Alphonse Maria Mucha stands as a towering figure in the landscape of late 19th and early 20th-century art. A Czech-born painter, illustrator, and graphic artist, Mucha became virtually synonymous with the Art Nouveau movement, his distinctive style captivating Paris and influencing design across the globe. Yet, his artistic journey extended far beyond the decorative elegance that brought him initial fame, culminating in a profound exploration of his Slavic heritage. His life, spanning from the Austro-Hungarian Empire to the turbulent rise of Nazism, reflects both the zenith of Belle Époque aesthetics and the deep currents of national identity shaping modern Europe.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born on July 24, 1860, in the small town of Ivančice, Moravia, then part of the Austrian Empire (now the Czech Republic), Alphonse Mucha displayed artistic inclinations from a young age. Anecdotes suggest his mother recognized his talent early, even tying a pencil around his neck so he could draw while crawling. Though possessing a good singing voice, which allowed him secondary school entry in Brno, his true passion lay in the visual arts. His application to the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague in 1878 was initially rejected, with the advice to find a different profession.

Undeterred, Mucha pursued his artistic path. He found work painting theatrical scenery, first in Moravia and then, more significantly, in Vienna from 1879. This practical experience honed his skills in large-scale composition and dramatic effect. A pivotal moment came when a fire destroyed his primary employer's business in Vienna in 1881. Left without work, Mucha relocated to Mikulov in southern Moravia, undertaking portrait and decorative commissions.

His talent caught the eye of Count Karl Khuen-Belasi, who hired Mucha to decorate Hrušovany Emmahof Castle with murals. Impressed by his work, the Count became his patron, agreeing to finance Mucha's formal art training. This support enabled Mucha to study at the Munich Academy of Fine Arts starting in 1885, further developing his technical abilities.

The Parisian Breakthrough: Sarah Bernhardt and the Rise of the "Mucha Style"

In 1887, Mucha moved to Paris, the undisputed center of the Western art world. He continued his studies at the Académie Julian and the Académie Colarossi, immersing himself in the vibrant artistic milieu of the French capital. He supported himself by producing illustrations for magazines and advertisements, gradually building a reputation. However, his true breakthrough arrived unexpectedly at the end of 1894.

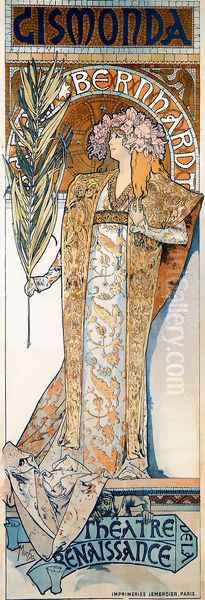

The legendary actress Sarah Bernhardt needed a new advertising poster for Victorien Sardou's play Gismonda, playing at the Théâtre de la Renaissance. With regular artists unavailable over the Christmas holidays, Mucha, working for the Lemercier printing house, took on the commission. Working under pressure, he created a revolutionary design: a tall, narrow poster featuring Bernhardt in an elegant, Byzantine-inspired costume, rendered with flowing lines, subtle pastel colors, and intricate ornamentation, crowned with an arch-like halo effect.

The Gismonda poster was an overnight sensation when it appeared on the streets of Paris in early January 1895. Its departure from the bolder, more colorful posters typical of artists like Jules Chéret or Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec was striking. Bernhardt was thrilled, and the public was captivated. This single work catapulted Mucha to fame and defined the visual language that would become known as the "Mucha Style."

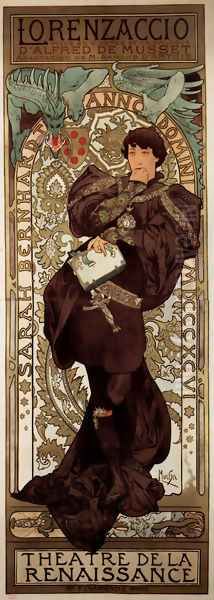

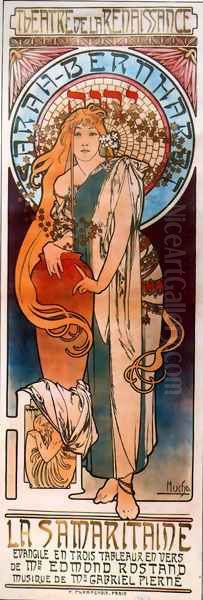

Bernhardt immediately offered Mucha a six-year exclusive contract to design not only her posters but also theatrical sets and costumes. This collaboration proved immensely fruitful, producing iconic posters for productions like La Dame aux Camélias, Lorenzaccio, La Samaritaine, and Médée. These works solidified Mucha's status as a leading figure of Art Nouveau, showcasing his mastery of line, decorative motifs, and idealized female forms. Some publishers, like Lemercier initially, found his style unconventional, but its public appeal was undeniable.

The Zenith of Art Nouveau: Decorative Panels, Advertising, and Design

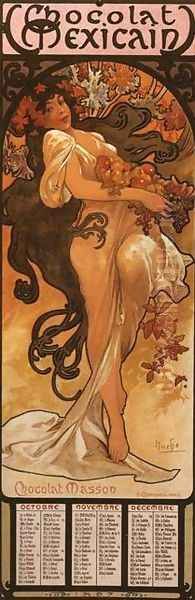

Riding the wave of his success with Bernhardt, Mucha became one of the most sought-after artists in Paris. His style, characterized by its sinuous lines, harmonious compositions, delicate color palettes, and integration of natural forms (flowers, leaves, tendrils) with elegant, often melancholic or contemplative female figures, perfectly captured the spirit of Art Nouveau. This "Mucha Style" was applied across a wide range of media.

He produced numerous series of decorative panels, or panneaux décoratifs, designed to be affordable art for the home. These lithographs, often depicting allegorical themes or personifications, became immensely popular. Famous series include The Seasons (1896, 1900), The Arts (1898 - depicting Poetry, Dance, Painting, Music), The Flowers (1898), The Times of the Day (1899), and The Precious Stones (1900). Each panel featured a beautiful woman gracefully embodying the theme, surrounded by elaborate borders and symbolic elements drawn from nature.

Mucha's distinctive aesthetic was also highly effective in advertising. He created memorable posters and packaging designs for brands like JOB cigarette papers, Moët & Chandon champagne, Nestlé, and various perfumes and biscuits. His ability to imbue commercial products with an aura of luxury, elegance, and allure made him a pioneer in modern graphic design and branding. His work demonstrated that commercial art could possess high artistic merit.

Beyond prints and posters, Mucha's creativity extended into three-dimensional design. He designed jewelry, often in collaboration with the jeweler Georges Fouquet, creating stunning pieces that echoed the motifs and forms found in his graphic work. He also worked on designs for textiles, carpets, wallpaper, and even architectural elements, contributing significantly to the concept of a unified Art Nouveau interior. His influence was pervasive, shaping the look of the Belle Époque. He even published design portfolios, such as Documents Décoratifs (1902), to disseminate his style and provide models for other artists and craftspeople.

Contemporaries, Context, and Influences

Mucha did not work in a vacuum. He was part of a broader European movement seeking new forms of expression at the turn of the century. In Paris, poster art was flourishing, with contemporaries like Jules Chéret, often called the "father of the modern poster," known for his vibrant colors and dynamic figures, and Théophile Steinlen, famous for his depictions of Montmartre life, particularly cats, and the iconic Le Chat Noir cabaret posters. Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, of course, brought a unique psychological depth and expressive line to his portrayals of Parisian nightlife. While Mucha shared the medium of the poster with these artists, his style, with its emphasis on decorative harmony and idealized beauty, set him apart.

Across Europe, Art Nouveau manifested in various ways. In Vienna, Gustav Klimt led the Secession movement, sharing with Mucha a love for ornamentation, symbolism, and the female form, albeit often with a more overt eroticism and psychological intensity. In Brussels, architects like Victor Horta were creating buildings with flowing, organic lines. In Glasgow, Charles Rennie Mackintosh developed a more geometric variant of the style. In Barcelona, Antoni Gaudí's architecture pushed organic forms to fantastical extremes. Decorative artists like René Lalique in France (glass and jewelry) and Louis Comfort Tiffany in the United States (glass) were also key figures whose work resonated with the Art Nouveau ethos.

Mucha's style drew from diverse sources. The influence of Japanese woodblock prints (Ukiyo-e), particularly the work of artists like Kitagawa Utamaro and Katsushika Hokusai, is evident in his flattened perspectives, strong outlines, and decorative compositions – a common inspiration for many Impressionist and Post-Impressionist artists as well. Echoes of Byzantine art, with its mosaics, halos, and rich patterns, can be seen in the hierarchical compositions and ornate details of his posters. The flowing lines and nature motifs also connect to the British Arts and Crafts movement and potentially the ethereal female figures of Pre-Raphaelite painters like Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Edward Burne-Jones. Furthermore, the folk art traditions of his native Moravia likely informed his use of pattern and color.

He also maintained connections with other artists. For a time, he shared a studio with Paul Gauguin. He had a brief teaching collaboration with James Abbott McNeill Whistler at the Académie Carmen around 1900, though it ended, they reportedly remained on friendly terms. Mucha's unique synthesis of these influences, combined with his personal vision, resulted in a style that was both deeply rooted in artistic traditions and strikingly modern.

Return to Bohemia: The Slav Epic

Despite his immense success and fame in Paris and internationally (he traveled to the United States several times between 1904 and 1910, securing commissions and teaching), Mucha felt a growing desire to dedicate his art to his homeland and his Slavic people. He believed his true calling lay beyond the commercial work that had made him famous. He dreamed of creating a monumental work celebrating the history and spirit of the Slavs.

This ambition began to take shape during his trips to the US, where he met Charles Richard Crane, a wealthy Chicago industrialist and Slavophile. Crane agreed to finance Mucha's grand project: Slovanská epopej (The Slav Epic). Returning to Bohemia (which would soon become part of the newly formed Czechoslovakia) in 1910, Mucha devoted much of the next two decades to this enormous undertaking.

The Slav Epic consists of twenty massive canvases (some measuring over 6 by 8 meters, or 20 by 26 feet) depicting key moments, myths, and spiritual milestones in the history of the Czechs and other Slavic peoples. The series covers events from ancient pagan times, the arrival of Saints Cyril and Methodius, the Hussite wars, up to the abolition of serfdom and scenes representing the dawning of a new era of Slavic unity and freedom in the modern age.

Stylistically, The Slav Epic marked a departure from the decorative elegance of Mucha's Parisian work. While retaining his skill in composition and color, the paintings adopted a more monumental, symbolic, and often realistic approach suited to their historical and allegorical themes. They convey a deep sense of history, spirituality, and national pride. Mucha meticulously researched the historical periods, costumes, and settings for each painting.

He completed the cycle in 1928 and gifted it to the city of Prague and the Czech people, fulfilling his long-held patriotic dream. The initial reception was mixed; by the late 1920s, Art Nouveau was out of fashion, and the epic's overt nationalism and allegorical style seemed somewhat anachronistic to the avant-garde movements of the time. However, it remains a unique and powerful testament to Mucha's dedication to his heritage.

National Identity and Later Works

Beyond The Slav Epic, Mucha actively contributed to the visual identity of the newly independent Czechoslovak Republic, formed in 1918 after the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. He poured his artistic talents into serving his nation, designing the country's first postage stamps and banknotes. These designs often incorporated the familiar motifs of his style – idealized figures, natural elements, and intricate patterns – adapted to express national symbols and aspirations.

He also designed other official documents, emblems for civic organizations, and even police uniforms. His work for the new state cemented his status as a national artist, deeply invested in the cultural life of his homeland. This patriotic fervor was a consistent thread throughout his later life.

Mucha was also deeply interested in spirituality and philosophy. He was a Freemason and involved in Czech Masonic lodges, seeing Masonry as aligned with his humanist and patriotic ideals. This spiritual dimension is often subtly present in his work, particularly in the symbolism employed in The Slav Epic and other allegorical pieces. His belief in universal harmony and human progress informed both his art and his worldview.

Final Years and Legacy

The rise of fascism in the 1930s cast a dark shadow over Europe and over Mucha's final years. As a prominent Czech patriot, a Freemason, and the creator of the nationalistic Slav Epic, he was considered suspect by the Nazi regime. When Germany invaded and occupied Czechoslovakia in March 1939, Mucha was among the first public figures arrested by the Gestapo.

Though already elderly (nearly 79) and frail, he was subjected to interrogation. The exact nature of the questioning is unclear, but it likely focused on his Masonic activities and his strong Slavic nationalism. He was eventually released, but the ordeal severely weakened his health. He contracted pneumonia shortly thereafter and died in Prague on July 14, 1939. His death, occurring under the shadow of Nazi occupation, was seen by many as a direct consequence of the persecution he suffered.

Despite the changing artistic fashions that saw Art Nouveau fall out of favor during the mid-20th century, Mucha's work experienced a significant revival starting in the 1960s. His posters and decorative panels regained immense popularity, recognized for their unique beauty and masterful design. The "Mucha Style" proved to have an enduring appeal.

His influence extends far beyond his own time. His pioneering work in graphic design and advertising laid groundwork for modern visual communication. His elegant lines, decorative sensibility, and idealized figures have notably influenced generations of illustrators, graphic artists, and even comic book and manga artists, particularly in the fantasy and shojo genres. The Mucha Museum in Prague, dedicated to his life and work, attracts visitors from around the world.

Alphonse Mucha remains celebrated for several key achievements: he was a defining master of the Art Nouveau style, creating some of its most iconic images; he successfully bridged the gap between fine art and commercial design, elevating the status of graphic arts; and he dedicated a significant part of his life to expressing his deep love for his Czech homeland and the broader Slavic culture through his monumental Slav Epic and designs for the Czechoslovak state. His legacy is that of a versatile and profoundly influential artist whose work continues to enchant and inspire.

Conclusion

Alphonse Mucha's artistic journey was one of remarkable transformation and enduring impact. From the decorative allure that captivated Belle Époque Paris to the profound historical narrative of The Slav Epic, his work consistently displayed a mastery of line, composition, and symbolic expression. As a central figure of Art Nouveau, he defined an era's aesthetic, leaving behind a legacy of elegance and beauty that transcended commercial application. As a Czech patriot, he dedicated his mature years to celebrating his heritage, contributing significantly to his nation's cultural identity. More than just a "master of Art Nouveau," Mucha was a complex, dedicated, and visionary artist whose influence continues to resonate in the worlds of art, design, and popular culture today.