Albert Wainwright (1898-1943) was a distinctive British artist whose life, though tragically cut short, left behind a body of work that continues to intrigue and attract attention. Working primarily in watercolour and drawing, Wainwright developed a style that, while rooted in certain British traditions, also embraced modern sensibilities. His art spanned landscapes, figurative work, and notably, theatrical design, showcasing a versatile talent that deserves wider recognition. Understanding Wainwright involves piecing together biographical details, analysing his artistic output, and placing him within the rich tapestry of early to mid-20th century British art.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in Castleford, Yorkshire, in 1898, Albert Wainwright emerged during a period of significant artistic transition in Britain and Europe. The late Victorian era was giving way to the fresh perspectives of the Edwardian period and the burgeoning movements of modernism. His formative years would have been set against a backdrop of industrial strength in Yorkshire, but also the enduring beauty of the English landscape, a dichotomy that often fuels artistic expression.

Wainwright's formal artistic training took place at the Leeds School of Art, a notable institution that also nurtured talents like Henry Moore and Barbara Hepworth around the same period. This environment would have exposed him to rigorous academic training but also to the exciting new ideas filtering in from the continent – Post-Impressionism, Fauvism, and Cubism were all making their impact felt. Following his studies at Leeds, he is also understood to have attended the Royal College of Art in London, further refining his skills and broadening his artistic horizons. The capital would have offered even greater exposure to contemporary art and a vibrant cultural scene.

The influences on a young artist during this time were manifold. The legacy of British Romantic landscape painters like J.M.W. Turner and John Constable, with their emphasis on light, atmosphere, and the sublime power of nature, was still pervasive. However, the decorative elegance of the Art Nouveau movement, with its sinuous lines and organic forms, and the emerging, more stylized language of Art Deco, would also have been part of the visual culture. Artists like Aubrey Beardsley, though from a slightly earlier generation, had left an indelible mark with their mastery of line and dramatic composition, which resonated with many younger artists exploring graphic media.

Artistic Style and Thematic Exploration

Albert Wainwright's primary medium was watercolour, often combined with ink, a combination that allowed for both fluidity and precise definition. His style is not easily pigeonholed into a single category. While the provided information mentions "classical watercolour painting, particularly the British Victorian style," this likely refers to the foundational techniques and perhaps some early influences or specific landscape works. His broader oeuvre, particularly his figure studies and designs, often displays a more modern, stylized, and decorative quality, sometimes with an Art Deco sensibility in its elegance and patterning.

His subject matter was diverse. He painted landscapes, capturing the essence of the English countryside and also scenes from his travels, which reportedly included France, Italy, and Morocco. These travel experiences undoubtedly enriched his palette and introduced new motifs into his work. Beyond landscapes, Wainwright was a keen observer of people, producing portraits and figure compositions that often possess a distinct character and charm. His line work could be delicate and sensitive, or bold and graphic, depending on the subject and desired effect.

A significant aspect of his artistic output was his involvement with theatrical design. This field allowed him to combine his skills in drawing, colour, and composition to create visually engaging sets and costumes. Theatrical work often demands a certain flair and stylization, which would have complemented his natural inclinations. This facet of his career highlights his versatility and his ability to apply his artistic vision across different creative domains.

Representative Works and Their Characteristics

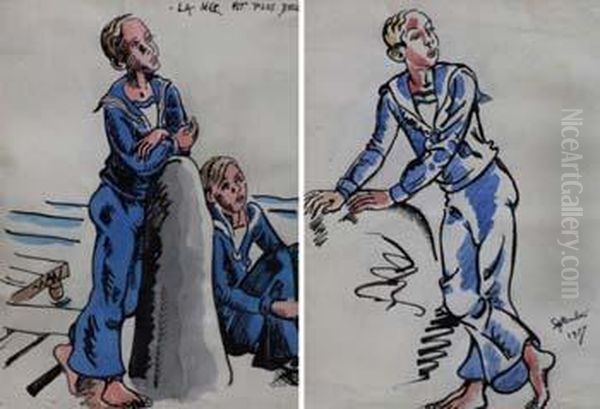

Among the works attributed to Albert Wainwright, LA MER EST PLUS BELLE ("The Sea is More Beautiful"), created in 1937, is a notable example. Executed in watercolour and ink, the title itself evokes a poetic, perhaps romantic, engagement with the subject of the sea. The use of both watercolour for its translucent washes and ink for definition would allow for a rich interplay of textures and lines, characteristic of much of his work. The date places it firmly in the interwar period, a time when British art was navigating between traditional representation and various strands of modernism.

Another piece mentioned is ACCORDING TO THE ACT. While the provided information notes it as unsigned, untitled (the given title likely being descriptive or an auction house designation), and undated, it is identified as a watercolour. The lack of signature or formal title on some works is not uncommon, especially for studies, sketches, or pieces that remained in the artist's studio. Such works often surface later and are attributed based on stylistic analysis and provenance. Without a visual, it's hard to elaborate on its specific style, but its medium aligns with Wainwright's known practice.

His landscapes, as suggested, often focused on natural elements like trees, grass, and wildflowers. This aligns with a long tradition in British art, but Wainwright's interpretation would have been filtered through his own stylistic preferences, potentially imbuing these scenes with a lyrical quality or a strong sense of design rather than purely naturalistic representation. The "typical British landscape painting characteristics" would include an appreciation for the subtleties of light and atmosphere, and a deep connection to the spirit of place.

Wainwright in the Context of British Art

To fully appreciate Albert Wainwright, it's essential to see him within the broader currents of British art during his lifetime. The early 20th century was a dynamic period. While some artists continued in established academic or Impressionistic veins, others were forging new paths. The Bloomsbury Group, with artists like Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant, were exploring Post-Impressionist ideas. Vorticism, led by Wyndham Lewis, offered a radical, machine-age aesthetic.

More directly relevant to Wainwright's likely sphere would be the artists associated with a form of modern British romanticism or those who excelled in watercolour and design. Figures like Paul Nash and his brother John Nash brought a modern sensibility to landscape painting, often imbuing it with a sense of mystery or melancholy. Eric Ravilious and Edward Bawden, who were slightly younger contemporaries, became celebrated for their distinctive work in watercolour, illustration, and design, sharing a certain Englishness and a refined graphic quality that might find echoes in Wainwright's art. Ravilious, in particular, had a unique way of capturing the chalk downlands and coastal scenes of southern England with a cool, patterned elegance.

The interwar period also saw a flourishing of printmaking and illustration, with artists finding new ways to disseminate their work. The emphasis on design was strong, and artists often moved fluidly between fine art and applied arts, much like Wainwright did with his theatrical work. This era valued craftsmanship and a distinctive personal vision. One might also consider the influence of artists who, while working in different primary media, shared a focus on expressive line, such as the sculptor and draughtsman Eric Gill.

The tradition of British watercolour painting is long and distinguished, from early topographical artists to the expressive freedom of Turner. By Wainwright's time, watercolour was a fully respected medium, capable of both intimate sketches and ambitious exhibition pieces. Artists like Philip Wilson Steer had earlier bridged Impressionism with British landscape traditions, while others continued to explore the medium's unique properties of transparency and immediacy.

The Influence of Nature on Artistic Styles: A Broader View

The provided information touches upon how natural landscapes influence artistic styles, citing various artists. This broader context helps illuminate the diverse ways artists, including potentially Wainwright, engage with nature.

For instance, the American artist George Inness, though from an earlier generation, was known for his Tonalist landscapes that emphasized mood, atmosphere, and the spiritual qualities of nature, often through subtle gradations of colour and soft light, particularly at dawn or dusk. This contrasts with the approach of John Constable, whose robust, empirical studies of English weather and countryside aimed for a more direct, though still deeply felt, representation of natural phenomena, famously capturing the movement of clouds and the sparkle of light on foliage.

The Post-Impressionists took nature in entirely different directions. Vincent van Gogh used vibrant, often non-naturalistic colour and dynamic, expressive brushstrokes to convey his intense emotional response to the landscapes of Provence, as seen in works like Starry Night or his wheatfield series. His contemporary, Paul Cézanne, sought to find the underlying geometric structure in nature, famously advising to "treat nature by the cylinder, the sphere, the cone." His methodical application of colour patches built up forms and spaces in a way that profoundly influenced Cubism and later abstract art.

In a different cultural context, the Chinese artist Shi Lu, working in the 20th century, used traditional ink painting techniques to depict the stark, powerful landscapes of Northwest China, such as in his Huashan Sketchbook, infusing them with personal and political meaning. His work shows how landscape can be a vehicle for cultural identity and historical commentary.

The Impressionists and their followers, like Édouard Manet (though more a precursor and contemporary than a strict Impressionist) and Paul Gauguin (who moved beyond Impressionism to Synthetism), also engaged with landscape, often as a setting for modern life or, in Gauguin's case, as a backdrop for symbolic and exoticized figures. Manet's plein-air paintings captured the fleeting moments of light and leisure, while Gauguin sought a more primitive and spiritual connection to nature in places like Brittany and Tahiti.

The technical mastery of J.M.W. Turner in both watercolour and oil allowed him to depict nature's most dramatic and sublime aspects – storms, seascapes, and atmospheric effects – pushing the boundaries of representation towards abstraction. His work demonstrates how an artist can convey not just the appearance of nature, but its elemental power and emotional impact.

While the provided text mentions a "Marcus Schnabel" in relation to geometric and spatial techniques, this artist is not widely recognized in major art historical canons. Perhaps it refers to a lesser-known figure or a misattribution. However, the general point about artists using geometry and spatial understanding to depict landscapes is valid, as seen in Renaissance perspective or Cézanne's structural approach.

These diverse examples illustrate that "nature" is not a monolithic subject but a vast source of inspiration that artists interpret through their individual temperaments, cultural contexts, and stylistic choices. Wainwright, working with the English landscape and scenes from his travels, would have similarly filtered his observations through his own artistic lens, likely emphasizing design, pattern, and perhaps a certain lyrical or narrative quality.

Challenges in Documentation and Legacy

The information provided hints at gaps in the readily available information about Albert Wainwright, such as specific details about his birthplace, place of death (though research confirms his death in Morocco on active service in 1943), and a comprehensive list of career achievements or anecdotes. This is not unusual for artists who may not have achieved widespread fame during their lifetime or whose careers were cut short. World War II, during which Wainwright died, also caused significant disruption and loss of records.

His death at the relatively young age of 44 or 45 meant his artistic development was curtailed. We are left to speculate on how his style might have evolved had he lived longer. However, the works that do survive, and their appearance in auction catalogues like the one referenced (Bonhams, "Modern British and Irish Art," 20 May 2024, for LA MER EST PLUS BELLE and ACCORDING TO THE ACT), indicate an ongoing interest in his art. Such sales can bring an artist's work to new audiences and prompt further research.

The legacy of an artist like Wainwright often builds gradually. It relies on dedicated research by art historians, curation by galleries, and interest from collectors. His connection to institutions like Leeds School of Art and the Royal College of Art, and his contemporaneity with major figures in British modernism, provide fertile ground for reassessment. His work in theatrical design also offers a specific avenue for study, connecting him to the history of British theatre in the interwar period.

Conclusion: The Enduring Vision of Albert Wainwright

Albert Wainwright stands as a fascinating figure in early to mid-20th century British art. A skilled watercolourist and draughtsman, he navigated the artistic currents of his time, producing work that encompassed landscapes, figurative subjects, and theatrical designs. His art, characterized by a blend of traditional technique and modern sensibility, often reveals a strong sense of design, an elegant line, and a nuanced use of colour.

While not as widely known as some of his contemporaries like Henry Moore or Barbara Hepworth from his Leeds days, or design luminaries like Eric Ravilious, Wainwright's contribution is nonetheless valuable. His works, such as LA MER EST PLUS BELLE, offer glimpses into a distinct artistic personality. The very act of rediscovering and re-evaluating artists like Wainwright enriches our understanding of the period, revealing the diversity of talent that flourished beyond the headline names.

His engagement with the British landscape tradition, filtered through a more modern, sometimes decorative style, and his versatility across different artistic applications, mark him as an artist of substance. As more of his work comes to light and receives scholarly attention, Albert Wainwright's place in the story of British art will undoubtedly become clearer and more appreciated, a testament to a talent that captured the beauty and character of his world with a unique and enduring vision. His life, tragically shortened by war, reminds us of the preciousness of artistic creation and the importance of preserving and understanding the legacies of all who contribute to our cultural heritage.