Helen Galloway McNicoll stands as a pivotal figure in Canadian art history, celebrated for her luminous contributions to Impressionism during a period of significant artistic and social change. Despite a tragically short career, her work left an indelible mark, characterized by its vibrant depiction of sunlight, intimate portrayals of women and children, and a distinctly modern sensibility. Her journey from a privileged upbringing in Montreal to the art colonies of Europe, all while navigating the challenges of profound deafness, speaks to a remarkable resilience and dedication to her craft. This exploration delves into her life, artistic development, key works, and her enduring legacy within the Canadian and international art scenes.

Early Life and Formative Influences

Born in Toronto on December 14, 1879, to David McNicoll, a prominent executive with the Canadian Pacific Railway, and Emily Pashley McNicoll, Helen enjoyed a comfortable upbringing. The family later moved to Montreal, a burgeoning cultural hub. Her early life was profoundly impacted at the age of two when a bout of scarlet fever left her completely deaf. This sensory deprivation, rather than hindering her, arguably sharpened her visual acuity and fostered a deep reliance on observation, a trait that would become central to her artistic practice.

Her family's social standing and financial means provided her with opportunities often unavailable to women of her time. Recognizing her artistic inclinations, they supported her pursuit of art. She began her formal art education at the Art Association of Montreal (AAM), studying under William Brymner. Brymner, a highly respected and influential teacher, had himself studied in Paris at the Académie Julian and was instrumental in introducing more modern, European-influenced approaches to Canadian art students. He encouraged a directness of observation and a sensitivity to light and atmosphere, principles that resonated deeply with McNicoll and laid the groundwork for her later Impressionistic style. Other students of Brymner who would also make significant marks on Canadian art included A.Y. Jackson, Clarence Gagnon, and Edwin Holgate, though McNicoll's path would diverge somewhat from the nationalistic landscape focus of the future Group of Seven.

Artistic Training and European Sojourns

Seeking to broaden her artistic horizons, McNicoll, like many aspiring North American artists of her generation, traveled to Europe. Around 1902, she enrolled at the prestigious Slade School of Fine Art in London. The Slade, under figures like Henry Tonks and Philip Wilson Steer, emphasized strong draughtsmanship but was also a place where Impressionistic ideas were being explored. Steer, in particular, was a leading British Impressionist, and his influence, alongside the general artistic ferment of London, would have been significant.

Her time in England was crucial. She further honed her skills at the St. Ives School in Cornwall, an artist colony that attracted painters drawn to its picturesque coastal scenery and unique quality of light. It was in St. Ives, around 1905, that she met the English painter Dorothea Sharp. This meeting marked the beginning of a close personal and professional relationship that would last for the rest of McNicoll's life. Sharp, who specialized in sunny depictions of children, shared McNicoll's artistic sensibilities. They often traveled and painted together, sharing studios and models, and their work from this period sometimes bears a close resemblance in theme and treatment. The supportive environment of artist colonies like St. Ives, and later in France, provided women artists like McNicoll and Sharp a degree of freedom and camaraderie that was essential for their development, away from the more rigid constraints of traditional academic settings. Other artists associated with the St. Ives school around this period included Julius Olsson and Algernon Talmage, who were known for their marine and landscape paintings.

McNicoll and Sharp also spent time in France, immersing themselves in the landscapes and artistic communities that had nurtured Impressionism. They frequented various artist colonies, absorbing the lingering influence of French Impressionists like Claude Monet, Berthe Morisot, and Camille Pissarro, whose emphasis on capturing fleeting moments and the effects of light en plein air (outdoors) was foundational to the movement.

The Impressionist Vision of Helen McNicoll

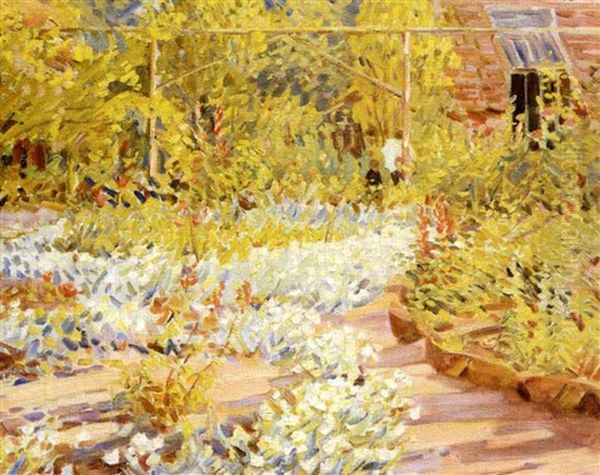

Helen McNicoll is best described as a Canadian Impressionist, though her style also incorporated elements that hinted at Post-Impressionism. Her paintings are characterized by their bright palettes, broken brushwork, and an almost palpable sense of sunlight and atmosphere. She excelled at capturing the transient effects of light, whether dappling through leaves, reflecting off water, or illuminating a sun-drenched field. Unlike some of her Canadian contemporaries who were beginning to forge a distinctly nationalistic landscape style focusing on the rugged Canadian wilderness, McNicoll’s subjects were often more intimate and domesticated, though almost always set outdoors.

Her deafness played an undeniable, if unquantifiable, role in her artistic vision. Unable to rely on auditory cues, her visual world became paramount. This heightened visual sensitivity is evident in the nuanced observation in her paintings – the subtle shifts in color, the careful rendering of light and shadow, and the quietude that pervades many of her scenes. Her compositions are often serene and uncluttered, focusing on the essential elements of the scene. There's a sense of peaceful immersion in her work, a quiet contemplation of the visual world.

She was particularly adept at conveying the warmth and brilliance of sunlight. Her canvases often glow with yellows, oranges, and warm greens, contrasted with cool blues and violets in the shadows, a hallmark of Impressionist technique. Her brushwork, while clearly Impressionistic in its application of distinct dabs of color, often retained a sense of form and structure, preventing her figures and landscapes from dissolving completely into light.

Key Themes and Subjects

McNicoll's oeuvre predominantly features women and children in tranquil, sunlit, rural settings. These are not typically portraits in the formal sense, but rather genre scenes where figures are integrated into their environment, often engaged in quiet activities like reading, sewing, tending to gardens, or simply enjoying a moment of leisure outdoors. Her depictions of women often subvert traditional Victorian representations. While her subjects are feminine and often engaged in traditionally female pastimes, they are also portrayed with a sense of quiet agency and self-possession, often absorbed in their own worlds.

Children are a recurring motif, depicted with a naturalism and tenderness that avoids sentimentality. They are often shown playing, exploring, or simply existing within the landscape, their bright clothing adding vibrant accents to her compositions. These scenes evoke a sense of innocence and the simple joys of rural life, a popular theme among Impressionist painters who sought an escape from the increasing industrialization of urban centers.

Her landscapes, while often serving as backdrops for her figures, are rendered with great sensitivity. She favored cultivated landscapes – gardens, orchards, meadows – rather than wild, untamed nature. This preference aligns with the Impressionist interest in the interplay between humanity and the natural world, particularly scenes of leisure and everyday life in suburban or rural settings. The theme of sunlight is, perhaps, the most pervasive in her work, acting almost as a subject in itself, transforming ordinary scenes into moments of radiant beauty.

Notable Works

Several paintings stand out as exemplary of McNicoll's style and thematic concerns:

The Apple Gatherer (c. 1911): This work showcases her skill in depicting figures in a sun-dappled landscape. A woman reaches for apples in an orchard, the light filtering through the leaves creating a mosaic of color on her dress and the ground. It’s a harmonious scene of gentle activity and natural abundance.

Sunny Days (date unknown): True to its title, this painting (and others with similar titles or themes) captures the essence of a bright, warm day. Often featuring children playing or women relaxing in a sunlit garden or field, these works are characterized by their vibrant color and joyful atmosphere.

In the Shadow of the Tree (c. 1914): This painting demonstrates McNicoll's mastery of light and shadow. Figures are shown resting or conversing under the cool shade of a large tree, while the background landscape is bathed in bright sunlight. The contrast creates a dynamic yet peaceful composition, highlighting her ability to handle complex lighting conditions.

The Chintz Sofa (c. 1913): While many of her works are set outdoors, this interior scene is notable. It depicts a woman, possibly Dorothea Sharp, reclining on a brightly patterned chintz sofa, light streaming in from a window. The interplay of patterns and the relaxed pose of the figure create an intimate and modern feel. It reflects the influence of artists like Edouard Vuillard or Pierre Bonnard, who were known for their intimate interior scenes.

The Open Door (c. 1913): This painting features a woman seated just inside an open doorway, sewing, with a sunlit garden visible beyond. The composition, with its framing device and the juxtaposition of interior and exterior spaces, is sophisticated. It can be interpreted as symbolic of women's expanding horizons, looking out from the domestic sphere towards new possibilities, a subtle nod to the changing roles of women in the early 20th century.

Under the Shadow of the Tent (c. 1914): This work, likely painted during one of her excursions with Dorothea Sharp, often features figures sheltered by a beach tent or awning, with the bright expanse of the seaside beyond. It captures the leisure activities becoming popular at the time and again showcases her skill with light.

These works, among others, demonstrate her consistent engagement with Impressionist principles while developing a personal style marked by its serenity and luminous color.

A Network of Artists: Collaborations and Contemporaries

Helen McNicoll’s career unfolded within a vibrant international art scene. Her most significant artistic relationship was undoubtedly with Dorothea Sharp (1874-1955). Their shared artistic interests, travels, and mutual support were crucial. Sharp, like McNicoll, favored bright, sunlit scenes of children and women, and their styles often converged. This close collaboration was not uncommon among women artists of the period, who often formed supportive networks to navigate a male-dominated art world.

In Canada, her primary mentor was William Brymner (1855-1925). While she was abroad for much of her productive career, her work was exhibited in Canada and recognized alongside that of other Canadian artists exploring modern tendencies. These included James Wilson Morrice (1865-1924), another Montrealer who spent much of his career in Europe and was a pioneer of modern art in Canada, known for his subtle, Whistlerian landscapes. Maurice Cullen (1866-1934) was another key figure in Canadian Impressionism, particularly noted for his snow scenes and depictions of Quebec City. Marc-Aurèle de Foy Suzor-Coté (1869-1937) also embraced Impressionist techniques, often depicting Quebec rural life and landscapes with vigorous brushwork. Clarence Gagnon (1881-1942), a contemporary of McNicoll, also studied with Brymner and later in Paris, becoming known for his vibrant depictions of Quebec landscapes.

Among female Canadian artists, Laura Muntz Lyall (1860-1930) was an important predecessor and contemporary who also gained international recognition for her Impressionistic paintings of women and children. Florence Carlyle (1864-1923) was another significant Canadian woman artist who studied abroad and achieved success with her figure paintings and portraits. Although McNicoll died before the formal establishment of the Beaver Hall Group in Montreal in 1920, her modern approach and focus on female subjects foreshadowed the concerns of many of its members, such as Prudence Heward (1896-1947), Lilias Torrance Newton (1896-1980), Anne Savage (1896-1971), and Sarah Robertson (1891-1948). These artists, many of whom also studied with Brymner, would continue to push the boundaries of modern art in Canada, with a strong representation of female perspectives.

In the broader European context, McNicoll’s work aligns with the ongoing legacy of Impressionism and the emergence of various Post-Impressionist styles. The St. Ives art colony, where she spent considerable time, was a hub for artists like Stanhope Forbes (1857-1947) and Elizabeth Forbes (1859-1912) of the Newlyn School (nearby St. Ives), who focused on realist and plein air depictions of local life, often with an Impressionistic handling of light. The broader influence of French Impressionists like Berthe Morisot (1841-1895), with her intimate portrayals of women and children, and American expatriates like Mary Cassatt (1844-1926), who shared similar thematic concerns, provides a wider context for McNicoll's artistic choices.

Recognition and Achievements

Despite her relatively short career, Helen McNicoll achieved considerable recognition. In 1908, she was awarded the prestigious Jessie Dow Prize from the Art Association of Montreal, a significant honor that acknowledged her talent early on. Her work was regularly accepted into major exhibitions in both Canada and Britain. She exhibited with the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts (RCA), to which she was elected an Associate in 1914, and the Ontario Society of Artists.

A particularly noteworthy achievement was her election to the Royal Society of British Artists (RBA) in 1913. This was a significant honor for any artist, and especially for a colonial woman, indicating the high regard in which her work was held in London, then a major center of the art world. Her paintings were praised by critics for their freshness, technical skill, and charming subject matter. She was seen as one of the leading exponents of Impressionism in Canada, successfully translating the European movement into a personal and appealing idiom.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Helen McNicoll's promising career was cut short by complications from diabetes. She died in Swanage, Dorset, England, on June 27, 1915, at the young age of 35. Her death was a significant loss to the Canadian art world. In the years immediately following her death, her reputation remained strong, with memorial exhibitions and continued critical acclaim. However, as artistic tastes shifted in Canada towards the nationalistic landscapes of the Group of Seven, the contributions of Impressionists like McNicoll, particularly those who spent much time abroad or focused on more "feminine" subjects, were somewhat overshadowed for a period.

In recent decades, however, there has been a significant reassessment of her work. Art historians and curators have rediscovered the quality and modernity of her paintings, recognizing her as a key figure in the development of Canadian Impressionism and an important woman artist of her generation. Her work is now seen not just for its aesthetic appeal but also for its subtle engagement with themes of modernity and the changing roles of women. Her depictions of women in moments of quiet independence and leisure, often in outdoor settings that suggest freedom and connection with nature, resonate with contemporary feminist art historical interpretations.

Her deafness, once perhaps seen as a limitation, is now often considered in the context of how it may have uniquely shaped her visual perception and artistic focus, leading to a heightened sensitivity to the nuances of light, color, and composition. Her ability to overcome this challenge and achieve international recognition is a testament to her talent and determination.

Today, Helen McNicoll's paintings are held in major public collections across Canada, including the National Gallery of Canada, the Art Gallery of Ontario, and the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. Her work continues to be celebrated in exhibitions and scholarly publications, securing her place as one of Canada's most accomplished and beloved Impressionist painters. She brought a distinctively bright and optimistic vision to Canadian art, capturing the fleeting beauty of sunlight and the quiet grace of everyday life with a skill and sensitivity that remains captivating.

Conclusion

Helen Galloway McNicoll's life and art offer a compelling narrative of talent, resilience, and quiet innovation. As a pioneering Canadian woman artist, she navigated the challenges of her era and her personal circumstances to create a body of work that is both aesthetically delightful and historically significant. Her luminous canvases, filled with sunlight and serene figures, not only represent a high point of Canadian Impressionism but also offer a gentle yet modern perspective on the world she observed with such keen visual intelligence. Her legacy endures, reminding us of the diverse voices and visions that have shaped the rich tapestry of Canadian art.