Antoine-Louis Barye stands as a colossus in the realm of nineteenth-century French sculpture, celebrated primarily for his revolutionary work in depicting animals. Born into a period of artistic transition and burgeoning Romanticism, Barye carved a unique niche for himself, elevating animal sculpture, known as the animalier tradition, from mere decorative craft to a powerful form of high art. His life, spanning from 1795 to 1875, witnessed profound changes in French society and art, and his work reflects both the scientific curiosity and the dramatic intensity of his era. He was not just a sculptor but a keen observer, a student of anatomy, and an artist who captured the raw energy, nobility, and often brutal reality of the natural world with unparalleled skill and sensitivity. His legacy endures not only in the magnificent bronzes he created but also in his profound influence on subsequent generations of artists.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Antoine-Louis Barye was born in Paris on September 24, 1795. His origins were relatively humble; his father was initially a carpenter from Lyon who later transitioned to working as a goldsmith in Paris. This familial connection to metalworking provided the young Barye with his first exposure to craftsmanship. He began his training under his father, learning the intricate skills of the goldsmith trade. This early foundation in precision metalwork would prove invaluable throughout his later career as a sculptor, particularly in the finishing of his bronze casts.

To further hone his skills, Barye studied metal engraving under Martin-Guillaume Biennais, a celebrated goldsmith who served Emperor Napoleon I, and also worked with Fourier, another prominent goldsmith associated with the Napoleonic court. This period immersed him in the detailed work required for decorative arts. However, his path took a brief detour when, around 1809 or slightly later, he served in the French army as a topographical engineer, contributing to the mapping efforts during the Napoleonic Wars. This experience, though seemingly unrelated to art, may have sharpened his observational skills and discipline.

Following his military service, Barye fully committed himself to the pursuit of fine art. He gained admission to the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, the epicenter of academic art training in France. There, he studied sculpture under François-Joseph Bosio, a respected Neoclassical sculptor, and painting under the renowned Baron Antoine-Jean Gros, a pupil of Jacques-Louis David known for his large-scale historical paintings often featuring dramatic action and horses. Despite studying under masters rooted in the Neoclassical tradition, Barye's own artistic inclinations would soon lead him towards the burgeoning Romantic movement. He remained at the École des Beaux-Arts until approximately 1823, absorbing the technical rigors of academic training while developing his unique artistic vision.

The Rise of the Animalier

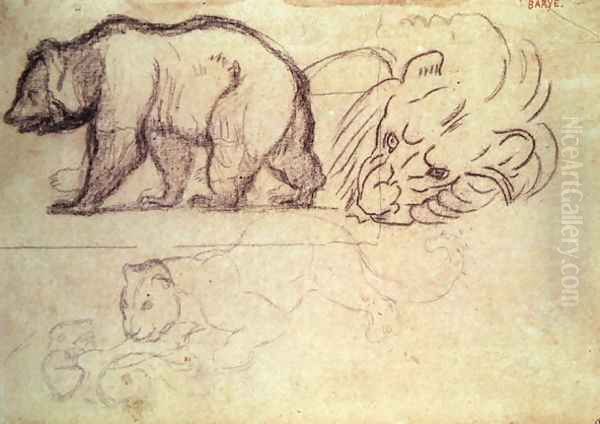

Even during his formal studies, Barye's true passion began to emerge: the depiction of animals. He became a frequent visitor to the Jardin des Plantes in Paris, which housed not only botanical gardens but also a menagerie (zoo) and the Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle (National Museum of Natural History). This institution became his open-air studio and laboratory. He spent countless hours sketching animals from life, observing their movements, postures, and behaviors with meticulous attention. His dedication went beyond surface observation; Barye actively studied animal anatomy, attending dissections conducted at the museum. This scientific approach provided him with an intimate understanding of musculature, skeletal structure, and the mechanics of animal motion, forming the bedrock of his realistic yet dynamic style.

It was during these formative years of intense study at the Jardin des Plantes that Barye forged a significant friendship with the painter Eugène Delacroix, who would become a leading figure of French Romanticism. Delacroix shared Barye's fascination with animals, particularly large felines, and the two artists often sketched side-by-side at the menagerie. They exchanged ideas and drawings, finding mutual inspiration in their shared passion for capturing the wild energy and exoticism of their subjects. This close association undoubtedly reinforced Barye's Romantic sensibilities, encouraging his departure from purely Neoclassical ideals.

Barye's focus on animal subjects placed him at the forefront of what became known as the animalier school. While depictions of animals had long existed in art, they were often secondary elements or treated in a stylized manner. Barye, along with a few contemporaries, sought to elevate animal sculpture to an independent genre, imbuing it with the same seriousness, emotional depth, and artistic ambition traditionally reserved for historical or mythological subjects. His work was also likely influenced by the dramatic animal paintings of Théodore Géricault, another key figure of early Romanticism, known for his powerful portrayals of horses and scenes of intense struggle.

Barye's public breakthrough came at the Paris Salon of 1831. The Salon was the official, highly influential art exhibition sponsored by the Académie des Beaux-Arts. He submitted Tiger Devouring a Gavial of the Ganges (Tigre dévorant un gavial du Gange). This sculpture, depicting a fierce struggle between a tiger and a long-snouted crocodilian native to India, caused a sensation. Its raw energy, anatomical accuracy, and exotic subject matter captivated audiences and critics alike, announcing the arrival of a major new talent. The work was praised for its naturalism and dramatic power, clearly aligning Barye with the Romantic movement's interest in intense emotion and the sublime forces of nature.

Building on this success, Barye achieved even greater acclaim at the Salon of 1833 with his masterpiece, Lion Crushing a Serpent (Lion au serpent). This powerful bronze group depicts a majestic lion pinning a writhing serpent beneath its paw. Commissioned by the French state under King Louis-Philippe, the sculpture was widely interpreted as an allegory of the July Monarchy (represented by the lion) triumphing over disorder and sedition (the serpent). Beyond its political symbolism, the work was lauded for its masterful composition, the realistic rendering of the lion's musculature and fur, the intense focus in its eyes, and the palpable tension of the life-and-death struggle. It cemented Barye's reputation as the preeminent animal sculptor of his time and remains one of his most iconic works, eventually finding a prominent place in the Tuileries Garden and later represented within the Louvre Museum.

Artistic Style and Themes

Antoine-Louis Barye's artistic style is fundamentally rooted in Romanticism, yet it is tempered by a rigorous, almost scientific, naturalism derived from his intense anatomical studies. His work embodies the Romantic fascination with the power, beauty, and untamed spirit of nature, often focusing on moments of high drama, struggle, and primal instinct. He moved away from the idealized forms of Neoclassicism to embrace a more realistic and emotionally charged representation of the animal kingdom.

A hallmark of Barye's style is his exceptional ability to capture animals in motion. Whether depicting a predator stalking its prey, animals locked in combat, or simply a creature in mid-stride, his sculptures possess a remarkable sense of dynamism and arrested energy. This was achieved through his profound understanding of anatomy, allowing him to render musculature tensed for action or relaxed in repose with convincing accuracy. He didn't just sculpt the form of an animal; he sculpted its potential for movement, its inherent vitality.

His choice of subject matter often emphasized the dramatic aspects of animal life – the hunt, the fight for survival, the raw power of predators. Works like Tiger Devouring a Gavial, Jaguar Devouring a Hare, and Lion Devouring a Boar exemplify this focus on the often-violent realities of the natural world. These scenes were not merely sensationalist; they tapped into the Romantic era's interest in the sublime, the awe-inspiring and sometimes terrifying forces that govern nature, far removed from the civilized constraints of human society. There's an inherent tension and emotional intensity in these works that compels the viewer's attention.

Bronze was Barye's preferred medium, and he became a master of bronze casting techniques. He often worked with renowned foundries, such as that of Honoré Gonon and his sons, who cast the monumental Lion Crushing a Serpent. Later, Barye established his own foundry to maintain greater control over the production and quality of his casts. He paid meticulous attention to the surface texture and patina of his bronzes, using chasing (chiseling and refining the metal surface after casting) and chemical treatments to enhance the realism of fur, feathers, or hide, and to create subtle variations in color and reflectivity that brought the sculptures to life. The play of light and shadow across the complex surfaces of his works was a key element of their dramatic effect.

While best known for his dramatic predator scenes, Barye's oeuvre also included quieter, more contemplative depictions of animals, such as his studies of deer, antelope, pheasants, and hares. Works like Seated Hare demonstrate his ability to capture the gentle alertness and delicate form of smaller creatures with equal sensitivity and precision. He also sculpted horses, often with riders, including historical and mythological figures like his Charles VII Victorious or the dynamic Mounted Arab Warrior Killing a Boar. Furthermore, a subtle influence of Orientalism, the 19th-century European fascination with the cultures of North Africa and the Middle East, can sometimes be detected in his choice of exotic subjects (like North African lions or scenes involving Arab figures) and the intense, almost decorative detail in some works.

Key Works and Masterpieces

Antoine-Louis Barye's prolific career yielded numerous sculptures that are now considered masterpieces of the animalier genre and landmarks of 19th-century art. Several works stand out for their artistic innovation, technical brilliance, and lasting impact.

Tiger Devouring a Gavial of the Ganges (1831): This was the work that launched Barye's career at the Salon. Its depiction of a violent encounter between exotic animals from faraway India perfectly captured the Romantic taste for drama and the unfamiliar. The anatomical detail of both the powerful feline and the struggling reptile, combined with the dynamic composition, set a new standard for animal sculpture. It demonstrated Barye's ability to blend scientific observation with intense emotional expression.

Lion Crushing a Serpent (1832-1833): Arguably Barye's most famous work, this monumental bronze became an icon of the July Monarchy and a testament to his skill. The regal power of the lion, its muscles taut, its gaze fixed, contrasted with the desperate writhing of the serpent, creates a compelling narrative of dominance and control. The intricate surface treatment, capturing the texture of the lion's mane and the scales of the snake, showcases Barye's mastery of bronze. Its placement in public spaces like the Tuileries Garden ensured its wide visibility and influence. Versions and studies of this work are found in major collections, including the Louvre and the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C.

Jaguar Devouring a Hare (c. 1850): This sculpture revisits the theme of predator and prey with chilling intensity. The powerful jaguar pins the limp hare, its focus absolute. Barye masterfully conveys the muscular tension in the jaguar's body and the tragic vulnerability of its victim. The work exemplifies his unflinching portrayal of the natural cycle of life and death, rendered with exquisite anatomical detail and compositional force. It is a prime example of his smaller, highly sought-after bronzes.

Walking Lion and Walking Tiger: Barye created several variations of large felines in motion, capturing their characteristic gaits with uncanny realism. These sculptures, often produced in different sizes, showcase his deep understanding of animal locomotion. The subtle shifts in weight, the articulation of joints, and the sense of contained power make these seemingly simple depictions incredibly lifelike and compelling. The Walking Tiger in the Walters Art Museum is a fine example.

Lion of the July Column (c. 1839): While primarily known for his freestanding sculptures, Barye also undertook architectural commissions. He designed a monumental lion relief intended for the base of the July Column on the Place de la Bastille in Paris. Though perhaps less famous than his freestanding works, it demonstrates his ability to adapt his style to large-scale architectural decoration, creating a symbol of strength and vigilance.

Theseus Slaying the Minotaur (various versions, e.g., c. 1843): Although renowned as an animalier, Barye also tackled mythological and human subjects. This group, depicting the Greek hero battling the half-man, half-bull creature, allowed him to explore human anatomy and classical themes while still incorporating his expertise in powerful, dynamic forms and intense struggle. It shows the breadth of his ambition beyond purely animal subjects.

Eagle and Snake: This theme, explored in works found in collections like the Baltimore Museum of Art, presents another classic conflict from the natural world. Barye captures the sharp-eyed focus of the eagle and the desperate defense of the snake, creating a dynamic vertical composition full of tension and energy, showcasing his skill in depicting avian anatomy and movement.

Seated Hare and Standing Hare (various dates, e.g., c. 1850): These smaller works demonstrate Barye's versatility. In contrast to the violent struggles, these sculptures capture the quiet alertness and delicate forms of prey animals. The meticulous rendering of fur texture and the sensitive portrayal of the animal's posture reveal Barye's keen observation extending to less dramatic subjects.

These examples represent only a fraction of Barye's extensive output, which included numerous other depictions of lions, tigers, panthers, bears, deer, antelope, birds, and reptiles, as well as equestrian groups and decorative objects. Each piece, regardless of size or subject, typically bears the hallmarks of his style: anatomical accuracy, dynamic energy, and a profound connection to the spirit of the wild.

Challenges, Business, and Recognition

Despite the critical acclaim that greeted works like Tiger Devouring a Gavial and Lion Crushing a Serpent, Antoine-Louis Barye's career was not without its difficulties. The very novelty and realism of his animal sculptures sometimes met with resistance from the conservative elements within the French art establishment, particularly the jury of the Paris Salon. His focus on animal subjects, often depicted in violent struggle, was considered by some to be less noble or important than traditional historical, mythological, or religious themes. There were periods when his submissions to the Salon were rejected, leading to frustration and financial strain.

Partly in response to these challenges and seeking greater artistic and financial independence, Barye took the entrepreneurial step of establishing his own foundry around 1838, partnering initially with a man named Martin. This allowed him to oversee the casting and finishing of his sculptures directly, ensuring quality control. More significantly, it enabled him to produce and sell smaller bronze editions of his popular works directly to the public. This move was innovative for its time. While large-scale commissions were prestigious, the market for smaller bronzes catered to the growing bourgeois collectors who desired art for their homes.

These editions, meticulously crafted and often offered in various sizes, helped to disseminate Barye's work more widely and build his reputation beyond the confines of the official Salon system. Although this business venture did not always bring immense financial fortune – Barye faced periods of significant debt and even bankruptcy – it played a crucial role in popularizing animalier sculpture and making high-quality art more accessible to a middle-class audience. His bronzes became highly sought after by collectors in France, Britain, and the United States.

Over time, official recognition did come. Barye received numerous honors, including being made a Knight of the Legion of Honour in 1833, and later promoted to Officer (1855) and Commander (1867). His persistence and undeniable talent eventually overcame earlier resistance. In 1854, a significant appointment acknowledged his unique expertise: he became Professor of Zoological Drawing at the Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle, the very institution where he had spent countless hours studying. This position allowed him to formally teach animal anatomy and drawing, passing on his knowledge to a new generation.

The culmination of his official recognition arrived in 1868 when he was elected as a member of the prestigious Académie des Beaux-Arts, the institution whose Salon juries had sometimes rejected him earlier in his career. This election solidified his status as one of France's leading artists. By the time of his death in Paris on June 25, 1875, Antoine-Louis Barye had transformed the field of animal sculpture and achieved lasting renown as a master of his craft.

Influence and Legacy

Antoine-Louis Barye's impact on the art world was profound and multifaceted, extending far beyond his own lifetime. He is widely regarded as the most important figure in the French animalier school, effectively defining the genre in the 19th century and elevating it to unprecedented artistic heights. His work set a benchmark for anatomical accuracy, dynamic composition, and emotional intensity in the depiction of animals that influenced countless other artists.

His immediate successors in the animalier tradition, such as Pierre-Jules Mêne, known for his detailed domestic animals and hunting scenes, Emmanuel Frémiet, famous for his large public monuments including animals, Auguste Cain, and the siblings Rosa Bonheur (primarily a painter but also a sculptor) and Isidore Bonheur, all owed a debt to Barye's pioneering efforts. He demonstrated that animal subjects were worthy of serious artistic treatment and capable of conveying powerful emotions and ideas. His influence spread beyond France, impacting sculptors in Britain, Belgium, and particularly the United States, where his bronzes were avidly collected and admired.

Barye's influence extended to artists outside the specific animalier circle. His close relationship with Eugène Delacroix was one of mutual inspiration, with both artists exploring themes of exoticism, power, and struggle through their respective media. The dramatic intensity of Barye's work resonated with the broader Romantic movement. Perhaps his most famous pupil was Auguste Rodin, who briefly studied with Barye around 1864. Although Rodin's primary focus would become the human figure, the emphasis on anatomical structure, musculature, and expressive modeling that he likely absorbed from Barye remained evident throughout his revolutionary career. Rodin himself acknowledged Barye's importance.

Even artists of later generations found inspiration in Barye's work. Notably, Henri Matisse, a leader of Fauvism and one of the giants of 20th-century modern art, studied and copied Barye's sculptures early in his career, particularly Jaguar Devouring a Hare, as part of his self-education in form and structure. This demonstrates the enduring power and relevance of Barye's modeling even for artists moving towards abstraction. Other artists like the painter and decorator Paul Émile Baudry also acknowledged his influence.

Beyond artistic style, Barye's entrepreneurial approach to producing and marketing bronze editions had a lasting impact. It helped establish a viable market for smaller sculptures suitable for domestic interiors, contributing to the democratization of art collecting in the 19th century. His technical mastery of bronze casting also set high standards for the medium.

Today, Antoine-Louis Barye's sculptures are treasured holdings in major museums across the globe. The Louvre and Musée d'Orsay in Paris, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., the Walters Art Museum and Baltimore Museum of Art in Baltimore, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Caen, and numerous other public and private collections proudly display his work. His sculptures continue to captivate viewers with their blend of scientific precision, Romantic drama, and timeless portrayal of the animal world.

Conclusion

Antoine-Louis Barye remains an essential figure in the history of 19th-century sculpture. Emerging from a background in craftsmanship, he harnessed his technical skills, his passion for the natural world, and the spirit of Romanticism to revolutionize the depiction of animals in art. Through tireless observation at the Jardin des Plantes and rigorous study of anatomy, he achieved an unparalleled realism, capturing not just the physical form of animals but also their energy, movement, and inner life. His dramatic portrayals of struggle and survival resonated deeply with the sensibilities of his era, while his quieter studies revealed a profound sensitivity to the nuances of animal behavior.

As the leading figure of the animalier school, Barye elevated the genre, demanding for it the same respect accorded to more traditional forms of sculpture. His influence extended to contemporaries like Delacroix, pupils like Rodin, and even modern masters like Matisse. His innovative use of bronze editions helped broaden the audience for sculpture. Despite facing challenges and occasional rejection from the art establishment, his genius was ultimately recognized through prestigious appointments and honors. Barye's legacy endures in his powerful and evocative sculptures, which continue to be admired in museums worldwide, testament to his unique ability to fuse scientific accuracy with profound artistic expression, forever changing the way we see animals in art.