Francesco Furini stands as a distinctive and somewhat enigmatic figure within the vibrant tapestry of Italian Baroque art. Active primarily in Florence during the first half of the seventeenth century (Seicento), Furini carved a unique niche for himself, blending the refined elegance inherited from the Florentine tradition with the dramatic intensity and novel approaches emerging from Rome and elsewhere. Known particularly for his mastery of sfumato – the soft, hazy transition between colours and tones – and his often sensuous depictions of the female form, Furini's work offers a fascinating glimpse into the artistic currents and cultural complexities of his time. Though perhaps less universally recognized today than some of his Roman or Bolognese contemporaries, his artistic contributions were significant, influencing his peers and successors in Tuscany and leaving behind a body of work celebrated for its delicate beauty and psychological nuance.

Early Life and Florentine Foundations

Francesco Furini was born in Florence, likely around 1603 or 1604, into a family of modest means, though one with artistic inclinations. His initial artistic instruction came from his father, Filippo Furini, himself a painter of portraits, sometimes referred to as 'Pippo Sciamerone'. This early familial grounding in art provided the young Francesco with fundamental skills, setting the stage for more formal training. Florence, at this time, still basked in the long shadow of its Renaissance glories, with the legacies of giants like Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael deeply ingrained in its artistic identity. However, the city was also navigating the stylistic shifts of the late Mannerist period and the burgeoning Baroque.

Seeking to advance his skills, Furini entered the bustling workshop of Matteo Rosselli, one of the leading painters in Florence at the time. Rosselli's studio was a significant training ground, fostering the talents of many artists who would shape the Florentine Seicento, including Lorenzo Lippi and Baldassare Franceschini, known as Il Volterrano. Under Rosselli, Furini would have honed his skills in drawing (disegno), a cornerstone of Florentine artistic practice, and absorbed the somewhat conservative, yet elegant, style favoured by his master.

Further shaping his early development were the influences of other prominent Florentine artists. Domenico Passignano, who had spent time in Venice and Rome, brought a richer colour palette and more dynamic compositions back to Florence. Giovanni Biliverti, another significant figure and himself a student of Lodovico Cigoli, was known for his refined technique and often dramatic religious scenes. Exposure to these artists broadened Furini's artistic horizons beyond the immediate confines of Rosselli's workshop, introducing him to different approaches to colour, light, and composition prevalent in early seventeenth-century Florence.

The Roman Experience and Stylistic Evolution

A pivotal moment in Furini's artistic journey occurred around 1619 when he traveled to Rome. The Eternal City was then the undisputed epicentre of the art world, pulsating with innovation and artistic rivalry. Here, Furini encountered firsthand the revolutionary naturalism and dramatic chiaroscuro of Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, whose impact was still profoundly felt despite his death nearly a decade earlier. The work of Caravaggio and his followers (the Caravaggisti) offered a stark contrast to the more idealized and restrained Florentine manner. The intense light and shadow, the unvarnished realism, and the psychological immediacy of Caravaggism left an indelible mark on the young Furini.

Beyond Caravaggism, Rome offered Furini the invaluable opportunity to study the masterpieces of classical antiquity. The city's wealth of ancient Greek and Roman sculpture provided a deep wellspring of inspiration, particularly for depicting the human form with anatomical accuracy and idealized grace. This engagement with classical models would become a recurring feature in Furini's work, informing the poses, proportions, and serene beauty of his figures, especially his renowned nudes. He likely also studied the works of High Renaissance masters like Raphael, whose clarity of form and harmonious compositions remained influential benchmarks. Furthermore, exposure to the Bolognese school, perhaps through the works of Guido Reni who was active in Rome, may have reinforced an appreciation for classical grace and refined sentiment.

This Roman sojourn was transformative. While Furini never fully abandoned his Florentine roots in precise drawing and elegant composition, his style gained a new depth and complexity. He began to integrate the dramatic potential of chiaroscuro, though typically softened and diffused compared to the starkness of Caravaggio. His engagement with classical sculpture refined his figure drawing, lending his subjects a palpable, yet idealized, presence. The Roman experience equipped him with a broader artistic vocabulary, allowing him to synthesize diverse influences into a distinctive personal style upon his return to Florence.

Return to Florence: Maturity and Signature Style

Upon returning to Florence, likely in the early 1620s, Francesco Furini began to establish himself as an independent master. He quickly gained recognition and commissions, developing the signature style for which he is best known. Central to this style was his sophisticated use of sfumato, a technique famously employed by Leonardo da Vinci. Furini adapted this technique to create soft, hazy contours and seamless transitions between light and shadow, imbuing his figures, particularly their flesh, with a delicate, almost porcelain-like quality. This contrasted with the harder outlines often favoured in traditional Florentine disegno.

His palette typically consisted of soft, often muted colours, favouring subtle harmonies over bold contrasts. Flesh tones were rendered with exceptional sensitivity, capturing a sense of warmth and softness that lent his figures a remarkable lifelike quality, albeit an idealized one. The interplay of light and shadow in his mature works is nuanced; while clearly influenced by Roman chiaroscuro, Furini's lighting is generally less dramatic and more diffused, creating an atmosphere of gentle intimacy or quiet contemplation rather than stark theatricality.

During this period, Furini became part of the vibrant Florentine artistic community. He maintained connections with fellow artists, including his former colleagues from Rosselli's workshop like Lorenzo Lippi. He also formed a friendship with the painter Giovanni da San Giovanni (Giovanni Mannozzi), a highly regarded fresco painter known for his lively and sometimes eccentric works, who also acted as a patron or supporter. Furini's growing reputation also brought him into contact with influential figures beyond the art world, reportedly including the great scientist Galileo Galilei, reflecting the intellectual ferment of seventeenth-century Florence.

Thematic Focus: Mythology, Religion, and the Nude

Furini's subject matter drew heavily from biblical narratives and classical mythology, common themes during the Baroque era. However, he approached these subjects with his characteristic sensibility, often focusing on moments of intimacy, vulnerability, or quiet emotion. His religious paintings, such as depictions of the Penitent Magdalene or female saints like Saint Agatha, often combined spiritual intensity with a subtle sensuality, a hallmark of his style that sometimes drew criticism. Works like Saint John the Evangelist showcase his ability to render figures with both physical presence and contemplative depth.

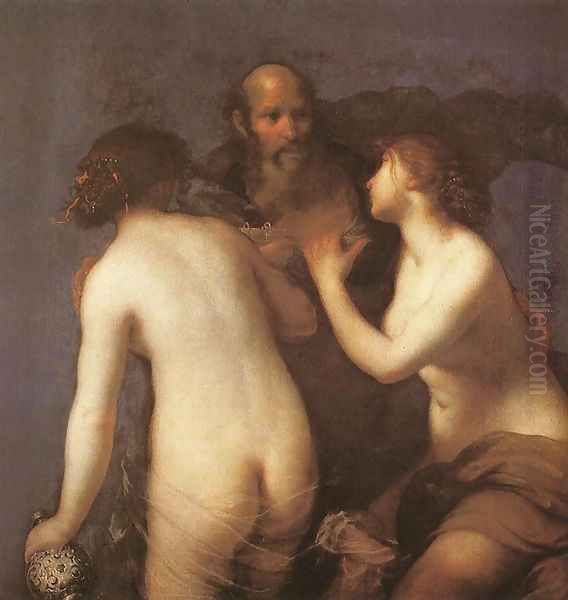

It was, however, his treatment of mythological themes, particularly those involving the female nude, that became his most celebrated and sometimes controversial specialty. Paintings like Hylas and the Nymphs, Andromeda, Artemisia preparing to drink the ashes of her husband, and Cephalus and Aurora allowed Furini to explore the beauty of the human form, often drawing inspiration from classical sculpture for poses and idealized proportions. His nudes are rarely overtly erotic in the manner of some Venetian Renaissance painters like Titian; instead, they possess a delicate, almost ethereal sensuality, enhanced by the soft focus of his sfumato technique.

The ambiguity inherent in Furini's nudes – simultaneously idealized and sensual, innocent yet alluring – became a defining feature of his art. This delicate balance reflected the complex cultural attitudes of the Counter-Reformation era, which simultaneously encouraged emotionally engaging religious art while remaining wary of overt sensuality. Furini navigated this tension skillfully, creating images that were admired for their beauty and technical mastery, even as their perceived sensuousness occasionally provoked moral commentary. His deep understanding of classical art allowed him to imbue these mythological scenes with a sense of timeless grace and artistic authority.

Mastery of the Female Form

The depiction of the female nude is arguably the most distinctive aspect of Francesco Furini's oeuvre. He developed an extraordinary ability to render flesh with a soft, luminous quality, using his signature sfumato to dissolve sharp outlines and create smooth, subtle modulations of tone. This technique lent his figures a palpable softness and warmth, making them appear almost to emerge gently from the surrounding shadows. The skin tones are often pearlescent, enhancing the idealized beauty of his subjects.

His approach differed significantly from the more robust or overtly sensual nudes found elsewhere in Italian art. Compared to the Venetian tradition exemplified by Titian or the more muscular classicism sometimes seen in Roman Baroque figures, Furini's nudes are characterized by their delicacy, smooth finish, and often introspective or melancholic expressions. The poses frequently echo classical statuary, suggesting his careful study of antiquity, but they are infused with a lifelike tenderness through his handling of paint.

This focus on the idealized female form, rendered with such technical finesse, secured Furini's reputation among patrons and collectors. Works featuring solitary female figures, often drawn from mythology or allegory, became highly sought after. Examples include his various depictions of penitent saints or mythological heroines, where the narrative context often provided a justification for the nudity while allowing the artist to showcase his skill. The psychological dimension of these figures – their frequent air of vulnerability or quiet contemplation – adds another layer of complexity, inviting viewers to engage with the image on both an aesthetic and emotional level.

Major Commissions and Medici Patronage

Furini's talent did not go unnoticed by Florence's most important patrons, the Medici Grand Dukes. During the 1630s, he received prestigious commissions to contribute to the decoration of the Palazzo Pitti, the grand ducal residence. Working alongside other leading Florentine artists, Furini painted frescoes in the Sala degli Argenti (Silver Room) on the ground floor. His contributions included two large lunettes depicting allegorical scenes related to the Medici family: Lorenzo de' Medici the Magnificent and the Platonic Academy and the Allegory of the Death of Lorenzo the Magnificent.

These frescoes demonstrate Furini's ability to work on a large scale and adapt his style to the demands of monumental decoration. While retaining his characteristic softness in the rendering of figures, the compositions are necessarily more complex and populated than many of his easel paintings. The Platonic Academy scene, celebrating the intellectual and cultural patronage of Lorenzo the Magnificent, showcases Furini's skill in arranging multiple figures in a harmonious composition, imbued with a sense of learned dignity appropriate to the subject. These commissions solidified Furini's status as one of the leading painters in Florence under Grand Duke Ferdinand II de' Medici.

Beyond the Medici, Furini enjoyed patronage from other noble families and collectors in Florence and beyond. His easel paintings, particularly his mythological scenes and depictions of female saints, were popular for private collections. The demand for his work indicates his success in catering to the tastes of the Florentine elite, who appreciated his refined technique, elegant compositions, and the subtle sensuality that characterized his most famous works. His reputation even extended beyond Tuscany, with works reportedly finding their way into collections in Spain and Austria.

The Priesthood and Later Years

In a surprising turn, around 1633, Francesco Furini took holy orders and became a priest. He was subsequently appointed as the parish priest of Sant'Ansano in Mugello, a rural area outside Florence. The reasons for this decision remain somewhat speculative. Some contemporary biographers suggested it was a response to criticism directed at the perceived licentiousness of his nude paintings, a way to distance himself from potential controversy and demonstrate his piety. Others might argue it stemmed from genuine religious conviction, not uncommon in the fervent atmosphere of the Counter-Reformation.

Whatever the motivation, his ordination did not mark the end of his artistic career. Furini continued to paint, perhaps focusing more intently on religious subjects, although mythological themes did not disappear entirely from his output. Works from this later period, such as Lot and his Daughters (dated 1645-46), demonstrate a continuity of his signature style, with its soft sfumato and delicate rendering of figures, even when tackling potentially challenging biblical narratives.

His life as a priest-painter adds a fascinating layer to his biography. It highlights the potential tension between artistic expression, particularly the depiction of the human body, and religious devotion in the seventeenth century. Furini seems to have navigated this duality, continuing to produce works admired for their aesthetic qualities while fulfilling his clerical duties. He remained connected to the Florentine art world and continued to receive commissions until his relatively early death in Florence in 1646.

Workshop, Influence, and Legacy

Francesco Furini maintained a workshop and trained pupils, ensuring the transmission of his style and techniques. His most notable student was Simone Pignoni (1611-1698), whose own work often closely resembles Furini's, particularly in the treatment of female nudes and the use of soft, hazy effects. Pignoni carried Furini's stylistic tendencies into the later seventeenth century, though often with a more overtly sensual or dramatic flair. The similarity between their styles has occasionally led to difficulties in attribution, with some works historically moving between the two artists. Another documented pupil was Giovanni Battista Galestruzzi, who became known more as an etcher and painter.

Furini's influence extended beyond his direct pupils, contributing to the specific character of Florentine Baroque painting. His emphasis on sfumato, refined finish, and elegant figure types offered an alternative to the more robust or dramatic styles prevalent elsewhere in Italy. He, along with contemporaries like Carlo Dolci, known for his highly polished and intensely pious small-scale religious works, represented a particularly Florentine sensibility that valued technical refinement, grace, and a certain emotional restraint, even when depicting charged subjects.

While highly regarded in his time and recognized as a key figure in the Florentine Seicento, Furini's fame perhaps suffered in subsequent centuries compared to the giants of the Roman or Bolognese schools like Caravaggio, Annibale Carracci, or Guido Reni. His style, with its emphasis on subtlety and softness, may have seemed less impactful than the high drama or vigorous naturalism often associated with the mainstream Baroque. However, modern art history has increasingly recognized his unique contribution, appreciating the technical mastery, psychological depth, and distinctive beauty of his work. Exhibitions and scholarly research continue to shed light on his career and secure his place as a significant master of the Italian Baroque.

Conclusion: A Distinctive Florentine Voice

Francesco Furini remains a compelling figure in seventeenth-century Italian art. Emerging from the rich artistic soil of Florence, he absorbed the lessons of his predecessors and contemporaries, engaged deeply with the innovations emanating from Rome, and forged a highly personal style. His mastery of sfumato allowed him to create images of extraordinary delicacy and atmospheric subtlety. His sensitive, often sensuous, depictions of the human form, particularly the female nude drawn from mythology and religion, represent a unique blend of Florentine elegance, classical idealization, and Baroque sensibility.

His decision to enter the priesthood adds a layer of intrigue to his life, highlighting the complex interplay between art, sensuality, and piety in his era. Despite periods of relative obscurity, Furini's art continues to captivate viewers with its refined beauty, technical brilliance, and quiet emotional resonance. He stands as a testament to the enduring vitality and distinct character of the Florentine school during the Baroque period, a master whose soft focus revealed profound depths of artistry and feeling. His work offers a nuanced counterpoint to the more forceful expressions of the Baroque, reminding us of the diverse and sophisticated artistic landscape of Seicento Italy.