The name John Quincy Adams resonates powerfully within American history, primarily associated with the sixth President of the United States (1767-1848), a distinguished diplomat and legislator. However, in the realm of American art, another significant figure bears this distinguished name: John Quincy Adams Ward (1830-1910), a sculptor whose work profoundly shaped the visual landscape and artistic identity of the nation during the latter half of the 19th century. While inquiries sometimes arise regarding a painter named John Quincy Adams with the specific dates 1874-1933, comprehensive historical records and art historical databases do not currently confirm the existence or significant artistic output of such an individual. There are fleeting mentions of a painter named John Quincy Adams with unknown specifics, but the artist who left an indelible mark is unequivocally the sculptor, Ward. This exploration delves into the life, work, and enduring legacy of John Quincy Adams Ward, a pivotal artist often hailed as the "Dean of American Sculptors."

Early Life and Formative Influences

John Quincy Adams Ward was born on June 29, 1830, in Urbana, Ohio. His upbringing on a farm in what was then considered the western frontier of the United States imbued him with a deep appreciation for the natural world and the rugged individualism that characterized American life. This early environment would later manifest in the robust naturalism and distinctly American themes of his sculptures. Unlike many of his contemporaries who sought artistic training in Europe, Ward's formative experiences were rooted in American soil.

His family, with colonial ancestry, provided a backdrop of American heritage. While not initially destined for an artistic career, a period of ill health led him to spend time on his sister's farm in Kentucky. It was during this time that his latent artistic talents, particularly in modeling clay, began to emerge. This burgeoning interest eventually led him to seek formal training.

In 1849, at the age of nineteen, Ward made a pivotal move to Brooklyn, New York, to study under the established sculptor Henry Kirke Brown (1814-1886). Brown was a significant figure in American sculpture, known for his own commitment to American subjects and for fostering a native school of sculpture. This apprenticeship, which lasted for seven years until 1856, was crucial for Ward's development. Under Brown's tutelage, Ward gained comprehensive technical skills in modeling, casting, and carving. He was not merely a student but an active assistant, contributing significantly to major commissions undertaken by Brown's studio.

The Making of an American Sculptor

One of the most notable projects Ward was involved in during his time with Brown was the monumental equestrian statue of George Washington, destined for Union Square in New York City. This commission, completed between 1853 and 1856, provided Ward with invaluable experience in creating large-scale public art. His involvement in such a prominent national monument undoubtedly solidified his ambition and honed his skills. Brown's studio was a hub of activity, and working alongside a master like Brown, who himself had studied in Italy but returned with a desire to create distinctly American art, was profoundly influential. Brown encouraged a direct observation of nature and a departure from the prevailing Neoclassical ideals that often looked to classical antiquity for inspiration.

After completing his apprenticeship, Ward worked independently in Washington, D.C., from 1857 to 1860, creating portrait busts of prominent public figures. This period allowed him to establish his reputation and refine his approach to portraiture, emphasizing character and realism over idealized forms. His time in the nation's capital also exposed him to the political and social currents of the era, further informing his understanding of American identity.

In 1861, a year that marked the beginning of the Civil War, Ward established his own studio in New York City. This move signaled his arrival as an independent and ambitious sculptor ready to make his mark. New York was rapidly becoming the artistic and cultural center of the United States, offering numerous opportunities for commissions and a vibrant community of artists.

The Rise of Naturalism and American Themes

John Quincy Adams Ward's artistic philosophy was characterized by a strong commitment to naturalism and a fervent belief in the importance of American subjects. He advocated for an American school of sculpture, trained in America and focused on American narratives, rather than relying on European academies and classical tropes. His style was direct, often rugged, and imbued with a sense of inherent strength and vitality. He sought to capture the essence of his subjects, whether they were historical figures, allegorical representations, or everyday people, with an unvarnished honesty.

This approach contrasted with the more idealized and often sentimental style of some of his predecessors and contemporaries who were heavily influenced by Neoclassicism, such as Hiram Powers (1805-1873), known for The Greek Slave, or Thomas Crawford (1814-1857), whose Statue of Freedom crowns the U.S. Capitol dome. While these artists made significant contributions, Ward represented a shift towards a more robust and distinctly American realism.

His dedication to American themes was not merely patriotic; it was a belief that the stories, struggles, and triumphs of the American experience offered rich material for artistic expression. This focus resonated with a nation grappling with its identity, particularly in the aftermath of the Civil War.

Landmark Works: Defining a Career

Ward's career is punctuated by several landmark sculptures that not only cemented his reputation but also became iconic representations of American art.

Perhaps his most famous early work, The Indian Hunter, conceived around 1860 and cast in bronze in 1864, was a groundbreaking piece. First exhibited in plaster at the Paris Exposition of 1867 and later installed in New York's Central Park in 1869, this sculpture depicts a Native American hunter intently stalking prey, accompanied by his dog. The work is celebrated for its dynamic composition, anatomical accuracy, and the palpable tension in the figures.

To achieve this realism, Ward reportedly traveled to the Dakota Territory to observe Native American life firsthand, a testament to his dedication to authenticity. The Indian Hunter was a departure from the often-romanticized or stereotyped depictions of Native Americans prevalent at the time. Instead, Ward presented a figure of strength, focus, and dignity, integrated within the natural world. The sculpture's placement in Central Park, a space designed by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux to be a democratic haven, made it accessible to a wide public and contributed to its popularity. The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York also holds a significant version of this work.

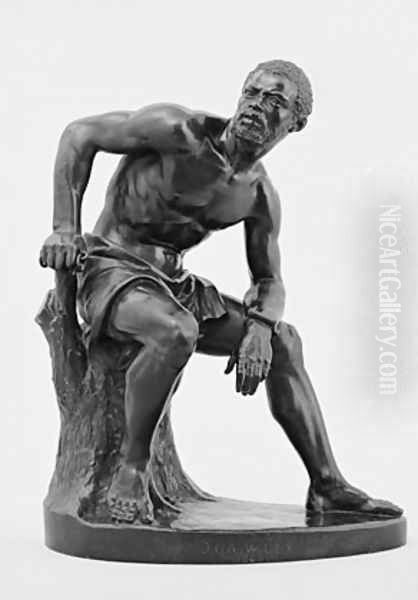

Created in 1863, during the height of the Civil War and shortly after the Emancipation Proclamation, The Freedman is another of Ward's most powerful and historically significant works. This small bronze sculpture depicts a semi-nude African American man, seated on a tree stump, with a broken manacle on his wrist. His gaze is upward, and his body, though muscular, conveys a sense of contemplation and nascent freedom.

The Freedman is a poignant and dignified representation of emancipation. It avoids overt sentimentality, instead focusing on the moment of transition and the complex emotions associated with liberation. The figure's powerful physique suggests resilience, while the broken shackle symbolizes the end of bondage. This work was widely acclaimed for its sensitive portrayal and its timely engagement with one of the most critical issues in American history. The Amon Carter Museum of American Art in Fort Worth, Texas, is among the institutions that hold a cast of this important sculpture. It stands as a testament to Ward's ability to imbue his figures with profound psychological depth.

George Washington Statues

Ward's connection to George Washington, initiated during his apprenticeship, continued throughout his career. Beyond the Union Square equestrian statue he assisted Brown with, Ward created his own standing statue of Washington in 1883, which stands on the steps of Federal Hall National Memorial in New York City, on the approximate site where Washington took the oath of office as the first U.S. President. This imposing bronze figure portrays Washington in a moment of civic leadership, his hand outstretched as if addressing the people. It is a work of sober dignity and commanding presence, reflecting Ward's mature style.

Public Monuments and National Narratives

A significant portion of John Quincy Adams Ward's oeuvre consists of public monuments and portrait statues of prominent Americans. These works played a crucial role in shaping public memory and constructing a visual narrative of the nation's history.

His statue of Horace Greeley (1890), the influential newspaper editor and publisher, originally stood in front of the New York Tribune Building and is now located in City Hall Park, New York. The sculpture captures Greeley's distinctive appearance and intellectual intensity.

The Henry Ward Beecher Monument (1891) in Cadman Plaza, Brooklyn, honors the famed abolitionist preacher. Ward depicted Beecher in a characteristic oratorical pose, surrounded by figures representing his humanitarian concerns, including a Black woman and child, symbolizing his anti-slavery stance.

The James A. Garfield Monument (1887) in Washington, D.C., is a complex memorial to the assassinated president. The central bronze statue of Garfield is surrounded by allegorical figures representing different stages of his life – Student, Warrior, and Statesman – showcasing Ward's skill in both portraiture and allegorical representation.

Other notable public works include the statue of Major General George H. Thomas (1879) in Thomas Circle, Washington, D.C., an equestrian monument praised for its realism and balance, and the statue of Major General Winfield Scott Hancock (1896) on Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, D.C. He also created a statue of Simon Bolivar for Central Park, a gift from Venezuela.

These public commissions underscore Ward's status as a leading national sculptor. His ability to create dignified and compelling representations of historical figures made him a sought-after artist for commemorative projects across the country. His works were not merely likenesses but interpretations that conveyed the character and significance of his subjects within the broader American narrative.

Leadership in the American Art World

John Quincy Adams Ward was not only a prolific artist but also a significant leader and organizer within the American art community. He was deeply committed to advancing the status of American artists and art institutions.

He was a founder of the National Sculpture Society in 1893 and served as its first president from 1893 to 1904 (some sources state until 1905). This organization was established to promote the development of sculpture in the United States, to foster the professional interests of sculptors, and to encourage the use of sculpture in public spaces. His leadership was instrumental in raising the profile of American sculpture both nationally and internationally.

Ward was also actively involved with the National Academy of Design, a prestigious institution founded in 1825 by artists including Samuel F.B. Morse, Thomas Cole, and Asher B. Durand. Ward was elected a full Academician in 1863 and served as its president from 1873 to 1874. His involvement with the Academy further solidified his position as a central figure in the American art establishment.

Furthermore, he was a trustee of the American Academy in Rome, an institution dedicated to providing American artists and scholars with opportunities to study in Rome. His participation in these organizations demonstrates his commitment to fostering artistic talent and creating a supportive infrastructure for American artists. He was also a member of the Architectural League of New York and the National Institute of Arts and Letters.

Artistic Collaborations and Contemporaries

Throughout his career, Ward engaged in collaborations and worked within a vibrant artistic milieu. His early collaboration with Henry Kirke Brown was foundational. Later, he collaborated with the architect Richard Morris Hunt (1827-1895) on several projects, creating sculptural adornments for Hunt's buildings. For instance, Hunt designed the pedestal for Ward's Washington statue at Federal Hall. In 1902, Ward collaborated with sculptor Paul Wayland Bartlett (1865-1925) on the pediment for the New York Stock Exchange Building, titled Integrity Protecting the Works of Man.

Ward's career spanned a period of immense growth and change in American art. He was a contemporary of the later Hudson River School painters like Albert Bierstadt (1830-1902) and Frederic Edwin Church (1826-1900), who, like Ward, sought to capture the grandeur and unique character of the American landscape and experience.

In the realm of sculpture, he was a senior figure to a new generation of American sculptors who often embraced Beaux-Arts aesthetics, many of whom trained in Paris. These included Augustus Saint-Gaudens (1848-1907), renowned for works like the Adams Memorial and the Shaw Memorial, and Daniel Chester French (1850-1931), famous for the Minute Man statue and the seated Abraham Lincoln in the Lincoln Memorial. While Ward's rugged naturalism differed from the more elegant and often allegorical style of Saint-Gaudens and French, he was respected by them and helped pave the way for their success by elevating the status of American sculpture.

The era also saw the rise of prominent American painters like Winslow Homer (1836-1910) and Thomas Eakins (1844-1916), both known for their unflinching realism and focus on American subjects. Homer's depictions of maritime life and Eakins's penetrating portraits and scenes of everyday American activity shared a kindred spirit with Ward's commitment to authentic representation. Other notable painters of the period include Eastman Johnson (1824-1906), known for his genre scenes and portraits, and landscape painter George Inness (1825-1894), whose work evolved from the Hudson River School style to a more Tonalist approach. Later in Ward's career, American expatriate painters like James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834-1903), John Singer Sargent (1856-1925), and Mary Cassatt (1844-1926) gained international acclaim, bringing diverse European influences into American art.

Ward's insistence on American training and themes provided a counterpoint to the increasing European influence, championing a distinctly national artistic voice.

Personal Life and Later Years

John Quincy Adams Ward was reportedly a man of strong character and conviction, traits reflected in the robustness of his art. Information about his personal life is less detailed than that of his public career. He was married twice, first to Anna Bannan, who died in 1899, and then to Rachel Smith, whom he married in 1909, shortly before his own death. He maintained his studio in New York City for many years, a hub of creativity and a testament to his enduring productivity.

He continued to work and receive commissions well into his later years, remaining an active and respected figure in the art world. His dedication to his craft and his advocacy for American art left a lasting impact.

John Quincy Adams Ward passed away on May 1, 1910, in New York City, at the age of 79. He was buried in Oak Dale Cemetery in his hometown of Urbana, Ohio.

The Enduring Legacy of John Quincy Adams Ward

John Quincy Adams Ward's legacy is multifaceted. As a sculptor, he produced a significant body of work that continues to adorn public spaces and grace museum collections, most notably the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Gallery of Art, and numerous city parks and squares. His commitment to naturalism and American themes helped to define a national school of sculpture, moving away from European dependence and fostering a distinctly American artistic identity.

His sculptures, particularly The Indian Hunter and The Freedman, are recognized as masterpieces of 19th-century American art, valued for their artistic merit and their engagement with important historical and social issues. His public monuments have become integral parts of the urban landscape, shaping public memory and commemorating key figures and events in American history.

As a leader in the art community, Ward played a crucial role in professionalizing the field of sculpture in the United States. His efforts in founding and leading organizations like the National Sculpture Society helped to elevate the status of sculptors and promote the integration of sculpture into public life. He was a mentor and an inspiration to younger artists, even as artistic styles evolved.

While the name John Quincy Adams might first evoke the image of a president, the contributions of John Quincy Adams Ward, the sculptor, are equally significant within the annals of American cultural history. He was a foundational figure who truly sculpted an American identity, leaving behind a legacy cast in bronze and etched in the nation's artistic consciousness. His work remains a powerful testament to the vitality and distinct character of American art in the 19th century.