Andrea Marchisio (1850-1927) stands as a notable figure in the artistic landscape of late 19th and early 20th-century Italy, particularly within the vibrant cultural milieu of Turin. A painter whose oeuvre spanned detailed historical genre scenes, evocative landscapes, and later, the luminous artistry of stained glass, Marchisio carved a distinct niche for himself. His work reflected both the academic traditions in which he was trained and a personal inclination towards the meticulous rendering of bygone eras, especially the perceived elegance and charm of the 18th century. His contributions, though perhaps not as internationally heralded as some of his contemporaries, were significant within his regional context and offer a valuable insight into the artistic currents of Piedmont during a period of profound social and cultural transformation.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Turin

Born in Turin in 1850, Andrea Marchisio came of age in a city that was not only a political powerhouse in the newly unified Italy but also a significant center for artistic education and production. His formal artistic training took place at the prestigious Accademia Albertina di Belle Arti in Turin, an institution that had long been the cornerstone of artistic instruction in the region. Here, he studied under the guidance of influential painters such as Enrico Gamba (1831-1883) and Andrea Gastaldi (1826-1889). Both Gamba, known for his historical and battle scenes, and Gastaldi, a leading figure in Italian Romantic painting with a penchant for historical and literary subjects, would have instilled in Marchisio a strong foundation in academic drawing, composition, and the thematic importance of history painting.

The academic environment of the Accademia Albertina, like many European art academies of the time, emphasized rigorous training in drawing from life and from classical casts, a thorough understanding of perspective and anatomy, and the study of Old Masters. This traditional curriculum aimed to equip artists with the technical proficiency necessary to tackle complex figural compositions and grand historical narratives. Marchisio's later precision and attention to detail in his genre scenes undoubtedly owe much to this formative academic grounding. His early career also saw him take on an academic role himself; in 1866, he was noted as an assistant professor at the Albenga Academy, though his primary association remained with the Turin art world.

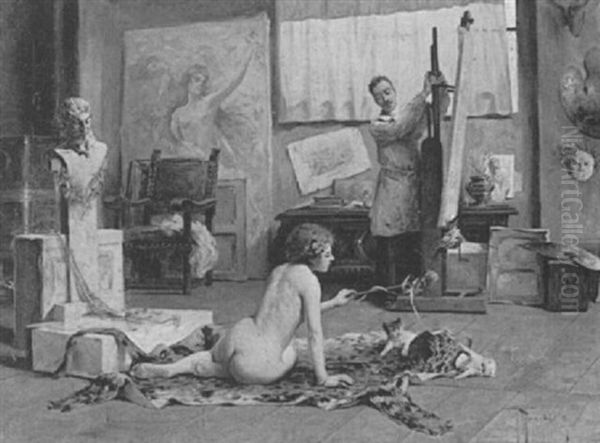

The Allure of the Ancien Régime: Historical Genre Paintings

Marchisio's reputation as a painter was significantly built upon his historical genre scenes, particularly those evoking the Rococo grace and aristocratic lifestyles of the 18th century. This fascination with the Ancien Régime was not unique to Marchisio; it was a recurring theme in 19th-century European art, often reflecting a nostalgic yearning for a perceived era of greater elegance and refinement, or serving as a picturesque backdrop for storytelling. Artists like Jean-Louis-Ernest Meissonier in France, with his incredibly detailed depictions of 17th and 18th-century life, or the Spaniard Mariano Fortuny, whose dazzling technique captured the opulence of similar periods, had set a high bar for this type of painting, and the taste for such works was widespread among bourgeois collectors.

Andrea Marchisio's contributions to this genre are exemplified by his celebrated work, Scena galante in abiti settecenteschi (Gallant Scene in Eighteenth-Century Attire), painted in 1884. This oil on canvas, measuring a significant 171 x 121 cm, showcases his mastery in recreating the atmosphere of an aristocratic salon or ballroom. The painting is characterized by its meticulous attention to detail, from the lustrous fabrics of the elaborate costumes to the ornate furnishings and architectural elements of the interior. Marchisio's figures, often poised and graceful, engage in polite social interactions, capturing the spirit of Rococo elegance. Such works were not merely decorative; they invited viewers to immerse themselves in a romanticized past, offering an escape from the rapidly industrializing present. The success of these paintings lay in their ability to combine historical accuracy, or at least a convincing semblance of it, with a pleasing aesthetic and narrative charm. This particular masterpiece found its place in a Turin museum, underscoring its recognition and importance within the local art scene.

His dedication to historical accuracy, or at least the convincing portrayal of historical settings, required considerable research into costume, manners, and interior design of the period. This scholarly approach, combined with a refined painterly technique, allowed Marchisio to create vivid and engaging scenes that appealed to the tastes of his patrons. The figures in these paintings are often characterized by their delicate features and elegant postures, embodying the idealized social graces of the 18th century. The interplay of light and shadow, the rich color palettes, and the careful composition all contribute to the overall effect of opulence and sophistication.

Expanding Horizons: Landscapes and Other Subjects

While Marchisio was renowned for his 18th-century genre scenes, his artistic interests were not solely confined to powdered wigs and silk brocades. He also ventured into landscape painting and other subjects, demonstrating a broader range of skills and sensibilities. One such example is Paesaggio con stalliere e cavalli (Landscape with Groom and Horses), also dated to 1884. This oil painting, smaller in scale at 45.5 x 66 cm, reveals a different facet of his artistry. Here, the focus shifts from the enclosed, artificial elegance of the salon to the more natural, rustic charm of the outdoors. The depiction of horses and figures within a landscape setting would have required a keen observational skill and an understanding of animal anatomy, as well as the ability to capture the nuances of natural light and atmosphere.

Another work attributed to him, though the title La corna blacca con i monti Frondite e Tegaldino seems somewhat specific and perhaps refers to a particular Alpine or regional view, further suggests his engagement with landscape. If this title refers to a mountain landscape, it would place him within a strong Piedmontese tradition of Alpine painting, a genre that was particularly popular in Turin, given its proximity to the Alps. Artists like Antonio Fontanesi (1818-1882), a leading landscape painter and influential teacher at the Accademia Albertina, had already established a powerful school of landscape painting in the region, characterized by its atmospheric depth and poetic sensibility. While Marchisio's primary focus remained historical genre, these excursions into landscape demonstrate his versatility and his connection to broader artistic trends in Piedmont.

The techniques employed in these varied subjects would have remained rooted in his academic training, emphasizing careful drawing, balanced composition, and a controlled application of paint. However, landscape painting often allowed for a slightly looser brushwork and a more direct engagement with the effects of light and color as observed in nature, potentially offering a contrast to the highly finished surfaces typical of his historical interiors.

A Luminous Transition: The Art of Stained Glass

A significant development in Andrea Marchisio's career occurred in the 1880s, or possibly extending into the 1890s, when he increasingly turned his attention to the art of stained glass. This shift represents a fascinating expansion of his artistic practice, moving from the opaque medium of oil paint on canvas to the translucent, light-filled world of colored glass. Stained glass work, particularly for ecclesiastical settings, was experiencing a revival in the 19th century, partly fueled by the Gothic Revival movement and a renewed interest in medieval arts and crafts. Creating designs for stained glass windows required a different set of skills and considerations than easel painting. The artist had to think in terms of transmitted light, the interplay of colors as they would be seen with light passing through them, and the structural requirements of leading and fitting the glass pieces.

Marchisio is known to have created stained glass windows for several churches in the Piedmont region. The records specifically mention his work for churches in Quarto (likely Quarto d'Asti or a similarly named locality in the area), Monferrato (a historical-geographical region of Piedmont famous for its wine and landscapes, encompassing many towns and churches), Cossano Canavese, and Camagna Monferrato. While detailed descriptions or images of these specific stained glass works are not readily available in common sources, their existence points to a significant body of work in this demanding medium. Ecclesiastical commissions for stained glass typically involved biblical scenes, depictions of saints, or symbolic religious imagery, all of which would need to be adapted to the unique visual language of glass.

This phase of his career highlights Marchisio's adaptability and his willingness to explore new artistic avenues. The creation of stained glass was often a collaborative effort, involving workshops and skilled artisans who would translate the painter's designs (cartoons) into the final glass panels. His involvement in this field connected him to a long tradition of sacred art and allowed his work to become an integral part of the architectural and spiritual environment of these churches, viewed by congregations for generations.

Marchisio in the Context of 19th-Century Italian Art

Andrea Marchisio's career unfolded during a dynamic period in Italian art. The unification of Italy (the Risorgimento) had a profound impact on national identity and cultural expression. In the realm of painting, various artistic currents coexisted and sometimes competed. The academic tradition, upheld by institutions like the Accademia Albertina, continued to be influential, promoting historical subjects, mythological scenes, and portraiture executed with technical polish. Marchisio, with his historical genre paintings, clearly operated within this sphere, albeit with a specific focus on the 18th century.

He was a regular contributor to the exhibitions of the Società Promotrice delle Belle Arti (Society for the Promotion of Fine Arts) in Turin. Founded in 1842, the Promotrice played a crucial role in the Turin art world, providing a platform for artists to showcase their work, fostering artistic debate, and facilitating sales. Marchisio's consistent participation from 1869 until the late 19th century indicates his active engagement with the city's artistic life and his recognized status among his peers.

During this period, Turin was home to many other significant artists. Besides his teachers Gamba and Gastaldi, and the landscape master Fontanesi, one could mention Giacomo Grosso (1860-1938), a highly successful portraitist and genre painter whose work often courted controversy but was immensely popular. While Grosso's style was often more flamboyant and psychologically charged than Marchisio's, they were part of the same Turinese art scene. Other Piedmontese artists of note included the landscape painter Lorenzo Delleani (1840-1908) and Vittorio Avondo (1836-1910), known for his historical romantic landscapes.

Beyond Piedmont, Italian art was diverse. The Macchiaioli in Tuscany, including figures like Giovanni Fattori (1825-1908), Telemaco Signorini (1835-1901), and Silvestro Lega (1826-1895), had pioneered a form of Italian Realism with their revolutionary "macchia" (spot or patch) technique, focusing on contemporary life and landscape. In Naples, Domenico Morelli (1826-1901) was a dominant figure, known for his dramatic historical and religious paintings with a Romantic and Realist bent. Later in the century, Divisionism, with artists like Giovanni Segantini (1858-1899) and Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo (1868-1907), brought a more scientific approach to color and light, often imbued with Symbolist themes. While Marchisio's work did not directly align with these more avant-garde movements, his dedication to historical genre and later to stained glass represented a valid and appreciated artistic path that catered to specific tastes and fulfilled important cultural and religious functions. His style can be seen as part of a broader European academic-realist tradition that continued to thrive alongside emerging modernist trends.

The international scene also saw artists like Giovanni Boldini (1842-1931) and Giuseppe De Nittis (1846-1884), Italians who found great success in Paris, embracing more impressionistic or Belle Époque styles. Marchisio, by contrast, seems to have remained more rooted in his native Turin, contributing to its specific artistic identity. His work, therefore, should be understood within this rich tapestry of local, national, and international artistic developments.

Legacy and Appreciation

Andrea Marchisio passed away in 1927, leaving behind a body of work that reflects the artistic tastes and academic standards of his time. His legacy is primarily that of a skilled historical genre painter with a particular affinity for the 18th century, and later, as a dedicated creator of stained glass for ecclesiastical spaces. His oil paintings, characterized by their detailed execution and elegant subject matter, found favor with collectors and earned him a place in public exhibitions and museum collections, such as the aforementioned Scena galante in Turin.

The shift to stained glass in the latter part of his career demonstrates an artistic versatility and a commitment to a craft that, while different from easel painting, required immense skill and artistic vision. These works, integrated into the architecture of churches in Piedmont, continue to fulfill their spiritual and aesthetic purpose, bathing sacred spaces in colored light and narrating religious stories to contemporary audiences, perhaps often anonymously to the casual observer but nonetheless part of the region's artistic heritage.

While Andrea Marchisio may not be a household name in the grand narrative of international art history, his contributions are significant within the context of 19th-century Italian and, more specifically, Piedmontese art. He represents a strand of academic painting that valued craftsmanship, historical evocation, and decorative elegance. His works serve as a window into the cultural preoccupations of his era, reflecting a nostalgia for the past and a dedication to artistic traditions that continued to hold sway even as modernism began to reshape the artistic landscape. The survival of his paintings in museum collections and the enduring presence of his stained glass in churches ensure that his artistic voice, characterized by meticulous detail and a quiet charm, continues to be appreciated. His career underscores the richness and diversity of artistic practice in late 19th-century Italy, a period of transition and vibrant creativity.