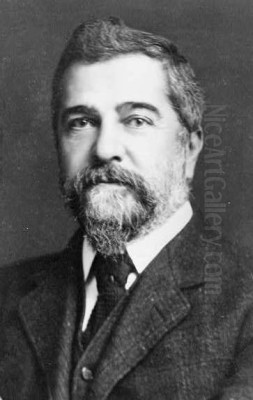

Louis Comfort Tiffany stands as one of the most influential and versatile figures in American art history. Born into the lap of luxury as the son of the founder of the renowned jewelry firm Tiffany & Co., he carved his own distinct path, moving beyond his family's legacy to become a master of decorative arts, particularly in the medium of glass. His name is synonymous with the opalescent stained-glass windows and luminous lamps that defined the Art Nouveau era in the United States. Yet, his artistic endeavors spanned painting, interior design, mosaics, metalwork, ceramics, and jewelry, all unified by a profound love of nature and an innovative spirit that pushed the boundaries of materials and craftsmanship.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Louis Comfort Tiffany was born in New York City on February 18, 1848. His father, Charles Lewis Tiffany, had established Tiffany & Co., a name already synonymous with luxury goods and fine jewelry. Growing up surrounded by beautiful objects and the burgeoning cultural scene of Gilded Age New York undoubtedly shaped young Louis's aesthetic sensibilities. However, rather than joining the family business directly, he felt the pull of fine arts, specifically painting.

His formal artistic training began under the tutelage of prominent American landscape painters. He studied with George Inness, known for his atmospheric and Tonalist landscapes, which likely instilled in Tiffany an appreciation for light and mood. He also studied with Samuel Colman, another respected landscape artist who later became a collaborator. Tiffany's early paintings reflected these influences, often depicting landscapes and scenes inspired by his travels.

Seeking broader horizons, Tiffany traveled to Europe and North Africa in the late 1860s and 1870s. In Paris, he briefly studied with the academic painter Léon-Adolphe-Auguste Belly. More significantly, his travels exposed him to the rich artistic traditions of Europe and the exotic allure of Islamic art and architecture in North Africa. The intricate patterns, vibrant colors, and light-filtering effects of Moorish design left a lasting impression, influencing his later work in decorative arts. He exhibited his paintings at venues like the National Academy of Design in New York (starting in 1867) and the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition in 1876, establishing himself as a capable painter within the American art scene.

The Pivot to Decorative Arts and Interiors

Despite achieving recognition as a painter, Tiffany felt a growing fascination with the decorative arts, particularly the potential of glass. Around the mid-1870s, his focus began to shift. He became increasingly interested in interior decoration, viewing it as a way to create unified, immersive artistic environments. This shift aligned with the burgeoning Aesthetic Movement and the subsequent Arts and Crafts movement, which emphasized the integration of art into everyday life and valued craftsmanship across different media.

In 1879, Tiffany took a decisive step by forming Louis C. Tiffany and Associated Artists. This interior decorating firm brought together a talented group of individuals, including Samuel Colman, Lockwood de Forest (an expert in East Indian crafts and design), and Candace Wheeler (a pioneer in textile design and applied arts for women). This collaborative venture aimed to provide clients with comprehensive, artistically conceived interiors, encompassing everything from furniture and textiles to lighting and stained glass.

The firm quickly gained prestigious commissions. They designed interiors for the homes of prominent figures like Mark Twain in Hartford, Connecticut, and the pharmaceutical magnate George Kemp. Perhaps their most high-profile project was the redecoration of several rooms in the White House in 1882-1883 for President Chester A. Arthur. The team incorporated elaborate patterns, rich textures, and, notably, Tiffany's innovative use of glass, including a massive, intricate colored glass screen in the Entrance Hall, demonstrating his burgeoning mastery of the medium. Although the Associated Artists firm was relatively short-lived, dissolving in 1883, it cemented Tiffany's reputation as a leading figure in American interior design and set the stage for his next, most enduring venture.

Tiffany Studios and the Magic of Favrile Glass

Following the dissolution of Associated Artists, Tiffany established his own firm, Tiffany Glass Company, in 1885 (later renamed Tiffany Studios in 1902). This company became the primary vehicle for his artistic vision, focusing heavily on the production of stained glass windows, lamps, mosaics, blown glass vessels, metalwork, jewelry, and enamels. Central to the studio's success and Tiffany's unique contribution to art history was his development of innovative glass types.

Dissatisfied with the quality and limitations of commercially available glass, Tiffany established his own glass furnaces and laboratory in Corona, Queens, New York. Here, he experimented relentlessly to achieve new colors, textures, and effects. His most famous invention was Favrile glass, patented in 1894. The name derived from the Old English word "fabrile," meaning "handmade." Favrile glass was characterized by its iridescent surface and brilliant, deeply saturated colors embedded within the glass itself, rather than painted on.

Tiffany achieved these effects by mixing different colors of molten glass together and incorporating metallic oxides that reacted to heat, creating shimmering, lustrous surfaces reminiscent of ancient Roman and Syrian glass, which he admired. Unlike traditional stained glass, which relied heavily on painting details onto the glass surface, Tiffany's approach used the inherent properties of the glass—its color, texture, opacity, and translucency—to create images and effects. He developed various types of Favrile glass, including "Lustre," "Cypriote" (mimicking the pitted texture of ancient glass), and "Lava" glass (with its volcanic, flowing appearance), expanding the expressive potential of the medium.

Masterworks in Stained Glass

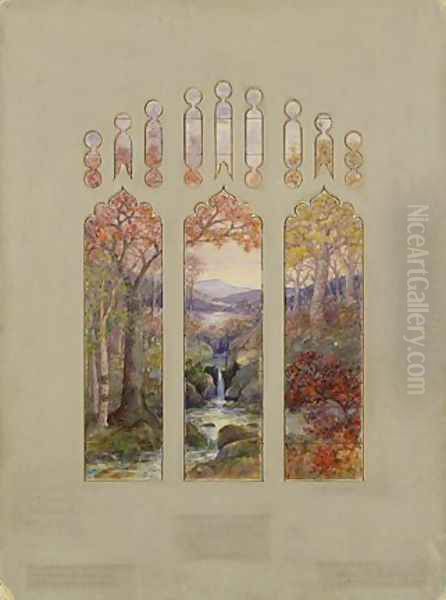

Tiffany Studios quickly became renowned for its ecclesiastical and secular stained-glass windows. Tiffany approached stained glass with a painter's eye, seeking to "paint with light." He moved away from the medieval revival style prevalent at the time, which often featured flat, graphic designs and extensive surface painting. Instead, he embraced a more naturalistic and pictorial style, heavily influenced by American landscape painting and Art Nouveau aesthetics.

His windows often depicted lush landscapes, floral motifs, or religious scenes rendered with remarkable depth and luminosity. He achieved this through the sophisticated use of his Favrile glass and innovative techniques. Opalescent glass, a milky, semi-opaque glass that diffused light beautifully, was a key element. Tiffany layered pieces of glass, sometimes several layers deep, to create subtle variations in color and tone. He also employed "drapery glass," thick sheets folded and manipulated while molten to simulate the folds of fabric, and "confetti glass," embedded with small, colorful flakes.

Notable examples of Tiffany Studios' window commissions include the vast "Education" window (1890) designed for the Yale University Library (now in the Yale University Art Gallery), depicting allegorical figures representing various fields of knowledge. His religious windows, such as "The Holy City" (1905) at Brown Memorial Presbyterian Church in Baltimore, Maryland, demonstrate his ability to convey spiritual themes through radiant color and light. He competed fiercely in this field, particularly with artist John La Farge, who was also experimenting with opalescent glass around the same time, leading to disputes over patents and artistic precedence. Despite the rivalry, both artists significantly advanced the art of stained glass in America.

The Iconic Tiffany Lamp

Perhaps the most widely recognized products of Tiffany Studios are the leaded glass lamps. Developed from the late 1890s onwards, these lamps combined functional lighting with exquisite artistry, becoming coveted symbols of taste and status during the Art Nouveau period. While Louis Comfort Tiffany oversaw the design aesthetic, much of the detailed design work for the lamps, particularly the shades, was carried out by a team of talented female designers known as the "Tiffany Girls," led by Clara Driscoll. Driscoll is now credited with designing many of the most famous patterns.

Tiffany lamp shades were constructed using the copper foil technique. Small pieces of Favrile and other types of colored glass were individually cut, edged with copper foil, and then soldered together to form intricate patterns. This method allowed for finer detail and more complex curves than traditional lead came techniques. The shades often featured motifs drawn directly from nature – dragonflies with iridescent filigree wings, clusters of wisteria blossoms cascading down the shade, vibrant peonies, poppies, and daffodils.

The lamp bases were typically cast in bronze and were often sculptural complements to the shades, featuring designs like tree trunks, lily pads, or geometric patterns. The combination of the richly colored, textured glass shade and the finely crafted base created objects of extraordinary beauty, transforming electric lighting from a mere utility into a decorative art form. Popular models like the "Wisteria," "Dragonfly," and "Peony" lamps remain highly sought after by collectors today, embodying the essence of Tiffany's style.

Expanding the Vision: Mosaics, Metalwork, and Jewelry

While glass remained central, Tiffany Studios excelled in various other media, reflecting Louis Comfort Tiffany's holistic approach to design. Mosaics were a significant part of their output, used for murals, fireplace surrounds, and architectural decoration. Tiffany adapted his glass techniques to mosaic work, using Favrile glass tesserae to create shimmering, painterly surfaces.

One of the most spectacular examples is "The Dream Garden" (1916), a massive mosaic mural based on a painting by Maxfield Parrish. Commissioned by the Curtis Publishing Company for their building lobby in Philadelphia, this breathtaking work comprises over 100,000 pieces of Favrile glass, depicting a mystical landscape with incredible luminosity and color gradation. It showcases the studio's technical virtuosity and Tiffany's ability to translate artistic visions into complex glass forms.

Metalwork was another important area. Tiffany Studios produced a wide range of functional and decorative objects in bronze, copper, and other metals, often finished with rich patinas. Desk sets, inkstands, picture frames, candlesticks, and decorative boxes featured motifs that echoed those found in the glasswork – natural forms, geometric patterns, and influences from Islamic and Byzantine art. These pieces often incorporated Favrile glass elements, such as iridescent panels or inset "jewels."

Tiffany also made significant contributions to jewelry design, distinct from the diamond-centric pieces of his father's company. Working with enamel and semi-precious stones alongside his signature Favrile glass, he created unique, handcrafted pieces inspired by nature and historical styles. Pendants, necklaces, and brooches often featured motifs like peacocks, dragonflies, or flowers, rendered in the flowing lines of Art Nouveau and showcasing innovative material combinations.

Laureltown Hall: A Total Work of Art

Tiffany's belief in the integration of art and life found its ultimate expression in his own estate, Laureltown Hall, built between 1902 and 1905 on a vast property in Oyster Bay, Long Island. This sprawling, 84-room mansion was conceived as a Gesamtkunstwerk – a total work of art – where architecture, interior design, furnishings, art objects, and landscape were harmoniously unified according to his vision.

The house itself was an eclectic blend of styles, incorporating elements of Moorish, Byzantine, and Art Nouveau design. Inside, rooms were lavishly decorated with Tiffany glass windows, mosaics, lamps, custom-designed furniture, textiles, and pieces from his extensive collection of Asian and Islamic art. The estate featured magnificent gardens, fountains, terraces, and even its own chapel, all designed by Tiffany. The famous Daffodil Terrace, with its columns topped by capitals made of iridescent Favrile glass resembling daffodils, exemplified his integration of nature and innovative materials.

Laureltown Hall served not only as his home but also as a showcase for his artistic ideals and the capabilities of Tiffany Studios. He established the Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation there in 1918, intending it as an artists' retreat. Sadly, changing tastes and financial pressures led to the foundation's decline after Tiffany's death. The mansion fell into disrepair and was largely destroyed by fire in 1957. However, significant elements, including windows, architectural features like the Daffodil Terrace columns, and furnishings, were salvaged and are now preserved in museum collections, most notably at the Charles Hosmer Morse Museum of American Art in Winter Park, Florida.

Artistic Style, Influences, and Collaborations

Louis Comfort Tiffany's style is most closely associated with Art Nouveau, the international design movement that flourished from the 1890s to the early 1910s. His work embodies many of its key characteristics: sinuous, organic lines inspired by nature, a rejection of rigid historical revivalism, and an emphasis on craftsmanship and the integration of different art forms. His use of floral and insect motifs, flowing forms, and iridescent surfaces aligns perfectly with Art Nouveau aesthetics seen in the work of European contemporaries like Émile Gallé in France.

However, Tiffany's style was also deeply rooted in the principles of the Arts and Crafts movement, with its emphasis on handcraftsmanship, the inherent beauty of materials, and the creation of unified, aesthetically pleasing environments. His lifelong fascination with nature was perhaps the most dominant influence, providing an endless source of motifs and color palettes. His travels also played a crucial role, with Islamic, Byzantine, and Asian art informing his sense of pattern, color, and material experimentation.

Throughout his career, Tiffany collaborated with numerous artists, designers, and architects. His early partnership in Associated Artists with Samuel Colman, Lockwood de Forest, and Candace Wheeler was formative. He worked with prominent architects like Stanford White on interior commissions. Within Tiffany Studios, he relied on talented designers like Clara Driscoll and chemists like Arthur J. Nash to realize his vision for lamps and glass formulas. His rivalry with John La Farge, though often contentious, spurred innovation in American stained glass. He also faced competition from other firms producing similar styles of lamps and glass, such as Duffner & Kimberly, founded by Frank Duffner (or Dufrane) and Oliver Kimberly.

International Acclaim and Later Years

Tiffany achieved significant international recognition during his lifetime. His exhibits at major world's fairs were highly acclaimed. At the 1900 Exposition Universelle in Paris, his display of Favrile glass vases, windows, and lamps was a sensation, earning him a gold medal and solidifying his reputation as a leading international figure in the decorative arts. His work was admired and collected across Europe.

Tiffany Studios reached the peak of its success and production in the first two decades of the 20th century. However, by the 1920s, artistic tastes began to shift away from the ornate naturalism of Art Nouveau towards the cleaner lines and geometric forms of Art Deco and the emerging International Style. Demand for Tiffany's elaborate and costly creations declined. The Great Depression further impacted the market for luxury goods.

Tiffany himself became less involved in the day-to-day operations of the studios in his later years. The company faced financial difficulties and declared bankruptcy in 1932. Louis Comfort Tiffany died shortly thereafter, on January 17, 1933, in New York City. At the time of his death, his style was considered somewhat passé by the proponents of modernism.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Despite the decline in popularity during his later years and the decades immediately following his death, Louis Comfort Tiffany's reputation underwent a major revival starting in the mid-20th century. Scholars and collectors rediscovered the extraordinary beauty and technical innovation of his work. His lamps, windows, and glass vessels, once relegated to dusty attics, began to command high prices at auction and find prominent places in museum collections.

Today, Louis Comfort Tiffany is celebrated as a pivotal figure in American art and design. His pioneering work in glass pushed the medium's boundaries, creating unparalleled effects of color and light. His lamps and windows remain iconic examples of Art Nouveau design, admired for their intricate craftsmanship and naturalistic beauty. His concept of the unified interior and his embrace of diverse media solidified his role as a leader in the American Arts and Crafts and Aesthetic movements.

His legacy is preserved and promoted by institutions like the Charles Hosmer Morse Museum of American Art, which holds the world's most comprehensive collection of his work, including the reconstructed chapel interior from the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition and salvaged elements from Laureltown Hall. The Neustadt Collection of Tiffany Glass in New York City also houses an exceptional collection, particularly focused on lamps and archival flat glass. Louis Comfort Tiffany's vision continues to inspire artists and designers, and his luminous creations remain a testament to his mastery of light, color, and form, securing his place as one of America's most original and influential artists.