Albert Anker stands as one of Switzerland's most cherished and significant artists of the 19th century. Often affectionately dubbed the "National Painter," his work provides an intimate and enduring window into the everyday lives of ordinary Swiss people, particularly those in rural communities. Born in a period of significant social and cultural change, Anker developed a distinctive style rooted in Realism, yet imbued with a quiet dignity and warmth that continues to resonate with audiences today. His meticulous attention to detail, combined with a deep empathy for his subjects, cemented his place not only in Swiss art history but also in the cultural identity of the nation itself.

Early Life and Formative Years

Samuel Albert Anker was born on April 1, 1831, in the village of Ins (Annet in French) in the Bernese Seeland region of Switzerland. This area, situated at the confluence of French and German-speaking Switzerland, exposed the young Anker to a bilingual and bicultural environment from an early age, an influence that would subtly permeate his life and work. He was the son of Samuel Anker, a veterinarian, and Marianne Elisabeth Anker (née Gatschet). His upbringing, while not one of artistic immersion initially, provided him with a close connection to the rhythms and realities of rural life that would later become the cornerstone of his art.

A spark of artistic inclination ignited early. According to anecdotes, at the age of 11, a visit to an exhibition featuring paintings reportedly captivated him, planting the seeds for a future in art. However, his path was not immediately set towards painting. Tragedy struck the family when Albert was 16, with the deaths of his mother and a brother, events that undoubtedly left a profound mark on the young man. Despite his burgeoning interest in art, familial expectations and the practicalities of the time initially steered him towards a more conventional career path.

Education and the Call of Art

Anker's formal education began locally, but his artistic talents were nurtured early on. Between 1845 and 1848, while attending school in Neuchâtel, he received his first formal drawing lessons from Louis Wallinger. This early instruction provided a foundational basis for his technical skills. Following his secondary education, which included studies at the Gymnasium Kirchenfeld in Bern where he obtained his Matura (graduation certificate) in 1851, Anker bowed to his father's wishes and began studying theology.

He commenced his theological studies first at the University of Bern in 1851 before moving to Germany to continue at the University of Halle. Germany, particularly Halle with its rich cultural environment and art collections, proved to be a turning point. The exposure to art intensified his passion, creating a conflict between his prescribed path and his true calling. The desire to paint became overwhelming, leading to a crucial decision.

In 1854, Anker made the definitive choice to dedicate his life to art. He managed to persuade his father, who had initially envisioned a clerical career for his son, to support his artistic ambitions. This marked the end of his theological pursuits and the beginning of his journey as a professional artist. With his father's blessing, Anker set his sights on Paris, the undisputed center of the art world in the mid-19th century.

Parisian Training and Artistic Development

Arriving in Paris in 1855, Anker immersed himself in the vibrant and competitive artistic environment. He sought out the best training available, enrolling in the studio of the Swiss painter Charles Gleyre. Gleyre, himself a respected artist, ran a prominent teaching studio known for its relatively liberal atmosphere compared to the strict academicism of the official École des Beaux-Arts, although Gleyre himself maintained classical principles. This studio became a melting pot for aspiring artists from various backgrounds.

Crucially, Gleyre's studio was where Anker encountered several artists who would soon become leading figures of Impressionism. Among his fellow students were Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Claude Monet, Alfred Sisley, and Frédéric Bazille. While Anker's own artistic path would diverge significantly from the Impressionists' focus on capturing fleeting moments of light and color, the interactions and shared learning environment within Gleyre's studio undoubtedly exposed him to emerging ideas and fostered a spirit of artistic exploration. He absorbed the rigorous training in drawing and composition offered by Gleyre, honing the technical precision that would become a hallmark of his work.

Alongside his studies with Gleyre, Anker also attended classes at the École Impériale et Spéciale des Beaux-Arts (the French National School of Fine Arts), likely focusing on essential skills like anatomical drawing. He was a diligent student, dedicating time to studying the Old Masters in the Louvre. He particularly admired and copied works by Renaissance masters such as Correggio and Tiziano Vecelli (Titian), absorbing lessons in composition, color, and the rendering of form and texture. This classical grounding provided a solid counterpoint to the contemporary influences swirling around him in Paris. His time in Paris was not solely about formal training; it was also about absorbing the city's artistic energy and participating in its exhibition culture. He began exhibiting his work, notably at the prestigious Paris Salon.

The Emergence of a Realistic Vision

Albert Anker's artistic style is firmly rooted in Realism, a movement that gained prominence in France around the mid-19th century, championed by artists like Gustave Courbet and Jean-François Millet. Realism sought to depict contemporary subjects and situations with truth and accuracy, rejecting the idealized or exotic themes of Neoclassicism and Romanticism. Anker embraced this ethos, turning his attention to the world he knew best: the everyday life of rural Switzerland.

His Realism, however, possessed a unique character. Unlike the often stark or socially critical Realism of Courbet, Anker's work generally presented a more harmonious and ordered view of society. He focused on the quiet dignity of labor, the importance of family and community, and the innocence of childhood. His paintings rarely depicted overt poverty, conflict, or social unrest. Instead, they often conveyed a sense of stability, diligence, and quiet contentment, reflecting perhaps a specific vision of Swiss national identity rooted in traditional values and rural life.

Anker's technique was characterized by meticulous detail, careful composition, and a sensitive handling of light and color. He often worked from detailed preliminary drawings, sometimes using charcoal or watercolor, before executing the final oil painting. His brushwork is generally smooth and controlled, allowing for a high degree of finish and clarity. He possessed a remarkable ability to render textures – the roughness of woolen clothing, the smoothness of polished wood, the transparency of glass, the softness of a child's skin – contributing significantly to the convincing realism of his scenes. Light in his paintings is often calm and diffused, typically illuminating indoor scenes from a window or casting a gentle glow on outdoor settings, enhancing the peaceful and intimate atmosphere.

Chronicler of Swiss Rural Life

The heart of Anker's oeuvre lies in his depiction of 19th-century Swiss village life. He returned frequently to his hometown of Ins, where he maintained a studio in the attic of his house. This connection provided him with an endless source of authentic subjects and models, often drawn from his own family and neighbors. His paintings document a way of life that was undergoing gradual change due to industrialization and modernization, capturing traditions, domestic interiors, and social interactions with ethnographic precision, albeit through an artistic lens.

Children are perhaps the most frequent and beloved subjects in Anker's work. He portrayed them with remarkable sensitivity and understanding, capturing their concentration during lessons, their absorption in play, their quiet moments of contemplation, or their interactions with family members. Works like The Village School of 1848 (painted 1896) or Girl Peeling Potatoes (1886) showcase his ability to depict children naturally, without sentimentality but with genuine affection and respect. These scenes often subtly underscore the importance Anker placed on education and diligence.

His famous painting Reading Aloud to Grandfather (Die Andacht des Grossvaters, 1893) is a quintessential Anker work. It depicts a young girl intently reading the Bible to her elderly, attentive grandfather in a simple, rustic interior. The scene is imbued with a sense of intergenerational connection, piety, and the value of literacy. It exemplifies Anker's ability to elevate a simple domestic moment into a poignant reflection on family, tradition, and faith. The careful rendering of the figures, the detailed interior, and the warm, focused light all contribute to the painting's enduring appeal.

Domesticity, Portraits, and Still Lifes

Beyond scenes of childhood and education, Anker explored various facets of domestic and community life. He painted women engaged in traditional activities like knitting (Old Woman Knitting, c. 1880s), families gathered for meals (The Midday Meal, 1872), and individuals performing daily tasks. These works often emphasize values of hard work, domestic harmony, and community cohesion. His depictions are never condescending; they portray the subjects with respect and highlight the quiet importance of their everyday routines.

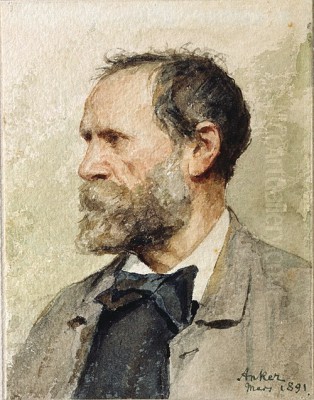

Anker was also a skilled portraitist. While he painted commissioned portraits, many of his most compelling likenesses are of his family members and local villagers. His portraits are characterized by their psychological insight and straightforward presentation. He often captured his subjects in thoughtful or introspective poses, revealing aspects of their personality through subtle expressions and gestures. His own children frequently served as models, appearing in numerous genre scenes and individual portraits, such as depictions of his daughter Louise Anker.

Furthermore, Anker demonstrated considerable talent in still life painting. Often overlooked in favor of his genre scenes, his still lifes are remarkable for their technical precision and compositional clarity. He typically depicted simple arrangements of everyday objects – fruit, vegetables, pottery, glassware, books – rendered with an almost photographic accuracy. These works showcase his mastery of texture, light, and form, and often carry a quiet, contemplative mood. They reveal his deep appreciation for the beauty found in ordinary objects and his dedication to careful observation.

Diversification: Ceramics and Illustration

Anker's artistic activities extended beyond oil painting and watercolor. To supplement his income, particularly during periods when supporting his growing family was a concern, he engaged in decorative work. Notably, between 1866 and 1892, he created designs for faience (tin-glazed earthenware) produced by the Alsatian manufacturer Théodore Deck. Anker produced over 500 designs for Deck, often featuring motifs drawn from his familiar repertoire of rural life, children, and historical or allegorical themes. This collaboration highlights his versatility and his engagement with the applied arts.

He also worked as an illustrator, contributing drawings for books and publications. This aspect of his work further disseminated his characteristic style and subjects to a wider audience, reinforcing his popular image as a chronicler of Swiss life. His clear, narrative style lent itself well to illustration, complementing texts with visual interpretations that were both informative and engaging.

Career, Recognition, and Social Engagement

Anker achieved considerable success and recognition during his lifetime, both within Switzerland and internationally. He regularly exhibited his work at the Paris Salon, a crucial venue for establishing an artist's reputation. His participation was often met with positive reception, and in 1866, he was awarded a gold medal at the Salon for his paintings Sleeping Girl in the Forest and Writing Lesson. He also exhibited frequently in Switzerland, becoming a leading figure in the national art scene. His popularity grew steadily, and his works were sought after by collectors and institutions. He secured a contract with the prominent Parisian art dealer Alphonse Goupil, which helped promote his work internationally.

His contributions were formally acknowledged through various honors. He was made a Chevalier (Knight) of the French Legion of Honour in 1878, a significant international distinction. In 1900, the University of Bern awarded him an honorary doctorate in recognition of his artistic achievements and cultural significance. His status as Switzerland's "National Painter" solidified during his lifetime, reflecting the deep connection the Swiss public felt with his depictions of their land and people. His images became iconic, even appearing on Swiss postage stamps, further cementing his place in the national consciousness.

Beyond his artistic endeavors, Anker was actively engaged in the civic life of his community and country. From 1870 to 1874, he served as a member of the Grand Council of Bern (the cantonal parliament). During his tenure, he was a strong advocate for the establishment of the Bern Museum of Fine Arts (Kunstmuseum Bern), demonstrating his commitment to fostering cultural institutions in Switzerland. His political engagement also reflected his social concerns; he was known to support progressive causes, including the movement for co-education (educating boys and girls together), which gained traction in Switzerland in the 1870s. This interest in education is clearly mirrored in the frequent depiction of schools and reading in his paintings.

Later Life and Enduring Legacy

Anker spent his winters in Paris for many years but maintained his primary residence and studio in his family home in Ins. In 1890, he decided to cease his winter stays in Paris and settled permanently in Ins. His life took a difficult turn in September 1901 when he suffered a severe stroke, which tragically left his right hand permanently paralyzed. For a painter renowned for his meticulous technique, this was a devastating blow.

Despite this immense challenge, Anker did not abandon his art. Unable to undertake large-scale oil paintings requiring the same level of physical control, he adapted his practice. He learned to work more extensively with his left hand and focused primarily on watercolors, often creating smaller-scale works. Between 1901 and his death in 1910, he produced hundreds of watercolors, demonstrating remarkable resilience and an enduring creative spirit. These later works, while perhaps different in scale and medium, retain his characteristic sensitivity and observational skill.

Albert Anker passed away on July 16, 1910, in his beloved hometown of Ins, at the age of 79. His death was mourned throughout Switzerland, marking the loss of a national cultural icon. His legacy, however, was far from over. His studio in Ins, preserved much as he left it, became the heart of the Albert Anker Foundation and later the Albert Anker Centre, a museum dedicated to his life and work. It remains an important site for understanding his artistic process and his connection to the local community.

Anker's paintings continue to be immensely popular in Switzerland and are held in high regard internationally. Major retrospectives of his work draw large crowds, and his paintings command high prices at auction. His enduring appeal stems from several factors: the technical mastery of his art, the nostalgic charm of the rural world he depicted, the relatable human emotions he captured, and the sense of national identity his work evokes for many Swiss people. While some later critics occasionally found his vision perhaps too idyllic or lacking the overt social critique found in some other Realists like Courbet or Millet, his position as a masterful observer and sensitive chronicler of a specific time and place remains undisputed. He stands alongside other major Swiss artists like Ferdinand Hodler, though stylistically very different, as a key figure in the nation's art history. His interactions with contemporaries like Renoir, Monet, Sisley, Bazille, and Whistler during his formative years in Paris place him within the broader currents of 19th-century European art, even as he forged his own distinct path celebrating the life of his homeland.

Conclusion

Albert Anker's contribution to art extends beyond his beautiful and meticulously crafted paintings. He was a documenter of a disappearing way of life, a sensitive portraitist of childhood and old age, and a quiet advocate for education and community values. His training under figures like Louis Wallinger and Charles Gleyre, his engagement with the art world of Paris alongside future Impressionists, and his deep connection to his Swiss roots all shaped his unique artistic identity. Influenced by the realism of his time and the techniques of Old Masters like Correggio and Titian, he created a body of work that is both historically specific and universally resonant. As Switzerland's "National Painter," Albert Anker captured the heart of his nation, leaving behind a legacy of images that continue to speak of dignity, diligence, and the enduring beauty of everyday life.