Alessandro Bonvicino, more famously known by his moniker Moretto da Brescia (c. 1498 – 1554), stands as one of the most significant painters of the Italian High Renaissance, particularly within the vibrant artistic milieu of Brescia in Lombardy. His oeuvre, predominantly consisting of religious altarpieces and devotional paintings, alongside a distinguished body of portraiture, masterfully synthesized the rich colorism of the Venetian school with the grounded realism characteristic of Lombard art. Moretto's work is celebrated for its serene dignity, subtle psychological depth, and a distinctive use of cool, silvery tonalities that set him apart from many of his contemporaries.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born around 1498 in Rovato, a small town near Brescia, Alessandro Bonvicino's early life is somewhat shrouded in obscurity, a common fate for many artists of his era. His nickname, "Il Moretto," translates to "the little Moor" or "the dark one." The precise origin of this sobriquet remains a subject of speculation among scholars. Some suggest it might have referred to his physical appearance, perhaps a darker complexion or hair, while others posit it could have been a family name or a reference to a shop sign. Regardless of its etymology, it is the name by which he achieved enduring fame.

The details of Moretto's artistic apprenticeship are not definitively documented, leading to scholarly debate. Early sources and stylistic analysis suggest he may have initially trained under Fioravante Ferramola, a local Brescian painter of some repute. Another potential early master is Vincenzo Foppa, a foundational figure of the Lombard school whose emphasis on naturalism and sober piety would have provided a strong local tradition for Moretto to absorb. Foppa's influence, particularly his restrained palette and attention to human emotion, can be discerned in the gravitas of Moretto's early works.

There has also been considerable discussion regarding a possible period of study in Venice, perhaps even under the tutelage of the great Titian (Tiziano Vecellio). While direct documentary evidence for such an apprenticeship is lacking, the profound impact of Venetian art, especially Titian's command of color and compositional grandeur, is undeniable in Moretto's mature style. It is more likely that Moretto absorbed Venetian influences through visits to the city, exposure to Venetian paintings in Brescia, and interactions with Venetian-trained artists, rather than a formal apprenticeship with Titian himself.

Influences and the Brescian Artistic Milieu

Moretto's artistic development was shaped by a confluence of influences. The Lombard tradition, with its roots in the meticulous naturalism of artists like Vincenzo Foppa and later exemplified by figures such as Bramantino (Bartolomeo Suardi), provided a foundation of realism and a certain austerity. This was characterized by careful observation, a tendency towards sculptural form, and often a subdued emotional tenor.

However, Brescia's geographical and cultural proximity to Venice meant that the opulent colorism and dynamic compositions of the Venetian school, spearheaded by masters like Giovanni Bellini, Giorgione (Giorgio Barbarelli da Castelfranco), and preeminently Titian, exerted a powerful pull. Moretto skillfully assimilated these Venetian elements, particularly their rich palettes, atmospheric effects, and sophisticated handling of light, into his Lombard artistic vocabulary. He developed a unique synthesis, tempering Venetian sensuousness with Lombard sobriety.

Another significant contemporary and, at times, collaborator in Brescia was Girolamo Romanino (c. 1484/1487 – c. 1560). Romanino, also deeply influenced by Venetian art, particularly the work of Giorgione and the young Titian, often displayed a more rustic energy and dramatic intensity in his paintings compared to Moretto's characteristic serenity. Their careers frequently intersected, and they sometimes worked on similar commissions, offering a fascinating counterpoint in Brescian art. Lorenzo Lotto (c. 1480 – 1556/57), a Venetian painter who worked extensively in Lombardy, including Bergamo and Brescia, also played a role in the regional artistic exchange. Lotto's idiosyncratic style, marked by psychological acuity, unconventional compositions, and vibrant color, likely resonated with Moretto, particularly in the realm of portraiture and expressive religious scenes.

The artistic environment of Brescia in the early to mid-16th century was thus a fertile ground, benefiting from its Lombard heritage while being open to the powerful artistic currents emanating from Venice. This allowed painters like Moretto and Romanino to forge distinctive styles that contributed significantly to the broader tapestry of the Italian Renaissance. Other North Italian artists whose work formed part of this regional dialogue include Giovanni Gerolamo Savoldo, another Brescian active around the same time, known for his evocative nocturnal scenes and robust realism, and Palma Vecchio (Jacopo Negretti), a Venetian painter whose rich colors and idealized figures were part of the broader Venetian influence.

Religious Paintings: Piety and Palette

The vast majority of Moretto da Brescia's output consisted of religious paintings, primarily large-scale altarpieces for churches in Brescia and the surrounding Lombard and Venetian territories, as well as smaller devotional works for private patrons. His religious art is characterized by a profound sense of piety, a calm and dignified solemnity, and an often innovative approach to traditional iconography.

Moretto's figures, typically draped in voluminous, richly textured robes, possess a quiet grace and often a gentle melancholy. He excelled in depicting serene Madonnas, noble saints, and poignant scenes from the life of Christ. His color palette is distinctive, often favoring cool, silvery tones, particularly in his use of grays, blues, and muted greens, which he masterfully contrasted with passages of warmer hues like deep reds and golds. This created a harmonious and often ethereal effect, enhancing the spiritual atmosphere of his compositions. The play of light and shadow in his works is subtle yet effective, modeling forms with a soft plasticity and contributing to the overall mood.

One of his early masterpieces is the "Assumption of the Virgin" (1524-1526) for the Duomo Vecchio (Old Cathedral) in Brescia. This work already showcases his ability to handle complex multi-figure compositions with clarity and to imbue the scene with a sense of divine majesty. The apostles below gaze upwards with varied expressions of awe and wonder, while the Virgin is borne aloft by angels in a luminous cloud.

The "Saint Justina with a Donor" (also known as "St. Justina of Padua with a Kneeling Donor," c. 1530), now in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, is another iconic work. St. Justina stands majestically, her form rendered with elegant simplicity, while the donor, often identified as a member of the Martinengo family, kneels in pious devotion. The unicorn, a symbol of purity, rests at her feet. The painting is notable for its refined color harmony, the psychological connection between the figures, and the serene landscape background.

Moretto's engagement with the religious currents of his time, including the nascent stirrings of the Counter-Reformation, is evident in the clarity and devotional intensity of his works. His paintings often aimed to inspire piety and contemplation, presenting sacred figures and narratives in a manner that was both accessible and spiritually uplifting. For example, his "Supper at Emmaus" (c. 1526), housed in the Pinacoteca Tosio Martinengo, Brescia, captures the revelatory moment with a quiet intensity, focusing on the disciples' dawning recognition of the risen Christ. The everyday setting and the naturalistic depiction of the figures make the sacred event relatable.

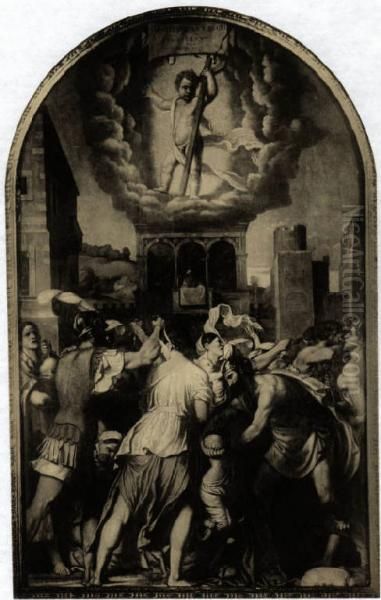

Another powerful example of his religious art is "The Massacre of the Innocents" (c. 1531-1532), painted for the church of San Giovanni Evangelista in Brescia. While the subject is inherently violent, Moretto handles it with a degree of restraint, focusing on the pathos and tragedy of the event. The composition is dynamic, yet the figures retain a certain sculptural dignity even in their distress. His ability to convey deep emotion without resorting to excessive melodrama is a hallmark of his style.

Throughout his career, Moretto produced numerous altarpieces depicting the Madonna and Child enthroned with saints, a common theme in Renaissance art. Works like the "Madonna and Child with Saints Roch and Sebastian" or the "Enthroned Madonna and Child with Saint James Major and Saint Jerome" (c. 1517, for Santa Maria delle Grazie, Brescia, now in the National Gallery, London) demonstrate his consistent ability to create balanced, harmonious compositions imbued with a gentle, devotional spirit. The saints are often individualized, their expressions conveying their specific attributes and spiritual significance.

Innovations in Portraiture

Beyond his extensive work in religious painting, Moretto da Brescia was a highly accomplished and innovative portraitist. He is considered one of the pioneers of the independent full-length portrait in Italy, a format that lent an unprecedented sense of presence and dignity to the sitter. His portraits are characterized by their psychological insight, their sober yet elegant presentation, and their often muted, sophisticated color schemes.

Moretto's sitters, typically members of the Brescian aristocracy and gentry, are depicted with a keen eye for individual character. He moved beyond mere likeness to capture a sense of the sitter's inner life and social standing. His portraits often feature a restrained palette, with blacks, grays, and whites predominating, accented by touches of color in details like a sash, a piece of jewelry, or a background element. This emphasis on tonal values contributed to the gravitas and refinement of his portraits.

A notable example is the "Portrait of a Young Man" (c. 1526), housed in the National Gallery, London. The subject, whose identity remains unknown, is presented with a quiet confidence, his gaze direct and engaging. The predominantly dark attire is rendered with subtle variations in texture, and the face is modeled with a delicate play of light and shadow. The overall impression is one of thoughtful introspection.

Another significant portrait is the "Portrait of a Gentleman" (c. 1520-1525), also in the National Gallery, London, sometimes identified as Conte Sciarra Martinengo Cesaresco. The figure stands confidently, his hand resting on his sword, a symbol of his noble status. The rich, dark costume and the serious demeanor convey an air of authority and self-possession.

Moretto's approach to portraiture was influential, particularly on his most famous pupil, Giovanni Battista Moroni (c. 1520/24 – 1579/80). Moroni would further develop the naturalistic and psychologically penetrating style of portraiture he learned from Moretto, becoming one of the leading portrait painters of the later 16th century. Moretto's ability to combine realistic depiction with a sense of aristocratic reserve set a standard for North Italian portraiture. His portraits can be compared to those of other great Renaissance portraitists like Raphael (Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino), whose portraits often conveyed an idealized grace, or Titian, whose portraits were known for their commanding presence and rich color. Moretto's style offered a distinct Lombard alternative, emphasizing a more introspective and subtly characterized realism.

Collaborations and Workshop

Like many prominent artists of his time, Moretto likely maintained an active workshop to assist with the numerous commissions he received. The scale of many of his altarpieces would have necessitated the help of assistants for tasks such as preparing panels, grinding pigments, and painting less critical areas.

His collaboration with Girolamo Romanino is particularly noteworthy. While their styles differed, they occasionally worked together on decorative schemes. For instance, they both contributed to the decoration of the Cappella del Sacramento (Chapel of the Sacrament) in the church of San Giovanni Evangelista in Brescia, though they worked on separate canvases. Their presence in the same city and their frequent competition for similar commissions created a dynamic artistic environment.

Moretto also collaborated with Floriano Ferramola, his presumed early master, on projects such as the organ shutters for the Duomo Vecchio in Brescia around 1518. He also worked alongside Lorenzo Lotto on the ambitious decorative project for the choir stalls of Santa Maria Maggiore in Bergamo, although Lotto was the principal artist for the intarsia designs. These interactions highlight the interconnectedness of the artistic community in Lombardy and the Veneto.

The most significant figure to emerge from Moretto's workshop was Giovanni Battista Moroni. Moroni absorbed Moretto's meticulous technique, his interest in naturalism, and his sophisticated use of color, particularly the silvery grays and blacks that became a hallmark of Moroni's own celebrated portraits. Moroni's later work, while developing its own distinct character, clearly bears the imprint of his master's teachings.

Later Career and Mature Style

Moretto's mature style, from the 1530s until his death in 1554, saw a consolidation of his artistic strengths. His religious paintings continued to display a profound spirituality, often with an increased emphasis on emotional expression and dramatic lighting, perhaps reflecting the growing influence of the Counter-Reformation's call for art that could move the faithful.

Works from this period, such as the "Christ in the Wilderness Served by Angels" (c. 1540s) or the "Pietà" (c. 1540s) in the Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan, showcase his mastery of composition, his ability to convey deep pathos, and his refined color sense. His figures often possess a sculptural solidity, yet are imbued with a gentle humanity. The "Adoration of the Shepherds with Saints Nazarius and Celsus" (c. 1540), painted for the church of Santi Nazaro e Celso in Brescia, is a masterful example of his late style, combining a tender depiction of the Nativity with dignified portrayals of the patron saints.

His portraits from this period also maintained a high level of quality, continuing to explore the personalities of his sitters with subtlety and insight. He remained active primarily in Brescia and its territories, though his reputation extended further, and his works were sought after by patrons in other parts of Northern Italy. The influence of Leonardo da Vinci, particularly his sfumato and psychological depth, can be seen as a broader Lombard legacy that Moretto, in his own way, continued. Similarly, the grandeur of High Renaissance masters like Andrea Mantegna, who had worked extensively in nearby Mantua, formed part of the artistic heritage of the region.

Legacy and Influence

Moretto da Brescia died in December 1554, leaving behind a substantial body of work that secured his place as one of the leading painters of the Brescian school. His unique fusion of Lombard realism and Venetian colorism created a style that was both dignified and deeply human. His religious paintings, with their serene piety and harmonious compositions, served the devotional needs of his community and contributed to the visual culture of the Counter-Reformation.

His most direct and significant legacy was through his pupil, Giovanni Battista Moroni, who became a preeminent portraitist, carrying forward Moretto's emphasis on naturalism and psychological depth. Through Moroni, Moretto's influence extended into the later 16th century.

Moretto's art, while perhaps not as widely known internationally as that of some of his Venetian contemporaries like Titian or Paolo Veronese, holds a crucial place in the history of North Italian painting. His ability to create works of profound spiritual resonance, combined with his technical skill and innovative approach to portraiture, marks him as a master of his time. His paintings continue to be admired for their quiet beauty, their refined elegance, and their insightful portrayal of the human condition. Artists like Correggio (Antonio Allegri da Correggio), active in nearby Parma, also explored a softness and grace that resonated with some of Moretto's sensibilities, though Correggio's style was generally more dynamic and sensuous.

In conclusion, Alessandro Bonvicino, "Il Moretto," was a pivotal figure in the Renaissance art of Lombardy. He navigated the rich artistic currents of his era, drawing from both local traditions and the powerful influence of Venice, to forge a personal style characterized by its solemn dignity, subtle emotionality, and distinctive, often silvery, tonalities. His altarpieces and portraits remain a testament to his skill and his enduring contribution to Italian art.