The surname Van Dyck resonates powerfully within the annals of art history, primarily evoking the image of a seventeenth-century Flemish Baroque master. However, the passage of time has seen other artists bear this name, leading to occasional points of clarification. This exploration delves into the lives and works associated with the Van Dyck name, focusing on the celebrated Anthony van Dyck, while also acknowledging the twentieth-century artist Albert Van Dyck, ensuring that the distinct contributions and historical contexts of each are respectfully presented. The art world is a tapestry woven with threads of influence, collaboration, and innovation, and the story of "Van Dyck" touches upon many of these facets.

Albert Van Dyck: A Twentieth-Century Perspective

Information regarding Albert Van Dyck (1902-1951) is comparatively scarce in widely accessible art historical records, especially when contrasted with his famous namesake. According to the available data, Albert Van Dyck was an artist whose life spanned the first half of the twentieth century. He was born in 1902 and passed away in 1951. His identity as an artist is confirmed, and at least one of his works is noted: a painting depicting peasants engaged in labor near a village. This subject matter suggests an interest in genre scenes or social realism, themes that were indeed explored by various artists during his lifetime, reflecting a departure from purely academic or avant-garde concerns towards the depiction of everyday life.

The specific birthplace of Albert Van Dyck is not clearly mentioned in the provided preliminary information. While the name Van Dyck has strong associations with Antwerp, Belgium, due to Anthony van Dyck, it's crucial not to conflate the biographical details of these two distinct individuals. The early to mid-twentieth century was a period of immense artistic diversity, with movements ranging from Surrealism and Art Deco to various forms of Realism and Abstraction. Without further specific details on Albert Van Dyck's training, artistic circle, or a broader catalogue of his works, it is challenging to place him definitively within these currents. His focus on peasant life, however, could align him with artists who found dignity and narrative power in the lives of ordinary working people, a tradition with roots stretching back through artists like Jean-François Millet in the 19th century.

The limited information available prevents a detailed discussion of Albert Van Dyck's specific artistic style, his influences, or his impact on contemporaries. His lifespan places him amidst a turbulent period in European history, encompassing two World Wars and significant societal shifts, which often found reflection in the arts. Artists of this era, such as Käthe Kollwitz in Germany or Grant Wood in America, also depicted common people and rural life, albeit with their own distinct styles and motivations. Further research into regional archives or specialized catalogues of Belgian art from that period might yield more comprehensive insights into Albert Van Dyck's career, his artistic contributions, and his place within the broader narrative of twentieth-century European art. For now, he remains a figure noted for his existence and a glimpse into his thematic concerns.

Anthony van Dyck: The Quintessential Baroque Portraitist

When art historians speak of Van Dyck, they are almost invariably referring to Sir Anthony van Dyck (1599-1641), a Flemish Baroque artist who became the leading court painter in England after achieving significant success in Italy and Flanders. His influence on European portraiture, particularly in Britain, was profound and lasted for generations. His ability to imbue his sitters with an effortless elegance and refined authority set a new standard for aristocratic representation.

Early Life and Prodigious Talent in Antwerp

Born in Antwerp on March 22, 1599, Anthony van Dyck was the seventh of twelve children born to Frans van Dyck, a prosperous silk and cloth merchant, and Maria Cupers. His artistic talent was evident from a young age. By 1609, at the tender age of ten, he was already studying painting with Hendrick van Balen the Elder, a respected Antwerp painter of mythological and religious scenes and a dean of the Antwerp Guild of Saint Luke. Van Balen's studio would have provided a solid foundation in the technical aspects of painting, composition, and the prevailing artistic tastes of the time.

Van Dyck was an independent painter by 1615 or 1616, establishing his own studio even before he officially became a master in the Antwerp Guild of Saint Luke in February 1618. His precocity was remarkable. During this early period, from roughly 1617 to 1620, he worked as a chief assistant to Peter Paul Rubens, who was then the undisputed giant of Northern European Baroque art. Rubens, a master of dynamic compositions, vibrant color, and dramatic intensity, referred to the young Van Dyck as "the best of my pupils." Working in Rubens's highly organized and prolific workshop was an invaluable experience, exposing Van Dyck to large-scale commissions, sophisticated workshop practices, and the height of Baroque artistic expression. Artists like Jacob Jordaens were also prominent in Antwerp at this time, contributing to the city's vibrant artistic milieu, though Jordaens's style often leaned towards a more robust, earthy realism compared to the increasing refinement Van Dyck would later cultivate.

The Italian Sojourn: Refining a Vision

In October 1620, at Rubens's encouragement and possibly with his assistance, Van Dyck made his first brief trip to England, where he worked for King James I. However, Italy, the cradle of the Renaissance and a vital center for Baroque art, beckoned. He traveled to Italy in late 1621, remaining there for six years, a period crucial for his artistic development. He based himself primarily in Genoa, a wealthy port city whose patrician families were eager for his sophisticated portraiture. He also spent time in Rome, Venice, Florence, Mantua, and Palermo.

During his Italian years, Van Dyck assiduously studied the great Italian masters. He was particularly captivated by the Venetian School, especially the works of Titian, whose use of color, composition, and dignified portrayal of sitters profoundly influenced him. He also absorbed lessons from Paolo Veronese and Tintoretto. His Italian sketchbooks, filled with drawings after these masters, attest to his diligent study. It was in Italy that Van Dyck began to develop his signature style of portraiture: elongated figures, refined poses, rich textures, and an air of aristocratic nonchalance. His portraits of Genoese nobility, such as Marchesa Elena Grimaldi Cattaneo or Agostino Pallavicini, showcase this evolving elegance and psychological insight. He also continued to paint religious and mythological subjects, though portraiture was increasingly becoming his forte.

Return to Antwerp and International Acclaim

Van Dyck returned to Antwerp in 1627, his reputation significantly enhanced by his Italian experiences. For the next five years, he was highly successful in his native city, receiving numerous commissions for portraits from the Flemish aristocracy and wealthy bourgeoisie, as well as altarpieces for churches. His style during this period, while retaining Italianate elegance, also re-engaged with the Flemish tradition's attention to detail and texture. He painted portraits of fellow artists, scholars, and patrons, contributing to his "Iconography," a series of etchings and engravings of famous contemporaries, which further spread his fame. Artists like Frans Hals in the nearby Dutch Republic were also revolutionizing portraiture with a more spontaneous, characterful approach, offering a contrast to Van Dyck's courtly grace.

His international renown continued to grow. He received commissions from Archduchess Isabella Clara Eugenia, the Habsburg regent of the Southern Netherlands, and from various European courts. His ability to capture not just a likeness but also the status and personality of his sitters made him highly sought after. He was a contemporary of other great European Baroque masters like Diego Velázquez in Spain, who similarly excelled in court portraiture, and Nicolas Poussin in France, who focused more on classical and historical subjects.

Principal Painter in Ordinary to Charles I of England

The most defining phase of Van Dyck's career began in April 1632 when he moved to England at the invitation of King Charles I. Charles I was a passionate art collector and patron, and he saw in Van Dyck an artist who could project the desired image of majesty, culture, and divine authority for the Stuart monarchy. Van Dyck was an immediate success. He was knighted in July 1632 and appointed "Principal Painter in Ordinary to their Majesties." He was provided with a house on the River Thames at Blackfriars, outside the jurisdiction of the London painters' guild, and a summer residence in Eltham Palace. A generous pension of £200 a year was granted, though its payment was often irregular.

In England, Van Dyck revolutionized portrait painting. He created numerous iconic portraits of Charles I, Queen Henrietta Maria, their children, and members of the English aristocracy. His portraits conveyed an unprecedented air of relaxed authority and sophisticated grace. Works like "Charles I at the Hunt" (c. 1635), "Charles I in Three Positions" (c. 1635-36, sent to the sculptor Gian Lorenzo Bernini in Rome as a model for a bust), and the "Great Peece" (Charles I and Henrietta Maria with their two eldest children, 1632) defined the image of the Caroline court. His influence was so pervasive that English portraiture for the next century and a half was largely indebted to his style. Artists like William Dobson and Robert Walker were among the first to follow in his footsteps, and later painters such as Sir Peter Lely and Sir Godfrey Kneller, who dominated English portraiture in the later 17th century, built upon the foundations he laid. Even later, masters like Thomas Gainsborough and Sir Joshua Reynolds in the 18th century looked back to Van Dyck as a primary source of inspiration for aristocratic portraiture.

Van Dyck's English studio was highly productive, employing numerous assistants to help with drapery, backgrounds, and copies, a common practice for successful painters of the era. While this ensured a prolific output, it sometimes led to variations in quality in works attributed to his studio. Beyond portraits, he also undertook some mythological and religious commissions in England and had ambitions to decorate the Banqueting House at Whitehall with a cycle on the history of the Order of the Garter, though this project never materialized.

Artistic Style and Representative Works

Van Dyck's style is characterized by its elegance, refinement, and psychological acuity. He had an exceptional ability to render the textures of fabrics – silks, satins, velvets, and lace – which added to the opulence of his portraits. His figures are often elongated, with graceful hands and a slightly melancholic or contemplative expression, lending them an air of aristocratic distinction. His color palettes were rich and harmonious, often employing deep crimsons, blues, and blacks, set off by luminous flesh tones.

Key Representative Works:

"Charles I at the Hunt" (c. 1635, Louvre, Paris): Perhaps his most famous portrait of the king, depicting Charles I in casual attire, standing confidently in a landscape, exuding an air of natural authority rather than formal regality.

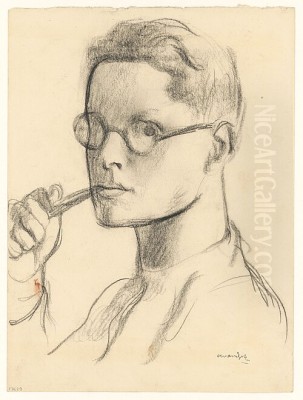

"Self-Portrait with a Sunflower" (c. 1632-33, Private Collection): A symbolic work where the sunflower, turning towards the sun (the king), represents loyalty and the artist's devotion to his royal patron.

"Marchesa Elena Grimaldi Cattaneo" (c. 1623, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.): A prime example of his Genoese period, showcasing his ability to convey grandeur and status through pose, costume, and setting.

"The Children of Charles I" (1637, Windsor Castle): A charming and dignified group portrait of the five royal children, demonstrating his skill in portraying children with both innocence and nascent regality.

"Cupid and Psyche" (c. 1639-40, Royal Collection, London): One of his most important mythological paintings from his English period, demonstrating his skill beyond portraiture.

"Samson and Delilah" (c. 1618-20, Dulwich Picture Gallery, London): An early work, showing the influence of Rubens in its dynamism and dramatic intensity, yet already hinting at Van Dyck's own emerging style.

"Portrait of Cornelis van der Geest" (c. 1620, National Gallery, London): An early portrait displaying remarkable psychological depth and technical skill, capturing the sitter's intelligence and character.

His "Iconography" (published progressively from the 1630s) was a significant project, a series of engraved portraits of famous contemporaries – artists, scholars, statesmen, and patrons. Van Dyck himself etched some of the initial plates with remarkable freedom and sensitivity, including portraits of artists like Jan Brueghel the Elder and Frans Snyders. This series not only disseminated his own fame but also created a visual record of the leading figures of his time.

Contemporaries, Collaborations, and Competition

Van Dyck's career unfolded in a rich artistic landscape. His most significant early relationship was with Peter Paul Rubens. While initially a student and assistant, Van Dyck quickly developed his own distinct style. There was mutual respect, but also an implicit rivalry as Van Dyck's talent became undeniable. Rubens's dominance in Antwerp might have been one reason Van Dyck sought opportunities abroad.

In Antwerp, Jacob Jordaens and Frans Snyders (a specialist in animal painting who sometimes collaborated with Rubens and Van Dyck) were other major figures. Jordaens became the leading painter in Antwerp after Rubens's death in 1640 and Van Dyck's permanent move to England.

During his time in Italy, Van Dyck would have been aware of the legacy of Caravaggio and the continuing influence of his dramatic naturalism, as well as the classicism of the Carracci school. He also encountered contemporary Italian artists, though his primary focus was on studying the High Renaissance masters, particularly Titian, Veronese, and Tintoretto.

In England, while Van Dyck was preeminent, other painters were active, though none could match his status. Native-born artists like William Dobson (often considered the most distinguished English-born painter before Hogarth) and Robert Walker were significantly influenced by him. Foreign artists like Daniel Mytens, whom Van Dyck largely superseded as chief court painter, were also present. The source material mentions Jan Lievens, a Dutch contemporary who also spent time in London and may have worked in Van Dyck's studio, as a competitor. Lievens, like Rembrandt, was a product of the vibrant Dutch Golden Age of painting, which also included masters like Frans Hals and Johannes Vermeer, though Vermeer's focus was on genre scenes rather than courtly portraiture.

The Spanish court painter Diego Velázquez was a contemporary whose career trajectory and specialization in royal portraiture bear some parallels with Van Dyck's, though they developed distinct national styles. Both artists were masters at conveying the power and presence of their royal patrons.

Market Performance and Enduring Legacy

Anthony van Dyck's works have always been highly prized. During his lifetime, he commanded high prices for his portraits. In the centuries since his death, his paintings have remained sought after by collectors and museums worldwide. His "Self-Portrait" (c. 1640-41), one of his last, was acquired by the National Portrait Gallery in London in 2014 after a major public fundraising campaign, underscoring his cultural significance. In 2009, another self-portrait, "Self-Portrait as a Young Man" (c. 1613-14), sold for a record £8.3 million at Sotheby's. An early work, "The Entombment," painted when he was around 17, also fetched a significant sum. A rediscovered painting, "Saint Jerome," believed to have been painted between 1615 and 1618 when Van Dyck was working alongside Rubens, sold for over $3 million in 2023. These sales highlight the continued strong market demand for his work.

His legacy is immense. In England, he effectively established the dominant tradition of portraiture that extended through the 18th century with artists like Thomas Gainsborough, Sir Joshua Reynolds, and George Romney, all of whom admired and learned from his work. His influence can also be seen in the portraiture of other European countries. He refined the art of portraiture, moving beyond mere likeness to capture the sitter's social standing, character, and an idealized sense of grace. His technical brilliance, particularly in rendering textures and his fluid brushwork, continued to inspire artists for generations. Major museums around the world, including the National Gallery in London, the Louvre in Paris, the Prado in Madrid, the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, hold significant collections of his paintings.

Anecdotes and Final Years

Van Dyck lived a lavish lifestyle in England, befitting his status. He married Mary Ruthven, a lady-in-waiting to Queen Henrietta Maria and from a Scottish noble family, in 1639. They had one daughter, Justiniana, born shortly before Van Dyck's death. Despite his success, he was reportedly often in financial difficulties due to his extravagant spending.

One anecdote mentioned in the source material concerns his tomb. Van Dyck died relatively young, at the age of 42, in London on December 9, 1641, just months after the birth of his daughter. He was buried in St. Paul's Cathedral. Tragically, his tomb and monument were destroyed in the Great Fire of London in 1666, a poignant loss of a direct physical link to one of England's most influential adopted artistic sons.

His final years were marked by declining health and perhaps a sense of unfulfilled ambition, particularly regarding large-scale historical or decorative projects. He made trips to Antwerp and Paris, possibly seeking major commissions that were not forthcoming in war-threatened England as the political situation deteriorated towards the English Civil War. Nevertheless, his output remained significant until the end.

Conclusion: Distinguishing Contributions

The name Van Dyck, therefore, carries at least two distinct artistic identities. Albert Van Dyck represents a twentieth-century artist, whose work depicting peasant life offers a glimpse into the social concerns of his era, though much about his career awaits fuller discovery. In stark contrast, Sir Anthony van Dyck stands as a towering figure of the Baroque period, a virtuoso portraitist whose elegant and insightful depictions of European aristocracy, particularly the English court of Charles I, fundamentally shaped the course of portrait painting. His technical mastery, his ability to convey both status and humanity, and his profound influence on subsequent generations of artists secure his place as one of the great masters in Western art history. While both artists named Van Dyck contributed to the vast tapestry of art, it is Anthony whose shadow looms largest and whose works continue to captivate and command admiration worldwide. Understanding their distinct historical contexts and contributions allows for a richer appreciation of the diverse paths artists take across different eras.