Introduction: Navigating the Historical Record

The study of art history often involves piecing together fragmented information, and the case of Albert Clark (1821-1909) presents a fascinating, if somewhat intricate, puzzle. While a distinct artistic figure emerges from this period, primarily known for his skill in animal portraiture, the name "Albert Clark" also appears in connection with other fields and later artistic movements, leading to potential confusion. This exploration aims to shed light on the life and work of Albert Clark, the Victorian animal painter, situating him within his artistic milieu, while also carefully addressing other attributions associated with the name to provide a clearer, more nuanced understanding.

The primary Albert Clark under discussion here was a British artist who flourished during the Victorian era, a period marked by a burgeoning middle class with a keen interest in art that reflected their lives, values, and pastimes, including a deep affection for animals. This Albert Clark specialized in capturing the likenesses of horses, dogs, and other creatures, contributing to a popular and enduring genre. However, it is crucial at the outset to acknowledge that information provided in initial queries can sometimes merge details from disparate individuals. For instance, references to studies on ancient prose rhythm or avant-garde compositions from the mid-20th century point to different individuals entirely, and these will be contextualized separately to avoid misattribution.

The Life of Albert Clark, Animal Painter

Albert Clark was born in England in 1821 and died in 1909. Specific details about his early life, formal artistic training, and precise nationality (beyond being British) are not always extensively documented in easily accessible public records, which is not uncommon for artists who, while successful, may not have achieved the towering fame of some of their contemporaries. He was, however, part of a family of artists, a common phenomenon in the 19th century where skills and studio practices were often passed down through generations. His sons, Albert Clark Jr. and William Albert Clark, also became painters, continuing the tradition of animal artistry.

Clark primarily worked in London, the vibrant heart of the British art world. During his lifetime, the Royal Academy of Arts was the preeminent institution, and artists often sought to exhibit there to gain recognition and patronage. While comprehensive exhibition records for Clark at major institutions like the Royal Academy require detailed archival research, his body of work suggests a consistent demand for his specialized skills. He catered to a clientele that cherished their animals, from prized racehorses and loyal hunting dogs to beloved domestic pets. His career spanned a significant portion of the Victorian era and extended into the Edwardian period, witnessing considerable shifts in artistic tastes and styles.

Artistic Specialization: The World of Animals

Albert Clark carved a niche for himself as an animal painter, or "animalier," a genre that enjoyed immense popularity in 19th-century Britain. This was an era of great sentimentality towards animals, coupled with a practical reliance on them for sport, agriculture, and companionship. The English countryside, with its hunts, farms, and estates, provided ample subject matter. Clark's paintings typically feature horses and dogs, rendered with anatomical accuracy and an evident appreciation for their individual character.

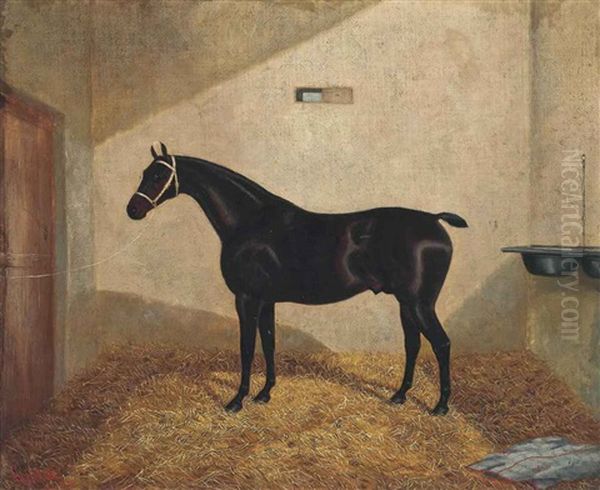

His style can be characterized as Victorian realism. He paid close attention to the texture of fur and hide, the musculature of the animals, and the details of their tack or surroundings. Unlike some animal painters who leaned towards highly romanticized or anthropomorphized depictions, Clark's work often maintained a more straightforward, portrait-like quality. His compositions are generally well-balanced, focusing on the animal as the central subject, often depicted in stable interiors, kennels, or pastoral landscapes. The lighting is usually naturalistic, highlighting the form and coat of the animal.

This dedication to animal subjects places him in a lineage that includes earlier masters like George Stubbs (1724-1806), whose scientific approach to equine anatomy revolutionized animal painting, and Sawrey Gilpin (1733-1807). Clark's contemporaries in this field were numerous, reflecting the genre's appeal.

Signature Works and Themes

While a comprehensive catalogue raisonné of Albert Clark's work is a scholarly undertaking, several paintings consistently appear in auction records and collections, giving us insight into his typical output. Titles often reflect the subject matter directly, such as "A Prize Pair," "Chestnut Hunter in a Stable," "Terriers Ratting," or portraits of specific, named animals commissioned by their owners.

"Chestnut Hunter in a Stable," for example, would likely showcase a prized horse, meticulously rendered, perhaps with a gleaming coat, standing patiently in a detailed stable setting. Such paintings were not just depictions of animals but also symbols of status and a particular way of life. The inclusion of details like polished tack, clean straw, and well-maintained surroundings would speak to the owner's pride and care.

Paintings of terriers, such as "Terriers Ratting," tap into another aspect of Victorian interest in animals – their working roles and perceived characteristics. Terriers were valued for their tenacity and vermin-control abilities. Clark would capture their alert expressions and energetic postures, appealing to an audience that admired these traits. His ability to convey the individual personality of each animal, whether a noble steed or a feisty terrier, was a key element of his appeal.

Other common themes would include portraits of gundogs with game, hounds, and family pets. These works often possess a quiet dignity, focusing on the bond between humans and animals, even if the human owner is not always depicted. The settings, whether a comfortable domestic interior or a more rugged outdoor scene, are usually rendered with care, providing context and enhancing the overall realism of the portrayal.

A Family Legacy in Art

The artistic tradition in the Clark family did not end with Albert Clark Sr. His sons, Albert Clark Jr. (sometimes recorded as Albert Clark II, active c. 1870-1910 or with slightly varying dates) and William Albert Clark (active late 19th to early 20th century), followed in his footsteps, also specializing in animal painting. This familial connection is significant, as it suggests a shared studio environment, mutual learning, and a continuation of a particular artistic focus.

It can sometimes be challenging for art historians to definitively distinguish between the works of family members who paint in similar styles and tackle similar subjects, especially if signatures are similar or works are unsigned. However, the presence of multiple Clark animal painters underscores the sustained market for such art. Albert Clark Jr.'s work often mirrors his father's in subject and style, focusing on horses and dogs with a similar realistic approach. William Albert Clark also contributed to this genre. Their collective output represents a significant contribution to Victorian and Edwardian animal painting.

The continuation of this specialty within the family highlights the professional networks and training methods of the time. Apprenticeship, often within the family, was a common route to becoming an artist, ensuring the transmission of specific techniques and knowledge related to popular genres.

Victorian England: The Artistic Milieu

To fully appreciate Albert Clark's work, it's essential to understand the artistic climate of Victorian England (1837-1901). This era was characterized by industrial progress, colonial expansion, and a growing, affluent middle class. Art became more accessible and sought after by a wider range of people beyond the traditional aristocracy. The Royal Academy's annual exhibitions were major social events, and popular paintings were often reproduced as prints, reaching an even broader audience.

Animal painting, in particular, resonated deeply. Queen Victoria herself was a great animal lover, and her patronage influenced tastes. Artists like Sir Edwin Landseer (1802-1873) achieved immense fame with his dramatic and often sentimental depictions of animals, such as "The Monarch of the Glen." Landseer's ability to imbue animals with human-like emotions and narratives captivated the public. While Clark's style was generally more restrained than Landseer's, he operated within the same cultural appreciation for animal subjects.

Other prominent animal painters of the era included John Frederick Herring Sr. (1795-1865) and his sons, who were renowned for their coaching scenes and racehorse portraits. Briton Rivière (1840-1920) was another popular artist known for his animal subjects, often with narrative or historical themes. The French artist Rosa Bonheur (1822-1899) also gained international acclaim, including in Britain, for her powerful animal paintings, particularly "The Horse Fair." These artists, along with many others, created a rich tapestry of animal art that catered to diverse tastes, from the sporting enthusiast to the pet owner.

Beyond animal painting, the Victorian art world was diverse. The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, with figures like Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882), John Everett Millais (1829-1896), and William Holman Hunt (1827-1910), challenged academic conventions with their detailed realism and literary themes. Narrative painting, depicting scenes from history, literature, or contemporary life, was also highly popular, exemplified by artists like William Powell Frith (1819-1909). Albert Clark's work, while specialized, existed within this broader, dynamic artistic landscape.

Contemporaries and Influences in Animal Painting

The field of animal painting in the 19th century was competitive and vibrant. Albert Clark would have been aware of, and likely influenced by, the leading animaliers of his time. As mentioned, Sir Edwin Landseer was a dominant figure whose technical skill and ability to connect with public sentiment set a high standard. His influence was pervasive, encouraging a focus on anatomical accuracy combined with expressive portrayal.

John Frederick Herring Sr. was particularly famous for his depictions of racehorses and farm scenes. His detailed and lively compositions were highly sought after. The tradition of sporting art, which included hunting scenes, racing, and depictions of prized livestock, had a long history in Britain, with earlier artists like George Morland (1763-1804) and James Ward (1769-1859) also making significant contributions that shaped the genre.

Later in the century, artists like John Emms (1843-1912) became well-known for their spirited paintings of hounds and terriers, often characterized by a looser, more painterly style than Clark's typically tighter rendering. Maud Earl (1864-1943) was another notable female artist who gained recognition for her sensitive dog portraits towards the end of Clark's career and into the 20th century.

The demand for animal portraits meant that artists like Clark could sustain a career by focusing on this niche. Patrons often commissioned portraits of their specific animals, requiring the artist to capture not just a generic representation of the breed, but the individual characteristics of their cherished companion or valuable working animal. This required keen observation and the ability to work from life, or at least from detailed sketches made from life.

Addressing Other Attributed Information: Clarifying the Record

It is important to address the other pieces of information that were initially associated with an "Albert Clark" in the query, as these point to different individuals and fields, and their inclusion without clarification would misrepresent the Victorian animal painter.

One piece of information mentioned "Albert Clark's main contribution... study on ancient prose rhythm... Antique Prose-Rhythm Handbook." This refers to Albert Curtis Clark (1859–1937), a distinguished British classical scholar and Professor of Latin at the University of Oxford. His work on Latin palaeography, textual criticism (especially of Cicero), and prose rhythm is highly regarded in classical studies but is entirely unrelated to the visual arts or the painter Albert Clark (1821-1909). The methods described, such as statistical analysis of syllable combinations, are characteristic of philological research.

Another statement referred to "Albert Clark's 1954 work Compositions... blurred boundaries... led to the demise of painting as an independent medium." This description, particularly the date 1954 and the conceptual nature of the work, strongly suggests a mid-20th-century avant-garde artist. This does not align with Albert Clark (1821-1909), who died long before 1954. This might be a confusion with an artist from a later period, perhaps even a misremembered reference to someone like the Brazilian artist Lygia Clark (1920-1988), who was a prominent figure in the Neo-Concrete movement and whose work indeed explored the boundaries of the art object and viewer participation, often challenging traditional notions of painting. The idea of the "demise of painting as an independent medium" is a concept debated within post-war art theory, associated with movements like Conceptual Art and Minimalism, far removed from Victorian animal painting.

The mention of the "Clark Prize" is also broad. There are several prestigious "Clark" prizes. The John Bates Clark Medal is a significant award in economics. The Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute (often referred to as "The Clark") in Williamstown, Massachusetts, is a major art museum and research institution founded by Sterling Clark (1877-1956) and his wife Francine. While it is a key institution in art history, it is not directly tied to the artistic output of Albert Clark the painter. Similarly, references to T.J. Clark (Timothy James Clark, born 1943), a highly influential British Marxist art historian known for his social history of art approach, or Kenneth Clark (Kenneth McKenzie Clark, Baron Clark, 1903–1983), another eminent British art historian, author, and broadcaster (famous for the "Civilisation" television series), pertain to art historical scholarship, not the practice of painting by Albert Clark (1821-1909).

It is common for names to recur across different fields and generations, and careful research is needed to distinguish between individuals. The Albert Clark who painted animals in the Victorian era operated in a distinct historical and artistic context from these other figures.

The Enduring Appeal of Animal Art

The genre of animal painting, to which Albert Clark dedicated his career, has an enduring appeal. It speaks to the deep connection between humans and the animal kingdom, a bond that transcends time and cultural shifts. In the Victorian era, this connection was multifaceted: animals were companions, status symbols, essential components of sport and agriculture, and subjects of scientific curiosity. Clark's work tapped into all these aspects.

His paintings, and those of his contemporaries, offer a window into the values and aesthetics of the Victorian period. The meticulous realism, the focus on individual animal character, and the often sentimental or appreciative portrayal reflect the tastes of his patrons. While art history has often prioritized avant-garde movements and grand historical narratives, the study of genre painting, including animal art, provides valuable insights into the broader cultural landscape.

Artists like Clark provided a service that was highly valued: immortalizing beloved animals and celebrating a way of life closely intertwined with the natural world and animal husbandry. The continued presence of his works in art markets and collections today attests to their lasting charm and historical interest.

Conclusion: Albert Clark's Place in Art History

Albert Clark (1821-1909) was a skilled and dedicated British animal painter who contributed to a popular and significant genre within Victorian art. His work is characterized by its realistic depiction of horses, dogs, and other animals, capturing their individual likenesses and reflecting the deep affection and importance placed on animals during that era. As part of a family of artists specializing in this field, he represents a tradition of craftsmanship and specialized artistic production.

While perhaps not an innovator on the scale of some of his more famous contemporaries like Landseer, Clark's paintings possess a quiet integrity and technical competence that found a ready market. His contributions are best understood within the context of Victorian realism and the specific demands of animal portraiture.

It is also vital to distinguish him from other notable individuals named Clark in different fields, such as Albert Curtis Clark the classical scholar, or from broader references to figures like T.J. Clark or Kenneth Clark in art history, or even from avant-garde artists of the 20th century. By focusing on the specific historical and artistic context of Albert Clark the animal painter, we can appreciate his role in the rich tapestry of 19th-century British art. His legacy, and that of his sons, lies in the charming and faithful depictions of animals that continue to be appreciated by collectors and enthusiasts of Victorian art and animal painting.