Franz Sedlacek stands as a distinctive and somewhat enigmatic figure in early 20th-century Austrian art. An artist whose career was tragically cut short by war, he navigated a path between scientific precision and fantastical imagination, leaving behind a body of work that continues to intrigue and resonate. His paintings, often imbued with an unsettling quietude and a meticulous, almost hyper-realistic detail, place him firmly within the New Objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit) movement, yet with a unique flavour of magic realism and surreal undertones that set him apart. This exploration delves into the life, art, and enduring legacy of Franz Sedlacek, examining his key works, his associations, and his place within the turbulent artistic and historical currents of his time.

Early Life and Formative Years

Franz August Sedlacek was born on January 21, 1891, in Breslau, Silesia (now Wrocław, Poland), into a family that would soon relocate to Linz, Austria, in 1897. This move to Upper Austria would prove significant, as Linz became a central hub for his early artistic activities. His father, Julius Reichard Sedlaczek, was a manufacturer of refrigeration machines, suggesting a household where technical and practical matters were likely valued. From a young age, Sedlacek displayed a talent for drawing and caricature, hinting at the artistic path he would eventually follow.

Despite this early inclination towards art, Sedlacek pursued a more conventional academic route. In 1909, he moved to Vienna to study architecture at the Technische Hochschule (Technical University). However, a year later, in 1910, he switched his field of study to chemistry. This scientific background, particularly in chemistry, is often cited as a subtle influence on his later painting technique, which was characterized by meticulous detail, smooth surfaces, and a precise application of paint, almost akin to the careful processes of a laboratory. He successfully completed his chemistry studies in 1921, after an interruption due to war service.

Alongside his technical studies, Sedlacek continued to nurture his artistic talents. He was largely self-taught as a painter, developing his skills through personal exploration and practice rather than formal academic art training. This independent development may have contributed to the unique and somewhat idiosyncratic style he later forged.

Artistic Beginnings and the MAERZ Collective

Even before completing his chemistry degree, Sedlacek was actively involved in the art scene. In 1913, a pivotal year for his early artistic career, he co-founded the Linz-based artists' association known as MAERZ (derived from the German word for March, symbolizing a new beginning or spring in art). His fellow co-founders included notable local artists such as Anton Lutz, Klemens Brosch, Franz Bitzan, and Heinz Bitzan. MAERZ aimed to provide a platform for modern artistic expression in Linz and became an important regional artistic group.

Sedlacek's early works often consisted of humorous graphics and illustrations for magazines like "Die Muskete" and "Simplicissimus," showcasing his skill in caricature and a keen observational wit. These early forays into graphic art honed his draftsmanship and ability to convey narrative and character succinctly. However, his artistic development was, like that of many of his generation, profoundly impacted by the outbreak of World War I. Sedlacek served in the military from 1914 to 1918, an experience that undoubtedly shaped his worldview and perhaps contributed to the darker, more melancholic undertones found in some of his later works.

After the war, Sedlacek returned to Vienna. In 1921, he began working at the Technisches Museum Wien (Vienna Technical Museum). His scientific background served him well here, and he eventually rose to become the head of the Department of Chemical Industry by 1937. This dual career, balancing a demanding professional life in a scientific institution with a dedicated artistic practice, is a testament to his discipline and passion for painting. He married Maria Albrecht in 1923, and the couple had two daughters, further grounding his life outside the studio.

The Emergence of a Unique Style: New Objectivity and Magic Realism

By the 1920s, Franz Sedlacek had developed a mature and highly distinctive painting style. He became a prominent representative of the New Objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit) movement in Austria. This art movement, which flourished primarily in Germany during the Weimar Republic as a reaction against the emotionalism of Expressionism and the abstraction of other avant-garde movements, sought a return to objective reality. Artists like George Grosz and Otto Dix in Germany used this style for sharp social critique, while others like Alexander Kanoldt and Georg Schrimpf focused on meticulously rendered, often static, depictions of everyday objects and landscapes.

Sedlacek's version of New Objectivity was less about direct social satire and more imbued with a sense of unease, mystery, and the fantastical. His works often share characteristics with Magic Realism, a term sometimes used interchangeably or in close conjunction with certain facets of New Objectivity. Magic Realism depicts realistic views of the world while adding magical or dreamlike elements, creating a sense of wonder, bewilderment, or quiet dread. Sedlacek's paintings masterfully blend the mundane with the bizarre, the familiar with the uncanny. His landscapes are often desolate and eerie, populated by strange figures or imbued with an almost palpable sense of foreboding.

His technique was meticulous, characterized by a smooth, enamel-like finish, precise lines, and a careful layering of glazes, which gave his colours a deep luminosity. This painstaking approach, possibly influenced by his chemical training and an appreciation for Old Master techniques, contributed to the unsettling clarity of his visions. His compositions are often carefully structured, with a strong sense of atmosphere, frequently depicting twilight or nocturnal scenes that enhance their mysterious quality.

Key Themes and Representative Works

Franz Sedlacek's oeuvre is rich with recurring themes and iconic images that encapsulate his unique artistic vision. His subjects range from haunting landscapes and industrial scenes to peculiar genre paintings and allegorical compositions.

One of his most famous and emblematic paintings is "Gespenster auf dem Baum" (Ghosts on a Tree, 1933). This work depicts several gaunt, spectral figures, resembling emaciated birds or tormented souls, perched precariously on the branches of a barren tree against a moody, atmospheric sky. The painting evokes a profound sense of desolation and impending doom, a chilling premonition perhaps of the dark times that were engulfing Europe. The meticulous rendering of the gnarled tree and the ethereal yet unsettling forms of the ghosts creates a powerful and unforgettable image.

Another significant work, "Der Chemiker" (The Chemist, 1932), offers a glimpse into a world Sedlacek knew well. However, this is no straightforward depiction of a scientist at work. The chemist, hunched over his apparatus in a dimly lit laboratory, seems engaged in some arcane, almost alchemical process. The atmosphere is one of intense concentration mixed with an element of the sinister or the secretive. The play of light and shadow, and the precise rendering of glassware and equipment, highlight Sedlacek's technical skill while imbuing the scene with a palpable tension.

"Landschaft mit Regenbogen" (Landscape with Rainbow, 1930) showcases his ability to transform a seemingly ordinary landscape into something extraordinary and unsettling. While a rainbow typically symbolizes hope, in Sedlacek's hands, set against a dark, brooding sky and an unnaturally lit, deserted terrain, it takes on an almost ominous quality. The precision of the details and the heightened reality of the scene are characteristic of his magic realist tendencies.

His "Ananasbild" (Pineapple Picture), which reportedly depicts the royal reception of King Charles II with a pineapple, demonstrates his ability to infuse historical or anecdotal scenes with his peculiar style. While the exact painting referred to by this title in the provided information might require further specific identification from his catalogue raisonné, Sedlacek did create works that played with narrative and unusual juxtapositions.

"Waldlandschaft mit Jäger" (Forest Landscape with a Hunter, 1928) is another example of his atmospheric landscapes. The hunter, often a solitary figure in his work, moves through a meticulously detailed yet strangely stylized forest. The interplay of light filtering through the trees and the sense of deep, quiet wilderness are rendered with a precision that paradoxically enhances the scene's dreamlike quality.

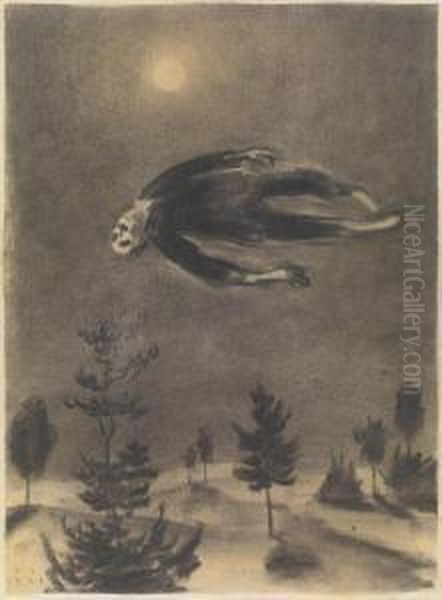

Other notable works that further illustrate his style include "Lied in der Dämmerung" (Twilight Song) and "Gespenst über den Bäumen" (Spectre above the Trees), both titles suggesting his preoccupation with crepuscular atmospheres and supernatural or unsettling elements. These paintings often feature vast, empty spaces, dramatic skies, and a sense of isolation that can be both beautiful and disturbing. His figures, when present, often appear small and vulnerable against the backdrop of these imposing, psychologically charged environments.

The Vienna Secession and Wider Recognition

Sedlacek's growing reputation led to his involvement with one of Austria's most prestigious art institutions. In 1927, he became a full member of the Vienna Secession. Founded in 1897 by artists like Gustav Klimt, Koloman Moser, and Josef Hoffmann, the Secession had initially championed Art Nouveau (Jugendstil) and sought to break away from academic historicism. By the 1920s, while its initial revolutionary zeal had evolved, it remained a vital forum for contemporary Austrian art, encompassing a broader range of styles. Sedlacek's membership signified his acceptance into the upper echelons of the Austrian art world. He regularly participated in the Secession's exhibitions, bringing his unique vision to a wider audience.

His work began to gain international recognition as well. He exhibited in various European cities and even in the United States. A significant accolade came in 1929 when he was awarded a gold medal at the World Exhibition in Barcelona for his contributions to art. He also received the Austrian State Prize for painting on multiple occasions (e.g., 1930, 1937), further cementing his status as a leading Austrian artist of his generation. He participated in exhibitions such as the "Austrian Art Exhibition" in Vienna in 1924 and, with artists like Herbert Plochinger and Paul Ikrath, in the "Romanticism and New Objectivity" exhibition in Linz. In 1930, his work was featured in the "Modern Austrian Painting" exhibition at The Renaissance Society in Chicago.

During this period, Sedlacek also formed important artistic friendships. Around 1928, he became close friends with the painter Herbert von Reyl-Hanisch, another Austrian artist whose work sometimes shared a similar meticulousness and atmospheric quality, though often with a different thematic focus. Such connections provided a supportive network and intellectual exchange crucial for artistic development.

The Shadow of War: Military Service and Intelligence Work

The rise of Nazism and the ensuing political turmoil of the 1930s cast a long shadow over Europe, and Franz Sedlacek's life and career were not immune to these forces. In 1939, with the outbreak of World War II, Sedlacek was drafted into the Wehrmacht (the German armed forces, following Austria's Anschluss in 1938). He served as an officer, and his military duties took him to various fronts, including participation in the brutal Battle of Stalingrad, as well as campaigns in Norway and Poland.

The provided information mentions an accusation of Nazi party membership, but also notes that this is disputed. It's a complex aspect of his biography that requires careful consideration of historical evidence. Many Austrians faced immense pressure or saw opportunities in aligning with the Nazi regime after the Anschluss. Without definitive, corroborated evidence, it remains a contentious point.

More intriguing, and perhaps less widely known, is Sedlacek's alleged involvement in intelligence work during the war. According to some accounts, he served as an intelligence officer. He reportedly worked in Brno (in the then-Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia) and was later transferred to Prague for training in radio signal operations, secret writing, and code decryption. It is suggested that he used a journalist's identity as a cover and reported intelligence to London, even establishing contact with a Swiss intelligence officer named Hans Hausmann. If accurate, this paints a picture of a far more complex wartime role than simply that of a regular soldier, suggesting a dangerous double life. This aspect of his biography adds another layer of mystery to his persona.

His artistic production inevitably suffered during these years of conflict and upheaval. The demands of military service and the harsh realities of war were far removed from the quiet, meticulous work of his studio.

The Final Years and Mysterious Disappearance

Franz Sedlacek's life came to a tragic and unresolved end in the final chaotic months of World War II. In January 1945, while serving as a Wehrmacht officer, he went missing in action near Toruń (Thorn) in Poland during the Soviet Vistula-Oder Offensive. The exact circumstances of his disappearance remain unknown. For many years, his fate was uncertain, and it was not until 1972 that he was officially declared legally dead, with the presumptive date of death often cited as 1945.

This mysterious end contributes to the enigmatic aura surrounding Sedlacek. Like the spectral figures in his paintings, he vanished into the fog of war, leaving behind a legacy captured in his unsettling and meticulously crafted artworks.

Legacy and Historical Evaluation

Franz Sedlacek's artistic output, though not vast due to his dual career and premature death, is highly significant. He is considered one of Austria's foremost exponents of New Objectivity and Magic Realism. His work stands out for its technical brilliance, its imaginative power, and its ability to evoke profound psychological states and atmospheric tension.

In the post-war period, Sedlacek's work, like that of many artists associated with New Objectivity, experienced a period of relative obscurity as Abstract Expressionism and other modernist trends came to dominate the art world. However, there has been a significant resurgence of interest in his art in recent decades. His paintings are now highly sought after by collectors and are featured in major museum collections, including the Leopold Museum and the Albertina in Vienna, which hold significant examples of his work.

His art is appreciated for its unique blend of precision and fantasy. The unsettling, dreamlike quality of his paintings resonates with contemporary audiences, perhaps reflecting a shared sense of anxiety and uncertainty in the modern world. Art historians recognize his contribution to the diversity of interwar European art, offering a distinct Austrian perspective within the broader currents of New Objectivity. His work can be seen in dialogue with other artists who explored similar themes of unease and the uncanny, such as the Belgian Surrealist René Magritte, whose meticulously rendered paradoxes share a certain intellectual coolness with Sedlacek's visions, or even the more overtly nightmarish landscapes of Salvador Dalí, though Sedlacek's approach was generally more subdued and rooted in a semblance of reality.

Within Austria, his work can be compared to contemporaries like Albert Birkle, who also worked in a magic realist vein, or even earlier figures from the Vienna Secession like Alfred Kubin, whose graphic work explored themes of fantasy, death, and the grotesque, albeit with a more expressionistic line. While stylistically different, the pioneering spirit of Gustav Klimt and the raw intensity of Egon Schiele had already established Vienna as a crucible for innovative and psychologically charged art, a legacy that Sedlacek, in his own way, continued. His German New Objectivity counterparts like Otto Dix, George Grosz, and Max Beckmann often engaged in more direct and savage social critique, whereas Sedlacek's commentary was typically more allegorical and introspective. Christian Schad, another German New Objectivity artist, shared Sedlacek's cool precision but focused more on portraits that captured the zeitgeist of the Weimar era.

The recent interest in his work has also extended to the digital realm, with his style reportedly inspiring AI art generators, a testament to the distinctive and recognizable qualities of his visual language.

Sedlacek in Context: Contemporaries and Influences

To fully appreciate Franz Sedlacek, it's essential to view him within the rich tapestry of European art during the first half of the 20th century. His direct associates in the MAERZ group, such as Anton Lutz and Klemens Brosch, were part of his immediate artistic environment in Linz, fostering a local modern art scene. His friendship with Herbert von Reyl-Hanisch in Vienna further indicates his connections within the Austrian capital's art circles.

The broader New Objectivity movement provided the primary context for his mature style. In Germany, artists like George Grosz and Otto Dix were using sharp, often grotesque realism to critique the corruption and social disparities of the Weimar Republic. Max Beckmann, while often associated with Expressionism, also developed a powerful, symbolic figuration that had affinities with New Objectivity's desire for tangible form. Christian Schad was known for his coolly detached, meticulously detailed portraits, while Alexander Kanoldt and Georg Schrimpf represented a more classicizing, almost magical realist wing of the movement, focusing on still lifes and landscapes with an unnerving stillness that resonates with Sedlacek's work.

While Sedlacek was not a Surrealist in the formal sense of André Breton's manifestos, his work shares certain affinities with the movement's exploration of the subconscious, dreams, and the uncanny. The meticulous realism combined with illogical or fantastical elements found in the works of René Magritte or the dreamscapes of Salvador Dalí and Max Ernst offer points of comparison, highlighting the period's fascination with realities beyond the immediately visible.

Within Austria, the legacy of the Vienna Secession, founded by Gustav Klimt, was profound. Though Sedlacek joined much later, the Secession's spirit of artistic renewal and its openness to diverse modern styles provided a fertile ground. Other Austrian artists of the era, such as the expressionist Oskar Kokoschka or the aforementioned Alfred Kubin (known for his dark, symbolic drawings), contributed to a vibrant, if often angst-ridden, artistic climate. Albert Birkle, another Austrian painter, is perhaps one of the closest parallels to Sedlacek in terms of a shared tendency towards Magic Realism, often depicting melancholic or eerie scenes with a similar detailed technique.

Sedlacek's unique position stems from his synthesis of these influences – the precision of New Objectivity, the imaginative freedom of Magic Realism, and a deeply personal, often melancholic vision – all filtered through his meticulous, almost scientific approach to painting.

Conclusion

Franz Sedlacek remains a compelling and somewhat mysterious figure in art history. A man of science and art, his paintings bridge the gap between the observable world and the landscapes of the imagination. His meticulously crafted scenes, filled with eerie beauty, quiet dread, and enigmatic narratives, secure his place as a significant Austrian contributor to the New Objectivity and Magic Realism movements. His life, marked by the turbulence of two world wars and ending in a still-unexplained disappearance, adds a layer of poignant tragedy to his artistic legacy. As his work continues to be rediscovered and appreciated, Franz Sedlacek's singular vision offers a timeless exploration of the anxieties, dreams, and hidden realities that lie beneath the surface of the everyday. His art is a quiet but powerful testament to the enduring human need to make sense of a world that is often both beautiful and terrifying.