtsman, and printmaker. Born around 1544, his life and work bridged the late Renaissance sensibilities with the emerging undercurrents that would eventually lead to the Baroque. He passed away sometime after June 1589, with some sources suggesting as late as 1599. Key is particularly celebrated for his insightful portraiture and his compelling religious compositions, demonstrating a remarkable ability to adapt his art to the changing spiritual landscape of his time.

Early Life, Training, and the Antwerp Milieu

While the precise details of Adriaen Thomasz. Key's earliest years and birthplace remain somewhat obscure, it is widely accepted that he was of Dutch origin. His artistic formation, however, took place in Antwerp, then the bustling economic and cultural heart of the Low Countries. This city was a magnet for artists, a vibrant center of production and trade in artworks, and home to influential guilds like the Guild of Saint Luke, which regulated the training and practice of painters.

Key's most formative experience was his apprenticeship and subsequent work in the studio of Willem Key (c. 1515 – 1568). Willem Key was himself a highly respected painter of portraits and historical subjects, a student of Lambert Lombard, and a contemporary of artists like Frans Floris. The relationship between Adriaen and Willem is thought to be that of a nephew to an uncle, or at least a close familial connection, though definitive proof is elusive. Regardless of the exact kinship, Adriaen Thomasz. Key not only absorbed the technical skills and stylistic tendencies of his master but also eventually inherited the workshop's mantle, taking over its operations after Willem Key's death in 1568. This succession speaks volumes about Adriaen's talent and the esteem in which he was held.

The artistic environment of Antwerp in the mid-16th century was dynamic. It was a place where the legacy of earlier Flemish masters like Jan van Eyck, Rogier van der Weyden, and Hans Memling was still palpable, but also where Italian Renaissance influences, brought back by artists who had travelled south (the "Romanists" like Jan Gossaert, Maerten van Heemskerck, and Frans Floris), were being assimilated and transformed. Portraiture was in high demand, fueled by a wealthy merchant class and nobility eager to have their likenesses preserved. Artists like Anthonis Mor (Antonio Moro), who achieved international fame, set a high standard for courtly and aristocratic portraiture.

The Shadow of the Reformation: Art in a Time of Iconoclasm

Adriaen Thomasz. Key's career unfolded against the backdrop of one of the most tumultuous periods in European history: the Protestant Reformation and its profound impact on the Low Countries. The rise of Calvinism, with its austere theological stance and suspicion of religious imagery, led to waves of iconoclasm (the "Beeldenstorm" or "Iconoclastic Fury"), particularly in 1566. Churches were stripped of their statues, altarpieces, and stained glass, as reformers sought to purify worship spaces from what they considered idolatry.

This religious schism had a direct and dramatic effect on artists. The traditional patronage of the Catholic Church, which had commissioned grand altarpieces and devotional images for centuries, significantly diminished in Protestant-leaning areas. Artists like Key had to navigate this complex and often dangerous environment. They needed to find new patrons, adapt their subject matter, or find ways to create religious art that was acceptable to a broader, more religiously diverse, or at least cautious, audience.

Key's response to this challenge is evident in his work. While he continued to paint religious subjects, there is often a discernible shift in emphasis. His religious paintings tend towards a more restrained, humanized depiction of sacred figures, avoiding overtly ostentatious or dogmatically specific Catholic iconography that might provoke Protestant ire. This approach can be seen as an attempt to find a "via media," a middle way that could appeal to both Catholic patrons who remained and perhaps even to more moderate Protestants, or at least not actively offend them. His work reflects a search for a new visual language capable of conveying spiritual depth without relying on the elaborate symbolic apparatus of pre-Reformation art. This was a challenge faced by many of his contemporaries, including painters like Maerten de Vos and Ambrosius Francken, who also had to adapt their output.

Artistic Style and Thematic Concerns

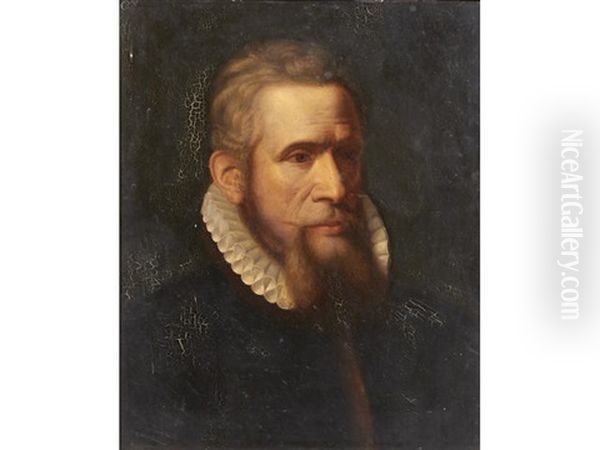

Adriaen Thomasz. Key's artistic style is characterized by a sober realism, meticulous attention to detail, and a remarkable ability to capture the psychological presence of his sitters. His technique was refined, with smooth brushwork and a subtle handling of light and shadow that lent volume and life to his figures.

In his portraiture, Key excelled at conveying not just the physical likeness but also the character and social standing of his subjects. His portraits are often direct and unidealized, presenting individuals with a sense of dignity and gravitas. He paid close attention to the rendering of textures – the sheen of silk, the richness of velvet, the glint of metal – which not only demonstrated his technical virtuosity but also served to indicate the status of the sitter. His palette was often somewhat restrained, favoring rich but not overly bright colors, which contributed to the serious and thoughtful mood of many of his portraits. This approach aligns him with a strong Netherlandish tradition of realistic portraiture, but with his own distinct, somewhat austere, elegance.

His religious paintings, while perhaps less numerous than his portraits, are equally compelling. They often exhibit a quiet emotional intensity. Key's figures are typically well-drawn and solid, their gestures and expressions conveying piety or contemplation without excessive drama. He managed to imbue these scenes with a sense of spiritual significance even while adhering to the more subdued aesthetic that the times increasingly demanded. His compositions are generally balanced and clear, focusing the viewer's attention on the core narrative or devotional message. The influence of Italian Renaissance composition can sometimes be felt, but it is always tempered by a distinctly Northern European sensibility.

Masterworks: The Portrait of William I, Prince of Orange

Undoubtedly, Adriaen Thomasz. Key's most famous and historically significant work is his Portrait of William I, Prince of Orange, also known as William the Silent. Painted around 1579, this iconic image depicts the principal leader of the Dutch Revolt against Spanish rule. Several versions of this portrait exist, with notable examples housed in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam and the Mauritshuis in The Hague.

The portrait is a masterful character study. William I is presented in a three-quarter view, dressed in dark, sober attire, including a characteristic small cap (calotte) and a ruff, with a cloak that adds to his dignified presence. Key does not flatter or idealize his subject; instead, he presents a man burdened by responsibility, his expression serious and contemplative, perhaps tinged with weariness. The meticulous rendering of his features, including the lines on his forehead and around his eyes, speaks to Key's commitment to realism. The dark, neutral background focuses all attention on the Prince, enhancing his psychological presence.

The creation of this portrait was a significant commission, reflecting Key's status as a leading portraitist. William the Silent was a pivotal figure in the struggle for Dutch independence, and his image was crucial for political and propaganda purposes. Key's portrayal became one of the definitive likenesses of the Prince, widely copied and disseminated.

The painting's history also touches upon some of the complexities of art conservation and historical interpretation. Restorations of versions of this portrait have revealed later additions and overpainting, prompting discussions among art historians and conservators about the artist's original intent and how best to present such historically layered artworks. For instance, debates have arisen regarding whether to retain later additions that have become part of the painting's historical identity or to attempt to return it to its earliest known state.

Other Notable Works and Commissions

Beyond the celebrated portrait of William I, Adriaen Thomasz. Key produced a range of other significant works. Among these are altarpiece wings, which demonstrate his skill in religious narrative and devotional imagery. An example that garnered considerable attention in recent times involved two altarpiece wings depicting Saint Jerome and a male donor, which were sold at the TEFAF art fair in 2021 for a reported €3 million. Such a sale underscores the enduring market value and art historical appreciation for Key's work. These wings would originally have flanked a central panel, likely depicting a major religious scene, and their survival highlights the fragmented nature of much of the art from this period due to iconoclasm or later dismantling.

Key also painted portraits of other prominent individuals. His Portrait of Margaret of Parma, who served as Regent of the Netherlands for her half-brother Philip II of Spain, is another example of his ability to capture the likeness of powerful figures. Such commissions from the ruling elite further attest to his reputation.

His religious oeuvre, though perhaps less documented than his portraits, would have included scenes from the life of Christ, the Virgin Mary, and saints, adapted, as mentioned, to the prevailing religious climate. The challenge for artists like Key was to continue producing meaningful religious art in an era when the very nature and purpose of such art were being questioned. His success in this regard is a testament to his skill and adaptability. He, like many artists of his generation such as Pieter Pourbus in Bruges or Gillis Mostaert in Antwerp, had to find a path that respected new theological sensitivities while retaining artistic integrity.

The Enigma of Key's Later Career and Artistic Circle

Despite his evident success, particularly in the 1570s and early 1580s, aspects of Adriaen Thomasz. Key's later career remain somewhat enigmatic. After the Fall of Antwerp to Spanish forces under Alexander Farnese, Duke of Parma, in 1585, the city experienced a significant decline as many Protestant merchants, artisans, and intellectuals fled north to the newly independent Dutch Republic. This exodus included artists, and it's possible that the changing political and economic landscape affected Key's patronage and output.

Art historical records from the Antwerp Guild of Saint Luke show fewer documented works by Key after this period, leading some scholars to speculate that his career may have waned or that he perhaps left Antwerp, though evidence for the latter is lacking. It's also possible that he continued to work but that records are simply incomplete. The precise date and circumstances of his death are not definitively known, with sources generally placing it after June 1589.

Regarding his relationships with other contemporary painters, his connection with Willem Key is the most clearly established. As the inheritor of Willem Key's studio, he would have been part of a lineage and a network of artistic practice. Antwerp was a city where artists often collaborated, shared apprentices, and competed for commissions. While specific documented collaborations or rivalries involving Adriaen Thomasz. Key are scarce, he would undoubtedly have been aware of and interacted with other leading Antwerp painters of his generation. These might have included figures like Maerten de Vos, a prolific painter of religious and mythological scenes, the Francken family of painters (such as Frans Francken the Elder), and portraitists like Frans Pourbus the Elder. The artistic community was relatively close-knit, and reputations were built through both skill and professional conduct.

The influence of earlier masters like Pieter Bruegel the Elder, who died in 1569 just as Key was establishing his independent career, would also have been part of the artistic atmosphere, though Bruegel's focus on peasant scenes and landscapes differed significantly from Key's primary genres. However, Bruegel's keen observation of humanity and his subtle commentaries on his times might have resonated with Key's own thoughtful approach to his subjects.

Legacy and Historical Significance

Adriaen Thomasz. Key's legacy is primarily that of a highly skilled and sensitive portraitist who captured the likenesses of some of the most important figures of his era. His Portrait of William I, Prince of Orange remains an enduring image in Dutch national consciousness. His ability to convey character with a sober realism places him among the significant portrait painters of the 16th-century Netherlands.

His religious works are also important for understanding the artistic responses to the Reformation. Key demonstrated an ability to create devotional art that was both spiritually resonant and adaptable to the changing theological landscape. He navigated the difficult path between traditional Catholic iconography and the iconoclastic tendencies of Calvinism, producing works that often emphasized the human and emotional aspects of religious experience. This approach was shared by other artists who sought to maintain a role for religious art in a divided society.

Art historians note that Key's innovative concepts and refined technique were highly regarded, even influencing later masters. The suggestion that Peter Paul Rubens, a towering figure of the subsequent Baroque era, held Key's work in high esteem indicates the lasting quality and impact of his art. Rubens, who was born in 1577, would have been a young, aspiring artist as Key's career was concluding, and he would have been familiar with the work of established Antwerp masters.

In the broader sweep of art history, Adriaen Thomasz. Key can be seen as a transitional figure. He upheld the strong traditions of Flemish realism and craftsmanship inherited from artists like Jan van Eyck and Anthonis Mor, while also responding to the profound cultural and religious shifts of his own time. His work provides a valuable window into the artistic, political, and spiritual life of the 16th-century Low Countries. While perhaps not as universally recognized today as some of his contemporaries like Pieter Bruegel the Elder, or later Dutch Golden Age masters such as Rembrandt van Rijn or Johannes Vermeer (who are often cited in academic comparisons for "master-class" quality), Key's contributions are increasingly appreciated by scholars and collectors.

The ongoing research into his oeuvre, including technical studies of his paintings and investigations into his patronage, continues to shed light on his career and his place within the Netherlandish school. The high prices his works can command at auction, as seen with the TEFAF sale, further attest to his recognized importance.

Conclusion: A Master of His Time

Adriaen Thomasz. Key was an artist of considerable talent and significance, a master of portraiture whose works offer profound insights into the personalities and the era he depicted. His religious paintings reflect a thoughtful engagement with the spiritual crises of the 16th century, demonstrating an ability to adapt and innovate in a challenging environment. Working in the shadow of his esteemed relative Willem Key, he forged his own distinct artistic identity, characterized by meticulous technique, psychological depth, and a sober elegance.

From the bustling studios of Antwerp, Adriaen Thomasz. Key produced a body of work that captured the likenesses of key historical figures like William the Silent and navigated the complex demands of religious art during the Reformation. His legacy, though perhaps quieter than some of the more flamboyant figures of art history, is one of enduring quality and historical importance. He remains a testament to the resilience and adaptability of artists in times of profound change, and his paintings continue to speak to us across the centuries with their quiet dignity and masterful execution. His contributions enrich our understanding of Flemish art and the complex cultural currents of the late Renaissance in Northern Europe, standing alongside the achievements of artists from Albrecht Dürer in Germany to Titian in Venice, who also defined this transformative period in European art.