Alfred William Hunt stands as a distinguished figure in the annals of British art, particularly celebrated for his mastery of watercolour and his evocative landscape paintings. Active during the vibrant and transformative Victorian era, Hunt carved a unique niche for himself, blending meticulous observation with a poetic sensibility. His works, often imbued with a quiet reverence for nature, reflect the prevailing artistic currents of his time, notably the influence of John Ruskin and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, while also echoing the grandeur of earlier masters like J.M.W. Turner. This exploration delves into the life, art, and enduring impact of a painter whose dedication to his craft left an indelible mark on the British landscape tradition.

Early Life and Formative Influences

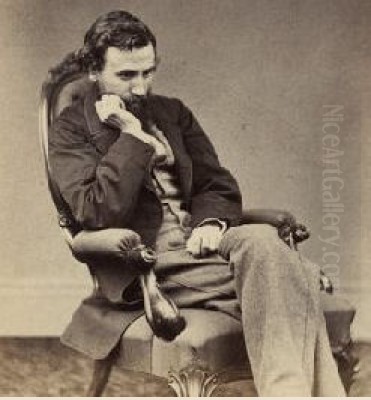

Alfred William Hunt was born in Liverpool on November 15, 1830. His father, Andrew Hunt, was himself a landscape painter and drawing master, providing young Alfred with an immediate and immersive introduction to the world of art. Growing up in a household where artistic pursuits were valued and practiced undoubtedly shaped his early inclinations. Liverpool, a bustling port city, would have offered a dynamic backdrop, though it was the natural world, rather than the urban environment, that would ultimately captivate his artistic imagination.

His early education was undertaken at the Liverpool Collegiate School (some sources mention Liverpool St. John's College, but the Collegiate is more frequently cited for his pre-Oxford schooling). Here, he would have received a solid grounding in classical subjects, a common educational path for young men of his standing. This academic foundation was not incidental to his later artistic career; it fostered a disciplined mind and an appreciation for intellectual pursuits that would complement his artistic talents. The environment of Liverpool, with its growing industrial might and its proximity to the varied landscapes of Northern England and Wales, likely provided early visual stimuli.

The direct influence of his father, Andrew Hunt, cannot be overstated. From a young age, Alfred would have observed his father's techniques, his approach to capturing landscapes, and the practicalities of an artist's life. This familial apprenticeship provided a crucial foundation, instilling in him the fundamental skills of drawing and painting. It was a common practice for artists to emerge from such backgrounds, where skills were passed down through generations, creating artistic dynasties, albeit sometimes modest ones.

Beyond his father, another significant early influence was David Cox, a prominent landscape painter and a friend of Andrew Hunt. Cox was renowned for his vigorous and atmospheric watercolours, particularly his depictions of Welsh scenery. Exposure to Cox's work, and perhaps even personal interactions, would have demonstrated the expressive potential of watercolour, a medium that Alfred William Hunt would come to master with exceptional finesse. Cox's ability to convey the changing moods of nature and the effects of weather likely resonated with the young Hunt.

The Call of Art and Academic Pursuits

Despite his evident artistic talent and early immersion in painting, Hunt's path was not initially set solely on an artistic career. In 1848, he matriculated at Corpus Christi College, Oxford, to read Classics. This decision reflects a duality that would characterize his early adult life: a commitment to scholarly achievement alongside a burgeoning passion for art. Oxford, with its rich history and intellectual rigor, provided a stimulating environment.

During his time at Oxford, Hunt excelled academically. He won the prestigious Newdigate Prize for English Verse in 1851 for his poem "Nineveh." This achievement underscores his literary talents and his capacity for creative expression beyond the visual arts. His classical studies would have deepened his understanding of mythology, history, and literature, themes that often subtly informed the intellectual undercurrents of Victorian art. He graduated with a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1852 and was subsequently elected a Fellow of Corpus Christi College in 1853, a testament to his scholarly prowess. He later received his Master of Arts degree.

Even amidst his academic responsibilities as a Fellow, Hunt continued to paint. He began exhibiting his works, initially in Liverpool. His first major public showing was at the Liverpool Academy of Arts in 1847, even before his Oxford years. He became an associate of the Liverpool Academy in 1850 and a full member in 1854. This early recognition within his native city's art scene was an important encouragement.

The tension between an academic career and a life devoted to art eventually reached a tipping point. Encouraged by the renowned art critic John Ruskin, who saw great promise in his work, Hunt made the decisive choice to dedicate himself fully to painting. He resigned his Oxford fellowship in 1861, a significant step that marked his full commitment to the precarious but compelling life of an artist. This decision was not taken lightly, as an Oxford fellowship offered security and status, contrasting with the often uncertain prospects of a professional painter.

The Ruskinian Imprint: Truth to Nature

No discussion of Alfred William Hunt's artistic development would be complete without acknowledging the profound influence of John Ruskin. Ruskin, the pre-eminent art critic of the Victorian era, championed a philosophy of "Truth to Nature," urging artists to observe and record the natural world with meticulous accuracy and heartfelt reverence. His writings, particularly "Modern Painters," had a seismic impact on a generation of artists, including Hunt.

Hunt first encountered Ruskin's ideas during his formative years, and they resonated deeply with his own inclinations towards detailed observation. Ruskin admired Hunt's work, recognizing in it the qualities he espoused: careful delineation of form, sensitivity to atmospheric effects, and an honest engagement with the subject matter. He became a mentor and a patron to Hunt, offering guidance and encouragement.

Ruskin's philosophy extended beyond mere verisimilitude. He believed that close study of nature could reveal divine truths and that art had a moral purpose. This imbued landscape painting with a new seriousness and significance. For Hunt, this meant approaching his subjects – whether the rugged mountains of Wales, the serene lakes of Scotland, or the coastal vistas of England – with a sense of profound respect and a desire to capture their essential character.

The critic's influence was not merely theoretical. Ruskin actively supported Hunt, recommending his work to collectors and even inviting him on sketching tours. For instance, a trip to Switzerland and Italy in 1872 with Ruskin provided Hunt with invaluable opportunities to study diverse landscapes and to benefit from Ruskin's direct tutelage. This close association with Ruskin helped to shape Hunt's artistic vision and to solidify his commitment to a detailed, yet poetic, naturalism. Artists like John Brett and J.W. Inchbold were also profoundly affected by Ruskin's call for geological and botanical accuracy in landscape painting.

The Pre-Raphaelite Connection

Alfred William Hunt's art also shows a strong affinity with the principles of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB), though he was not a formal member of the original group founded by William Holman Hunt (no relation), John Everett Millais, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti. The PRB, formed in 1848, rebelled against the Royal Academy's prevailing academic conventions, which they felt were formulaic and artificial, advocating instead for a return to the detailed realism and vibrant colour of art before Raphael.

Hunt shared the Pre-Raphaelites' emphasis on meticulous detail, bright, clear colours, and direct observation from nature. His landscapes often exhibit an almost photographic clarity in their rendering of foliage, rock formations, and water surfaces. This commitment to empirical study aligned perfectly with Ruskin's "Truth to Nature" and with the scientific spirit of the Victorian age. Like the Pre-Raphaelites, Hunt often spent considerable time sketching outdoors, directly engaging with his subjects to capture their nuances.

While the PRB is often associated with figural compositions laden with literary or symbolic meaning, their influence extended to landscape painting. Artists like Ford Madox Brown, closely associated with the PRB, also produced highly detailed landscapes. Hunt's work can be seen as part of this broader movement towards a more intense and faithful representation of the natural world. His detailed foregrounds, a hallmark of Pre-Raphaelite landscape, invite the viewer to scrutinize every leaf and pebble.

His connection to the Pre-Raphaelite circle was also personal. His wife, Margaret Raine Hunt, was a novelist and translator, and their home became a gathering place for artists and writers, including those associated with the Pre-Raphaelite movement. Their daughter, Violet Hunt, also a writer, grew up in this intellectually and artistically stimulating environment, further cementing the family's ties to this influential artistic current.

Mastery in Watercolour: Technique and Vision

Alfred William Hunt is primarily celebrated as a watercolourist, a medium in which he achieved extraordinary subtlety and brilliance. British watercolour painting had a distinguished tradition, with artists like Thomas Girtin and J.M.W. Turner elevating it to a major art form. Hunt built upon this legacy, developing a technique that combined meticulous precision with a remarkable sensitivity to light and atmosphere.

His watercolours are characterized by their delicate washes, intricate detail, and luminous colour. He often employed a technique of layering transparent washes to build up depth and luminosity, allowing the white of the paper to shine through and contribute to the overall radiance of the image. This method, combined with fine brushwork for details, enabled him to capture the most subtle gradations of tone and colour, from the hazy mists of a Scottish loch to the sun-dappled foliage of an English woodland.

Hunt's handling of light was particularly masterful. He was adept at depicting the varied effects of sunlight, shadow, and atmospheric conditions, lending his scenes a palpable sense of time and place. Whether it was the clear, crisp light of a summer morning or the soft, diffused light of an overcast day, he conveyed these nuances with remarkable fidelity. This sensitivity to atmospheric phenomena links him to Turner, whom he greatly admired, though Hunt's approach was generally more restrained and less overtly dramatic than Turner's later, more abstract works.

He was also skilled in oil painting, and his oil works share the same commitment to detailed realism and atmospheric truth. However, it is in watercolour that his distinctive genius found its fullest expression. He was a prominent member of the Society of Painters in Water Colours (often known as the "Old Watercolour Society"), being elected an Associate in 1862 and a full Member in 1864. His contributions helped to maintain the high standards and prestige of this institution. Other notable watercolourists of the era included Myles Birket Foster, known for his charming rural scenes, and Helen Allingham, who also specialized in detailed depictions of cottage life and gardens, though Hunt's focus was more on the grandeur and wildness of nature.

Key Themes and Subjects

The landscapes of Great Britain provided the primary inspiration for Alfred William Hunt. He travelled extensively throughout England, Scotland, and Wales, seeking out picturesque and sublime scenery. His subjects ranged from tranquil river valleys and coastal scenes to rugged mountains and dramatic seascapes.

The North of England, particularly the Lake District and the coastline of Northumberland (such as his famous depictions of Bamburgh and Dunstanburgh), held a special appeal for him. He captured the unique character of these regions with great sensitivity, paying close attention to their geological formations, flora, and changing weather patterns. His paintings of Durham, where he lived for a period after 1861, are also notable, showcasing the city's dramatic cathedral and castle perched above the River Wear.

Wales was another favourite sketching ground, its mountainous terrain offering the kind of sublime scenery that fascinated Romantic and Victorian artists. Works like "Autumn Northwales" exemplify his ability to convey the grandeur of these landscapes, often imbued with a sense of solitude and timelessness. Similarly, the Scottish Highlands, with their lochs and misty peaks, provided ample material for his brush. "Morning Mist on Loch Maree" is a testament to his skill in capturing the ethereal beauty of such scenes.

While wild, untamed nature was a dominant theme, Hunt also painted more pastoral subjects, including river scenes along the Thames, such as those around Sonning. These works often possess a gentle, lyrical quality, reflecting a quieter aspect of the British landscape. In all his subjects, there is a consistent sense of deep engagement with the natural world, a desire to understand and interpret its myriad forms and moods. His approach was less about imposing an artistic vision onto nature and more about revealing the beauty and complexity inherent within it, a philosophy that aligns with the earlier devotion to nature seen in the works of John Constable.

Notable Works: A Closer Look

Several paintings stand out as representative of Alfred William Hunt's oeuvre, showcasing his technical skill and artistic vision. While a comprehensive list is extensive, a few key examples highlight his strengths.

"Windsor Castle" (1889), now in the Tate collection, is a fine example of his mature style. This watercolour depicts the iconic castle from a distance, bathed in a soft, atmospheric light. The meticulous rendering of the architecture is balanced by the fluid handling of the sky and the surrounding landscape, creating a harmonious and evocative image. The play of light on the water and the subtle gradations of colour in the sky demonstrate his mastery of the medium.

"Durham" (c.1862-65), also in the Tate, captures the dramatic silhouette of Durham Cathedral and Castle against a luminous sky. The work is notable for its intricate detail, particularly in the depiction of the city's architecture and the textures of the riverbanks. It conveys a strong sense of place and atmosphere, reflecting Hunt's deep appreciation for the historic city where he resided for several years.

"Loch Maree, Sunset" (exhibited 1872) would have showcased his ability to capture the dramatic effects of light and colour in the Scottish Highlands. While the specific work might be in a private collection, his depictions of Scottish lochs are generally characterized by their atmospheric depth and the subtle interplay of light on water and mountains, often conveying a sense of serene grandeur.

"Whitchurch Mill" (1896) and "Sonnings Bridge" (1896) are later works, mentioned in the provided information, likely depicting scenes along the Thames. These would demonstrate his continued dedication to capturing the tranquil beauty of the English countryside, rendered with his characteristic delicacy and precision in watercolour. The late date of these works indicates his sustained artistic activity until the end of his life.

Other significant titles include "Debatable Ground (Between England and Scotland)", which suggests a landscape imbued with historical resonance, and "Wind and Flow", a title that evokes the dynamic forces of nature that he so skillfully portrayed. Each work, whether a grand mountain vista or a quiet riverside scene, reflects his unwavering commitment to "Truth to Nature."

Exhibitions and Recognition

Alfred William Hunt was a regular exhibitor at the major London art institutions throughout his career. He showed works at the Royal Academy from 1854, contributing nearly annually for many years. His submissions to the Royal Academy were crucial for establishing his reputation, as it was the premier venue for artists to gain critical attention and patronage.

His most consistent and significant contributions, however, were to the exhibitions of the Society of Painters in Water Colours (the Old Watercolour Society). After his election as an Associate in 1862 and a full Member in 1864, he became one of its most respected exhibitors. The Society's exhibitions were vital for watercolourists, providing a dedicated platform to showcase the unique qualities of the medium. Hunt's refined and highly finished watercolours were well-suited to these exhibitions and helped to elevate the status of watercolour painting.

Beyond London, his work was also seen in provincial exhibitions, including those in his native Liverpool. International recognition came with the inclusion of his paintings in major overseas exhibitions. Notably, his work was exhibited at the Paris Universal Exposition of 1878 and the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893. These international showings helped to introduce his art to a wider audience and contributed to the growing appreciation of British landscape painting abroad.

Despite his consistent exhibition record and the admiration of critics like Ruskin, Hunt did not achieve the same level of widespread fame or financial success as some of his contemporaries, such as Frederic Leighton or Lawrence Alma-Tadema, who specialized in more popular, often classical or historical, subjects. Hunt's dedication to landscape, particularly in watercolour, appealed to a more discerning, though perhaps smaller, circle of connoisseurs and fellow artists.

Personal Life and Artistic Circle

In 1861, Alfred William Hunt married Margaret Raine (1831–1912), the daughter of James Raine, a noted antiquarian and librarian of Durham Cathedral. This marriage coincided with his decision to resign his Oxford fellowship and move to Durham, where Margaret's family had strong connections. Margaret Hunt was a formidable intellectual in her own right, a successful novelist (writing as Averil Beaumont) and a respected translator, particularly known for her English editions of Grimm's Fairy Tales.

Their marriage appears to have been a supportive partnership, though some accounts suggest that the responsibilities of family life, and perhaps Margaret's own literary career, may have at times competed for Hunt's artistic focus. One piece of information from the prompt suggests he "abandoned painting" shortly after marriage due to poverty, but this seems to contradict his continued exhibition record and election to the Old Watercolour Society in 1862. It is more likely that he faced financial struggles common to many artists, and perhaps a temporary reduction in output, rather than a complete abandonment of his career.

The Hunts later moved to London in 1865, settling at 1 Tor Villas (later renamed Tor-Court, Campden Hill), a home that became a lively center for artistic and literary society. They had three daughters: Violet, Venice, and Silvia. Violet Hunt (1862–1942) became a well-known novelist and literary hostess, associated with modernist writers like Ford Madox Ford and Ezra Pound. Her upbringing in a household frequented by artists and intellectuals, including figures from the Pre-Raphaelite circle, profoundly shaped her own creative path.

Alfred William Hunt maintained connections with many artists and writers of his day. His correspondence with the influential art dealer Ernest Gambart indicates his engagement with the commercial aspects of the art world. His circle would have included fellow members of the Old Watercolour Society and artists who shared his Ruskinian or Pre-Raphaelite sympathies. The atmosphere at Tor Villas was one of intellectual ferment and artistic exchange, reflecting the vibrant cultural life of Victorian London.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

Alfred William Hunt continued to paint and exhibit into his later years, maintaining his commitment to the detailed and atmospheric depiction of landscape. His health, however, began to decline in the 1890s. He suffered from asthma, a condition that would have made the rigours of outdoor sketching increasingly challenging. Despite this, he remained dedicated to his art.

He passed away on May 3, 1896, in London, at his home on Campden Hill. His death marked the loss of one of the most distinguished watercolourists of his generation. Memorial exhibitions of his work were held, affirming his significant contribution to British art.

Hunt's legacy lies in his exquisite body of work, which exemplifies the highest achievements of Victorian landscape painting in watercolour. He successfully synthesized the detailed naturalism advocated by Ruskin and the Pre-Raphaelites with a poetic sensitivity to light and atmosphere that echoed the Romanticism of Turner. His paintings are not merely topographical records but deeply felt responses to the beauty and grandeur of the natural world.

He influenced subsequent generations of watercolourists through his technical mastery and his unwavering dedication to capturing the truth of nature. While perhaps not as revolutionary as Turner or as populist as some of his contemporaries, Hunt's art possesses an enduring quality of quiet integrity and refined beauty. His works continue to be admired for their meticulous craftsmanship, their luminous colour, and their evocative portrayal of the British landscape. Artists like Thomas Matthews Rooke, who also worked with Ruskin and shared a similar attention to detail, can be seen as part of this lineage.

Alfred William Hunt in the Annals of Art History

In the broader context of art history, Alfred William Hunt is recognized as a key figure in the later phase of the British watercolour tradition and an important exponent of Ruskinian naturalism. His career spanned a period of significant change in the art world, from the ascendancy of Pre-Raphaelitism to the stirrings of Impressionism and modern art. While Hunt remained largely committed to the principles of detailed realism, his sensitivity to light and atmosphere can be seen as sharing some common ground with the Impressionists' concern for capturing fleeting visual effects, even if his methods and aims differed.

His work provides a valuable link between the Romantic landscape tradition of the early 19th century, exemplified by artists like Turner and Constable, and the later Victorian approach to nature. He absorbed the lessons of these earlier masters but forged a distinctive style that reflected the intellectual and aesthetic currents of his own time. The comparison to George Grosz, mentioned in the provided text, seems anachronistic and stylistically incongruous, likely a misattribution or a very broad contextualization beyond direct artistic lineage or influence. Hunt's sphere of influence and comparison lies firmly within the 19th-century British landscape school.

Today, Alfred William Hunt's paintings are held in major public collections, including the Tate Britain, the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, and numerous provincial galleries across the UK. His work continues to attract scholarly attention and is appreciated by collectors and art enthusiasts for its technical brilliance and its serene, contemplative beauty. He remains a testament to the enduring power of landscape painting and the unique expressive potential of the watercolour medium, a quiet master whose luminous visions of nature continue to resonate. His dedication to his craft, his intellectual depth, and his profound love for the landscapes he depicted secure his place as a significant and respected artist in the rich tapestry of British art.