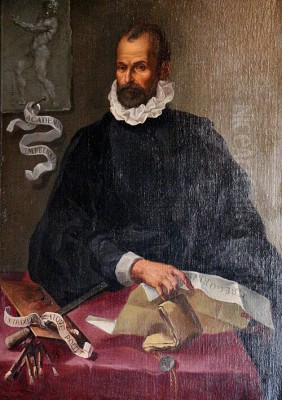

Girolamo Muziano, a name that resonates with the artistic vibrancy of the late Italian Renaissance, stands as a testament to a period of profound transition and innovation in art. Born in Acquafredda, near Brescia, in 1532, and passing away in Rome in 1592, Muziano's career bridged the High Renaissance's classical ideals with the emerging Mannerist tendencies and the devotional intensity of the Counter-Reformation. His journey from the Veneto's color-rich traditions to the monumental artistic landscape of Rome allowed him to forge a unique style, particularly distinguished in landscape painting and deeply expressive religious works. Muziano was not merely a painter; he was an innovator, an organizer, and a key figure in the institutionalization of art through his role in founding the Accademia di San Luca. His influence extended through his numerous commissions, his collaborations, and the dissemination of his style via prints, marking him as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, master of his time.

Early Life and Venetian Foundations

Girolamo Muziano's artistic genesis occurred in the fertile artistic environment of Northern Italy. His formative years were spent in Padua and, crucially, in Venice, the heart of a painterly tradition that prioritized color (colorito) and atmospheric effects over the Florentine emphasis on drawing (disegno). In this vibrant milieu, he is believed to have studied under the towering figure of Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), whose mastery of color, composition, and the expressive rendering of landscape and human emotion would leave an indelible mark on the young artist. Another significant mentor was Domenico Campagnola, himself a pupil of Titian and a notable painter and printmaker known for his idyllic landscapes that often featured in his religious and mythological scenes.

The Venetian school, with luminaries like Tintoretto (Jacopo Robusti) and Paolo Veronese also active during Muziano's formative period, was characterized by its dynamic compositions, rich palettes, and dramatic use of light. This environment undoubtedly shaped Muziano's early sensibilities, particularly his appreciation for the emotive power of landscape and the integration of natural settings into narrative compositions. His early works, though few survive or are definitively attributed, likely reflected this Venetian heritage, emphasizing painterly qualities and a keen observation of nature. This grounding in the Venetian tradition would prove foundational when he later moved to Rome, allowing him to introduce a distinct Northern Italian flavor to the Central Italian artistic scene. The skills honed in Venice, especially in depicting expansive, atmospheric landscapes, would become one of his most celebrated contributions.

Arrival in Rome and Early Acclaim

Around 1549, at the young age of approximately seventeen, Girolamo Muziano made the pivotal decision to relocate to Rome. The Eternal City was then the undisputed center of the art world, still basking in the monumental achievements of High Renaissance masters like Raphael (Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino) and Michelangelo Buonarroti, yet also pulsating with new artistic directions. For an ambitious young painter from the Veneto, Rome offered unparalleled opportunities for patronage, learning, and recognition. Muziano arrived with a style already imbued with Venetian colorism and a sensitivity to landscape, which set him apart from many of his Roman contemporaries.

His talent did not go unnoticed for long. One of the most significant endorsements of his early Roman period reportedly came from Michelangelo himself. The aging master, a dominant figure in Roman art, is said to have highly praised Muziano's painting, The Raising of Lazarus (created around 1555, now in the Pinacoteca Vaticana). According to accounts, Michelangelo declared that its author was one of the "greatest painters of the age." Such a commendation from an artist of Michelangelo's stature would have been invaluable, catapulting Muziano into the limelight and opening doors to prestigious commissions. This particular work, The Raising of Lazarus, showcases Muziano's ability to handle complex multi-figure compositions with dramatic intensity, while also integrating a carefully rendered landscape that adds to the scene's emotional depth, a hallmark that blended his Venetian training with Roman grandeur.

A Master of Landscape Painting

While Muziano was a versatile artist proficient in various genres, his most distinctive and perhaps most influential contribution lay in the realm of landscape painting. In 16th-century Italy, landscape was often relegated to a subsidiary role, serving merely as a backdrop for religious or historical narratives. Muziano, however, elevated its status, imbuing his natural settings with a profound sense of character and atmosphere that often became integral to the painting's overall meaning and emotional impact. This approach was deeply rooted in his Venetian training, particularly the influence of Titian and Campagnola, who were pioneers in depicting evocative, naturalistic landscapes.

In Rome, Muziano's landscapes stood out for their "powerful, precise, and beautiful" rendering of natural elements, as noted by contemporaries. He was particularly adept at depicting rugged, untamed scenery – rocky outcrops, dense forests, and winding streams – which he often populated with hermits, saints, or penitents. Works like St. Jerome Preaching to the Monks in the Desert exemplify this skill. Here, the vast, wild landscape is not just a setting but an active participant in the narrative, emphasizing the saint's asceticism and spiritual retreat. His trees were noted for their verisimilitude, and his ability to create a sense of depth and atmosphere was unparalleled among many of his Roman peers. This focus on landscape was innovative for Rome at the time and had a significant impact, influencing other artists, including Northern painters like Paul Bril and Matthijs Bril, who were also active in Rome and contributed to the development of landscape as an independent genre. Muziano's landscape drawings and prints further disseminated his style, solidifying his reputation as a "pittore di paesi" (painter of landscapes).

Religious Commissions and Counter-Reformation Art

The latter half of the 16th century in Rome was dominated by the spirit of the Counter-Reformation, a period of Catholic resurgence and reform following the Council of Trent (1545-1563). Art became a crucial tool for reaffirming Catholic doctrine, inspiring piety, and communicating religious narratives with clarity and emotional force. Girolamo Muziano, a devout Catholic, was well-suited to this artistic climate, and much of his career was dedicated to fulfilling religious commissions for churches, chapels, and religious orders. His works from this period often reflect the Counter-Reformation's emphasis on decorum, intelligibility, and devotional intensity.

One of his most significant altarpieces is The Circumcision of Christ (1587-1589), created for the high altar of the Chiesa del Gesù, the mother church of the Jesuit order in Rome. This painting is notable for its serene and sacred atmosphere, focusing on the solemnity of the ritual rather than any potentially gruesome details, aligning with Jesuit preferences for art that encouraged contemplation and inner feeling. Other important religious works include St. Paul the Hermit and St. Anthony, both painted for St. Peter's Basilica, showcasing his ability to depict figures with profound spiritual gravitas. He also created numerous frescoes and altarpieces for other Roman churches, such as Santa Maria degli Angeli e dei Martiri (e.g., The Handing Over of the Keys) and Santa Maria sopra Minerva (e.g., Prophets and Allegorical Figures, c. 1550). These works demonstrate his skill in large-scale narrative composition, his robust figure style often influenced by Michelangelo, and his characteristic integration of expressive landscapes. Artists like Scipione Pulzone, known for his intensely realistic and pious portraits, and Federico Barocci, with his soft, emotive religious scenes, were contemporaries also navigating the demands of Counter-Reformation art, each contributing to the diverse artistic responses of the era.

The Vatican Projects: Mosaics and Frescoes

Muziano's reputation and skill earned him prestigious commissions within the Vatican, the very heart of papal power and artistic patronage. He was involved in significant decorative projects, demonstrating his versatility beyond panel painting and fresco. One notable area of his expertise was mosaic design. He was highly regarded for his ability to translate the painterly qualities of his designs into the medium of mosaic, a testament to his understanding of form, color, and light. His work in this demanding medium earned him praise as a "perfect imitator of painting," indicating that his mosaic compositions retained the subtlety and dynamism of his painted works. This was crucial for large-scale, durable decorations in prominent Vatican spaces.

A major collaborative project was the decoration of the ceiling of the Gallery of Maps in the Vatican Palace, undertaken for Pope Gregory XIII. For this ambitious undertaking, Muziano worked alongside Cesare Nebbia, another prominent painter of the late 16th century. The Gallery of Maps itself is a stunning corridor frescoed with detailed maps of the Italian regions. The ceiling, adorned with scenes from the lives of saints and allegorical figures, was intended to complement the cartographic program below. Muziano and Nebbia's contributions to the ceiling frescoes would have required immense organizational skill, managing teams of assistants to execute the vast decorative scheme. This project highlights Muziano's standing as a leading artist capable of managing large-scale papal commissions, a role previously filled by giants like Raphael and Michelangelo. His involvement in such high-profile Vatican projects solidified his status within the Roman artistic hierarchy.

Collaborations and Workshop Practice

Like most successful artists of his era, Girolamo Muziano maintained an active workshop and engaged in numerous collaborations to fulfill the large volume of commissions he received. Collaboration was a practical necessity for large-scale projects, such as extensive fresco cycles or the decoration of entire chapels, and it also fostered an environment of artistic exchange. His most documented collaboration was with Cesare Nebbia, not only on the Vatican's Gallery of Maps but also on other projects, such as the decoration of the Florenzi Chapel in the church of Santa Maria in Aracoeli. A contract from 1579 for the Florenzi Chapel explicitly names Muziano as a financial guarantor and collaborator, indicating a close working relationship.

There is also scholarly suggestion of potential collaborations with Federico Zuccari, another leading figure in late Mannerist Roman painting. They may have worked together on decorative schemes at the Villa d'Este in Tivoli for Cardinal Ippolito II d'Este, and possibly on frescoes in the church of Santa Caterina della Rota. Federico, along with his brother Taddeo Zuccari, ran one of the most successful workshops in Rome, and interactions between such prominent artists were common. Muziano's workshop would have employed assistants and pupils who helped with preparatory work, transferring cartoons, and painting less critical areas of large compositions under his supervision. This system allowed for efficient production while ensuring the master's style and quality were maintained. Some sources also suggest possible, though less clearly defined, interactions or collaborations with artists like Matteo Neroni for works in Tivoli. The presence of followers, such as Gaspar Rem, further attests to the influence emanating from his workshop and artistic circle.

The Accademia di San Luca: A Legacy of Organization

Beyond his individual artistic achievements, Girolamo Muziano played a crucial role in the institutional development of the arts in Rome. He was a key figure in the establishment of the Accademia di San Luca (Academy of Saint Luke), an association of artists founded with the aim of elevating the status of artists, providing training, and fostering a sense of professional community. The Academy received its charter from Pope Gregory XIII in 1577, largely through the efforts of Muziano and other prominent artists. Muziano's involvement was so central that he is often credited as one of its principal founders and served as its first principe (head or president).

The founding of the Accademia di San Luca was a significant step in transforming the perception of artists from mere craftsmen to intellectuals and professionals. It provided a formal structure for artistic education, moving beyond the traditional workshop apprenticeship system, and offered a forum for discussing artistic theory and practice. Muziano's leadership in this endeavor underscores his organizational abilities and his commitment to the artistic community. The Academy, under various forms, has continued to exist to this day, a lasting testament to the vision of its founders. His role in the Accademia places him alongside other artist-organizers like Giorgio Vasari, who had earlier been instrumental in founding the Accademia delle Arti del Disegno in Florence. This initiative reflects a broader Renaissance trend of artists seeking greater autonomy and recognition for their profession.

Printmaking and the Dissemination of Style

Girolamo Muziano, like many of his contemporaries, recognized the power of printmaking as a means of disseminating his artistic inventions to a wider audience and enhancing his reputation beyond the immediate reach of his painted works. While he was not primarily an etcher or engraver himself, he frequently supplied designs for prints that were then executed by specialist printmakers. This practice allowed his compositions, particularly his innovative landscapes and expressive religious scenes, to circulate throughout Italy and even across the Alps, influencing artists in Northern Europe.

One of his most famous series of designs for prints was Six Penitents in the Wilderness. These images, depicting saints like Jerome, Mary Magdalene, and John the Baptist in rugged, evocative landscapes, were highly popular and became exemplars of Counter-Reformation piety. The dramatic natural settings, a hallmark of Muziano's style, were perfectly suited to conveying the themes of asceticism, contemplation, and spiritual struggle. These prints, often engraved by skilled craftsmen like Cornelis Cort, a Dutch engraver active in Italy who also reproduced works by Titian and other masters, helped to solidify Muziano's reputation as a master of landscape and a poignant interpreter of religious themes. The widespread availability of these prints ensured that Muziano's iconographic and stylistic innovations reached artists and patrons far removed from Rome, contributing to the broader European artistic discourse of the late 16th century.

Later Works and Mature Style

In his later career, Girolamo Muziano continued to be a prolific and sought-after artist, his style evolving while retaining its core characteristics. His mature works demonstrate a consolidation of his Venetian heritage with the monumental and often austere demands of Roman Counter-Reformation art. He maintained his commitment to expressive figure painting, often drawing inspiration from Michelangelo's powerful anatomy, but tempered by a Venetian sensitivity to color and atmosphere. His landscapes remained a strong feature, often imbued with a sense of melancholy or spiritual gravitas that resonated with the religious tenor of the times.

Commissions for major altarpieces and fresco cycles continued to occupy him. His work in the Cappella Gregoriana of St. Peter's Basilica, though involving mosaics, reflects the grandeur and devotional intensity expected in such a prominent location. Throughout his later years, he remained a respected figure in the Roman art world, his influence extending through his own works, his workshop, and his leadership role in the Accademia di San Luca. His ability to adapt to the evolving tastes and religious imperatives of papal Rome, while still infusing his art with a personal vision, particularly in his treatment of landscape, marks the strength of his mature style. He continued to work until shortly before his death in 1592, leaving behind a substantial body of work that significantly contributed to the artistic landscape of late 16th-century Rome. His later period saw the rise of younger artists like Giuseppe Cesari (Cavalier d'Arpino), who would further shape the transition towards the Baroque.

Anecdotes, Character, and Contextual Complexities

Girolamo Muziano's life, like that of many prominent figures of his time, was not confined solely to the studio. He was a man of deep religious conviction, a devout Catholic whose faith undoubtedly informed his artistic interpretations of sacred subjects. This piety aligned well with the Counter-Reformation ethos that permeated Rome during his career. Beyond his artistic and religious life, some accounts suggest a more multifaceted persona. There are mentions of him being involved in activities that extended into the socio-political sphere, though these are sometimes less clearly documented than his artistic endeavors.

For instance, there are historical references to Muziano undertaking diplomatic or advisory roles, possibly for influential patrons like the Medici family, which might have involved negotiations or missions, such as a reported, albeit unsuccessful, mission to Milan. Such activities, if accurately reported, would suggest a man of considerable worldly acumen and trustworthiness. More controversially, he is said to have faced an investigation by the Inquisition at one point, related to an accusation against the Bishop of Lucca. While the details are obscure, it hints at the complex and sometimes perilous intersections of art, religion, and power in 16th-century Italy. He was also reportedly involved as a mediator in an inheritance dispute concerning the Pico della Mirandola family, further indicating a respected position within society that went beyond his artistic talents. These fragments paint a picture of a man deeply embedded in the religious, social, and even political fabric of his time, navigating a world where artistic success was often intertwined with complex personal and public responsibilities.

Artistic Legacy and Historical Evaluation

Girolamo Muziano's position in art history has been subject to varied interpretations. For a long time, he was often categorized as a transitional figure, an artist of the "Maniera," caught between the High Renaissance and the full emergence of the Baroque, and perhaps overshadowed by more revolutionary figures. Some earlier art historical narratives tended to downplay the originality of artists from this period. However, more recent scholarship has increasingly recognized his specific and significant contributions, particularly his pioneering role in landscape painting within the Roman context and his sensitive articulation of Counter-Reformation piety.

His influence on landscape painting is undeniable. By infusing landscapes with emotional depth and making them integral to his compositions, he helped pave the way for the more independent landscape traditions that would flourish in the 17th century with artists like Claude Lorrain and Nicolas Poussin (though their styles were different, the groundwork for valuing landscape was laid). His religious works, with their blend of Michelangelesque strength and Venetian colorism, provided a model for devotional art that was both dignified and emotionally engaging. The dissemination of his compositions through prints ensured his influence extended geographically and temporally.

The founding of the Accademia di San Luca remains one of his most enduring legacies, highlighting his commitment to the professionalization and education of artists. While perhaps not as widely known today as some of his contemporaries like Titian or later Baroque masters like Caravaggio or Annibale Carracci, Muziano was a highly respected and successful artist in his own time. His works adorned major churches and papal palaces, and his skill was acknowledged by the most discerning patrons and fellow artists. Modern re-evaluation rightly positions him as a key innovator and a central figure in the rich artistic tapestry of late 16th-century Rome, an artist who skillfully navigated and contributed to a period of profound artistic and religious transformation.

Conclusion: A Multifaceted Renaissance Master

Girolamo Muziano emerges from the annals of art history not just as a painter of considerable skill, but as a multifaceted artist who left a significant imprint on the Roman art scene of the late 16th century. From his early training in the color-rich traditions of Venice under masters like Titian, he brought a unique sensibility to Rome, where he carved out a distinguished career. His mastery in rendering evocative and powerful landscapes set him apart, influencing the genre's development. As a painter of religious subjects, he responded adeptly to the spiritual currents of the Counter-Reformation, creating works of profound piety and emotional depth for the most important patrons, including the Papacy and the Jesuit Order.

His collaborations with artists like Cesare Nebbia on monumental projects such as the Vatican's Gallery of Maps, his influential role in founding and leading the Accademia di San Luca, and the dissemination of his style through printmaking all speak to a career of broad impact. While navigating the complex artistic, religious, and even political currents of his time, Muziano maintained a distinctive artistic voice. His ability to synthesize Venetian colorism with Roman monumentality, and to imbue both figures and landscapes with expressive power, secures his place as a pivotal figure in the transition from the High Renaissance to the early stirrings of the Baroque. Girolamo Muziano was, in essence, a complete artist of his time: a skilled practitioner, an influential teacher, an organizer, and a significant contributor to the enduring legacy of Italian art.