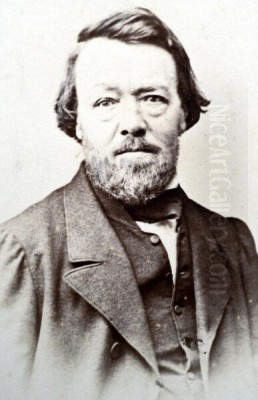

Auguste Borget (1809-1877) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in 19th-century French art. He was an artist whose life and work were inextricably linked to his extensive travels, capturing the essence of far-flung lands for a European audience increasingly curious about the wider world. Primarily known for his evocative paintings and prints of China, Borget was a meticulous observer and a skilled draftsman, whose contributions offer invaluable visual records of cultures and landscapes undergoing profound change. His art, while rooted in the traditions of his time, provides a unique window into the European encounter with the "Orient" and the Americas during a pivotal era of global exploration and exchange.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in France

Born in Issoudun, a town in central France, in 1809, Auguste Borget's early artistic inclinations led him to study under the painter Jean-Antoine-Siméon Fort, though some sources also mention a painter named Guédin as an early instructor. Like many aspiring artists of his generation, he would have been exposed to the prevailing artistic currents in Paris, a city that was the undisputed center of the European art world. The early 19th century was a dynamic period, with Neoclassicism, championed by artists like Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, gradually giving way to the emotional fervor and exoticism of Romanticism, famously embodied by Eugène Delacroix and Théodore Géricault.

During these formative years, Borget developed a close and lasting friendship with one of France's literary giants, Honoré de Balzac. This connection to the literary world was not uncommon for artists of the period and likely provided Borget with intellectual stimulation and a broader cultural perspective. Balzac himself was a keen observer of society, and this shared interest in documenting the world around them, albeit through different mediums, may have been a cornerstone of their friendship. Borget also maintained a close bond with Zulma Carraud, another notable literary figure and a mutual friend of Balzac, further embedding him within a circle of creative and intellectual individuals.

While details of his early artistic output before his major travels are less documented, it is clear that he was honing his skills in drawing and painting, preparing for a career that would soon take him far beyond the borders of France. The allure of distant lands, a sentiment fueled by Romantic literature and the increasing accessibility of global travel, began to beckon.

The Grand Tour Reimagined: Voyages Across Continents

The traditional "Grand Tour" for European artists and aristocrats had long focused on Italy and the classical antiquities. However, by the 19th century, the scope of desirable travel destinations had expanded dramatically. Borget embarked on his own version of a grand tour, one that would span continents and last for several years, beginning in the mid-1830s. His journeys were not merely for leisure; they were expeditions of artistic discovery, aimed at gathering firsthand material for his work.

His travels first took him across the Atlantic to the Americas. In 1837, he was in South America, where he created works such as Near Mendoza, capturing the rugged landscapes of Argentina. He also visited North America, producing prints like Windmill on the banks of Hudson River, New York, showcasing his ability to adapt his observational skills to diverse environments, from the burgeoning urbanity of the New World to its more pastoral scenes. These early travels provided him with a wealth of sketches and experiences, broadening his artistic palette and preparing him for the even more culturally distinct environments he would soon encounter in Asia.

This period of travel was crucial in shaping Borget's artistic identity. He became, in essence, a "travel painter," an artist whose primary subject matter was derived from direct observation of foreign lands and peoples. This genre was gaining popularity, as artists like David Roberts were achieving fame with their depictions of Egypt and the Near East, feeding a public appetite for the exotic and the picturesque.

The Asian Odyssey: Immersion in the East

In 1838, Auguste Borget embarked on the leg of his journey that would most define his artistic legacy: his voyage to Asia. This was a more ambitious undertaking, taking him to regions that were still relatively mysterious to many Europeans. His itinerary included key trading posts and cultural centers such as Singapore, Manila in the Philippines, and Calcutta (now Kolkata) in India. Each stop offered new sights, sounds, and cultural experiences, all of which Borget diligently recorded in his sketchbooks.

His time in Asia was not a fleeting visit. He immersed himself in these environments, seeking to understand and depict them with a degree of authenticity. His approach was that of an explorer-artist, keen to document not just the grand vistas but also the details of daily life, architecture, and local customs. This dedication to firsthand observation set him apart and lent a particular credibility to his later works.

The sketches and watercolors he produced during this period formed the raw material for the more finished paintings and prints he would create upon his return to Europe. These initial impressions, captured on the spot, retained a freshness and immediacy that would translate effectively into his studio compositions.

China: A World Unveiled

The centerpiece of Borget's Asian travels was undoubtedly his time in China. He arrived in 1838 and spent a significant period, nearly ten months, primarily in and around Canton (Guangzhou), the main port open to foreign trade at the time. He also visited the Portuguese enclave of Macau and the nascent British settlement of Hong Kong.

China in the late 1830s was on the cusp of immense upheaval, with the First Opium War looming. Borget's visit, therefore, provides a snapshot of the Pearl River Delta region just before this transformative conflict. He was fascinated by what he saw, from the bustling river life of Canton, with its myriad boats and distinctive architecture, to the unique blend of Chinese and European influences in Macau.

His work from this period demonstrates a keen eye for detail. He depicted temples, such as the famed Hoi Tong Monastery (Haichuang Temple or Sea-screen Temple) in Honam, Canton, street scenes, bustling marketplaces, and the diverse array of people he encountered. He was particularly interested in the everyday life of the Chinese, capturing scenes of labor, leisure, and religious practice. One notable observation he recorded was the discovery of vast bamboo aqueducts used for irrigation in the Pearl River Delta, a testament to local ingenuity.

Macau: An Artistic Haven and the Influence of George Chinnery

During his stay in Macau, Borget had a pivotal encounter with the British artist George Chinnery (1774-1852). Chinnery was an established figure in the expatriate art scene of India and China, known for his portraits of merchants and officials, as well as his lively sketches of local life in Macau and Canton. He had been residing in Macau for several years by the time Borget arrived.

The interaction with Chinnery proved to be highly beneficial for Borget. He learned from the more experienced artist, particularly in the realms of landscape painting and portraiture. Chinnery's fluid brushwork and his ability to capture the atmosphere of a scene likely influenced Borget's own developing style. This mentorship, or at least collegial exchange, helped Borget refine his techniques and deepen his understanding of how to translate the vibrant, complex reality of China into compelling visual art. The artistic community in Macau, though small, also included Chinese artists like Lam Qua, who adapted Western painting techniques to cater to the tastes of both Chinese and Western patrons, creating a unique artistic melting pot.

Borget's depictions of Macau are among his most celebrated works. He captured the unique colonial architecture, such as the area around St. Dominic's Church, and the busy scenes of the Inner Harbour with its fishing junks. A notable work is the Historical Painting in Front of the Main Hall of the Great Temple of Macau (referring to the A-Ma Temple), which was later produced as a lithograph. These images convey a sense of place that is both accurate and artistically engaging.

Hong Kong: Documenting a Nascent Port

Borget also visited Hong Kong in 1838, just a few years before it was formally ceded to Britain. At this time, it was still a relatively undeveloped area. His painting, Bay and Island of Hong Kong (1838), offers a valuable early visual record of the island's natural beauty, depicting a tranquil bay with figures on the shoreline against a backdrop of rolling hills. Such works are historically significant as they predate the extensive urbanization that would later transform the landscape. His depictions provide a baseline against which the rapid development of Hong Kong in the subsequent decades can be measured.

India: The Final Asian Leg

After his extensive stay in China, Borget continued his journey to India, visiting Calcutta, another major hub of the British Empire in the East. While his Indian works are perhaps less numerous or less frequently discussed than his Chinese scenes, they nonetheless form an important part of his travelogue. India, with its own rich tapestry of cultures, ancient monuments, and vibrant street life, would have offered a different but equally compelling array of subjects for his brush and pen. Artists like Thomas Daniell and William Daniell had earlier established a tradition of British artists depicting India, and Borget's visit contributed to this broader European artistic engagement with the subcontinent.

Return to Paris and Artistic Recognition

Auguste Borget returned to Paris in 1840, his portfolios filled with sketches, watercolors, and invaluable memories from his years abroad. He began the process of translating these field studies into finished oil paintings and, significantly, into lithographs for wider dissemination. From 1836 until 1859, he regularly exhibited his works at the prestigious Paris Salon, the official art exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts, which was the primary venue for artists to gain recognition and patronage.

His depictions of exotic locales, particularly those of China, resonated with the Parisian public and critics. The interest in "Orientalism" – the depiction of Eastern subjects by Western artists – was at its height, fueled by colonial expansion, increased trade, and romantic notions of distant cultures. Artists like Delacroix, with his North African scenes, and Ingres, with his odalisques, had already popularized Orientalist themes, though Borget's approach was often more documentary and less overtly romanticized than some of his contemporaries.

Borget's work received positive attention, and he gained a degree of fame for his unique subject matter. His paintings were admired for their detailed observation and the sense of authenticity they conveyed. Importantly, some of his works were acquired by the French royalty, including King Louis-Philippe I, which was a significant mark of official approval and enhanced his reputation.

La Chine et les Chinois: A Landmark Publication

One of Borget's most enduring contributions was his illustrated travelogue, La Chine et les Chinois (China and the Chinese), published in Paris in 1842. This lavishly produced volume featured numerous lithographs based on his on-site drawings, with the skilled printmaker Eugène Ciceri (sometimes spelled Cericelli) responsible for translating many of Borget's original sketches into high-quality, often hand-colored, lithographs.

La Chine et les Chinois was more than just a collection of pictures; it was accompanied by Borget's own written account of his travels and observations. It is considered the first travel diary about China written in French by an artist who had spent considerable time there. The book offered an unprecedented visual and textual immersion into Chinese life and culture for the French-speaking world. It showcased the landscapes, architecture, customs, and people Borget had encountered, from street vendors and monks to mandarins and boat dwellers.

The publication of this book, along with a similar volume titled Sketches of China and the Chinese (which may refer to an English edition or a collection of prints), solidified Borget's reputation as an expert on China and a leading travel artist. These publications made his work accessible to a broader audience beyond those who could attend the Salon or purchase original paintings, significantly contributing to the European visual understanding of China in the mid-19th century.

Artistic Style, Themes, and Techniques

Auguste Borget's artistic style can be characterized by a blend of Romantic sensibility and Realist observation. While the choice of exotic subject matter aligns with Romanticism's fascination with the distant and unfamiliar, his execution often displays a commitment to accurate depiction reminiscent of Realism, a movement that was gaining traction with artists like Gustave Courbet and Jean-François Millet, though Borget's focus was different.

His primary strength lay in his draftsmanship and his ability to capture the specific details of architecture, costume, and environment. His lines are often described as simple yet effective, conveying form and texture with clarity. He was adept at rendering complex scenes with numerous figures and intricate architectural elements without losing overall coherence. His use of color, particularly in his watercolors and hand-colored lithographs, was often subtle and harmonious, aiming for naturalism rather than overt drama.

Thematically, Borget's work revolved around the documentation of foreign cultures. He was an ethnographer with a sketchbook, recording not just picturesque views but also aspects of social life, religious practices, and economic activities. His interest extended from grand temples and palaces to humble dwellings and bustling street markets. He depicted modes of transport, types of labor, and forms of entertainment, providing a rich visual tapestry of the societies he visited.

In terms of technique, Borget was versatile. He produced oil paintings, which allowed for richer colors and more finished compositions suitable for Salon exhibitions. However, a significant portion of his output consisted of watercolors and drawings, which were ideal for capturing immediate impressions during his travels. The translation of these works into lithographs, often with delicate hand-coloring, was crucial for their dissemination and impact. Lithography, a relatively new printmaking technique at the time, allowed for a high degree of fidelity to the original drawing and could be produced in larger quantities.

Borget and the Parisian Art World: Connections and Context

While Borget carved out a niche for himself as a travel artist, he operated within the broader context of the Parisian art world. His friendship with Balzac connected him to literary circles. His regular participation in the Paris Salon placed him in dialogue, however indirect, with the leading artists of his day.

There is no direct evidence of close personal or artistic collaboration between Borget and major figures like Eugène Delacroix or Gustave Courbet. Delacroix, the standard-bearer of Romanticism, was renowned for his dramatic compositions and expressive use of color, often drawing inspiration from literature, history, and his own travels in North Africa (e.g., Women of Algiers in their Apartment). Courbet, on the other hand, became the provocative leader of the Realist movement, challenging academic conventions with his unidealized depictions of rural life and contemporary social issues (e.g., The Stone Breakers, A Burial at Ornans).

While Borget may not have shared their specific artistic agendas or revolutionary zeal, he was undoubtedly aware of their work and the broader artistic debates of the time. The prevailing interest in Orientalism, to which Delacroix was a key contributor, certainly created a receptive environment for Borget's own exotic subjects. Similarly, the growing emphasis on direct observation and the depiction of contemporary life, central to Realism, found an echo in Borget's commitment to documenting what he saw on his travels. His work can be seen as a specific application of Realist principles to the genre of travel art.

Other artists were also engaged in depicting foreign lands. In Britain, artists like Thomas Allom and, earlier, William Alexander (who accompanied the Macartney Embassy to China), produced influential images of China. Borget's work stands alongside theirs, offering a French perspective. The Barbizon School painters, such as Camille Corot and Théodore Rousseau, were contemporaneous, focusing on realistic depictions of the French countryside, emphasizing a different kind of "truth to nature." Even an artist like Horace Vernet, known for his battle scenes, also produced Orientalist works. Borget's unique contribution was his extensive firsthand experience in a wide range of non-European settings, particularly his in-depth engagement with China.

Challenging Perceptions: A Nuanced View of the East

One of the more interesting aspects of Borget's legacy is his relatively nuanced and respectful portrayal of non-European cultures, particularly Chinese culture. At a time when European colonial ambitions were often accompanied by a sense of cultural superiority and stereotypical, often derogatory, depictions of "Orientals," Borget's work frequently emphasized the beauty, order, and sophistication he observed.

In La Chine et les Chinois, he expressed views that challenged some of the prevailing European prejudices. He suggested that there were many similarities in cultural and spiritual values between China and the West, and he was clearly impressed by the industry, artistry, and social organization he witnessed. While his perspective was inevitably that of a 19th-century European, his efforts to understand and represent Chinese culture with a degree of empathy and accuracy were noteworthy. This approach lends his work an enduring value beyond its purely aesthetic or picturesque qualities.

Anecdotes and Notable Incidents

Borget's life as a traveler-artist was undoubtedly filled with memorable encounters and experiences. His tutelage under George Chinnery in Macau was a significant professional turning point. His detailed sketches of specific locations, like the shops near St. Dominic's Church or the boatyards of Macau's Inner Harbour, speak to a patient and observant character, willing to spend time absorbing the local atmosphere.

The very act of traveling to such distant and, at times, challenging environments in the 1830s was an adventure in itself. He navigated different languages, customs, and climates, all while maintaining his artistic practice. His discovery and documentation of the large bamboo water channels in the Pearl River Delta highlight his curiosity and his eye for the unique and ingenious aspects of the cultures he visited.

While not marked by major public controversies in the way some of his more politically engaged contemporaries like Honoré Daumier or Courbet were, Borget's quiet dedication to his craft and his respectful engagement with foreign cultures can be seen as a form of cultural diplomacy, fostering understanding through art.

Legacy and Museum Collections

Auguste Borget's legacy rests on his significant contribution to the European visual understanding of China and other parts of Asia and the Americas in the mid-19th century. His works are valuable not only for their artistic merit but also as historical documents, capturing landscapes and ways of life that have since been profoundly altered or have disappeared altogether.

His paintings, watercolors, and prints are held in several important museum collections, reflecting the geographical scope of his travels and the regions where his work has been most appreciated.

Key institutions include:

Hong Kong Museum of Art: This museum holds a significant collection of Borget's works related to the region, including pieces like Sea-screen Temple (Hoi Tong Monastery) and depictions of early Hong Kong and Macau, such as Historical Painting in Front of the Main Hall of the Great Temple of Macau.

Macao Museum of Art: Given Borget's extensive work in Macau and his connection with Chinnery, this museum also houses important examples of his art, particularly those depicting the A-Ma Temple and other local scenes.

Peabody Essex Museum (Salem, Massachusetts, USA): This museum, with its rich collections related to maritime trade and global cultures, holds works by Borget, including an 1838 depiction of Honolulu, titled Honolulu Salt Pan, near Kakaʻako, reflecting his Pacific travels.

While specific holdings in major European national museums like the Louvre (which would have been a contemporary institution) are less prominently cited for Borget compared to artists like Delacroix, his works were, as noted, acquired by French royalty and exhibited at the Salon, indicating their contemporary importance in France. His prints, disseminated through publications like La Chine et les Chinois, ensured a wider reach.

Conclusion: An Artist Bridging Worlds

Auguste Borget was more than just a painter of pretty pictures from faraway lands. He was an intrepid explorer, a careful observer, and a skilled artist who dedicated a significant part of his life to documenting the diverse cultures and landscapes he encountered on his global travels. His work, particularly his detailed and empathetic depictions of China in the years leading up to the Opium Wars, provides an invaluable visual record of a world on the brink of dramatic change.

He successfully navigated the artistic currents of his time, blending elements of Romanticism and Realism to create a body of work that appealed to the 19th-century European fascination with the exotic, while also offering a degree of ethnographic accuracy. Through his paintings, and especially through his widely circulated lithographs and illustrated books, Borget played a crucial role in shaping Western perceptions of China and other distant regions. His legacy endures in the collections of museums that prize his unique contribution to the art of travel and cross-cultural representation, reminding us of a time when artists were among the primary conduits for understanding a rapidly globalizing world.