Anna de Weert (1867-1950) stands as a significant, albeit sometimes underappreciated, figure in the landscape of Belgian art at the turn of the 20th century. A dedicated practitioner of Impressionism, with a particular affinity for the nuanced play of light characteristic of Luminism, de Weert carved out a distinct artistic identity. Her life and work offer a fascinating glimpse into the vibrant artistic milieu of Ghent and Brussels, the challenges and opportunities for female artists of her era, and the enduring allure of capturing the ephemeral beauty of nature on canvas. This exploration will delve into her origins, artistic development, signature style, key works, and her position within the broader context of her contemporaries.

Early Life and Artistic Nurturing

Anna Cogen was born in Ghent, Belgium, in 1867, into a family deeply embedded in the artistic and literary culture of the region. This environment was not merely supportive but actively formative. Her lineage was rich with creative talent; notably, her uncles, Alphonse Cogen and Felix Cogen, were both established painters. Their presence and practice would undoubtedly have provided early exposure to the world of art-making, offering inspiration and perhaps even informal guidance.

Furthermore, her maternal grandfather was Karel Lodewijk Ledeganck, a respected Flemish poet and writer. This literary connection in her immediate family suggests an atmosphere where intellectual and aesthetic pursuits were highly valued. Growing up surrounded by painters and a legacy of literary achievement likely instilled in young Anna a profound appreciation for the arts in its various forms, fostering an environment where her own artistic inclinations could take root and flourish. The societal norms of the upper class, to which her family belonged, often included an education in the arts for young women, but Anna's engagement seems to have transcended mere polite accomplishment, pointing towards a deeper, more intrinsic passion.

Formal Artistic Education and the Influence of Emile Claus

While her familial environment provided a fertile ground for her artistic sensibilities, Anna de Weert sought formal training to hone her skills. She initially received private instruction from artists in Ghent, a common path for aspiring painters of her time. However, a pivotal moment in her artistic development came in 1893 when she began to study under the tutelage of Emile Claus (1849-1924).

Claus was a towering figure in Belgian art, widely regarded as the leading proponent of Luminism, a variant of Impressionism that emphasized the depiction of intense light and its effects. His studio in Astene, known as "Zonneschijn" (Sunshine), became a magnet for artists eager to learn his techniques for capturing the vibrant, sun-drenched landscapes of the Leie region. De Weert's decision to study with Claus was significant, placing her directly at the heart of this influential movement.

Under Claus, de Weert would have been immersed in the principles of plein air painting, direct observation of nature, and the Impressionist concern with fleeting moments and atmospheric conditions. Claus's own work, characterized by its radiant palette and dynamic brushwork, profoundly influenced his students. Anna de Weert absorbed these lessons, developing a keen sensitivity to the subtleties of light and color. She became particularly adept at capturing specific times of day, often meticulously noting the exact hour of a scene's completion on the reverse of her canvases, a testament to her dedication to capturing transient optical effects.

She was not alone in this pursuit. Claus's circle included other notable artists who would also make their mark, such as Jenny Montigny (1875-1937), who developed a close and long-lasting personal and artistic relationship with Claus, and Yvonne Serruys (1873-1953). Other students and associates in this vibrant artistic environment included Georges Buyse (1864-1916) and Rodolphe De Saegher (1871-1940). This community of artists, learning and working in proximity, fostered an environment of shared exploration within the Luminist and Impressionist idioms.

Marriage and Continued Artistic Pursuit

In 1891, Anna Cogen married Maurice De Weert, a lawyer. Following the convention of the time, she adopted her husband's surname, thereafter being known as Anna de Weert. Importantly, her marriage did not curtail her artistic ambitions. Maurice De Weert appears to have been supportive of her career, and she continued her studies with Emile Claus after her marriage, indicating a serious commitment to her professional development as a painter.

Her home, often situated near the picturesque Leie river, became both a domestic space and an extension of her studio. The landscapes surrounding her, particularly the play of light on the water and through the foliage, became recurrent subjects in her work. This integration of her personal life with her artistic practice was characteristic of many female artists who balanced societal expectations with their creative drives. The ability to paint the immediate environment allowed for a continuous engagement with her primary source of inspiration.

The Impressionist and Luminist Style of Anna de Weert

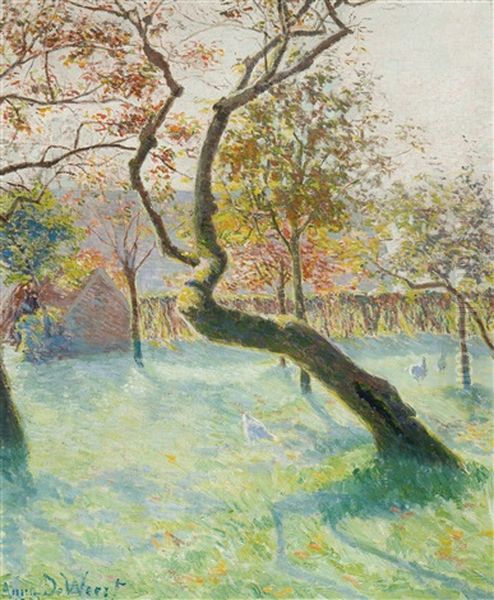

Anna de Weert's artistic style is firmly rooted in Impressionism, with a strong leaning towards the Belgian variant known as Luminism. Her primary concern was the depiction of light and its transformative effect on the landscape. She sought to capture the sensory experience of being in nature, translating the visual phenomena of sunlight, shadow, and reflection into paint.

Her canvases are often characterized by a vibrant palette, though perhaps more nuanced and less overtly dazzling than some of her French Impressionist counterparts. She employed broken brushwork, a hallmark of Impressionism, to convey the shimmer of light and the texture of natural forms. Her compositions often feature gardens, river scenes, and rural landscapes, reflecting her deep connection to the Belgian countryside, particularly the region around the Leie River, which was a favored subject for many Luminist painters.

A distinctive aspect of her practice was her meticulous attention to the specific conditions of light at particular moments. As mentioned, she would often inscribe the date and time of execution on the back of her paintings. This habit underscores her commitment to capturing the fleeting, ephemeral qualities of light, a core tenet of Impressionist theory. It suggests a scientific, observational approach underpinning her romantic and aesthetic appreciation of nature. Her works are not just pretty pictures; they are studies in optics and atmosphere.

Representative Works: Capturing Nature's Essence

Several works stand out as representative of Anna de Weert's style and thematic concerns. While a comprehensive catalogue is extensive, a few key examples illustrate her mastery.

Flowers in the Garden (1912): This painting likely exemplifies her love for garden scenes, a popular subject for Impressionist painters. One can imagine a canvas alive with the vibrant colors of blooming flowers, rendered with loose, energetic brushstrokes that capture the play of sunlight on petals and leaves. Such a work would showcase her ability to translate the sensory richness of a cultivated natural space into a compelling visual experience.

Août dans la plaine (August in the Plain) (1914): The title itself evokes a specific time and place, suggesting a landscape bathed in the strong, warm light of late summer. This work would likely demonstrate her skill in depicting expansive outdoor scenes, capturing the atmospheric haze and the golden hues characteristic of the harvest season. Her focus on the "plain" suggests an interest in the broad vistas and the subtle interplay of light and shadow across open terrain.

Les Pavots (The Poppies) (undated): Poppies, with their brilliant red hue, were a favorite motif for many Impressionists, including Claude Monet. De Weert's rendition would likely focus on the intense color of the flowers set against a contrasting background, perhaps a green field or a sunlit sky. This subject would allow her to explore the expressive potential of pure color and the dynamic forms of the flowers swaying in the breeze.

These works, and many others, demonstrate her consistent engagement with the core principles of Impressionism: the depiction of light, the use of vibrant color, the practice of plein air painting, and a focus on everyday landscapes and natural beauty. Her oeuvre contributes significantly to the Belgian Impressionist tradition.

Exhibitions, Recognition, and Artistic Associations

Anna de Weert was an active participant in the art world of her time, exhibiting her work regularly and engaging with various artistic societies. Her participation in these forums was crucial for gaining recognition and establishing her reputation.

She exhibited her works in Belgium and further afield, including in Southern France, a region also known for its attraction to artists captivated by light. In 1907, she participated in the prestigious Brussels Salon, a key venue for artists to showcase their latest creations. The same year marked a significant milestone in her career when she was invited to exhibit at the Salon d'Automne in Paris. This invitation was a notable honor, placing her work on an international stage alongside prominent French and international artists. The Salon d'Automne was known for its progressive stance, often featuring more avant-garde works than the more traditional Paris Salon.

Further evidence of her international activity includes an exhibition in Zurich in 1908, where she presented five paintings. Locally, she was deeply involved with the "Cercle Artistique et Littéraire" (Artistic and Literary Circle) in Ghent, participating in their exhibitions, such as the one held in 1899. These circles were vital hubs for artists and intellectuals, fostering dialogue and providing platforms for exhibition.

Perhaps one of her most significant contributions to the artistic landscape was her role in the "Vie et Lumière" (Life and Light) artists' association. Co-founded with her mentor Emile Claus and other like-minded artists, this group was dedicated to promoting Luminist painting in Belgium. "Vie et Lumière" organized exhibitions and served as a focal point for artists who shared a common aesthetic vision centered on the depiction of light. Her involvement in such a group underscores her commitment not only to her own practice but also to the broader movement of which she was a part. Other artists associated with or exhibiting alongside "Vie et Lumière" included Modest Huys (1874-1932), known for his Impressionist and later more Expressionist landscapes.

Her exhibition record was substantial. For instance, an exhibition in Brussels in 1900 featured 77 of her works, and another in Ghent in 1903 showcased an impressive 103 pieces. Such large solo or significant group participations indicate a prolific output and a recognized presence in the Belgian art scene.

The Belgian Art Scene: Contemporaries and Connections

Anna de Weert operated within a rich and dynamic artistic environment in Belgium. Beyond her direct mentor Emile Claus and fellow students like Jenny Montigny, Yvonne Serruys, Georges Buyse, and Rodolphe De Saegher, the Belgian art world at the turn of the century was populated by numerous talented individuals exploring various modern art movements.

While direct records of specific collaborations or intense rivalries with all her contemporaries are not extensively detailed in the provided information, artists of this period often moved in overlapping circles, exhibited in the same salons, and were aware of each other's work. The "Vie et Lumière" group itself was a form of collective artistic endeavor.

Modest Huys, for example, was another significant figure in Belgian Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, often depicting scenes of rural life and landscapes of the Leie region. He, like de Weert, exhibited with "Vie et Lumière," indicating a shared platform and aesthetic alignment.

James Ensor (1860-1949), though known for a vastly different, more Symbolist and often grotesque style, was a major contemporary figure in Belgian art. While his artistic concerns diverged significantly from de Weert's Luminist focus, his prominent presence contributed to the overall vibrancy and diversity of the Belgian art scene during her active years.

Albert Lemmet (active late 19th - early 20th century) was another Belgian painter active during this period, part of the broader artistic community. The Cogen uncles, Alphonse (1822-1907) and Felix (1838-1907), though of an earlier generation, provided a familial link to the established art world and represented more traditional approaches from which Impressionism diverged.

The art scene was a complex web of influences, shared exhibition spaces, and artistic societies. Artists like Anna de Weert contributed to this fabric through their individual work, their participation in groups like "Vie et Lumière," and their presence in major salons. While the provided information doesn't detail specific competitive dynamics, the art world is inherently a space where artists seek recognition, and a degree of professional competition is natural, even among those who share aesthetic goals. However, the emphasis in groups like "Vie et Lumière" was often on mutual support and the promotion of a shared artistic vision.

Later Life and Enduring Legacy

The death of her husband, Maurice De Weert, in 1930 marked a significant turning point in Anna's personal life. Following this loss, she reportedly reduced her public appearances and focused more on her private life. However, this did not mean an end to her artistic endeavors. She continued to paint, and her works from the post-1930 period, including those created after World War II, are said to still reflect her profound understanding of nature and light.

Anna de Weert passed away in 1950, leaving behind a substantial body of work. Her paintings are held in various Belgian museums, a testament to her recognized contribution to the nation's artistic heritage. While perhaps not as internationally famous as some of her male French Impressionist counterparts, her role within Belgian Impressionism, and particularly within the Luminist movement, is undeniable.

Her legacy is that of a dedicated and talented artist who skillfully captured the beauty of the Belgian landscape through the lens of Impressionist and Luminist principles. She was a pioneering woman in a field still largely dominated by men, successfully navigating her career, gaining recognition, and contributing to influential artistic associations. Her work serves as an important reminder of the richness and diversity of Impressionism as it manifested outside of France, and specifically of the unique contributions of Belgian artists to this global movement. Her paintings continue to resonate with viewers for their sensitivity to light, their vibrant depiction of nature, and their quiet, enduring beauty. Anna de Weert remains an important figure for those studying Belgian art history and the broader Impressionist movement.