Introduction: A Pivotal Figure in Italian Art

Agostino Carracci stands as a significant figure in the transition from the late Renaissance Mannerist style to the burgeoning Baroque era in Italy. Born in Bologna on August 16, 1557, he was a key member of the Carracci family dynasty of artists, which included his younger, more famous brother Annibale Carracci, and their cousin Ludovico Carracci. Together, they spearheaded a reform movement in Italian art, challenging the prevailing artistic conventions and advocating for a return to naturalism combined with the study of High Renaissance masters. Agostino's multifaceted career encompassed painting, printmaking, and teaching, leaving a distinct mark on the art of his time and influencing subsequent generations, particularly through his prolific work as an engraver and his role in founding a groundbreaking art academy.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Bologna

Agostino's artistic journey began not with painting, but with an apprenticeship as a goldsmith and metal engraver. This early training provided him with a meticulous technical foundation that would prove invaluable throughout his career, especially in his later printmaking endeavors. However, his interests soon shifted towards painting. He sought guidance from established artists, initially studying with the painter Prospero Fontana, a prominent figure in the Bolognese school known for his Mannerist style. He also studied under Bartolomeo Passerotti and reportedly worked with Domenico Tibaldi.

Recognizing his nephew's potential, Ludovico Carracci, who was slightly older and already establishing himself as a painter, took Agostino under his wing. Ludovico encouraged a more rigorous approach based on drawing from life and studying the great masters of the past. Agostino's development was further enriched by travels. He journeyed to Venice around 1582, where he immersed himself in the works of Titian and Paolo Veronese, absorbing their rich color palettes and dynamic compositions. A subsequent trip to Parma allowed him to study the masterpieces of Correggio, whose soft modeling and graceful figures left a lasting impression. These experiences broadened his artistic horizons and solidified his commitment to a style grounded in observation yet elevated by classical ideals.

The Carracci Reform and the Accademia degli Incamminati

The late 16th century in Italy saw Mannerism, a style characterized by artificiality, elongated figures, and complex allegories, becoming increasingly formulaic. Reacting against this trend, Agostino, Annibale, and Ludovico Carracci sought to revitalize painting. Their reform was not a rejection of the past but a synthesis of its strengths: the anatomical power of Michelangelo, the harmonious compositions of Raphael, the vibrant color of Titian and Veronese, and the tender grace of Correggio, all fused with a renewed emphasis on drawing directly from nature.

To propagate their ideas and train a new generation of artists, the Carracci founded an academy in Bologna around 1582-1585. Initially known perhaps as the Accademia dei Desiderosi (Academy of the Desirous), it later became famous as the Accademia degli Incamminati (Academy of Those on the Right Path, or Academy of the Progressives). This was not a formal institution in the modern sense but rather a workshop and intellectual hub. Here, the Carracci emphasized life drawing, particularly from nude models, anatomical studies, perspective, and the critical analysis of Renaissance masterpieces. They encouraged discussion and debate, fostering an environment distinct from the more rigid master-apprentice system prevalent elsewhere. The Academy attracted numerous talented students and became the crucible for the development of the influential Bolognese School of painting, a cornerstone of the Italian Baroque.

Collaborative Fresco Projects in Bologna

The Carracci family often worked collaboratively, particularly on large-scale fresco decorations in their native Bologna. These early joint projects helped establish their reputation and demonstrate their reformist principles in practice. One of the earliest significant commissions was the fresco cycle depicting the Stories of Jason and Medea (c. 1583-1584) in the Palazzo Fava. Here, the three artists worked side-by-side, developing a cohesive style that blended Ludovico's dramatic intensity, Annibale's burgeoning naturalism, and Agostino's learned classicism and refined draughtsmanship.

Another major collaborative project was the decoration of the Palazzo Magnani (c. 1590-1592) with frescoes illustrating the Founding of Rome. These works showed a growing confidence and mastery, further solidifying the Carracci's position as leading artists in Bologna. While distinguishing the individual hands in these collective works can be challenging, Agostino's contributions are often associated with more classically inspired figures and compositions, reflecting his intellectual inclinations and deep study of antiquity and the High Renaissance. These Bolognese fresco cycles were crucial in demonstrating the viability of their new, naturalistic yet classically informed style on a monumental scale.

Agostino Carracci: Master Printmaker

While Agostino was a capable painter, his greatest contemporary fame and perhaps his most enduring legacy lie in his work as a printmaker. He was exceptionally skilled in both engraving and etching, mastering the technical intricacies of both media. His early training as a goldsmith provided a strong foundation for the precise work required in engraving. He became one of the most important reproductive printmakers of his era, translating the paintings of High Renaissance and contemporary masters into black and white with remarkable fidelity and artistic sensitivity.

His prints after works by artists such as Titian, Veronese, Correggio, Tintoretto, and Federico Barocci were instrumental in disseminating knowledge of their compositions throughout Europe. These were not mere copies; Agostino interpreted the originals, capturing their spirit and often adding his own stylistic nuances. His prints were highly sought after by collectors and artists alike. Notably, the great Dutch master Rembrandt van Rijn was known to admire and collect Agostino's prints, recognizing their technical brilliance and artistic merit.

Agostino also produced original prints, including portraits and mythological and allegorical subjects. Among his most discussed original works is the series known as the Lascivie, small erotic prints depicting mythological lovers. While potentially created partly for commercial reasons to satisfy a market demand, they showcase his skill in rendering the human form and his engagement with classical themes, albeit in a controversial manner for the time. His printmaking technique, sometimes referred to as the "grand style" for its broad, confident lines and effective modeling, significantly influenced the development of engraving and etching as independent art forms. His dispute with Barocci over the quality of prints made after Barocci's paintings highlights the professional rivalries and high standards prevalent in the printmaking world of the era.

Rome and the Farnese Gallery Ceiling

Around 1595, Annibale Carracci was summoned to Rome by the powerful Cardinal Odoardo Farnese to undertake the decoration of the Farnese Palace, one of the most prestigious commissions of the time. Agostino joined his brother in Rome around 1597 to assist on the monumental project, particularly the ceiling frescoes of the Farnese Gallery depicting The Loves of the Gods (1597-1601). This cycle is considered Annibale's masterpiece and a foundational work of Baroque ceiling painting.

Agostino's precise role in the Farnese Gallery is debated by art historians, but he is generally credited with contributing specific sections, possibly including the mythological scenes featuring Cephalus and Aurora and the Triumph of Galatea. His more theoretical and learned approach may have also influenced the complex iconographic program of the ceiling. However, contemporary accounts suggest friction developed between the brothers. Annibale, focused intensely on the execution of the vast project, reportedly grew impatient with Agostino's more deliberate pace and perhaps his perceived pedantry. This tension eventually led to Agostino leaving Rome around 1600, before the gallery was fully completed. Despite these difficulties, his involvement links him to one of the most influential decorative schemes in Western art.

Final Years in Parma

After departing Rome, Agostino sought patronage elsewhere. He found a significant opportunity in Parma, receiving a commission from Duke Ranuccio I Farnese (who was related to Cardinal Odoardo in Rome) to decorate the Palazzo del Giardino. This independent commission represented a chance for Agostino to showcase his talents on a grand scale, free from collaboration with his brother. He began work on a series of frescoes with mythological themes, intended for the vault of a large hall.

His work in Parma demonstrated his mature style, combining his Venetian-inspired use of color with his Roman experience and Bolognese naturalism. He planned an elaborate scheme celebrating the Duke and the Farnese lineage through classical allegory. Unfortunately, this major project remained unfinished. Agostino Carracci died suddenly in Parma on February 23, 1602, at the relatively young age of 44. His premature death cut short his career just as he was undertaking one of his most ambitious independent commissions.

Major Paintings and Artistic Style

Although often overshadowed by Annibale as a painter, Agostino produced several significant easel paintings that reveal his distinct artistic personality. His most celebrated painting is The Last Communion of St. Jerome (c. 1592), now housed in the Pinacoteca Nazionale di Bologna. This altarpiece, painted for the church of San Girolamo alla Certosa, is renowned for its emotional intensity, clear narrative, compositional clarity, and rich, Venetian-influenced color. It depicts the dying saint receiving the Eucharist with profound piety, surrounded by grieving attendants. The work's dramatic realism and psychological depth made it highly influential, serving as a model for later Baroque artists, including Domenichino, who painted his own famous version of the subject.

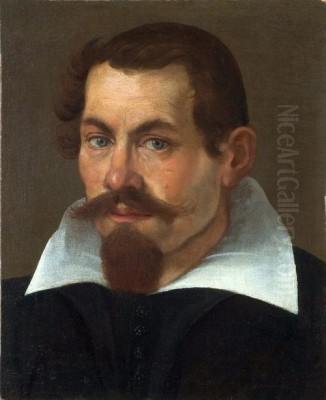

Agostino also excelled at portraiture. His Portrait of Giovanni Gabrielli, called Il Sivello (c. 1599), demonstrates his ability to capture a sitter's likeness and personality with sensitivity and directness. The Triple Portrait (Arrigo the Hairy, Pietro the Fool, and Amon the Dwarf) (c. 1598-1600) is a fascinating genre-like work showcasing his keen observation of human physiognomy and character, depicting members of the court renowned for their unusual appearances.

Overall, Agostino's painting style represents a thoughtful synthesis. He blended the naturalism championed by the Carracci reform with a strong sense of classical order and idealized beauty derived from his study of Raphael and antiquity. His color palette often reflects his Venetian studies, while his compositions are typically well-structured and legible. Compared to Annibale's more robust dynamism or Ludovico's sometimes darker emotionalism, Agostino's work often possesses a more refined, intellectual, and sometimes lyrical quality.

Agostino's Intellectual Role and Contrast with Caravaggio

Within the Carracci trio, Agostino was often regarded as the most intellectual and theoretically inclined. His broad knowledge of literature, mythology, and art history informed his work and likely played a significant role in shaping the curriculum and philosophical discussions at the Accademia degli Incamminati. He embodied the ideal of the learned painter, capable of engaging with complex iconographic programs and classical sources.

His approach provides a fascinating counterpoint to that of another giant of the era, Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio. Both the Carracci and Caravaggio rejected Mannerism and championed a return to naturalism. However, their interpretations differed significantly. Caravaggio pursued a radical, often gritty realism, using dramatic chiaroscuro (contrasts of light and dark) and depicting religious scenes with figures drawn from contemporary street life. Agostino and his family, while committed to observation, generally tempered their naturalism with classical idealism, seeking a balance between reality and decorum. Agostino's style, particularly, emphasized clarity, grace, and idealized forms, standing in contrast to Caravaggio's raw immediacy. Together, these two strands – the classicizing Baroque of the Carracci and the dramatic realism of Caravaggio – would define the major directions of Italian painting in the 17th century.

Legacy and Influence

Agostino Carracci's influence extended through several channels. His role as a co-founder and teacher at the Accademia degli Incamminati was crucial in shaping the next generation of Bolognese artists, including figures like Domenichino, Guido Reni, Francesco Albani, and Guercino, who would dominate Italian painting in the first half of the 17th century. While these artists also studied directly with Annibale and Ludovico, Agostino's intellectual contributions and teaching were integral to the Academy's success and the formation of the Bolognese School.

His prints had an even wider reach, circulating throughout Europe and influencing artists far beyond Italy. They disseminated the compositions of Italian masters and promoted the Carracci's own artistic ideals. The admiration of artists like Rembrandt attests to the high regard in which his graphic work was held.

As a painter, while his output was smaller than Annibale's and his career cut short, works like The Last Communion of St. Jerome stand as masterpieces of early Baroque art, demonstrating the power and potential of the Carracci reform. He played an indispensable part in the collective effort that moved Italian art away from the perceived excesses of Mannerism towards a new style grounded in nature, classical principles, and emotional directness.

Conclusion: A Multifaceted Contributor to the Baroque

Agostino Carracci's career, though relatively brief, was marked by significant achievements across multiple artistic fields. As a painter, he contributed to major collaborative projects and produced individual masterpieces characterized by their blend of naturalism, classicism, and emotional depth. As a printmaker, he was among the most skilled and influential of his time, playing a vital role in the dissemination of artistic ideas. As a teacher and theorist, he was instrumental in founding the Accademia degli Incamminati and shaping the principles of the Bolognese School, which became a dominant force in Italian Baroque art. While often viewed in relation to his more famous brother Annibale, Agostino Carracci was a formidable artist and intellect in his own right, whose contributions were essential to the artistic revolution initiated by his family and whose legacy resonated through the subsequent development of European art.