Georgios Jakobides stands as one of the most prominent and beloved figures in the history of modern Greek art. His work, deeply rooted in the traditions of 19th-century European academic realism, particularly the Munich School, captured the hearts of the Greek public with its sentimental charm, technical mastery, and intimate portrayal of everyday life, especially the world of children. His career spanned a crucial period of artistic development in Greece, and his influence as both an artist and an educator left an indelible mark on subsequent generations.

A Biographical Sketch

Georgios Jakobides was born in 1853 in the village of Chidira on the island of Lesbos, then part of the Ottoman Empire. His early life was marked by a burgeoning interest in art, though formal training opportunities were scarce on the island. Recognizing his talent, his family supported his move to Smyrna (Izmir) for his initial education, and later, in 1870, to Athens. This move was pivotal, as it allowed him to enroll at the Athens School of Fine Arts, the premier institution for artistic training in Greece at the time.

At the Athens School of Fine Arts, Jakobides studied under influential figures of early modern Greek art, most notably Nikiforos Lytras, a leading proponent of the Munich School style in Greece. Lytras, himself trained in Munich, instilled in his students the principles of academic realism, emphasizing meticulous draftsmanship, careful observation, and a focus on genre scenes and portraiture. Jakobides excelled under this tutelage, demonstrating a natural aptitude for capturing human expression and form. His early works from this period already hinted at the thematic concerns and stylistic preferences that would define his mature career.

The Munich Years and Rise to Prominence

Upon graduating from the Athens School of Fine Arts in 1877, Jakobides, like many ambitious Greek artists of his generation, sought further training abroad. He chose Munich, the Bavarian capital that had become a major European art center, rivaling Paris in its academic rigor. He enrolled in the prestigious Academy of Fine Arts in Munich, where he studied under some of the leading masters of German academic painting. His professors included Ludwig von Löfftz, Wilhelm von Lindenschmit the Younger, and the renowned Gabriel von Max. Karl von Piloty, a towering figure in historical painting, also significantly influenced the academy's atmosphere, though Jakobides' focus remained more on genre.

During his seventeen years in Munich (1877-1900), Jakobides fully absorbed the tenets of the Munich School. This style was characterized by its detailed realism, often with a dark palette, dramatic lighting reminiscent of the Dutch Golden Age masters, and a preference for genre scenes, historical subjects, and portraiture. Jakobides thrived in this environment, quickly gaining recognition for his technical skill and the emotional resonance of his work. He established his own studio in Munich and began to exhibit regularly, earning critical acclaim and numerous awards. His paintings from this period, particularly those depicting children, became immensely popular, not only within Germany but also internationally.

The themes he explored in Munich often revolved around the innocence and charm of childhood, domestic life, and tender family moments. Works like "The First Steps" and "Grandfather's New Pipe" exemplify his ability to capture fleeting moments of human connection with warmth and sensitivity. His meticulous attention to detail, from the texture of fabrics to the subtle expressions on his subjects' faces, was a hallmark of his Munich period. He also undertook portrait commissions, demonstrating his versatility and skill in capturing the likeness and character of his sitters.

Return to Greece and Institutional Leadership

In 1900, Jakobides made the significant decision to return to Greece. His reputation had preceded him, and he was warmly welcomed back as one of the country's most accomplished artists. His return marked a new phase in his career, one where he would play a crucial role in shaping the artistic landscape of his homeland. He settled in Athens and continued to paint prolifically, though his subject matter began to incorporate more distinctly Greek elements, even as his style remained largely consistent with his Munich training.

A pivotal moment came in 1904 when Jakobides was appointed the first curator (director) of the newly established National Gallery of Greece in Athens. This prestigious position underscored his standing in the Greek art world. He dedicated himself to organizing and expanding the gallery's collection, laying the groundwork for what would become the nation's foremost repository of Greek art. His tenure at the National Gallery lasted until 1918, during which he also served as a professor at the Athens School of Fine Arts, the very institution where his artistic journey had begun.

As a professor, Jakobides influenced a new generation of Greek artists, passing on the academic principles he had mastered. While later artistic movements like Impressionism and modernism began to take hold in Greece, Jakobides remained a steadfast proponent of academic realism, a style that continued to resonate with a significant portion of the art-buying public and official institutions. He passed away in Athens in 1932, leaving behind a rich legacy as a painter, educator, and cultural figure.

Artistic Style and Thematic Focus

Jakobides' artistic style is firmly rooted in 19th-century academic realism, specifically the Munich School. Key characteristics of his work include:

Meticulous Realism: He possessed an exceptional ability to render figures, objects, and environments with a high degree of verisimilitude. Details of clothing, furniture, and human anatomy are depicted with precision.

Chiaroscuro and Lighting: Like many Munich School painters, Jakobides was a master of light and shadow (chiaroscuro). He often used a focused light source to illuminate his subjects against darker backgrounds, creating a sense of drama and depth, reminiscent of artists like Rembrandt. This technique was particularly effective in his interior scenes.

Sentimental Genre Scenes: His most popular and enduring works are his genre paintings, especially those featuring children. These scenes often depict tender, humorous, or poignant moments from everyday family life. He had a unique talent for capturing the natural expressions and gestures of children, avoiding artificiality and conveying genuine emotion.

Portraiture: Jakobides was also an accomplished portrait painter. His portraits are characterized by their psychological insight and faithful likeness, often commissioned by prominent members of Greek society. He painted portraits of royalty, politicians, and intellectuals, contributing to the visual record of his era.

Warm Palette and Emotional Tone: While the Munich School could sometimes tend towards a somber palette, Jakobides often infused his works with a warmth that enhanced their sentimental appeal. His paintings evoke feelings of nostalgia, affection, and domestic tranquility.

His thematic focus was predominantly on the human figure and human relationships. He rarely ventured into landscape painting for its own sake, though landscapes often formed the backdrops for his genre scenes. The world of children – their games, their interactions with grandparents, their small joys and sorrows – was a recurring and central theme. This focus distinguished him and contributed significantly to his widespread popularity.

Masterpieces and Signature Works

Several of Jakobides' paintings have become iconic in Greek art history, beloved for their charm and technical execution.

"Children's Concert" (c. 1894-1900): Perhaps his most famous work, this painting depicts a group of children engrossed in a playful, makeshift concert. The composition is dynamic, the children's expressions are lively and individual, and the interplay of light and shadow is masterfully handled. It epitomizes his ability to capture the innocent world of childhood with both realism and affection. This work, like many of his best, showcases a narrative quality, inviting the viewer to imagine the sounds and stories behind the scene.

"Grandfather's New Pipe" (or "The Favorite Grandson") (c. 1887): This heartwarming scene shows a young boy lighting his grandfather's pipe, their faces illuminated by the glow. The painting beautifully captures the affectionate bond between generations. The textures of the grandfather's aged skin and the boy's soft hair are rendered with exquisite detail. It’s a quintessential example of Jakobides' sentimental genre painting.

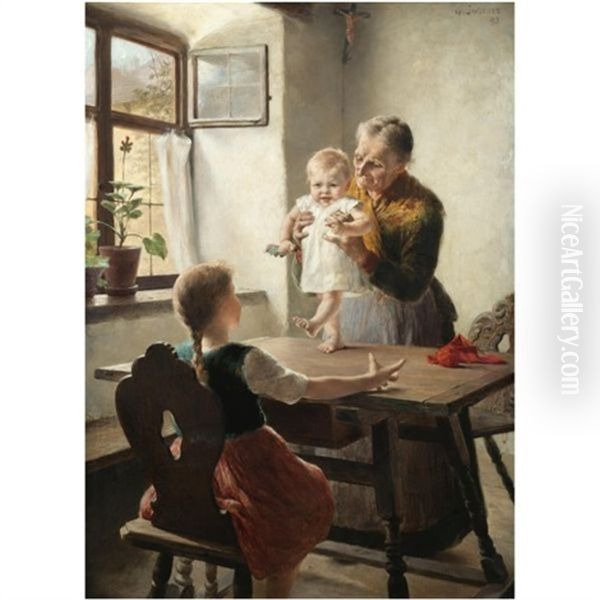

"The First Steps" (c. 1889): Another tender depiction of family life, this work shows a toddler taking tentative first steps, supported by an older sibling or caregiver, while a grandparent looks on with affection. The scene is filled with warmth and a sense of domestic harmony. The careful rendering of the interior and the figures’ attire grounds the emotional moment in a tangible reality.

"Bad Grandson" (or "The Naughty Grandchild") (c. 1884): This painting offers a more humorous take on intergenerational relationships, depicting a mischievous child who has likely caused some minor trouble, much to the exasperation or amusement of an elder. It showcases Jakobides' ability to convey subtle narratives and character through expression and gesture.

"The Scolding" (or "Grandmother's Admonition"): Similar in theme to "Bad Grandson," this work often portrays a child receiving a gentle reprimand from a grandmother. These scenes highlight Jakobides' keen observation of family dynamics and his sympathetic portrayal of both children and the elderly.

Beyond these well-known genre scenes, his portraits, such as those of Queen Olga or prominent Athenian citizens, demonstrate his skill in a more formal context, capturing not only the likeness but also the status and personality of his sitters.

Anecdotes and Personal Glimpses

While detailed personal anecdotes about Jakobides are not as widely circulated as those for some other artists, his personality can be inferred from his work and career. He was clearly a dedicated and disciplined artist, capable of producing a large body of highly finished work. His long and successful tenure in Munich suggests a professional who was adept at navigating the art world and meeting the demands of patrons and exhibitions.

His choice of subject matter, particularly the focus on children and family life, suggests a man with a gentle and empathetic nature. These were not themes chosen for shock value or avant-garde experimentation, but rather for their universal emotional appeal. The public's enthusiastic reception of these works indicates that he tapped into a widely shared appreciation for domesticity and innocence.

His commitment to the National Gallery of Greece as its first director also speaks to a sense of national pride and a desire to contribute to the cultural development of his country. He was entrusted with a significant responsibility, which he fulfilled diligently for over a decade. This role required not only artistic knowledge but also administrative skill and diplomacy.

One common observation is that Jakobides found a formula that resonated deeply with the bourgeois tastes of his time. His paintings were accessible, emotionally engaging, and technically impressive, making them highly desirable. While some later critics might have viewed his adherence to academicism as conservative, during his lifetime, this approach brought him considerable success and public adoration.

Mentors and Influences

Jakobides' artistic development was shaped by several key figures and artistic environments.

In Athens:

Nikiforos Lytras (1832-1904): His primary teacher at the Athens School of Fine Arts. Lytras was a foundational figure of the Munich School in Greece, and he imparted its principles of realism, genre painting, and solid draftsmanship to Jakobides. Lytras' own work often depicted scenes of Greek life with ethnographic detail and emotional depth, providing a model for Jakobides.

In Munich:

The Munich Academy of Fine Arts provided a rich environment with several influential professors:

Ludwig von Löfftz (1845-1910): Known for his genre and religious paintings, Löfftz emphasized meticulous technique and careful rendering of light and texture.

Wilhelm von Lindenschmit the Younger (1829-1895): A painter of historical scenes and genre subjects, he reinforced the academic traditions of strong composition and narrative clarity.

Gabriel von Max (1840-1915): A more eclectic artist known for his psychological portraits, allegorical, and even spiritualist themes. While Jakobides did not adopt Max's more unusual subject matter, he would have been exposed to Max's refined technique and interest in human psychology.

Karl von Piloty (1826-1886): Though Jakobides may not have studied directly under him for an extended period, Piloty was the dominant figure at the Munich Academy, famous for his large-scale historical paintings. His emphasis on dramatic composition, historical accuracy, and technical polish set the tone for the entire institution.

Beyond his direct teachers, Jakobides was undoubtedly influenced by the broader artistic currents of the Munich School, including the work of artists like Franz Defregger (1835-1921), known for his scenes of Tyrolean peasant life, and Wilhelm Leibl (1844-1900), a master of realism. The general atmosphere in Munich, with its respect for Old Masters like the Dutch realists, also played a role in shaping his aesthetic.

Legacy as an Educator

Upon his return to Greece, Jakobides took on an important role as an educator at the Athens School of Fine Arts. He taught painting for many years, from 1904 until 1925, influencing a significant number of Greek artists who came of age in the early 20th century. His teaching would have emphasized the academic principles he himself had mastered: strong drawing skills, anatomical accuracy, careful composition, and the realistic depiction of light and form.

Among his students were artists who would go on to explore different stylistic paths, but the foundational academic training they received under Jakobides would have provided them with essential technical skills. While the tide of modernism was rising, with artists like Konstantinos Parthenis (1878-1967) and members of the "Techni" group pushing for new forms of expression, Jakobides represented the established academic tradition.

His students would have included figures who continued in a more conservative vein, as well as those who later broke away. For instance, Spyros Papaloukas (1892-1957), though later a key figure in Greek modernism with Impressionist and Fauvist influences, would have passed through the School of Fine Arts during a period when Jakobides' influence was strong. The rigorous training provided a solid base, even for those who eventually diverged from academicism. Jakobides' impact as a teacher, therefore, was in transmitting a high standard of technical proficiency.

Contemporaries and Artistic Milieu

Georgios Jakobides operated within a vibrant and evolving artistic milieu, both in Munich and Athens.

Greek Contemporaries:

He was part of a distinguished generation of Greek artists, many of whom also trained in Munich and are collectively known as the "Munich School" of Greek painting.

Nikolaos Gyzis (1842-1901): One of the most important Greek painters of the 19th century. Gyzis also spent much of his career in Munich and was a professor at the Academy there. His work ranged from genre scenes to allegorical and historical paintings, often with a more idealistic or symbolic dimension than Jakobides'.

Konstantinos Volanakis (1837-1907): The foremost Greek seascape painter, also trained in Munich. While Jakobides focused on figures, Volanakis captured the maritime life and atmosphere of Greece.

Theodoros Rallis (1852-1909): Based primarily in Paris and influenced by French Orientalism, Rallis depicted scenes from the Middle East and Greece, often with a romantic and ethnographic focus.

Polychronis Lembesis (1848-1913): Another Munich School adherent, known for his genre scenes, landscapes, and portraits, often depicting rural Greek life with a gentle realism.

Ioannis Altamouras (1852-1878): A prodigious talent in seascape painting who died young, but whose work showed immense promise, influenced by his studies in Copenhagen.

These artists, along with Jakobides and Lytras, formed the core of 19th-century Greek academic painting, establishing a national school that combined European academic training with Greek themes and sensibilities.

Munich Contemporaries (Non-Greek):

In Munich, Jakobides would have been aware of and interacted with a wide range of German and international artists.

Franz von Lenbach (1836-1904): A highly successful portrait painter in Munich, known for his depictions of prominent figures like Bismarck.

Franz Defregger (1835-1921): As mentioned, his popular genre scenes of Tyrolean life shared some thematic similarities with Jakobides' focus on everyday people, albeit in a different cultural context.

The aforementioned Wilhelm Leibl and his circle represented a more uncompromising form of realism.

The general artistic environment in Munich was rich with academic painters, but also saw the beginnings of the Secession movements towards the end of Jakobides' time there, signaling a shift towards modernism with artists like Franz von Stuck (1863-1928) and later, the early stirrings of Expressionism.

While Jakobides remained committed to academic realism, he was undoubtedly aware of these evolving trends. His interactions with this diverse group of artists would have enriched his understanding of the broader European art scene.

The Munich School and its Greek Adherents

The Munich School was not a monolithic movement but rather a dominant academic approach taught at the Munich Academy of Fine Arts from the mid-19th to the early 20th century. It emphasized:

Technical Proficiency: Mastery of drawing, anatomy, perspective, and the handling of paint.

Realism: A faithful depiction of the visible world, though often idealized or sentimentalized in genre painting.

Chiaroscuro: Dramatic use of light and shadow, often inspired by Dutch Masters like Rembrandt and Frans Hals.

Subject Matter: Genre scenes (everyday life, peasant scenes, domestic interiors), historical paintings, and portraiture.

Narrative Element: Paintings often told a story or depicted a specific moment with emotional content.

Greek artists flocked to Munich because it offered high-quality academic training and was perceived as a more conservative and disciplined environment than Paris, which was increasingly becoming the center of avant-garde movements. For a nation like Greece, still forging its modern identity, the established traditions of the Munich School provided a solid foundation for developing a national artistic voice.

Jakobides, along with Lytras and Gyzis, became leading exponents of this style in Greece. They adapted its principles to depict Greek subjects, characters, and customs, contributing to a sense of cultural self-representation. Jakobides, in particular, excelled in the genre aspect, creating images of Greek family life that were both technically accomplished and emotionally resonant. His work helped to popularize this style among the Greek bourgeoisie, who appreciated its craftsmanship and sentimental appeal.

Lasting Influence and Critical Reception

Georgios Jakobides enjoyed immense popularity during his lifetime. His paintings were widely reproduced and admired for their technical skill, charm, and relatable subject matter. He received numerous awards and honors, both in Greece and internationally. His role as the first director of the National Gallery further solidified his esteemed position in the Greek art world.

However, as artistic tastes began to shift in the early 20th century with the rise of modernism, Jakobides' unwavering adherence to academic realism came to be seen by some as conservative or old-fashioned. The new generation of artists, influenced by Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, Fauvism, and Cubism, sought to break away from academic constraints and explore new forms of expression. Figures like Konstantinos Maleas (1879-1928) and Parthenis championed these new approaches.

Despite these shifts, Jakobides' work has retained a special place in the hearts of the Greek public. His paintings continue to be celebrated for their warmth, humanity, and masterful execution. Art historians recognize him as a key figure in 19th-century Greek art, a master of the Munich School style, and an artist who perfectly captured the ethos of his time. While his direct stylistic influence waned with the advent of modernism, his contribution to establishing a high standard of technical excellence and his role in shaping national cultural institutions remain undeniable.

His paintings are considered national treasures, and their enduring appeal testifies to his skill in connecting with fundamental human emotions. The tenderness with which he depicted children and family life transcends stylistic changes, ensuring his continued relevance and appreciation.

Exhibitions and Institutional Recognition

Throughout his career, Georgios Jakobides participated in numerous important exhibitions, both in Greece and abroad, which contributed to his international reputation.

International Exhibitions:

He exhibited regularly in Munich while living there, and his works were also shown in other major European art centers, including Paris (notably the Exposition Universelle), Berlin, and Vienna.

He received several medals and distinctions at these international showcases, such as a gold medal in Athens (1875), an award at the Paris International Exposition of 1878, a gold medal in Berlin (1891), and the "Ritterkreuz" (Knight's Cross) in Munich. He also won a gold medal at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1900 for "Children's Concert."

Greek Exhibitions:

In Greece, he was a regular participant in the Panhellenic Exhibitions held at the Zappeion Megaron in Athens. These exhibitions were crucial events in the Greek art calendar.

His works were, and continue to be, prominently featured in retrospectives and group shows dedicated to 19th-century Greek art.

Major Collecting Institutions:

Today, Georgios Jakobides' paintings are held in high esteem and are found in major public and private collections.

National Gallery of Greece, Athens: This institution holds the most significant collection of his works, including many of his masterpieces like "Children's Concert" and "Grandfather's New Pipe." His role as its first director makes his presence there particularly poignant.

Averoff Gallery, Metsovo: Another important museum in Greece that houses a fine collection of 19th and 20th-century Greek art, including works by Jakobides.

Koutlidis Collection, Athens: This significant private collection, now part of the National Gallery, also features works by Jakobides.

Municipal Galleries: Various municipal galleries throughout Greece also own and display his paintings.

Private Collections: Many of his works remain in private hands, both in Greece and internationally, a testament to his enduring popularity among collectors.

His institutional recognition is further cemented by his long service as a professor at the Athens School of Fine Arts and his directorship of the National Gallery. These roles underscore his importance not just as a painter but as a shaper of Greece's artistic infrastructure. His legacy is preserved not only through his canvases but also through the institutions he helped build and the students he inspired. His art continues to be a touchstone for understanding the cultural and social values of late 19th and early 20th-century Greece.