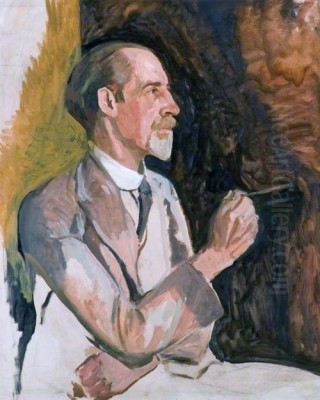

Algernon Mayow Talmage (1871–1939) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the landscape of British art, particularly within the Impressionist movement. An accomplished painter of landscapes, animals, and historical scenes, Talmage's career spanned a period of dynamic change in the art world. He was a respected teacher, an official war artist, and a man whose personal resilience in the face of physical adversity shaped his determined pursuit of art. His work, characterized by a sensitive handling of light and atmosphere, captured the essence of the English countryside, the rugged Cornish coast, and the poignant realities of war. Though his fame may have been eclipsed at times by contemporaries such as Sir Alfred Munnings, a closer examination reveals an artist of considerable skill, depth, and influence.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born on February 23, 1871, in Fifthill, Oxfordshire, Algernon Talmage's early life was marked by a significant event that would impact him physically but not deter his spirit. A childhood accident involving a firearm resulted in a permanent disability to his left hand. Despite this, Talmage developed into a remarkably adept individual, becoming an excellent horseman and a proficient shot – skills that perhaps later informed his keen eye for animal anatomy and movement, particularly evident in his equine subjects.

His formal artistic education began at a pivotal institution for many aspiring artists of his generation: Hubert von Herkomer's School of Art in Bushey, Hertfordshire. Herkomer, a Royal Academician of German birth, ran a highly successful and influential school that emphasized rigorous training and direct observation. The Bushey school was known for its somewhat unconventional approach compared to the more staid Royal Academy Schools, fostering a practical, hands-on method that appealed to many. It was here that Talmage would have honed his foundational skills in drawing and painting, likely being exposed to a variety of artistic theories and practices.

Following his time at Bushey, Talmage was drawn to the burgeoning art colony of St Ives in Cornwall. This picturesque fishing village, with its unique quality of light and rugged coastal scenery, had become a magnet for artists from the late 19th century onwards, paralleling the development of the nearby Newlyn School, which included notable figures like Stanhope Forbes and Walter Langley. The St Ives artistic community offered a supportive and stimulating environment, encouraging plein air (outdoor) painting and a focus on capturing the immediate sensory experience of the landscape.

The St Ives Influence and an Emerging Style

The move to St Ives was a formative period for Talmage. The Cornish light, renowned for its clarity and brilliance, profoundly influenced his palette and technique. He immersed himself in the local art scene, working alongside and learning from other artists who had gathered there. By 1900, his commitment to the area and his growing reputation enabled him to establish his own art school in St Ives. This school, known as the Talmage School of Painting or sometimes referred to as the St Ives School of Landscape and Marine Painting (though often informally linked with Julius Olsson's school), attracted numerous students eager to learn from his approach.

During this period, Talmage's style solidified. He embraced the tenets of Impressionism, focusing on the depiction of light and its effects on colour and form. His landscapes were not mere topographical records but evocative renderings of atmosphere and mood. He was particularly adept at capturing the transient effects of weather and the subtle shifts in light at different times of day, with a special fondness for the crepuscular light of dawn and dusk. His work often featured the harbours, cliffs, and rolling countryside of Cornwall, rendered with fluid brushwork and a palette that, while grounded in naturalism, was often heightened to convey emotional and sensory impact. Artists like Louis Grier and Adrian Stokes were also prominent in St Ives at this time, contributing to a vibrant artistic dialogue. The influence of earlier French Impressionists such as Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro was certainly in the air, filtered through a distinctly British sensibility.

An Impressionist's Vision: Light, Landscape, and Atmosphere

Talmage's dedication to Impressionist principles is evident in many of his works. He sought to capture the fleeting moment, the "impression" of a scene as perceived by the artist. This involved a meticulous study of light and its interplay with the natural world. His paintings often exhibit a luminous quality, with light seeming to emanate from within the canvas itself. He was a master of depicting skies, whether clear and bright, or overcast and moody, understanding their crucial role in setting the overall tone of a landscape.

Works such as Cornish Harbour and Cliffs, Isle of Wight exemplify his skill in this regard. In Cornish Harbour, one can almost feel the dampness in the air and see the soft, diffused light reflecting off the water and the wet stones of the quay. His depiction of the fishing boats and the harbour architecture is precise yet painterly, avoiding an overly photographic realism in favour of an atmospheric truth. Similarly, Cliffs, Isle of Wight would likely showcase his ability to render the dramatic forms of the coastline, perhaps under the raking light of a low sun, highlighting textures and creating strong contrasts between light and shadow.

His exploration of landscape was not confined to Cornwall or the British Isles. He also painted scenes in France and Holland, broadening his visual vocabulary and responding to different qualities of light and environment. Regardless of the location, his approach remained consistent: a deep engagement with the natural world and a desire to translate its visual poetry onto canvas. His contemporaries in British Impressionism, such as Philip Wilson Steer and Walter Sickert, were also exploring similar concerns, though often with different thematic focuses or stylistic nuances.

War Artist for Canada: Documenting a Different Landscape

The outbreak of the First World War brought a significant new dimension to Talmage's career. His established reputation and his particular skill in depicting horses made him a suitable candidate for an important commission. He was appointed as an official war artist for the Canadian government, under the auspices of the Canadian War Memorials Fund, which was spearheaded by Lord Beaverbrook. His specific brief was to document the activities of the Canadian Army Veterinary Corps (CAVC) on the Western Front.

This role took Talmage into the heart of the war effort, albeit focused on a less commonly depicted aspect: the care and treatment of the vast numbers of horses and mules that were essential to the logistics of the Allied armies. His paintings from this period are powerful and poignant. Works like A Mobile Veterinary Unit in France and Wounded Horses Leaving the Front provide a stark insight into the realities of war for these animals. A Mobile Veterinary Unit in France likely depicts the organized, almost clinical environment of a field veterinary station, with Canadian personnel tending to injured equines amidst the backdrop of a war-torn landscape.

Wounded Horses Leaving the Front is particularly evocative, capturing the suffering of the animals and the grim determination of the soldiers leading them away from the battlefield. These paintings often contrast the chaos and destruction of war with moments of quiet care and the enduring bond between humans and animals. Talmage did not shy away from the harshness of the subject matter, yet his treatment remained sensitive and humane. His war art serves as an important historical record and a testament to the often-overlooked role of animals in the conflict. Other artists, like Paul Nash and C.R.W. Nevinson, were creating iconic images of the trenches and battlefields, while Talmage provided a unique perspective on a vital support service.

The Founding of Australia: A Monumental and Contested Work

One of Algernon Talmage's most famous, and indeed most ambitious, works is The Founding of Australia by Captain Arthur Phillip R.N. Sydney Cove, Jan. 26th 1788. This large-scale historical painting was completed in 1937, commissioned to commemorate the 150th anniversary of the arrival of the First Fleet in Australia. The painting depicts the moment when Captain Arthur Phillip and his officers are shown raising the British flag at Sydney Cove, with ships of the First Fleet visible in the background and a gathering of convicts and marines.

The painting is a grand, heroic portrayal of the event, rendered in a traditional academic style, albeit with Talmage's characteristic attention to light and composition. It was intended as a celebratory image, marking a key moment in the colonial history of Australia. For many years, it was widely reproduced and became an iconic representation of Australia Day. The work was presented to the Tate Gallery in London by the Dominions Office and was later transferred to the Australian National Maritime Museum.

However, in more recent decades, The Founding of Australia has become a subject of considerable debate and controversy. From the perspective of Indigenous Australians, the arrival of the First Fleet marks the beginning of invasion, dispossession, and immense suffering. The painting's heroic and romanticized depiction of the event is seen by many as a symbol of colonial triumphalism, ignoring the devastating impact on the Aboriginal population. It has been contrasted with later, more critical artistic responses to Australia's colonial past by both Indigenous and non-Indigenous artists. This shift in interpretation highlights how the meaning and reception of artworks can change dramatically over time, reflecting evolving societal values and historical understanding. The painting, therefore, exists in a complex space: a significant artistic achievement of its time, and a potent symbol within ongoing discussions about history, identity, and reconciliation in Australia.

A Respected Teacher and Mentor

Beyond his own prolific output, Algernon Talmage made a significant contribution to art education. His school in St Ives was a testament to his commitment to fostering new talent. He was known as an encouraging and insightful teacher, emphasizing the importance of direct observation and plein air painting. He encouraged his students to find the "sunshine in the shadows," a piece of advice that particularly resonated with one of his most famous pupils, the Canadian artist Emily Carr.

Emily Carr studied with Talmage in St Ives around 1910. She had previously found the teaching of Julius Olsson, another prominent St Ives artist and teacher, less to her liking, preferring Talmage's approach. Talmage's guidance was instrumental in helping Carr to develop her own distinctive style, particularly in her depiction of the landscapes and Indigenous cultures of British Columbia. His emphasis on capturing light and atmosphere, and his encouragement to find a personal voice, left a lasting impression on her.

Hilda Fearon, another notable British artist associated with the Impressionist movement, also received instruction from Talmage in Cornwall. Fearon became known for her sensitive interior scenes and landscapes, and her time with Talmage would have undoubtedly contributed to her development. Helen McCann is another artist mentioned as having been an early student of Talmage. Through his teaching, Talmage helped to shape a new generation of painters, passing on the principles of Impressionism and the importance of individual artistic vision. His influence extended beyond technical instruction; he fostered a supportive environment where students could experiment and grow.

Relationships with Contemporaries

The art world of the early 20th century was a relatively close-knit community, and Talmage interacted with many of the leading figures of his day. His artistic stature was, for a time, considered comparable to that of Sir Alfred Munnings, one of the most successful and celebrated British painters of horses and rural life. Both artists shared a passion for equine subjects and traditional representational painting, though Munnings would achieve greater and more sustained public fame, particularly for his opposition to Modernism.

In St Ives, Talmage was part of an active artistic circle. He co-taught with Julius Olsson, despite their different teaching styles, and collaborated in fostering the artistic environment of the town. Olsson was particularly renowned for his seascapes and nocturnes. Other artists in their circle included Louis Grier and Adrian Stokes, the latter known for his temperate landscapes and genre scenes. The atmosphere in St Ives appears to have been largely collaborative rather than fiercely competitive, with artists sharing ideas and supporting each other's endeavors. The Newlyn School artists, such as Stanhope Forbes, Walter Langley, and Norman Garstin, though geographically distinct, were part of the same broader Cornish art phenomenon, all drawn by the region's unique character. Laura Knight, another prominent artist who spent time in Cornwall, also achieved great success with her vibrant depictions of everyday life and the ballet.

Talmage exhibited regularly at prestigious venues such as the Royal Academy in London, the Royal Society of British Artists, and the Royal Institute of Oil Painters, indicating his acceptance and recognition within the established art institutions of the time. He received several awards for his work, further cementing his reputation during his lifetime.

Later Career, Fading Recognition, and Rediscovery

Throughout his career, Algernon Talmage remained committed to his artistic vision. He continued to paint and exhibit, producing a substantial body of work. However, as artistic tastes began to shift in the post-war era, with the rise of Modernism and abstract art, the popularity of traditional representational painting, including British Impressionism, began to wane. Artists like Talmage, whose work was rooted in an earlier aesthetic, found themselves increasingly out of step with the avant-garde.

Consequently, after his death on September 14, 1939, in Romsey, Hampshire, Talmage's reputation gradually faded from public consciousness. He became one of many talented artists of his generation whose contributions were somewhat overshadowed by changing fashions and the passage of time. He has even been described as one of Britain's "buried Impressionists," a testament to how his significant achievements were, for a period, largely overlooked by mainstream art history.

In recent years, however, there has been a renewed interest in British Impressionism and a re-evaluation of artists like Algernon Talmage. Exhibitions and scholarly research have brought his work back into the spotlight, particularly in the UK and Australia. His paintings are held in numerous public collections, including the Tate Britain, the Imperial War Museum, the Canadian War Museum, and various regional galleries. This resurgence of interest allows for a more nuanced appreciation of his skill, his versatility, and his place within the broader narrative of British art.

Enduring Significance

Algernon Talmage's legacy is multifaceted. As a painter, he was a gifted exponent of British Impressionism, capturing the beauty and atmosphere of the landscapes he loved with sensitivity and skill. His equine paintings demonstrate a profound understanding of animal anatomy and movement, while his historical work, notably The Founding of Australia, remains a significant, if complex, cultural artifact.

As a war artist, he provided a unique and valuable record of the Canadian Army Veterinary Corps, highlighting an often-neglected aspect of the First World War. His contributions to art education, particularly his mentorship of Emily Carr, had a lasting impact on the development of other artists.

Though his fame may have fluctuated, the quality of Algernon Talmage's art endures. His ability to convey light, mood, and a deep connection to his subject matter ensures his continued relevance. He was an artist who, despite personal challenges and the shifting tides of artistic fashion, remained true to his vision, leaving behind a body of work that continues to resonate with viewers today. His story is a reminder of the rich and diverse tapestry of British art and the importance of re-examining and appreciating the contributions of artists who may have, for a time, slipped from prominent view. Algernon Mayow Talmage deserves recognition as a dedicated and talented artist whose work enriches our understanding of British art in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.