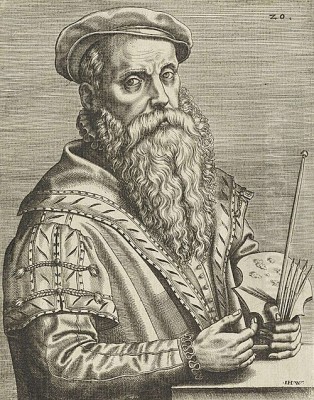

Willem Key, born around 1515 in Breda and deceased in Antwerp in 1568, stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, master of the Netherlandish Renaissance. Active primarily in Antwerp, the bustling artistic and commercial hub of Northern Europe during the 16th century, Key distinguished himself as a painter of refined portraits and compelling religious compositions. His oeuvre reflects a sophisticated synthesis of the rich indigenous artistic traditions of the Low Countries with the innovative spirit and classical ideals emanating from the Italian Renaissance, positioning him as a key transitional figure and an important innovator of his time.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Willem Key's journey into the world of art began in his birthplace of Breda, a town in the Duchy of Brabant. While details of his earliest years are scarce, it is documented that by 1529, he had moved to Antwerp to embark on his formal artistic training. He entered the workshop of Pieter Coecke van Aelst, a prominent and versatile artist known for his paintings, tapestry designs, and architectural treatises. Coecke van Aelst himself had traveled to Italy and Constantinople, and his workshop would have exposed the young Key to a broad range of artistic currents, including the burgeoning influence of Italian Renaissance art.

After his initial apprenticeship, Key sought further refinement of his skills. Around 1540, he, along with Frans Floris de Vriendt – who would become one of Antwerp's leading Romanists – traveled to Liège. There, they studied under the tutelage of Lambert Lombard. Lombard was a highly respected painter, architect, and humanist scholar, renowned for his deep understanding of classical antiquity and Italian art, having spent time in Rome. This period of study under Lombard was crucial, further steeping Key in the principles of Italian Renaissance aesthetics, including anatomical accuracy, classical proportion, and harmonious composition, which he would later integrate into his distinctly Netherlandish sensibility.

Establishment and Success in Antwerp

Having completed his extensive training, Willem Key established himself permanently in Antwerp. In 1540, a significant year marking his advanced studies, he was also admitted as a master into the prestigious Guild of Saint Luke in Antwerp. Membership in the guild was essential for any artist wishing to practice independently, take on apprentices, and sell their work in the city. Key's acceptance signifies his recognized competence and readiness to embark on a professional career.

Key rapidly achieved considerable success. He became a highly sought-after artist, particularly for his portraiture, which was praised for its verisimilitude and psychological insight. His clientele likely included wealthy merchants, clergy, and nobility, reflecting Antwerp's status as a cosmopolitan center of commerce. His prosperity is evidenced by the fact that he resided in a large house situated near the city's exchange, a prime location indicative of his comfortable financial standing.

His personal life also saw him integrate into the fabric of Antwerp society. He married Johanna Reynsdoek, and together they had a daughter, Susanna Key. Susanna would later marry the artist Huybrecht Beuckelaer, further connecting Willem Key's family to the artistic circles of Antwerp. Huybrecht was the brother of Joachim Beuckelaer, another notable Antwerp painter known for his market and kitchen scenes.

Artistic Style and Influences

Willem Key's artistic style is characterized by a masterful blend of Northern European realism and Italianate grace. He inherited the meticulous attention to detail, rich textures, and luminous oil glazes that were hallmarks of the Early Netherlandish tradition, exemplified by masters like Jan van Eyck and Rogier van der Weyden. However, his exposure to Italian art, both through his teachers and likely through prints and imported artworks, profoundly shaped his approach to form, composition, and idealization.

His figures often possess a sculptural quality and an elegant poise that recall Italian High Renaissance models, perhaps influenced by artists like Raphael or Andrea del Sarto. Yet, Key never fully abandoned the Northern penchant for individualized likeness and tangible reality. In his portraits, this resulted in depictions that were both dignified and intimately personal. His palette was often rich and harmonious, with a subtle use of color to model form and convey mood.

Compared to his contemporary and fellow Lombard student, Frans Floris, Key's style is often described as more restrained and elegant. While Floris embraced a more dynamic and muscular Italianate manner, Key's work tends towards a quieter, more ordered classicism. He was considered part of the "Antwerp School," which, during this period, was actively grappling with and assimilating Italian influences. His work demonstrates a soft modeling of figures and strong, clear lines, often incorporating classical architectural elements or motifs.

Major Themes and Representative Works

Willem Key's artistic production spanned two primary genres: portraiture and religious painting. In both, he demonstrated considerable skill and innovation.

Portraiture:

Key was highly esteemed as a portraitist. His ability to capture not only the physical likeness but also the character and social standing of his sitters made him a favorite among Antwerp's elite.

One of his notable early works is the Portrait of a Man dated 1543. This painting is significant for its introduction of a column as a background element, a motif often used in Italian Renaissance portraiture to lend an air of classical dignity and importance to the sitter. The man is depicted with a direct gaze, his features rendered with precision, and his attire detailed with care, reflecting his status.

Another important example is the Portrait of a Woman from 1548. This work showcases Key's skill in rendering the soft textures of fabric and flesh, and his sensitive handling of the interplay between the figure and the surrounding space. The woman's calm demeanor and the refined execution of the painting are characteristic of Key's mature portrait style.

The Verona Couple (also known as Portrait of a Man and Woman), dated 1556, is another significant work. It demonstrates Key's ability to create a dynamic interplay between two figures within a single composition, subtly conveying their relationship and individual personalities. Such double portraits were becoming increasingly popular, and Key's contribution shows his innovative approach to the genre. He was known to charge substantial sums for his portraits; one account mentions him receiving forty gold coins for a portrait of a cardinal, a testament to his high regard.

Religious Paintings:

While many of his religious works were tragically lost, those that survive or are known through copies attest to his skill in this genre as well. Key created altarpieces and devotional paintings that often featured dramatic compositions and emotionally resonant figures.

Perhaps his most famous religious work is The Last Supper, believed to have been painted around 1560. This large and complex composition, now in Dordrecht, depicts the poignant moment of Christ's announcement of his betrayal. The apostles are shown reacting with varied emotions, and the figure of Saint John is particularly notable for its gentle, sorrowful expression. The painting is also remarkable for its innovative inclusion of everyday details, such as a basket maker and a cooper, which add a layer of contemporary realism to the sacred scene. For a time, this work was misattributed to Antoon van den Broeck, but scholarly consensus now firmly assigns it to Key.

Other religious subjects Key is known to have painted include the Holy Family and scenes from the Passion of Christ. A Penance of St. Peter, whose attribution was confirmed by the discovery of his signature, further showcases his ability to convey deep religious feeling through expressive figures and carefully constructed settings. These works would have been commissioned for churches, private chapels, or devout patrons, serving as focal points for prayer and contemplation.

The Beeldenstorm and the Loss of Artworks

The mid-16th century in the Low Countries was a period of intense religious and political turmoil, culminating in the Beeldenstorm, or Iconoclastic Fury, of 1566. This wave of Calvinist-led destruction saw mobs storming churches and monasteries, smashing stained glass windows, defacing sculptures, and destroying paintings they deemed idolatrous. Antwerp, a city with a significant Protestant population, was heavily affected by these events.

For an artist like Willem Key, who produced a substantial body of religious work, the Beeldenstorm was devastating. Many of his altarpieces and devotional paintings, created for ecclesiastical settings, were undoubtedly destroyed during these iconoclastic riots. This loss makes a complete assessment of his religious oeuvre challenging, as we are left with only a fraction of what he likely produced. The surviving works and contemporary accounts, however, indicate that his religious paintings were highly valued for their artistic merit and devotional power. The destruction highlights the precariousness of art in times of social upheaval and the tragic loss of cultural heritage.

The Duke of Alba and Key's Demise: A Tragic Anecdote

A particularly poignant and dramatic story surrounds Willem Key's final days, linking his death directly to the turbulent political climate. The Spanish King Philip II, determined to suppress Protestantism and assert royal authority in the Netherlands, appointed Fernando Álvarez de Toledo, the 3rd Duke of Alba, as governor-general in 1567. Alba instituted a brutal regime, establishing the "Council of Troubles" (colloquially known as the "Council of Blood"), which condemned thousands to death.

According to the early art historian Karel van Mander in his Schilder-boeck (1604), Willem Key was commissioned to paint a portrait of the Duke of Alba. While working on this portrait, or shortly thereafter, Key supposedly overheard conversations or learned of the impending executions of prominent noblemen, including the Counts of Egmont and Hoorn, who were beheaded in Brussels in June 1568. Van Mander recounts that Key was so profoundly distressed and filled with grief by this news and the general atmosphere of terror that he fell ill and died on the very same day as the executions, June 5, 1568.

While the exact cause and timing of his death may be embellished by historical anecdote, the story powerfully illustrates the impact of the era's brutal realities on its artists. It paints a picture of Key as a sensitive individual deeply affected by the suffering around him. His death at the relatively young age of about fifty-three cut short a distinguished career.

Contemporaries and the Artistic Milieu of Antwerp

Willem Key operated within one of Europe's most vibrant artistic centers. Antwerp in the mid-16th century was teeming with talent, and artists frequently interacted, competed, and influenced one another. Key's teachers, Pieter Coecke van Aelst and Lambert Lombard, were themselves significant figures who helped shape the artistic landscape.

His fellow student under Lombard, Frans Floris, became a dominant force in Antwerp, known for his large-scale mythological and religious scenes in a robust Italianate style. While Key and Floris shared a common educational background, their artistic paths diverged, with Key cultivating a more refined and less overtly dramatic manner.

Other notable contemporaries in Antwerp included Pieter Bruegel the Elder, whose genre scenes and landscapes offered a very different, though equally powerful, vision of Netherlandish life and morality. While their subject matter differed significantly, both Key and Bruegel were masters of their respective domains. Market and kitchen scene painters like Joachim Beuckelaer (brother of Key's son-in-law) and Pieter Aertsen also contributed to the diversity of Antwerp's artistic output. Portraitists like Anthonis Mor (Antonio Moro), who achieved international fame working for the Spanish court, set a high standard for courtly portraiture, a field in which Key also excelled, albeit primarily for a local clientele.

The Guild of Saint Luke provided a framework for these artists, regulating their trade and fostering a sense of community, though rivalries undoubtedly existed. The presence of numerous printers and publishers in Antwerp also facilitated the dissemination of artistic ideas through engravings, making Italian and classical models more widely accessible. Key's work, therefore, should be seen within this dynamic context of artistic exchange, innovation, and the constant negotiation between local traditions and foreign influences. Other painters like Maerten de Vos, also a prolific Antwerp artist working in a style influenced by Italian art, particularly Venetian, were part of this rich environment.

Attribution and Scholarly Reception

Like many artists of his era, Willem Key did not consistently sign his works, which has led to challenges in attribution. Art historical scholarship has played a crucial role in identifying and cataloging his oeuvre. As mentioned, his masterpiece, The Last Supper, was for a time attributed to Antoon van den Broeck before meticulous stylistic analysis and documentary research restored it to Key. Similarly, the Penance of St. Peter was only definitively attributed to him after his signature was discovered.

These instances highlight the ongoing work of art historians in refining our understanding of 16th-century Netherlandish painting. Distinguishing Key's hand from that of his workshop assistants, his followers, or other contemporary artists working in similar styles can be complex. For example, Adriaen Thomasz. Key, believed to be a relative (possibly a nephew) and perhaps a pupil, continued Willem's portrait style, sometimes leading to confusion in attributions between the two. Adriaen Thomasz. Key became a prominent portraitist in his own right after Willem's death.

Despite these challenges, Willem Key is recognized by scholars as an artist of considerable talent and importance. His ability to imbue his portraits with a sense of quiet dignity and psychological depth, and his skill in creating harmonious and emotionally engaging religious compositions, secure his place in the annals of art history. His work is seen as representing a particular strand of Romanism in the Netherlands, one that favored elegance and clarity over overt dynamism.

Legacy and Influence

Willem Key's influence extended beyond his lifetime. His refined portrait style, which successfully blended Netherlandish precision with Italianate composure, had an impact on subsequent generations of portrait painters in the Low Countries. While perhaps not as overtly revolutionary as some of his contemporaries, his emphasis on subtle characterization and elegant presentation resonated with patrons and fellow artists.

His most direct artistic heir was Adriaen Thomasz. Key, who successfully carried on the tradition of portrait painting established by Willem, adapting it to the changing tastes of the later 16th century. More broadly, Willem Key's contributions to the development of portraiture in Antwerp helped lay the groundwork for the extraordinary achievements of 17th-century Flemish masters like Peter Paul Rubens and Anthony van Dyck. While their styles were more baroque and flamboyant, the tradition of insightful and technically brilliant portraiture that Key helped to foster was an important part of their artistic heritage.

The tragic loss of many of his religious works due to the Beeldenstorm makes it harder to fully assess his impact in that genre. However, the surviving examples demonstrate a high level of skill and a capacity for creating compelling narrative compositions that would have been admired and potentially emulated by other artists.

Conclusion: An Enduring Master of the Northern Renaissance

Willem Key emerges from the historical record as a distinguished and successful artist who played a significant role in the Netherlandish Renaissance. His life and career were shaped by the dynamic artistic exchanges between Northern Europe and Italy, as well as by the profound religious and political upheavals of his time. As a master portraitist, he captured the likenesses of Antwerp's citizenry with sensitivity and elegance, leaving behind a valuable record of the individuals who populated this vibrant metropolis. As a painter of religious subjects, he created works of devotional power and artistic sophistication, though many were tragically lost.

His ability to synthesize the meticulous realism of the Netherlandish tradition with the classical ideals and compositional harmony of the Italian Renaissance resulted in a distinctive and influential artistic voice. Though perhaps overshadowed in popular imagination by some of his more flamboyant contemporaries, Willem Key's contribution to the art of the 16th century is undeniable. He remains a testament to the rich artistic culture of Antwerp and a pivotal figure in the ongoing dialogue between Northern and Southern European art. His surviving works continue to be admired for their technical brilliance, their quiet dignity, and their insightful portrayal of the human spirit.