Sir Anthony van Dyck stands as one of the towering figures of the Flemish Baroque period, an artist whose name became synonymous with elegant portraiture and whose influence profoundly shaped the course of British art for centuries. Born on March 22, 1599, in the thriving artistic hub of Antwerp, and passing away in London on December 9, 1641, Van Dyck's relatively short life was marked by extraordinary talent, international travel, and prestigious patronage, culminating in his role as the principal court painter to King Charles I of England. His legacy extends far beyond his canvases, embedding itself in the very visual language of aristocracy and power.

Early Life and Formation in Antwerp

Anthony van Dyck was born into a prosperous family; his father was a successful silk merchant in Antwerp, providing a comfortable upbringing. His artistic talents were evident from a remarkably young age. By the age of ten, around 1609, he was already apprenticed to Hendrick van Balen, a respected Antwerp painter and a master in the local Guild of Saint Luke. Van Balen, known for his small cabinet paintings often featuring mythological scenes, provided Van Dyck with a solid foundation in the technical aspects of painting.

Even during his apprenticeship, Van Dyck's prodigious skill set him apart. By 1615, while still a teenager, he was already working as an independent painter, establishing his own workshop alongside fellow young artist Jan Brueghel the Younger. However, the most significant influence on his early development came from his association with Peter Paul Rubens, the undisputed giant of Northern European Baroque art.

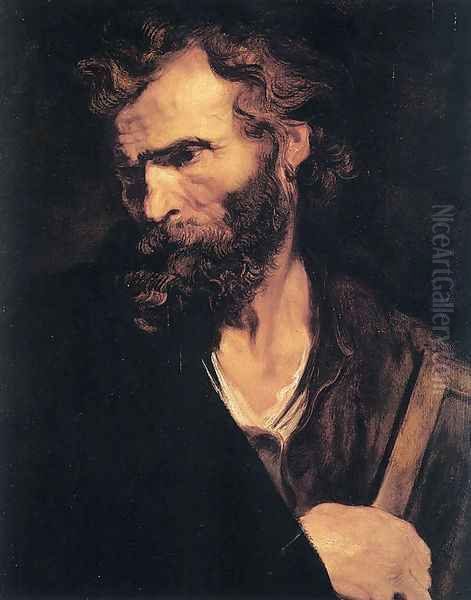

Around 1617 or 1618, Van Dyck entered Rubens's bustling Antwerp studio, not merely as a pupil but quickly rising to become his chief assistant. Rubens, recognizing the exceptional ability of his young colleague, famously referred to Van Dyck as "the best of my pupils." Working alongside Rubens exposed Van Dyck to large-scale commissions, complex compositions, and the dynamic, dramatic style that characterized Rubens's work. He assisted Rubens on major projects, learning invaluable lessons about studio management, handling patrons, and the powerful use of color and light. Works like his early Apostle Jude show his burgeoning talent and absorption of the prevailing Baroque idiom. In February 1618, Van Dyck was formally admitted to the Antwerp Guild of Saint Luke as a master in his own right.

The Italian Sojourn: Broadening Horizons

Seeking to further refine his skills and broaden his artistic horizons, Van Dyck embarked on a journey to Italy in late 1621, a trip encouraged, perhaps even facilitated, by Rubens. Italy, the cradle of the Renaissance and the heartland of classical art, was an essential destination for ambitious Northern European artists. Van Dyck spent approximately six years there, absorbing the lessons of the Italian masters and forging his own distinct artistic identity.

His longest stay was in Genoa, a wealthy port city whose aristocratic families provided ample patronage. He also traveled extensively, visiting Rome, Venice, Florence, Mantua, and Palermo. In Italy, Van Dyck immersed himself in the study of the great Renaissance and contemporary masters. He was particularly captivated by the Venetian school, especially the works of Titian, whose sophisticated use of color, elegant compositions, and insightful portrayal of sitters profoundly influenced Van Dyck's developing approach to portraiture. He also studied the works of artists like Tintoretto and Paolo Veronese.

While in Rome, he would have encountered the dramatic realism and chiaroscuro of Caravaggio and his followers, though his own style leaned more towards refinement than raw drama. During this period, Van Dyck honed his skills as a portraitist, developing a style characterized by graceful poses, luxurious textures, and a sense of relaxed authority. He painted numerous portraits of Italian nobility, such as the striking depiction of Lucas van Uffel, showcasing his growing confidence and unique blend of Flemish detail with Italianate elegance. This Italian experience was transformative, equipping him with a sophisticated visual vocabulary that would define his mature work.

Return to Flanders and the Call to England

Van Dyck returned to Antwerp in 1627, his reputation significantly enhanced by his Italian travels. He quickly established himself as a leading painter in his native city, second only to Rubens. During this second Antwerp period, he received numerous commissions for portraits and large-scale religious works, including altarpieces like The Imprisonment of Saint Sabina. His style continued to evolve, showing a greater refinement and psychological depth compared to his earlier Flemish works.

However, his success in Antwerp was soon overshadowed by an opportunity across the English Channel. Van Dyck had briefly visited England in 1620-1621, working for King James I, but the stay was short. The ascension of Charles I to the English throne in 1625 marked a new era of artistic patronage. Charles I was a passionate art collector and connoisseur, determined to elevate the status of the arts in his kingdom. Having seen Van Dyck's work, possibly through agents or examples brought to England, Charles was eager to lure the celebrated Flemish painter to his court.

In 1632, Van Dyck accepted the King's invitation and moved to London. This move marked the beginning of the final, most famous chapter of his career. England, at that time, lacked a native painter of Van Dyck's stature and sophistication, particularly in the realm of portraiture. His arrival was met with immediate acclaim and royal favor.

Principal Painter to the King: The English Zenith

Upon his arrival in London in April 1632, Van Dyck was immediately embraced by the English court. In July of that same year, King Charles I appointed him "Principal Painter in Ordinary to their Majesties" and bestowed upon him a knighthood, henceforth known as Sir Anthony van Dyck. This prestigious appointment came with a substantial annual pension of £200 and a residence provided at Blackfriars, conveniently accessible to the court via the River Thames.

Van Dyck quickly became the favored painter of the King, Queen Henrietta Maria, and the wider Stuart court aristocracy. His relationship with Charles I was particularly close; the King admired not only Van Dyck's artistic skill but also his courtly manners and sophisticated bearing. Van Dyck painted Charles I numerous times, creating iconic images that have largely defined our perception of the ill-fated monarch. These portraits were more than mere likenesses; they were carefully constructed images intended to project majesty, authority, and the divine right of kings.

Among his most celebrated royal portraits are the magnificent Charles I on Horseback, which presents the King as a commanding, almost imperial figure, and the innovative Triple Portrait of King Charles I, created to be sent to the sculptor Gian Lorenzo Bernini in Rome as a model for a bust. He also painted tender portraits of Queen Henrietta Maria and numerous group portraits of the royal children, capturing both their status and a sense of youthful innocence.

Van Dyck's studio in Blackfriars became a hub of artistic production. To meet the high demand for his portraits from the English nobility, he employed a team of assistants, following the workshop model established by Rubens. While Van Dyck would typically paint the face and hands and oversee the final composition, assistants often worked on drapery, backgrounds, and replicas. This efficient system allowed him to produce a large body of work, estimated at around 400 portraits during his English period alone, cementing his dominance over the English art scene.

The Van Dyck Style: Elegance and Influence

Sir Anthony van Dyck's name is inextricably linked with a particular style of portraiture characterized by effortless elegance, refined sensibility, and psychological acuity. He synthesized the rich textures and meticulous detail of his Flemish training with the graceful compositions and sophisticated color harmonies he absorbed in Italy, particularly from Titian. This fusion resulted in portraits that flattered his sitters while simultaneously conveying their status and personality.

He developed and popularized what became known as the "Grand Manner" in portraiture, presenting subjects life-sized, often in elaborate settings, with poses that conveyed nobility and ease. His figures possess a characteristic languid grace, often depicted with elongated fingers, tilted heads, and expressive eyes. Van Dyck had an exceptional ability to render the textures of luxurious fabrics – silks, satins, velvets – and the gleam of armor and jewels, adding to the overall impression of aristocratic refinement.

His brushwork was fluid and confident, less robust than Rubens's but possessing a delicate precision, especially in the rendering of faces and hands. His color palettes were often rich yet harmonious, contributing to the overall elegance. Beyond mere likeness, Van Dyck sought to capture the inner life or 'air' of his sitters, suggesting their character and social standing through subtle nuances of expression and pose.

The impact of the "Van Dyck style" on English portraiture was immediate and profound, lasting for over 150 years. He essentially established the visual template for aristocratic portraiture in Britain. Artists like William Dobson and Robert Walker, active during and shortly after Van Dyck's time, clearly show his influence. His successor as court painter, Sir Peter Lely, and later Sir Godfrey Kneller, continued the Van Dyckian tradition, adapting it to the tastes of subsequent eras. Even the great masters of the later 18th century, such as Sir Joshua Reynolds and Thomas Gainsborough, constantly looked back to Van Dyck as a benchmark of excellence in portraiture. Gainsborough, in particular, expressed deep admiration, famously exclaiming on his deathbed, "We are all going to Heaven, and Van Dyck is of the company." The influence can even be traced to later artists like John Singer Sargent.

Van Dyck's influence extended beyond painting techniques. He popularized a specific style of facial hair – a pointed beard combined with a moustache – which became known as the "Van Dyck beard" and enjoyed periods of fashionability for centuries. Even the pigment "Van Dyck brown," a rich, transparent earth color, bears his name, testament to his pervasive impact on the visual culture of his time and beyond.

Beyond Portraiture: Religious and Mythological Works

While best known for his portraits, Sir Anthony van Dyck was also a highly accomplished painter of religious and mythological subjects. These works, though less numerous than his portraits, particularly during his English period, demonstrate the breadth of his talent and his grounding in the grand traditions of history painting inherited from Rubens and the Italian masters.

During his early career in Antwerp and his time in Italy, religious commissions formed a significant part of his output. He created powerful altarpieces and devotional paintings characterized by dramatic compositions, emotional intensity, and skilled draughtsmanship. Examples include The Arrest of Christ, notable for its dynamic movement and use of chiaroscuro, and moving depictions of the Passion like Christ on the Cross and various versions of The Lamentation (distinct from the famous fresco by Giotto, despite some confusion in source material). His Deposition in Antwerp showcases his ability to handle complex multi-figure compositions with pathos and dignity.

Mythological themes also appeared in his work, often treated with the same elegance and refinement as his portraits. Cupid and Psyche, painted for the King's residence, is a notable example from his English period, demonstrating a softer, more lyrical approach compared to the high drama of some of his earlier religious works. Samson and Delilah, likely painted earlier, shows his capacity for depicting dramatic narrative moments, clearly influenced by Rubens but with his own distinct touch.

Furthermore, Van Dyck was an innovative printmaker, particularly skilled in etching. His Iconography was a series of engraved portraits of famous contemporaries – artists, scholars, statesmen, and patrons. Van Dyck himself etched several of the plates with remarkable freedom and psychological insight, showcasing his mastery in this medium as well. He was also proficient in watercolor, using it for sketches and studies, demonstrating a versatility that extended across various artistic media. These non-portrait works underscore his comprehensive artistic training and his ambition to excel in all the major genres of painting.

Personal Life, Rumors, and Final Years

Sir Anthony van Dyck's life in London was one of considerable success and social standing. He lived lavishly, maintaining a large house in Blackfriars and a country retreat in Eltham. His charm and courtly manners made him a popular figure in aristocratic circles. However, his personal life was not without complexity and speculation.

He was known to have had several mistresses, the most famous being Margaret Lemon, who was herself a subject of some of his paintings. Her fiery temperament reportedly led her to attempt to bite off his thumb in a fit of jealousy upon learning of his impending marriage. In 1639, perhaps encouraged by the King who may have wished his principal painter to adopt a more settled life, Van Dyck married Mary Ruthven, a Scottish noblewoman and lady-in-waiting to the Queen. This marriage connected him directly to the British aristocracy.

Despite the marriage, rumors persisted about his lifestyle. His health began to decline in his later years. Some contemporaries attributed this to overwork and a life of luxury. There were also persistent, though likely unfounded, rumors that he became obsessed with alchemy in his final years, seeking the philosopher's stone in an attempt to bolster his finances, and that this pursuit damaged his health. Another piece of society gossip linked him romantically, perhaps scandalously, with Venetia Stanley, the famously beautiful wife of the courtier Sir Kenelm Digby, both of whom Van Dyck painted. The circumstances surrounding Venetia's sudden death in 1633 led to whispers, though no concrete evidence ever implicated Van Dyck.

His marriage to Mary Ruthven produced one daughter, Justina, born just days before his death. Van Dyck fell seriously ill in late 1641 after returning from a trip to Paris, where he had hoped to secure a commission to decorate the Louvre. Despite the King sending his own physicians, Van Dyck died at his home in Blackfriars on December 9, 1641, at the age of 42. He was buried with great honor in Old St Paul's Cathedral, a testament to the high esteem in which he was held. His tomb, along with the cathedral itself, was destroyed in the Great Fire of London in 1666. His wife, Mary Ruthven, outlived him by only a few years, dying around 1645.

Legacy and Enduring Reputation

Sir Anthony van Dyck's death marked the end of a brilliant career that left an indelible mark on the history of art, particularly in Britain. His influence on portraiture was unparalleled, establishing a standard of elegance and psychological depth that dominated the genre for generations. He provided the English aristocracy with a visual identity, capturing their likenesses with a sophistication previously unseen in England.

His legacy is preserved not only through the vast number of paintings he produced but also through the enduring impact of his style. Artists for centuries studied his techniques, admired his compositions, and sought to emulate the effortless grace he imparted to his subjects. Major galleries and collections worldwide proudly display his works, including the Royal Collection, the National Gallery in London, the Prado Museum in Madrid, the Louvre in Paris, the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., and numerous others. His self-portraits, such as the famous Self-Portrait with Sunflower, continue to fascinate viewers, offering glimpses into the artist's own persona.

Though his time as court painter coincided with the growing political tensions that would soon erupt into the English Civil War, Van Dyck's art captured the specific cultural moment of the Caroline court – its refinement, its sense of privilege, and perhaps its underlying fragility. He remains a pivotal figure in the transition from the High Baroque towards a more refined, courtly aesthetic. Sir Anthony van Dyck was more than just a painter; he was a shaper of images, a master of elegance, and a crucial figure in the artistic heritage of both Flanders and Great Britain. His epitaph in Old St Paul's, reportedly chosen by the King himself, aptly summarized his impact: "He who gave life to many..." through his art.