Jenny Montigny (1875-1937) stands as a significant, albeit for a long time overlooked, figure in the landscape of Belgian art at the turn of the 20th century. A dedicated practitioner of Impressionism, and more specifically its Belgian iteration often termed Luminism, Montigny's work is characterized by its sensitive portrayal of light, intimate domestic scenes, and vibrant landscapes. Her life and career offer a compelling narrative of artistic passion, the challenges faced by female artists of her era, and the enduring power of art to transcend periods of neglect. This exploration seeks to illuminate her journey, her artistic contributions, and her rightful place within the annals of art history, alongside the contemporaries who shaped and were shaped by the same artistic currents.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Jeanne (Jenny) Montigny was born in Ghent, Belgium, in 1875, into an affluent and well-regarded family. Her father, Jules Montigny, was a lawyer and university professor of Luxembourgish origin, holding a prominent position as head of the law faculty and later as rector of Ghent University. Her mother, Joanna Helena Mair, hailed from a Dutch-Scottish merchant family. This upper-middle-class, French-speaking milieu provided a comfortable upbringing but also came with certain societal expectations, particularly for a young woman.

Despite the conventional path laid out for women of her social standing, Jenny Montigny developed an early and fervent passion for painting. This artistic inclination, however, was not initially supported by her parents, who envisioned a more traditional future for their daughter. The art world, especially for women aspiring to be professional painters, was not an easy domain to enter, often viewed as unsuitable or merely a genteel hobby rather than a serious vocation.

A pivotal moment in Montigny's artistic awakening occurred in 1892 (some sources suggest 1889 or early 1890s for her first encounter with his work). At an exhibition in Ghent, she encountered the painting The Kingfishers (De ijsvogels) by Emile Claus (1849-1924), a leading figure of Belgian Impressionism. The painting's vibrant depiction of light and nature left an indelible mark on the young Montigny, solidifying her resolve to pursue art under his tutelage. This decision marked a significant turning point, setting her on a path that would define her life, despite familial reservations.

The Mentorship of Emile Claus and Vie et Lumière

Determined to learn from the master who had so inspired her, Jenny Montigny, at the age of nineteen (around 1893, though some sources state as early as 1895 for formal study), sought out Emile Claus. She traveled to his studio, Villa Zonneschijn (Sunshine Villa), in Astene, a picturesque village on the River Lys near Deinze. Claus, initially perhaps surprised by the young woman's determination, accepted her as a private pupil. This was a significant step, as formal art academies often had restrictive policies for female students, and private tutelage with an established artist was a valuable alternative.

The relationship between Montigny and Claus evolved into a profound and lifelong mentorship. She became one of his most devoted and talented students, alongside other notable female artists like Anna De Weert (née Cogen) and Yvonne Serruys. Montigny would spend summers in Astene, immersing herself in the Luminist principles championed by Claus, focusing on capturing the fleeting effects of light and atmosphere in the idyllic landscapes of the Lys region. The bond between mentor and pupil was deep, often described as akin to a father-daughter or even a mother-son like connection, with Claus providing artistic guidance and Montigny offering companionship, especially in his later years.

Emile Claus was a central figure in the Belgian art scene, known for popularizing Impressionism with a distinct local flavor. He was a founding member of the "Vie et Lumière" (Life and Light) society in 1904, an association of Belgian Luminist painters. While Montigny was not a founding member, her artistic practice was deeply aligned with the group's ideals. Vie et Lumière aimed to promote art that celebrated the vibrant effects of sunlight, often through plein-air painting. Other artists associated with or influenced by this movement included Adrien-Joseph Heymans, Georges Lemmen (who also explored Pointillism, akin to Georges Seurat and Paul Signac), and later figures who absorbed Luminist principles into their work. Montigny's association with Claus placed her firmly within this influential circle.

Artistic Style: Luminism, Intimacy, and Nature

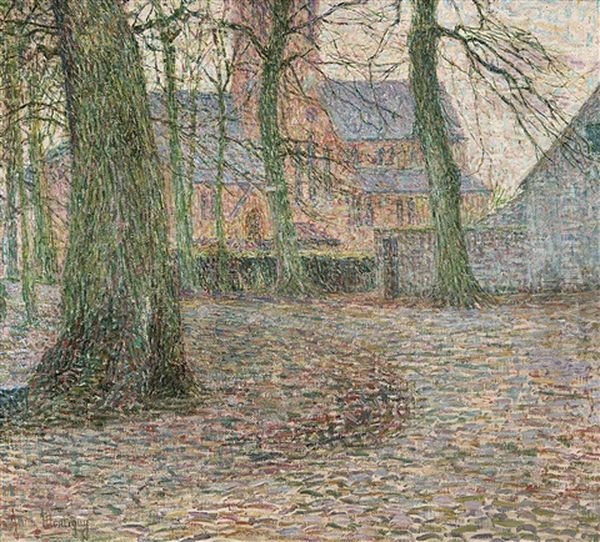

Jenny Montigny's artistic style is best understood as a form of Impressionism with a strong emphasis on the qualities of light, a characteristic of Belgian Luminism. Unlike the more analytical approach of French Impressionists like Claude Monet or Camille Pissarro, Belgian Luminism, while sharing the plein-air practice and broken brushwork, often retained a slightly more solid form and a particular sensitivity to the specific atmospheric conditions of the Flanders region.

Her canvases are typically bathed in a warm, often golden light, capturing the sun-dappled gardens, tranquil riverbanks, and the play of light on figures. She employed a palette of bright, clear colors, applied with lively, visible brushstrokes that convey a sense of immediacy and vibrancy. Her technique involved building up layers of color to create texture and depth, effectively rendering the shimmering effects of light on surfaces, whether it be foliage, water, or human skin.

Thematically, Montigny's oeuvre is rich and varied, though certain subjects recur with notable frequency. She was particularly drawn to depicting children, often shown at play in sunlit gardens or in quiet moments of contemplation. These scenes are imbued with a sense of innocence and tenderness. Works like Jeux d'enfants dans un jardinet fleuri (Children Playing in a Flowery Garden) exemplify this aspect of her work, showcasing her ability to capture the uninhibited joy of childhood within a vibrant natural setting.

Landscapes, especially those around the River Lys and in her own garden, were another favored subject. Orchard in Summer, for instance, reveals her skill in rendering the lushness of nature and the dappled sunlight filtering through trees. She also painted still lifes, such as Nature morte à Deurle (Still Life in Deurle), demonstrating her versatility.

A significant and recurring theme in Montigny's work is motherhood and the intimate bond between mother and child. Paintings often titled or described as Mothership or depicting maternal figures with their offspring highlight her focus on domestic intimacy and the nurturing role of women. These works resonate with the art of other female Impressionists like Berthe Morisot and Mary Cassatt, who also frequently explored themes of womanhood and family life, offering a female perspective within a predominantly male art world. Montigny's depictions are characterized by their warmth, empathy, and a quiet dignity.

Exhibitions, Recognition, and Challenges

Jenny Montigny began to exhibit her work in the early 20th century. She made her debut at the Ghent Salon in 1901 and participated in the Triennial Exhibition in Astene in 1902. Her talent was recognized, and she became a member of the prestigious "Cercle Artistique et Littéraire" in Ghent. She also exhibited regularly in Brussels and Antwerp. Her association with Emile Claus undoubtedly helped open doors, but her own skill ensured her continued presence in the Belgian art scene.

Her reputation extended beyond Belgium. During World War I, like many Belgian artists including Emile Claus himself, Montigny spent time in London. She exhibited her works there, gaining international exposure. This period was crucial for many Belgian artists who found refuge and continued their practice in Britain. Artists like Théo van Rysselberghe, known for his Pointillist works and association with Les XX, also had connections abroad, highlighting the international network of artists at the time.

Despite these successes, Montigny faced challenges. As a female artist, she navigated a field where recognition and financial stability were harder to achieve compared to her male counterparts. The art market was fickle, and tastes began to shift away from Impressionism in the post-war era with the rise of movements like Expressionism, championed in Belgium by artists such as Constant Permeke, Gustave De Smet, and Frits Van den Berghe, who formed the core of the second Latem school.

The death of Emile Claus in 1924 was a profound personal and professional blow to Montigny. She had lost her mentor, confidant, and a crucial supporter. Following his death, and with the waning popularity of Impressionism, Montigny's career gradually faded from public prominence. She continued to paint, but the vibrant art scene that had once celebrated her style was evolving. Economic difficulties also beset her in her later years, reportedly leading to her having to sell her villa.

Later Years, Obscurity, and Rediscovery

The years following Claus's death were marked by increasing isolation for Jenny Montigny. While she remained dedicated to her art, she found herself somewhat adrift in a changing artistic landscape. The vibrant Luminist movement, so central to her development, had lost its primary champion, and new artistic ideologies were gaining traction. The art world, much like society itself, was undergoing rapid transformation in the interwar period.

Montigny continued to live and work in Deurle, a village near Astene that had become an artist's colony, largely due to Claus's presence. However, without the same level of public exposure and critical attention, her work, along with that of some other Luminists, began to recede from the collective memory of the art establishment. She passed away in Deurle in 1937 from cancer, relatively unknown to the broader public at the time of her death, her contributions largely overshadowed and forgotten. For several decades, her name was primarily mentioned only in connection with Emile Claus, as one of his pupils.

The rediscovery of Jenny Montigny's work began in the latter part of the 20th century. A significant retrospective exhibition was held in Deurle in 1987, which brought her art back into the public eye. This was followed by another important exhibition at the Museum van Deinze en de Leiestreek (Museum of Deinze and the Lys Region) in Deinze. These exhibitions were crucial in re-evaluating her oeuvre and recognizing her individual artistic merit.

A major milestone in her posthumous recognition was the large retrospective dedicated to her at the Musée Camille Pissarro in Pontoise, France, in 1995. This exhibition, significantly, placed her within the broader context of Impressionism, acknowledging her as a distinct voice. Art historians, such as Mieke Ackx, began to champion her work, arguing for its intrinsic qualities and importance beyond her association with Claus. These efforts have helped to restore Jenny Montigny to her rightful place as a significant Belgian Impressionist painter. Her works are now found in various museums, including the Museum of Fine Arts in Ghent (MSK Gent) and the Museum van Deinze en de Leiestreek, as well as in private collections.

Montigny in the Context of Her Contemporaries

To fully appreciate Jenny Montigny's contribution, it's essential to view her within the rich tapestry of her artistic contemporaries. Her primary mentor, Emile Claus, was a towering figure who bridged late 19th-century Realism with Impressionism, becoming the foremost proponent of Luminism in Belgium. His influence on Montigny was profound, particularly in her approach to light and plein-air painting.

Among her fellow students of Claus, Anna De Weert and Yvonne Serruys also carved out notable careers. De Weert, like Montigny, focused on landscapes of the Lys region, while Serruys later gained recognition as a sculptor. Their shared experience under Claus's guidance created a small but significant cohort of female artists associated with the Luminist movement.

Beyond Claus's immediate circle, the Belgian art scene was vibrant and diverse. The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw the flourishing of groups like "Les XX" (The Twenty) and its successor "La Libre Esthétique," which were instrumental in introducing international avant-garde movements to Belgium. Artists like James Ensor, with his unique and often unsettling Symbolist and proto-Expressionist works, and Théo van Rysselberghe, a key figure in Belgian Neo-Impressionism (Pointillism), were prominent members. While Montigny's style was more aligned with mainstream Impressionism, the progressive atmosphere fostered by these groups undoubtedly contributed to the overall dynamism of Belgian art.

Internationally, Montigny's work can be seen in dialogue with French Impressionists such as Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, and Alfred Sisley, who pioneered the techniques and philosophies of capturing fleeting moments and the effects of light. Her focus on domestic scenes and mother-child relationships also aligns her with female Impressionists like Berthe Morisot and Mary Cassatt. These women, working within a male-dominated art world, often brought a unique sensitivity and perspective to their depictions of everyday life and the female experience. Cassatt, an American working in Paris, was particularly known for her tender portrayals of mothers and children, a theme Montigny also explored with great empathy.

The later decline in Impressionism's popularity coincided with the rise of Post-Impressionist figures like Vincent van Gogh (though his major impact was posthumous) and Paul Cézanne, who pushed art in new directions, and subsequently, the emergence of Fauvism with artists like Henri Matisse, and Cubism with Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. In Belgium itself, Expressionism, particularly the Flemish Expressionism of the Latem schools (with figures like Gustave Van de Woestyne, Constant Permeke, and Gustave De Smet), gained prominence, offering a stark contrast to the light-filled canvases of the Luminists. This shifting artistic landscape contributed to the temporary eclipse of artists like Montigny.

Legacy and Conclusion

Jenny Montigny's artistic journey is a testament to her unwavering dedication to her craft in the face of societal constraints and changing artistic tides. As an artist, she masterfully captured the ephemeral beauty of light and nature, creating works that are both visually captivating and emotionally resonant. Her depictions of gardens, landscapes, children, and maternal figures offer a window into a world imbued with warmth, tranquility, and a profound appreciation for the simple moments of life.

While her close association with Emile Claus was formative and crucial to her development, her posthumous rediscovery has allowed for a more nuanced understanding of her individual talent and contribution. She was not merely a follower but an artist who absorbed the principles of Luminism and applied them with her own distinct sensibility and thematic focus. Her work stands as an important example of Belgian Impressionism and contributes significantly to the representation of female artists within that movement.

The story of Jenny Montigny is also a reminder of the many talented female artists whose contributions have been historically marginalized or overlooked. Her eventual re-emergence from obscurity underscores the importance of ongoing art historical research and curatorial efforts to ensure a more inclusive and comprehensive understanding of art history. Today, Jenny Montigny is recognized as a gifted painter whose luminous canvases continue to enchant viewers, securing her legacy as a cherished figure in Belgian art. Her life and work serve as an inspiration, demonstrating artistic perseverance and the enduring appeal of an art that celebrates light, life, and the quiet beauty of the everyday.