Amadeo Preziosi stands as a significant figure in 19th-century Orientalist art. Born into Maltese aristocracy, he defied familial expectations to pursue his artistic passion, ultimately dedicating his life and career to capturing the vibrant, multifaceted world of the Ottoman Empire, particularly its capital, Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul). His detailed watercolors and widely circulated lithographs offered European audiences an intimate glimpse into a culture often shrouded in mystery and stereotype, leaving behind a rich visual legacy that continues to fascinate and inform.

Noble Roots and Artistic Awakening

Amadeo Preziosi, or more formally, Aloysius-Rosarius-Amadeus-Raymundus-Andreas Preziosi, entered the world on December 2, 1816, in Valletta, Malta. He was born into a prominent noble family with deep roots in Maltese society. His father, Giovanni Francesco Preziosi, held significant local administrative positions, embodying the family's established status. His mother, Marguerita Preziosi (née Reynaud), was of French origin, adding a different cultural thread to his upbringing. The Preziosi family enjoyed respect and privilege on the island, which was then under British rule but retained strong Mediterranean and European connections.

Despite the comfortable path laid out for him, young Amadeo felt the pull of art over the legal career his father envisioned. The world of jurisprudence held little appeal compared to the expressive possibilities of line and color. This divergence in ambition created early tension, but Preziosi's artistic inclination proved too strong to ignore. His passion was not merely a fleeting interest but a profound calling that would shape the course of his entire life.

Recognizing his son's determination, though perhaps reluctantly, his father eventually permitted him to pursue formal art training. This decision led Preziosi to Paris, the undisputed center of the European art world in the 19th century. There, he enrolled at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts, immersing himself in rigorous academic training. He studied under established masters, honing his technical skills in drawing and painting, absorbing the prevailing Neoclassical and burgeoning Romantic influences that permeated the Parisian art scene. Artists like Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres were upholding the Neoclassical tradition, while Eugène Delacroix was championing the dramatic fervor of Romanticism, often with Orientalist themes himself. Preziosi's time in Paris was crucial, equipping him with the technical foundation and artistic sensibilities that would define his later work.

The Lure of the East: Constantinople Beckons

Returning to Malta after his studies, Preziosi found the local art scene perhaps too limited for his ambitions. The island, though historically rich, did not offer the same exotic allure and diverse subject matter that was increasingly captivating European artists. The "Orient"—a term broadly encompassing North Africa, the Ottoman Empire, and the wider Middle East—held a powerful fascination, fueled by travel literature, military campaigns, and a Romantic desire for the picturesque and the unknown.

In 1842, seeking new horizons and inspired by the growing trend of Orientalism, Preziosi made a life-altering decision: he moved to Constantinople. This was not a brief artistic excursion but the beginning of a decades-long residency. The Ottoman capital, straddling Europe and Asia, was a bustling, cosmopolitan metropolis, a melting pot of cultures, religions, and traditions. Its stunning architecture, crowded bazaars, scenic waterways, and diverse inhabitants offered an inexhaustible source of inspiration for an artist with Preziosi's keen eye for detail and character.

He settled in Pera (modern Beyoğlu), the district traditionally favored by Europeans and diplomats, establishing a studio that quickly gained renown. Unlike many European artists who made relatively short trips to the East, Preziosi immersed himself in the city's daily life. He learned local languages, navigated the complex social fabric, and developed a deep familiarity with the environment he depicted. This long-term commitment allowed him to move beyond superficial impressions and capture the nuances of Ottoman society with remarkable authenticity.

Chronicler of Ottoman Life

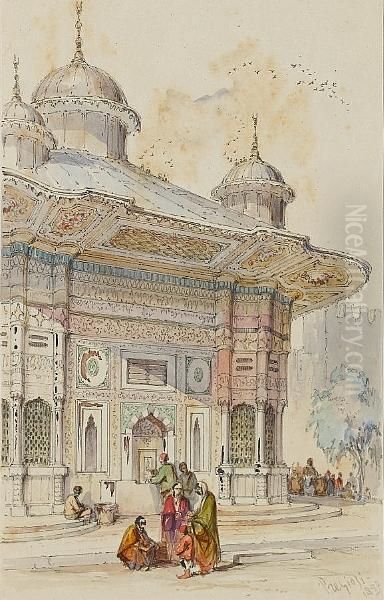

Preziosi's reputation grew steadily in Constantinople. He became known for his exceptional skill, particularly in watercolor, a medium perfectly suited to capturing the city's light and atmosphere, as well as the intricate details of architecture and costume. His subjects were drawn directly from the world around him: the bustling chaos of the Grand Bazaar, the serene courtyards of mosques, the lively traffic on the Golden Horn and the Bosphorus, the quiet moments in coffee houses, and the diverse array of people who populated the city—Turkish officials, Greek merchants, Armenian craftsmen, dervishes, water carriers, and elegantly dressed women.

His approach was characterized by meticulous observation and a dedication to accuracy. He rendered architectural details with precision and depicted traditional clothing with ethnographic care. Yet, his work was not merely documentary. Influenced by his Parisian training and the prevailing Romantic sensibility, he imbued his scenes with atmosphere and often a touch of idealized beauty. His compositions were carefully constructed, and his use of color was both vibrant and subtle, effectively conveying the textures of fabrics, the play of light on water, or the weathered surfaces of ancient stones.

Preziosi's studio in Pera became a popular stop for European travelers, diplomats, and officials visiting Constantinople. These visitors were eager to acquire visual souvenirs of their experiences in the exotic East, and Preziosi's detailed and evocative watercolors perfectly met this demand. His works served as more than just personal mementos; they helped shape the European visual understanding of the Ottoman Empire during a period of intense interest and political engagement.

Masterpieces in Watercolor and Print

While Preziosi produced numerous individual watercolors, some of his most influential work came in the form of published albums of chromolithographs. These albums allowed his images to reach a much wider audience in Europe. Two collections stand out:

Stamboul: Souvenir d’Orient (1861): Published in Paris by Lemercier, this album contained 29 chromolithographs based on Preziosi's watercolors. It presented a panorama of Constantinopolitan life, featuring iconic landmarks like the Hagia Sophia and the Sultan Ahmed Mosque (Blue Mosque), views of the Bosphorus, scenes from the bazaars, and depictions of various Ottoman figures in traditional attire. The album was immensely popular, solidifying Preziosi's reputation in Europe as a leading visual interpreter of the Ottoman capital.

Souvenir du Caire (c. 1862): Following a trip to Egypt around 1862, Preziosi produced a similar album focused on Cairo. This collection captured the unique atmosphere of the Egyptian capital, including its bustling markets (khan el khalili), street scenes, and historical monuments. Like its Istanbul counterpart, Souvenir du Caire catered to the European fascination with the East and showcased Preziosi's skill in rendering diverse environments.

Beyond these albums, specific individual works highlight his talent and typical subjects:

The Grand Bazaar: Preziosi painted numerous scenes within this sprawling, labyrinthine market, capturing the vibrant commerce, the diverse crowds, and the exotic goods on display. These works are noted for their detail and lively atmosphere.

The Silk Bazaar: Similar to his depictions of the Grand Bazaar, these paintings focus on specific sections of the market, emphasizing the textures and colors of the textiles being traded.

The Galata Bridge: Spanning the Golden Horn, this bridge was a vital artery of the city and a microcosm of its diverse population. Preziosi depicted it multiple times, capturing the flow of pedestrians, carriages, and boats against the backdrop of the city skyline, often including views of the Galata Tower or the mosques of the old city.

His work also included portraits and specific figure studies, often focusing on the details of costume and social types. He received prestigious commissions, including reportedly painting official portraits for the Ottoman court. Sources suggest he worked for Sultan Abdülaziz and later perhaps produced works collected by Sultan Abdülhamid II, indicating his high standing within the Ottoman capital itself.

Artistic Style: Neoclassicism Meets Romantic Orientalism

Preziosi's artistic style is a fascinating blend of the influences he absorbed. From his Neoclassical training at the École des Beaux-Arts, he retained a commitment to precise drawing, clarity of form, and attention to detail. This is evident in his meticulous rendering of architecture, ornamentation, and the specific features of clothing and objects. His compositions are often well-structured, providing a clear and ordered view of complex scenes.

However, his subject matter and atmospheric treatment place him firmly within the Orientalist movement, which was closely allied with Romanticism. The Romantic emphasis on emotion, exoticism, individualism, and the power of nature (or, in this case, culture) resonated strongly with European artists depicting the East. Preziosi's choice of subjects—the picturesque decay, the vibrant street life, the perceived sensuality or mystery of the Orient—aligns with common Orientalist tropes.

His use of color, particularly in watercolor, adds a layer of Romantic sensibility. While accurate, his palette often emphasizes the richness and vibrancy of the scenes, enhancing their exotic appeal. He masterfully captured the unique light of the Mediterranean and the Near East, contributing significantly to the mood and atmosphere of his works. His art, therefore, represents a bridge: the discipline of Neoclassicism applied to the evocative, often romanticized subjects of Orientalism. He documented reality but filtered it through an aesthetic lens shaped by European artistic conventions and cultural perceptions of the East.

Life in Pera: Family and Society

Amadeo Preziosi fully integrated into the life of Constantinople, particularly within the cosmopolitan milieu of Pera. Unlike artists on brief tours, he established a home and family there. He married a local Greek woman from Constantinople, whose name is often cited as Christina Psalti or similar variations. Together, they had four children: Mathilde, Giulia, Roberto, and Amadeo (sometimes referred to as Amedeo the Younger, who also became a painter, though less famous).

His family life connected him more deeply to the local community, bridging the gap between his European origins and his adopted home. His household likely reflected this blend of cultures. Living and working in Pera for four decades allowed him to witness significant changes in the city during the Tanzimat era of Ottoman reforms, although his art tended to focus more on the timeless or traditional aspects of life rather than overt political or social commentary.

His studio remained a focal point, not just for producing art but also for social interaction. He moved within the circles of diplomats, foreign residents, and likely interacted with Ottoman officials and intellectuals interested in the arts. His position as a respected artist from a noble European background would have granted him access to various levels of society, enriching his understanding and the scope of his potential subjects.

Context: Preziosi Among Orientalist Painters

Amadeo Preziosi was part of a larger wave of European artists drawn to the Ottoman Empire and the wider "Orient" in the 19th century. Understanding his work requires placing it within this broader context of Orientalism. This movement was diverse, encompassing artists with different motivations, styles, and levels of engagement with the cultures they depicted.

Preziosi's contemporaries or near-contemporaries who also focused on Ottoman or Eastern subjects included:

Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824-1904): A highly successful French academic painter, famous for his meticulously detailed, often dramatic, and sometimes controversial scenes of North Africa and the Ottoman world.

John Frederick Lewis (1804-1876): An English painter who lived in Cairo for a decade, known for his incredibly detailed watercolors and oil paintings of Egyptian domestic life, particularly harem scenes rendered with ethnographic precision.

David Roberts (1796-1864): A Scottish painter renowned for his topographical views and architectural studies from his travels in Egypt and the Near East, widely disseminated through lithographs.

Alberto Pasini (1826-1899): An Italian painter who traveled extensively in Persia, Turkey, and the Middle East, known for his vibrant, light-filled scenes of markets, caravans, and cityscapes.

Stanisław Chlebowski (1835-1884): A Polish painter who, like Preziosi, spent significant time in Constantinople, serving as court painter to Sultan Abdülaziz from 1864 to 1876. His work often focused on Ottoman history and military subjects.

Fausto Zonaro (1854-1929): An Italian painter who became the last official court painter to the Ottoman Sultan Abdülhamid II, arriving in Istanbul later than Preziosi but continuing the tradition of European artists documenting the city.

Osman Hamdi Bey (1842-1910): A pivotal figure, an Ottoman intellectual, archaeologist, and painter trained in Paris (under Gérôme). Unlike European Orientalists, he depicted Ottoman life from an insider's perspective, often challenging Western stereotypes while employing European techniques. His work provides a crucial counterpoint to artists like Preziosi.

Luigi Mayer (c. 1755-1803): An earlier Italian-German artist whose detailed views of the Ottoman Empire were influential.

Antoine Ignace Melling (1763-1831): A Franco-German architect and artist who served Sultan Selim III and produced stunning engravings of Constantinople.

Thomas Allom (1804-1872) & William Bartlett (1809-1854): British artists whose topographical views of Constantinople and the Ottoman Empire were widely popularized through engravings in travel books.

Salvatore Valeri (1856-1946): An Italian painter who arrived in Istanbul later in Preziosi's life but became a prominent teacher and painter of Istanbul scenes, continuing the Orientalist tradition into the early 20th century.

While direct collaboration or documented rivalry between Preziosi and many of these figures (especially those not based in Istanbul simultaneously, like Gérôme or Lewis) is scarce, they operated within the same artistic and cultural milieu. They shared patrons, audiences, and often subject matter, contributing collectively to the European visual construction of the Orient. Preziosi's unique contribution lies in his long-term residency, his focus on watercolor, and his specific blend of detailed observation and atmospheric rendering of Constantinople.

Reception, Criticism, and Legacy

During his lifetime, Amadeo Preziosi enjoyed considerable success. His works were exhibited in major European capitals like Paris and London, receiving positive attention. His patrons included European tourists, diplomats, and even the Ottoman court itself. The popularity of his lithograph albums further cemented his fame, making his vision of Constantinople accessible to a broad public. He was arguably the most sought-after painter in Constantinople for capturing the essence of the city for foreign visitors.

In subsequent art historical evaluation, Preziosi is recognized as a key figure among the Orientalist painters who specialized in the Ottoman world. His works are valued for their aesthetic quality, technical skill, and, importantly, as historical documents. They provide invaluable visual information about 19th-century Istanbul's architecture, costumes, customs, and urban environment during a period of significant transformation. Museums like the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the Louvre in Paris, the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, and various collections in Turkey hold his works.

However, like much Orientalist art, Preziosi's work has also been subject to critique through the lens of post-colonial theory, notably influenced by Edward Said's seminal work "Orientalism" (1978). Critics argue that Orientalist painting, even when seemingly documentary, often perpetuated stereotypes, exoticized or feminized the East, and reinforced notions of Western superiority. Preziosi's focus on the picturesque, the traditional, and sometimes the decaying aspects of Ottoman life could be interpreted as fitting within this framework, presenting a vision tailored to European tastes and expectations, potentially overlooking the complexities and modernization efforts within Ottoman society.

Furthermore, the question of his identity—a Maltese noble deeply embedded in depicting Ottoman culture—adds another layer. Was he an objective observer, a sympathetic participant, or a European artist catering to a market fascinated by otherness? His long residency suggests a deeper connection than that of a passing tourist, yet his perspective remained inevitably that of an outsider, albeit a highly informed one.

Despite these critical perspectives, Preziosi's art retains its power and value. His paintings and prints continue to be sought after by collectors, with works achieving significant prices at auction. For instance, a version of his Galata Bridge fetched £51,650 at Sotheby's in 2011, demonstrating the enduring market appeal. His legacy lies in the rich, detailed, and evocative visual record he created of a specific time and place, a record that remains essential for understanding both 19th-century Ottoman culture and the complex history of European artistic engagement with the East.

Final Years and Tragic End

Amadeo Preziosi remained active as an artist in Constantinople until his death. His end came unexpectedly and tragically. On September 27, 1882, while hunting, he suffered an accident involving his firearm. Reports indicate he accidentally shot himself, sustaining injuries that proved fatal. He passed away in San Stefano (modern Yeşilköy), a village on the outskirts of Istanbul where wealthy residents often had summer homes.

He was buried in the Catholic cemetery of Yeşilköy, marking the end of a life dedicated to bridging cultures through art. His death occurred just as the Ottoman Empire was entering a period of further upheaval and transformation, making his body of work capturing the mid-19th century city even more historically poignant.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision

Amadeo Preziosi's life journey took him from the aristocratic circles of Malta to the heart of the Ottoman Empire. Driven by artistic passion, he became one of the most prominent visual chroniclers of 19th-century Constantinople. His meticulous watercolors and popular prints captured the city's unique blend of grandeur and intimacy, its diverse peoples, and its vibrant daily rhythms. While situated within the complex and sometimes criticized tradition of Orientalism, his long immersion in the city and his detailed, atmospheric style lend his work a particular depth and authenticity.

Today, Preziosi's art serves multiple purposes: it delights the eye with its technical brilliance and aesthetic charm, it informs historians and researchers about a bygone era, and it prompts ongoing reflection about cultural representation and the relationship between West and East. As a Maltese nobleman who found his true subject in the bustling streets and scenic vistas of the Ottoman capital, Amadeo Preziosi left an indelible mark on the history of art, offering a vision of the Orient that continues to resonate.