Anton Emanuel Peschka, born in Vienna on February 21, 1885, and passing away in the same city on March 9, 1940, was an Austrian painter whose artistic journey is inextricably linked with the incandescent, albeit tragically short, career of his close friend and brother-in-law, Egon Schiele. While Peschka may not have achieved the same monumental posthumous fame as Schiele, he was a significant participant in the vibrant, revolutionary art scene of early 20th-century Vienna. His work, primarily focused on landscapes, still lifes, and occasionally figures, reflects the era's shift towards Expressionism, imbued with a distinct Austrian flavour.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Imperial Vienna

Vienna at the turn of the century was a crucible of artistic and intellectual ferment. The Austro-Hungarian Empire, though politically declining, was culturally effervescent. This was the Vienna of Sigmund Freud, Gustav Mahler, Arnold Schoenberg, and Ludwig Wittgenstein. In visual arts, the Vienna Secession, founded in 1897 by artists like Gustav Klimt, Koloman Moser, and Carl Moll, had already challenged the entrenched academicism of the Association of Austrian Artists and the Vienna Künstlerhaus. They sought to create a uniquely Austrian modern art, embracing Art Nouveau (Jugendstil) and Symbolism, and opening Vienna to international artistic currents.

It was into this dynamic environment that Anton Peschka entered his formative years. Like many aspiring artists of his generation, he enrolled at the prestigious Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna (Akademie der bildenden Künste Wien). The Academy, however, remained a bastion of conservative, traditional art education, often at odds with the avant-garde stirrings outside its hallowed halls. A key figure representing this academic rigidity was Professor Christian Griepenkerl, a history painter whose teaching methods were considered stifling by more progressive students.

The Academy and the Fateful Friendship with Egon Schiele

At the Academy, Peschka encountered a student who would become one of the most defining figures of Austrian Expressionism and a pivotal person in his own life: Egon Schiele. Schiele, younger than Peschka by five years, was a prodigious talent who also found the Academy's curriculum constricting. Peschka and Schiele, along with other like-minded students, chafed under the conservative tutelage. Their shared dissatisfaction with the academic system and their burgeoning desire for a more personal and expressive form of art forged a strong bond between them.

This period was crucial for Peschka's artistic development. While initially, like many young Viennese artists, he would have been exposed to the decorative opulence of Gustav Klimt, the dominant figure of the Secession, it was Schiele's burgeoning, raw, and psychologically charged style that would prove more directly influential. Schiele himself was moving from a Klimt-influenced decorative phase towards a more linear, angular, and emotionally intense form of expression.

The friendship between Peschka and Schiele was not merely one of shared artistic ideals; it deepened into a familial connection. Peschka would eventually marry Egon Schiele's younger sister, Gertrud "Gerti" Peschka (née Schiele), making him Schiele's brother-in-law. This close personal tie further cemented their artistic and personal camaraderie.

The Neukunstgruppe: A Rebellion and a New Beginning

The simmering discontent with the Academy's conservatism reached a boiling point in 1909. Egon Schiele, famously, was the most vocal in his rebellion. He, Anton Peschka, and several other students, including Anton Faistauer, Franz Wiegele, Robin Christian Andersen, and Albert Paris Gütersloh (who would later become a significant writer and painter), decided to leave the Academy. This act of defiance was a bold statement against the artistic establishment.

Shortly after their departure, Schiele took the lead in founding the Neukunstgruppe (New Art Group). Anton Peschka was a founding member and an active participant. The Neukunstgruppe aimed to provide a platform for young, progressive artists who sought to break free from academic constraints and the perceived aestheticism of the later Secession movement, which some younger artists felt had become too decorative and less challenging. They sought a more direct, unvarnished, and emotionally resonant art. Their first exhibition was held in December 1909 at the Pisko Salon in Vienna.

The Neukunstgruppe, though relatively short-lived, was an important stepping stone for Austrian Expressionism. It provided an alternative to the established art institutions and allowed artists like Peschka and Schiele to exhibit their more radical works. The group's ethos was characterized by a search for individual expression, an interest in the psychological, and often a departure from traditional notions of beauty. Other artists associated with or exhibiting with the Neukunstgruppe at various points included Oskar Kokoschka, another towering figure of Austrian Expressionism, though Kokoschka's relationship with the group was complex and he largely forged his own path.

Peschka's Artistic Style: Color Expressionism and Lyrical Landscapes

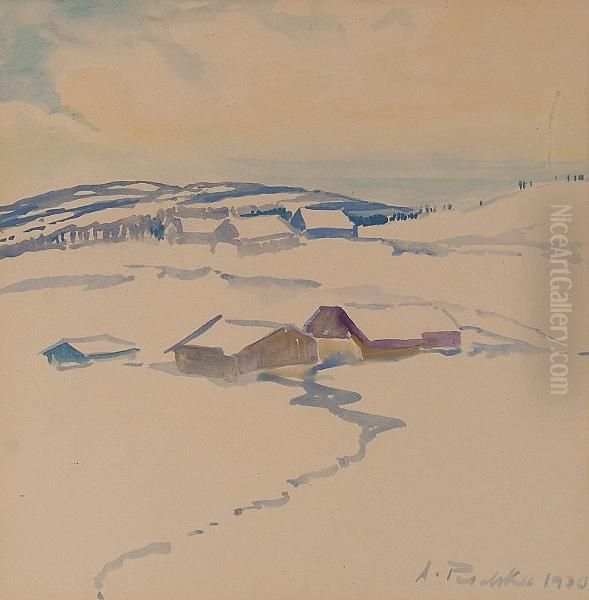

Anton Peschka's artistic style is best characterized as a form of Color Expressionism. While influenced by Schiele's linear intensity and psychological probing, Peschka's work often retained a more lyrical quality, particularly in his landscapes and still lifes. He demonstrated a keen sensitivity to color, using it not merely for descriptive purposes but to convey mood and emotion. His brushwork could be vigorous and expressive, yet often tempered with a decorative sensibility that perhaps echoed the lingering influence of Viennese Jugendstil.

His landscapes, often depicting the Austrian countryside, are imbued with a sense of atmosphere and a vibrant palette. Unlike the often-anguished cityscapes or self-portraits of Schiele, Peschka's landscapes could evoke a more tranquil, though still emotionally charged, connection with nature. He was adept at capturing the changing light and seasons, translating them into dynamic compositions of color and form.

In his still lifes, Peschka particularly excelled. Flowers were a recurrent motif, allowing him to explore rich color harmonies and expressive brushwork. These works often showcase his ability to balance decorative appeal with emotional depth. The forms of flowers and vases might be simplified or slightly distorted to enhance their expressive power, a hallmark of Expressionist tendencies.

Representative Works and Their Significance

While a comprehensive catalogue raisonné of Peschka's work is not as widely accessible as that of Schiele, several pieces and descriptions provide insight into his oeuvre.

One of his notable works mentioned is _Blumenstilleben_ (Flower Still Life) from 1919. This oil painting, measuring 54.6 cm x 43.2 cm, is described as being in a color expressionist style. Created a year after Schiele's death, it likely reflects Peschka's mature style, where his command of color and expressive form would have been fully developed. In such a work, one might expect to see vibrant, non-naturalistic colors, dynamic brushstrokes, and a composition that emphasizes the emotional impact of the subject rather than a purely objective representation. The choice of flowers, a traditional subject, is reinterpreted through an Expressionist lens, imbuing it with vitality and subjective feeling.

Another work titled _Nackte Frau von hinten sitzend_ (Nude Woman Sitting, Seen from Behind) is listed, though without a date or further details, it's harder to analyze specifically. However, the subject of the nude was central to Schiele and many Expressionists, often used to explore themes of vulnerability, sexuality, and the human condition. If Peschka tackled similar themes, his approach might have differed from Schiele's often raw and confrontational nudes, perhaps imbuing them with his characteristic lyricism or focusing more on formal and coloristic aspects.

It's also important to consider works by Schiele that feature Peschka or his family, as they provide contemporary visual records and highlight their close relationship. Schiele's _Portrait of the Painter Anton Peschka_ (1909) is a significant early work. Created around the time of their departure from the Academy and the formation of the Neukunstgruppe, this portrait likely captures Peschka with the intensity and psychological insight characteristic of Schiele's portraiture. Schiele's portraits were not mere likenesses; they were profound explorations of the sitter's inner state, often conveyed through contorted lines, expressive hands, and piercing gazes. This portrait is a testament to their friendship and shared artistic ambitions during a formative period.

Furthermore, Schiele's painting _Mother with Two Children (Adele Harms and her nephews Wilhelm and Hans)_ (1917), sometimes also linked to depictions of his own wife Edith and a hoped-for child, or even more directly, as mentioned in the provided information, featuring Peschka's son, "Little Anton," as a model for one of the children. If Peschka's son indeed served as a model, it underscores the deep familial bonds and the intermingling of their personal and artistic lives. Schiele's late works, including his depictions of mothers and children, show a softening of his style and a new tenderness, perhaps influenced by his own marriage and the anticipation of fatherhood before his untimely death.

The Enduring Bond: Peschka and Schiele

The relationship between Anton Peschka and Egon Schiele was multifaceted. They were fellow students, artistic rebels, co-founders of an art group, friends, and brothers-in-law. Their artistic paths, while distinct, were deeply intertwined. Peschka was a supportive friend and colleague to the often-volatile Schiele.

Their shared experiences included artistic excursions. The trip to Krumau (Český Krumlov in the present-day Czech Republic), Schiele's mother's hometown, in 1910, was particularly significant for Schiele, providing him with rich subject matter and a temporary escape from Vienna. Peschka's presence on such trips would have offered companionship and an opportunity for shared artistic exploration. Krumau's medieval architecture and winding streets deeply inspired Schiele, leading to some of his most iconic townscapes.

Peschka was also privy to Schiele's thoughts on art and other artists. The mention of Schiele relaying Gustav Klimt's working habits to Peschka in a letter highlights their ongoing dialogue about artistic practice. Klimt, despite being from an older generation, remained a figure of immense importance, and young artists like Schiele and Peschka would have been keen to understand his methods and artistic philosophy.

The tragic death of Egon Schiele from the Spanish flu pandemic in October 1918, just days after his pregnant wife Edith also succumbed, must have been a devastating blow to Peschka, both personally and professionally. Schiele was on the cusp of major international recognition, and his loss was a profound tragedy for Austrian art. For Peschka, it meant the loss of a close friend, a family member, and a towering artistic presence who had significantly shaped his own development.

Peschka's Continued Career and Place in Austrian Art

After Schiele's death, Anton Peschka continued to live and work in Vienna. He outlived his friend by over two decades, passing away in 1940, a period that saw Austria undergo immense political upheavals, including the Anschluss with Nazi Germany in 1938. The artistic climate would have changed dramatically, with modern art, particularly Expressionism, being suppressed and denigrated as "degenerate art" (Entartete Kunst) by the Nazi regime. This hostile environment would have posed significant challenges for artists like Peschka who were associated with modernist movements.

Despite these challenges, Peschka continued to paint, focusing on his preferred subjects of landscapes and still lifes. His works continued to be exhibited, and he maintained a presence in the Austrian art scene. He is noted for his contributions to color expressionism and his works frequently appeared in exhibitions. His dedication to his art, even in the shadow of his more famous brother-in-law and amidst turbulent historical times, speaks to his commitment as a painter.

Historically, Anton Peschka is often viewed in relation to Egon Schiele. While this connection is undeniable and crucial to understanding his career, Peschka was also an artist with his own distinct voice. He absorbed influences from the Viennese milieu, including Klimt and the broader Jugendstil movement, but forged his primary path within the framework of Austrian Expressionism, guided and inspired by Schiele, yet developing a more lyrical and color-focused interpretation.

His involvement with the Neukunstgruppe places him firmly within the narrative of early Austrian modernism. The group, though ephemeral, represented a crucial break from academic tradition and helped pave the way for the broader acceptance of Expressionist art in Austria. Peschka's role as a founding member underscores his commitment to these new artistic ideals.

Other artists from this vibrant Viennese period whose paths might have crossed or whose work provides context include Richard Gerstl, another pioneering Austrian Expressionist whose life also ended tragically and early; Max Oppenheimer (MOPP), a friend of Schiele and an expressive portraitist; and members of the Vienna Secession and Wiener Werkstätte like Josef Hoffmann and the previously mentioned Koloman Moser, whose design aesthetics permeated Viennese culture. Later Austrian Expressionists like Herbert Boeckl or Carry Hauser (who was also part of the Neukunstgruppe circle) continued to develop these artistic currents.

Anecdotes and Unveiling a Deeper Connection

The information regarding unpublished interviews with Peschka and Schiele's family, featured in a 2023 exhibition "Egon Schiele. Me!", suggests that there is still more to learn about the personal dynamics and intimate details of their circle. Such firsthand accounts are invaluable for art historians, offering nuances and perspectives that might be lost in more formal records. These interviews could shed further light on Peschka's personality, his specific contributions to discussions within the Neukunstgruppe, and the nature of his artistic dialogue with Schiele.

The mention of Peschka's support for social causes, such as children's lunch programs, paints a picture of an artist engaged with the societal issues of his time, extending his concerns beyond the purely aesthetic realm. This adds another dimension to his biography, portraying him not just as a painter but as a socially conscious individual.

Legacy and Historical Evaluation

Anton Emanuel Peschka's legacy is that of a dedicated Austrian painter who was an active participant in the birth of Expressionism in Vienna. He was a skilled colorist and a sensitive interpreter of landscapes and still lifes. His close association with Egon Schiele, one of the giants of 20th-century art, inevitably means that his own artistic achievements are often viewed through that prism. However, this association also provides a rich context for understanding his work and his place in art history.

He is remembered as a loyal friend and collaborator, a member of the rebellious Neukunstgruppe, and an artist who, while perhaps not possessing Schiele's radical genius or Kokoschka's dramatic intensity, contributed meaningfully to the diverse tapestry of Austrian modernism. His work offers a more lyrical, and at times decorative, counterpoint to the often-anguished intensity of his more famous contemporaries, yet it remains firmly rooted in the expressive and subjective ethos of the era.

His paintings, when they appear at auctions or in exhibitions, serve as a reminder of the vibrant artistic community that flourished in Vienna in the early 1900s and of the many talented individuals who contributed to its dynamism. Anton Peschka's art, characterized by its expressive use of color and its engagement with the Austrian landscape and artistic traditions, holds a secure, if modest, place in the annals of Austrian art history. He remains a figure worthy of study, both for his intrinsic artistic merits and for the light his life and work shed on the extraordinary artistic milieu of early 20th-century Vienna and its most celebrated protagonists.