Basil Nightingale (1864-1940) stands as a distinguished figure in the annals of British art, particularly celebrated for his evocative and skilfully rendered depictions of animals and the vibrant world of country sports. Working primarily during the late Victorian and Edwardian eras, and into the interwar period, Nightingale captured the essence of British rural life, with a special focus on equestrian subjects and hunting scenes. His oeuvre, encompassing watercolors, charcoals, and oils, is characterized by a keen observational eye, a dynamic sense of movement, and a profound understanding of animal anatomy.

The Artistic Landscape of Nightingale's Era

To appreciate Basil Nightingale's contribution, it's essential to understand the artistic milieu in which he worked. The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw a continued, robust tradition of sporting art in Britain, a genre that had gained immense popularity with artists like George Stubbs in the 18th century, whose anatomical precision set a high benchmark. By Nightingale's time, this tradition was well-established, with patrons among the landed gentry and a wider public appreciative of scenes depicting hunting, racing, and pastoral life.

Artists such as John Frederick Herring Sr. and his sons had already cemented the popularity of equestrian portraiture and racing scenes. Nightingale's direct contemporaries included luminaries like Sir Alfred Munnings, who would become one of the most famous British equestrian artists, known for his vigorous and impressionistic style. Others, like Lionel Edwards, Cecil Aldin, and "Snaffles" (Charles Johnson Payne), also specialized in hunting, coaching, and military equestrian subjects, each bringing their unique flair to the genre. Nightingale's work, therefore, emerged within a competitive and highly skilled field, yet he carved out his own distinct niche.

Early Life and Artistic Development

Specific details regarding Basil Nightingale's early life, formal artistic training, and formative influences are not extensively documented in readily available public records. This is not uncommon for artists of his period who may not have achieved the same level of widespread fame as some of their peers during their lifetime, or whose personal papers have not been preserved or made accessible. However, one can infer certain aspects from the nature and quality of his work.

His profound understanding of animal anatomy, particularly that of horses and hounds, suggests dedicated study, either through formal art schooling that included anatomical drawing, or through direct and prolonged observation in the field – a common practice for sporting artists. The confidence in his brushwork and the sophisticated compositions evident in his paintings point to a well-honed skill set, developed over years of practice. It is plausible that he received tuition from established artists or attended one of the many art academies flourishing in Britain at the time. The prevailing artistic climate would have exposed him to various styles, from the detailed realism of the Pre-Raphaelites to the burgeoning influence of Impressionism, though his own work largely adheres to a more traditional, representational approach well-suited to sporting art.

Artistic Style and Techniques

Basil Nightingale's artistic style is marked by its meticulous attention to detail, combined with a remarkable ability to convey the energy and spirit of his subjects. He was adept in several media, demonstrating versatility and a mastery of different techniques.

In his watercolors, often his preferred medium for hunting scenes and animal studies, Nightingale displayed a fluid yet controlled application. He frequently utilized bodycolour, or gouache, particularly white heightening, to add highlights, create contrast, and define form, giving his watercolors a notable vibrancy and depth. This technique allowed him to capture the sheen of a horse's coat, the glint of light on a bridle, or the crispness of a winter landscape. His compositions are typically well-balanced, drawing the viewer's eye effectively through the scene.

His oil paintings, while perhaps less numerous in his publicly known oeuvre, demonstrate a similar commitment to realism and anatomical accuracy. Works like Charles Tuller Garland, Esq. on Thermos showcase his ability to handle the richer textures and deeper tones afforded by oils, creating substantial and commanding portraits of both rider and mount.

Across his work, Nightingale showed a particular talent for depicting animals in motion. Whether it was the full-stretch gallop of a racehorse, the determined pursuit of hounds, or the subtle tension of an animal in a "critical moment," he managed to freeze action without sacrificing its inherent dynamism. His palette was generally naturalistic, reflecting the true colours of the British countryside and the animals within it, though he was not afraid to use stronger colours to enhance the dramatic impact of a scene.

Key Themes in Nightingale's Work

Nightingale's thematic concerns revolved primarily around the traditional pursuits of the British countryside, with a strong emphasis on animals, particularly horses and dogs.

Equestrian Portraits and Horse Studies

A significant portion of Nightingale's work involved the portrayal of horses. These were not just generic representations but often specific, commissioned portraits of prized hunters, racehorses, or carriage horses. Works such as The racehorse Abbeywood in a stable exemplify his skill in capturing the individual character and conformation of the animal. He paid close attention to the musculature, the set of the head and neck, and the overall bearing of the horse, satisfying the discerning eyes of his patrons who were often knowledgeable equestrians themselves.

The Thrill of the Hunt

Hunting scenes were a cornerstone of Nightingale's output. He excelled at depicting the various stages of the foxhunt – the meet, the chase, and sometimes the more challenging aspects of pursuit and capture. These paintings are often complex, multi-figure compositions, featuring riders in their distinctive hunt liveries, a pack of hounds in full cry, and the dynamic landscape of the British shires. He captured the excitement, the speed, and the collaborative effort of the hunt with great verve. His understanding of hound behaviour and the interaction between hounds, horses, and riders lent an authenticity to these scenes that resonated with those familiar with the sport. Artists like Heywood Hardy and John Emms (known especially for his depictions of hounds) also worked extensively in this area, and Nightingale's contributions stand proudly alongside theirs.

Animal Studies and Rural Life

Beyond the hunt and formal equestrian portraits, Nightingale also produced studies of other animals and scenes of rural life. His depictions of dogs, whether working hounds or companion animals, were rendered with sensitivity and an appreciation for their individual characteristics. The broader context of the countryside, with its changing seasons and varied landscapes, often formed an integral backdrop to his primary subjects, painted with an eye for atmospheric detail. This places him in a lineage that includes artists like Richard Ansdell, known for his animal and sporting scenes, often with a Scottish flavour, and Archibald Thorburn, a master of wildlife, particularly bird, illustration.

Notable Works

Several of Basil Nightingale's works have gained recognition and are frequently cited when discussing his career.

Well Known With the Quorn (1930): This watercolor, completed a decade before his death, is a quintessential example of his hunting scenes. The Quorn Hunt is one of the oldest and most famous fox hunts in England, and Nightingale's depiction would have resonated strongly with the sporting community. The work likely captures the energy and pageantry of a Quorn meet or chase, showcasing his mature style and confident handling of complex group compositions. The date indicates his continued activity and relevance in the art world well into the 20th century.

Charles Tuller Garland, Esq. on Thermos (1913): An oil painting, this work is a fine example of a commissioned equestrian portrait. It depicts a specific individual, Charles Tuller Garland, mounted on his horse, Thermos. Such portraits were popular among the affluent, serving as records of prized animals and affirmations of social standing. The medium of oil allows for a richness and formality suited to such a commission. The painting's recorded sale price at auction in more recent times (£1,500-£2,500) indicates a continued appreciation for his work in this genre.

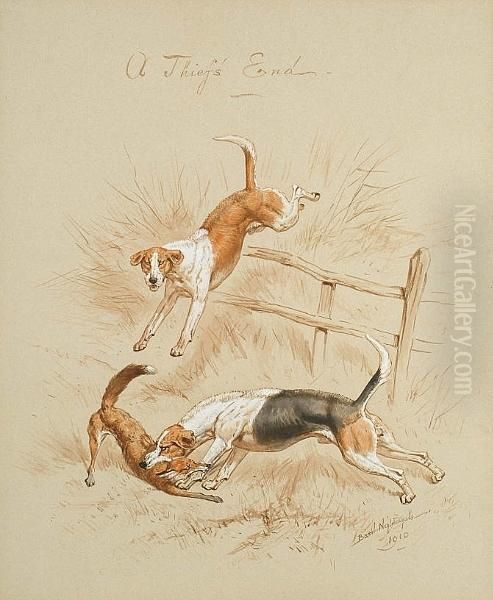

Crime & Retribution (1913): This is described as a pair of watercolors, a diptych format that allows for a narrative or contrasting theme. One part reportedly shows a fox with a dead chicken, representing the "crime" from a farmer's perspective, while the other depicts hounds with the head of a dead fox, the "retribution" from the hunt's viewpoint. This thematic pairing showcases Nightingale's ability to engage with the more dramatic and sometimes controversial aspects of rural life and the natural world. The estimated auction value of £200-£300 for the pair reflects the market for his smaller watercolor works. The use of black lead pencil and coloured washes, heightened with white, is typical of his watercolor technique.

A Critical Moment (1919): The title itself suggests a scene of tension or pivotal action, a common motif in sporting art. While specific details of this work's composition are not provided in the initial summary, it likely captures a dramatic instant in a hunt or a race, showcasing Nightingale's skill in conveying suspense and animal instinct.

Tally-Ho and Crime (1924): Similar to Crime & Retribution, this title suggests a narrative related to hunting and perhaps the perceived "crimes" of the fox. "Tally-Ho" is the traditional cry of a huntsman on sighting the fox, indicating a work that likely captures the commencement or height of a chase.

The racehorse Abbeywood in a stable: This title points to a more serene, portrait-style depiction of a racehorse, likely commissioned by its owner. Stable portraits were a popular sub-genre, allowing for a detailed study of the horse's physique and temperament in a controlled setting. Artists like Maud Earl, though more famous for her dog portraits, and Lucy Kemp-Welch, renowned for her powerful depictions of horses in various settings including working horses and military scenes, also contributed to the rich tapestry of animal portraiture in Britain.

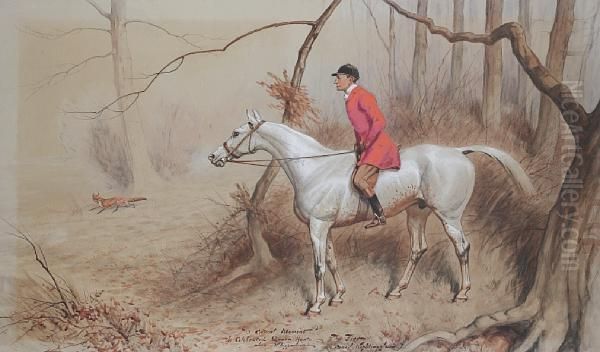

Tom Firr on Whitelegs: This is noted as a series of prints, possibly posthumous, based on an original painting by Nightingale. Tom Firr was a celebrated huntsman for the Quorn Hunt for 27 seasons (1872-1899). If Nightingale painted him, it would have been a significant subject. A print series based on such a painting, even if produced later (the source mentions a 1998 painting, which is anachronistic for Nightingale's life but could refer to the print's production or a copy), would aim to make a popular image more widely accessible. The dimensions provided (45 x 30 cm image, 50 x 36 cm sheet) are typical for such prints.

Nightingale's Place in the Sporting Art Tradition

Basil Nightingale operated within a strong and continuing tradition of British sporting art. His work upheld the values of anatomical accuracy, skilled draughtsmanship, and an intimate knowledge of his subjects that were hallmarks of the genre's best practitioners. While he may not have sought the radical innovations of some modernist painters of his era, his dedication to his chosen field contributed to its enduring appeal.

His contemporaries, such as the aforementioned Sir Alfred Munnings, Lionel Edwards, and Cecil Aldin, each brought their individual styles to sporting art. Munnings was known for his bolder, more impressionistic handling of paint and light; Edwards for his atmospheric hunting scenes, often in watercolor; and Aldin for his charming, somewhat stylized depictions of dogs and country life. Nightingale's style, while perhaps more traditional and meticulously detailed than Munnings, shared with these artists a deep affection for and understanding of the British countryside and its pursuits. Other artists like George Denholm Armour also contributed significantly to the visual record of equestrian sports during this period.

The market for Nightingale's work, as evidenced by auction records, shows a consistent, if not always spectacular, level of interest. This indicates a steady appreciation among collectors of sporting art and those who value well-executed, traditional representations of British heritage subjects. His paintings serve not only as aesthetic objects but also as historical documents, capturing a way of life and a set of traditions that were central to a particular segment of British society.

Personal Life and Legacy

As is common with many artists who were not figures of major public celebrity, detailed information about Basil Nightingale's personal life, beyond his birth and death dates (1864-1940), is not widely publicized. The provided information contains some potential confusion with other individuals named Nightingale, particularly the renowned Florence Nightingale and her family, or possibly other Basil Nightingales. For instance, details about a marriage to a "Jean" in 1935 (when Basil the painter would have been 71), children named Tom, Philip, and Peta, retirement to Broadstairs, and involvement with a "Florence Nightingale Lodge" seem to refer to a different individual or are misattributed. Similarly, anecdotes about refusing marriage to pursue a career, a wealthy upper-class upbringing with a father supporting education, specific religious beliefs, and a political career as a secretary to the Archbishop of York or in Ceylon, are characteristic of Florence Nightingale or her father, William Edward Nightingale, not the painter Basil Nightingale, based on current art historical records.

The primary legacy of Basil Nightingale the painter lies firmly in his artistic output. He was a dedicated and skilled chronicler of equestrian and sporting life in Britain. His works are valued for their accuracy, their aesthetic appeal, and their evocation of a specific era and culture. He contributed to a genre that, while sometimes overlooked by mainstream art history focused on avant-garde movements, holds a significant place in Britain's cultural heritage. His paintings continue to be appreciated by enthusiasts of sporting art, collectors, and those with an interest in rural history.

His ability to capture the unique conformation of a horse, the focused intensity of hounds, and the dynamic interplay of figures in a landscape ensures his work remains engaging. While he may not have been an innovator in the modernist sense, his mastery within his chosen field was considerable. He provided his patrons and subsequent audiences with vivid, enduring images of the animals and activities they cherished.

Conclusion

Basil Nightingale (1864-1940) was a talented British artist who specialized in animal and sporting subjects, creating a body of work that is both historically significant and artistically accomplished. Working in watercolor, charcoal, and oil, he produced detailed and spirited depictions of horses, hounds, and the hunting field, capturing the essence of British rural traditions. His paintings, such as Well Known With the Quorn, Charles Tuller Garland, Esq. on Thermos, and the Crime & Retribution pair, showcase his keen eye for anatomical detail, his ability to convey movement and character, and his mastery of traditional painting techniques.

He worked during a period rich in sporting artists, alongside figures like Sir Alfred Munnings, Lionel Edwards, and Cecil Aldin, and his contributions hold their own within this distinguished company. While specific details of his personal life are not as well-documented as his artistic endeavors, his legacy endures through his paintings, which continue to be appreciated for their skill, authenticity, and their evocative portrayal of a cherished aspect of British heritage. Basil Nightingale remains a noteworthy figure for anyone interested in the history of British sporting art and animal portraiture.