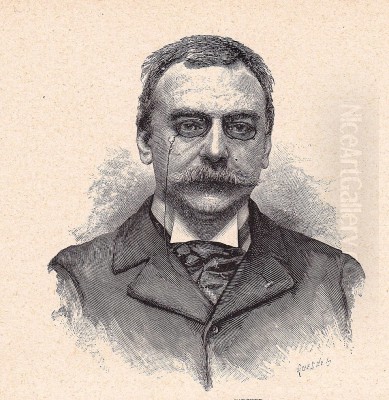

Eugène Samuel Grasset (1845-1917) stands as a monumental, albeit sometimes underappreciated, figure in the history of art, particularly as a pioneering force in the Art Nouveau movement. A Swiss-born artist who found his true calling in Paris, Grasset was a polymath of design, excelling as a painter, sculptor, illustrator, poster artist, typographer, and designer of furniture, stained glass, textiles, and jewelry. His prolific output and influential teaching career left an indelible mark on the decorative arts at the turn of the 20th century, shaping a visual language that sought to integrate art into every facet of daily life.

Early Life and Formative Influences

Born in Lausanne, Switzerland, on May 25, 1845 (some sources cite 1841, though 1845 is more commonly accepted), Eugène Grasset was immersed in an artisanal environment from a young age. His father, a cabinetmaker and sculptor, provided an early exposure to craftsmanship and design principles. This familial background undoubtedly nurtured his innate artistic talents. He initially pursued formal studies in architecture at the Zurich Polytechnic School under Gottfried Semper's disciple, a period that instilled in him a strong sense of structure and composition.

A pivotal experience in his youth was a trip to Egypt in 1866. The art and architecture of ancient Egypt, with its stylized forms, hieroglyphic narratives, and decorative richness, left a lasting impression on the young Grasset. This journey broadened his visual vocabulary and likely contributed to his later interest in non-Western artistic traditions and symbolic representation. Before settling in Paris, he also worked as a painter and sculptor in Lausanne, honing his skills across various media. His early art education included tutelage under François Bocion, a notable Swiss painter.

Arrival in Paris and the Blossoming of a Career

In 1871, at the age of 26, Grasset made the decisive move to Paris, the undisputed art capital of the world. This relocation marked the true beginning of his multifaceted career. Initially, he found work designing decorative patterns for fabric manufacturers, as well as creating designs for furniture, ceramics, and jewelry. His talent did not go unnoticed, and he soon began collaborating with prominent figures and firms.

One significant early collaborator was Charles Gillot, a pioneering printer who specialized in a new photomechanical relief printing process called gillotage. This partnership was crucial for Grasset, allowing his intricate designs to be reproduced with fidelity. Through Gillot, Grasset became involved in a wide array of projects, including book illustrations and poster design, which would become one of his most celebrated métiers. His meticulous attention to detail and his ability to synthesize diverse influences quickly set him apart.

The Distinctive Style of Eugène Grasset

Grasset's artistic style is a rich tapestry woven from various threads. A profound and transformative influence was Japonisme – the European fascination with Japanese art, particularly ukiyo-e woodblock prints by masters like Katsushika Hokusai and Utagawa Hiroshige. Grasset absorbed their flattened perspectives, strong outlines, asymmetrical compositions, and decorative use of natural motifs, especially flora and fauna. These elements became hallmarks of his work.

Another significant source of inspiration was medieval art, particularly Gothic manuscripts, stained glass, and architectural ornamentation. He admired the craftsmanship, the symbolic depth, and the integration of text and image found in medieval works. This interest aligned with the Gothic Revival championed by figures like Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, whose theories on rational structuralism in Gothic architecture also resonated with Grasset's architectural background.

Grasset masterfully blended these historical and exotic influences with a keen observation of nature. His designs frequently feature elegant, stylized depictions of plants, flowers, birds, and female figures. These figures, often melancholic or contemplative, are typically rendered with flowing lines and adorned in elaborate, almost Pre-Raphaelite drapery, reminiscent of artists like Dante Gabriel Rossetti or Edward Burne-Jones, though Grasset's interpretation was distinctly his own. His compositions are characterized by a strong sense of order, clarity, and decorative harmony, often framed by intricate borders.

A Pioneer in Poster Art

The late 19th century witnessed the golden age of the poster in Paris, and Grasset was at the forefront of this artistic revolution. While Jules Chéret is often hailed as the "father of the modern poster" for his vibrant, painterly lithographs, Grasset brought a different sensibility to the medium. His posters are more graphic, with clearly defined lines, carefully balanced compositions, and often a more subdued, symbolic color palette.

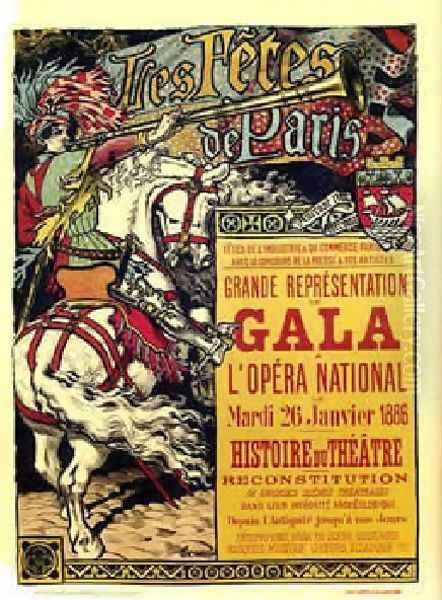

One of his most iconic early posters was for "Les Fêtes de Paris" (1886). However, it was his work for American publications that significantly boosted his international reputation. His 1892 Christmas cover for Harper's Magazine was a sensation, leading to further commissions. His poster "The Sun of Austerlitz" (Le Soleil d'Austerlitz) for The Century Magazine's serialized life of Napoleon (1894) is a masterpiece of historical evocation and graphic design, showcasing his ability to integrate text and image seamlessly. Another notable poster, "Jeanne d'Arc Sarah Bernhardt" (circa 1890), for the famed actress, demonstrates his skill in portraiture and dramatic composition.

Grasset's posters often featured statuesque female figures, embodying allegorical themes or representing the product advertised. These "Grasset girls," with their distinctive profiles and elaborate attire, became a recognizable trope within Art Nouveau. His approach influenced a generation of poster artists, including Paul Berthon, one of his most notable students, as well as contemporaries like Alphonse Mucha, whose style, while more overtly sensual and decorative, shared common roots with Grasset's work. Other prominent poster artists of the era, such as Théophile Steinlen and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, each contributed their unique visions to this burgeoning art form, but Grasset's contribution was foundational in its graphic precision.

Mastery in Illustration and Typography

Grasset's talents extended profoundly into the realm of book illustration and typography. His meticulous draftsmanship and understanding of printing processes made him an ideal illustrator. One of his most significant achievements in this field was the illustration of "Histoire des Quatre Fils Aymon, très nobles et très vaillans chevaliers" (Story of the Four Sons of Aymon, Very Noble and Very Valiant Knights), published in 1883. This lavishly illustrated medieval romance, printed by Charles Gillot, showcased Grasset's ability to evoke a historical atmosphere through detailed renderings of costumes, architecture, and heraldry, all within a distinctly Art Nouveau framework. The work was a triumph of chromolithography.

His interest in the harmonious relationship between text and image led him to typography. In 1898, he designed the "Grasset" typeface for the Fonderie G. Peignot et Fils. This elegant, legible typeface, with its slightly medieval flavor, became immensely popular and is still recognized today as a classic Art Nouveau font. It was famously used for the iconic "La Semeuse" (The Sower) logo of the Larousse dictionary, a design also attributed to Grasset or his circle. His commitment to the book as a total work of art, where every element from cover to typeface was considered, was characteristic of the Arts and Crafts ideals promoted by William Morris in Britain, though Grasset's aesthetic was uniquely French.

Ventures into the Broader Decorative Arts

True to the Art Nouveau ethos of breaking down the hierarchy between fine and applied arts, Grasset applied his design principles to a vast range of objects. He designed furniture that was both functional and aesthetically pleasing, often incorporating carved natural motifs and elegant lines. His work in stained glass was particularly noteworthy. He collaborated with the master glassmaker Félix Gaudin on numerous projects, creating luminous windows for both secular and religious buildings. Notable examples include "Spring" and "Autumn Afternoon," exhibited in 1894. His designs for stained glass often featured his characteristic female figures and intricate floral patterns, translating his graphic style into the translucent medium with great effect.

Grasset also designed ceramics, working with manufacturers like Auguste Delaherche. His designs for pottery often featured stylized plant forms and subtle glazes. Jewelry was another field where he excelled, creating pieces that were often symbolic and incorporated enamelwork and semi-precious stones, moving away from the ostentation of traditional gem-set jewelry towards a more artistic expression. He also produced designs for textiles, wallpaper, mosaics, and even postage stamps, demonstrating his versatility and his commitment to infusing everyday objects with artistic quality. This wide-ranging activity placed him in the company of other Art Nouveau polymaths like Henry van de Velde in Belgium or Charles Rennie Mackintosh in Scotland, all of whom sought to create unified artistic environments.

Educational Philosophy and Impact as a Teacher

Beyond his prolific output as a designer, Eugène Grasset was a highly influential educator. He taught decorative composition at the École Guérin from 1890 to 1903, and later at the École d'Art Graphique (which became part of the École Estienne) from 1903 to 1913, and also at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière. His teaching was based on rational principles of design derived from the study of nature and geometry.

Grasset published two seminal theoretical works that codified his teaching methods: "La Plante et ses applications ornementales" (Plants and Their Ornamental Applications, 1896), co-authored with Maurice Pillard Verneuil, and "Méthode de composition ornementale" (Method of Ornamental Composition, 1905). In these books, he advocated for a systematic approach to design, encouraging students to analyze natural forms and abstract them into decorative patterns. He emphasized the importance of underlying geometric structures and the harmonious arrangement of elements.

His students included a number of artists who went on to make significant contributions to Art Nouveau and Art Deco, such as Paul Berthon, Maurice Pillard Verneuil, Georges de Feure (though more a contemporary influenced by him), Augusto Giacometti (cousin of Alberto), and even, for a time, the Swiss architect Le Corbusier (then Charles-Édouard Jeanneret) is said to have been indirectly influenced by Grasset's pervasive design theories during his early studies. Grasset's pedagogical legacy was thus crucial in disseminating Art Nouveau principles and training a new generation of designers.

Collaborations and Artistic Milieu

Grasset's career was interwoven with the vibrant artistic milieu of fin-de-siècle Paris. His collaboration with Charles Gillot was foundational, providing him with the technical means to realize his graphic vision. His work with Félix Gaudin in stained glass was another key partnership. He was a contemporary of other leading Art Nouveau figures. While his style differed from the more flamboyant work of Hector Guimard in architecture or the ethereal glass of Émile Gallé and the Daum brothers in Nancy, they all shared the common goal of creating a modern, nature-inspired decorative language.

He exhibited regularly at the Salons, including the Salon des Cent, which was a key venue for poster artists and illustrators. His work was promoted by Siegfried Bing, whose gallery "L'Art Nouveau" gave the movement its name. While Grasset was perhaps less of a self-promoter than some of his contemporaries, his consistent quality and prolific output ensured his prominence. He was respected for his intellectual approach to design and his deep knowledge of historical and natural forms. His influence can also be seen in the work of American artists like Will H. Bradley, who adapted Art Nouveau aesthetics for an American audience.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

In his later years, Grasset continued to work and teach, though the tide of artistic fashion began to turn away from Art Nouveau towards the emerging modernisms of the early 20th century, such as Cubism, championed by artists like Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, and Fauvism, led by Henri Matisse. However, Grasset's emphasis on rational design principles and geometric underpinnings can be seen as a bridge towards the more geometric styles of Art Deco that would follow.

Eugène Grasset passed away in Sceaux, near Paris, on October 23, 1917. He left behind a vast body of work that continues to be admired for its elegance, craftsmanship, and intellectual rigor. His contributions were manifold: he was a pioneer of modern poster design, a master illustrator, an innovative typographer, a versatile decorative artist, and an influential teacher. His work is held in major museum collections worldwide, including the Musée d'Orsay and the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris, and The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Grasset's legacy lies in his successful fusion of artistic sensibility with practical application. He demonstrated that everyday objects could be imbued with beauty and meaning, and that art had a vital role to play in modern life. He helped to define the visual language of Art Nouveau, a movement that, despite its relatively short lifespan, had a profound impact on the development of 20th-century design. His insistence on a methodical approach to design, rooted in the study of nature and geometry, provided a valuable counterpoint to more intuitive or purely decorative tendencies, ensuring his enduring relevance in the history of art and design. His influence, though sometimes subtle, can be traced through the work of his students and in the broader evolution of graphic and decorative arts.