Antonio Mercurio Amorosi stands as a notable figure in the landscape of Italian art during the late Baroque period. Born in 1660 in Comunanza, a town nestled in the Marche region of Italy, specifically within the province of Ascoli Piceno, Amorosi carved a niche for himself primarily in Rome, the bustling artistic heart of the era. His long life, concluding in 1738 back in his hometown of Comunanza at the age of 78, spanned a dynamic period in art history. He is best remembered as a painter who skillfully navigated the demands of patronage while developing a distinct voice, particularly in the realm of genre painting, but also contributing significantly to portraiture and religious art.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Rome

Amorosi's journey into the world of art was not a foregone conclusion. Sources suggest that his initial aspirations leaned towards a life in the clergy. However, a burgeoning interest in the visual arts ultimately redirected his path. Making a pivotal move, he relocated to Rome in 1686 (some sources suggest an earlier date of 1668, but 1686 aligns with his likely apprenticeship period). This decision placed him at the epicenter of artistic innovation and patronage in Italy.

In Rome, the young artist sought formal training. He entered the studio of Giuseppe Ghezzi (1634-1721), a respected painter and a prominent figure in the Roman art establishment, known for his altarpieces and his role in the Accademia di San Luca. Training under Ghezzi would have exposed Amorosi to the prevailing artistic currents of the late Baroque, emphasizing solid draughtsmanship, dynamic composition, and the effective use of light and shadow, principles deeply rooted in the Roman tradition tracing back to masters like Caravaggio and Annibale Carracci, albeit filtered through the sensibilities of the later 17th century.

The Development of a Distinctive Style: Bambocciate and Beyond

While his initial training likely focused on the more conventional history and religious painting favoured by the academies, Amorosi soon found his forte in genre scenes, particularly the style known as bambocciate. This term, derived from the nickname 'Il Bamboccio' (Big Baby or Puppet) given to the Dutch painter Pieter van Laer who popularized such themes in Rome earlier in the 17th century, referred to paintings depicting the everyday lives of ordinary people – peasants, artisans, street vendors, often children at play or engaged in simple tasks.

Amorosi embraced this tradition, infusing it with his own sensibility. His genre works are characterized by a keen observation of daily life, often rendered with a sympathetic, sometimes humorous or gently satirical, eye. He excelled at capturing the unposed moments, the textures of rustic clothing, and the simple environments of his subjects. His style retained Baroque elements, particularly in the use of light and shadow (chiaroscuro) to model forms and create atmosphere, but often tempered the high drama associated with the grand manner of Baroque history painting.

His brushwork is typically detailed and refined, allowing for a clear depiction of figures and objects. There's a naturalism in his approach that makes his scenes relatable and engaging. While influenced by the Northern European tradition of genre painting brought to Italy by artists like Van Laer and Michelangelo Cerquozzi, Amorosi's work possesses an distinctly Italian character, perhaps softer and more idealized than some of its Northern counterparts. Some accounts suggest a stylistic evolution, possibly moving from more 'heroic' early attempts towards the more intimate and popular bambocciate style that garnered him considerable success.

Themes and Subject Matter: A Versatile Painter

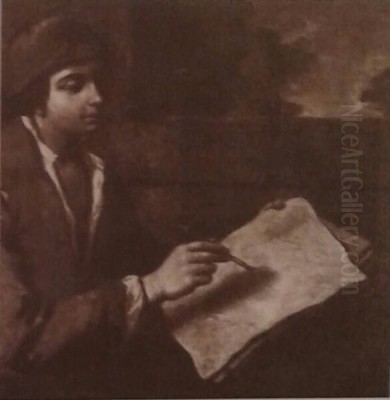

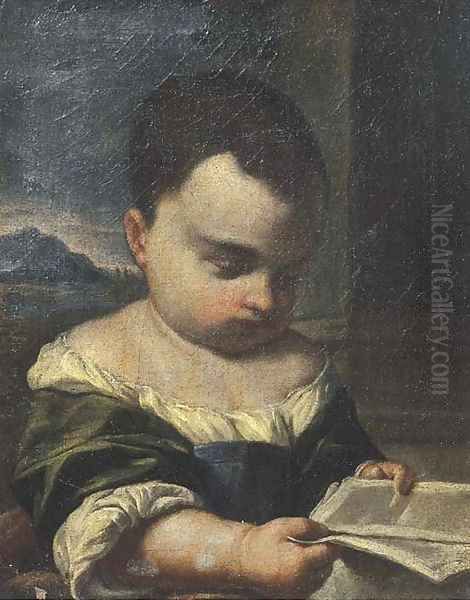

Amorosi's reputation largely rests on his genre paintings. He frequently depicted children – playing games, learning lessons, or simply captured in moments of quiet contemplation. These works often possess a charm and tenderness that appealed greatly to collectors. Scenes of humble domestic life, musicians, and street characters also feature prominently in his oeuvre. These paintings provide valuable visual records of the customs, clothing, and social strata of his time, viewed through the lens of Baroque artistry.

However, Amorosi was not solely a painter of bambocciate. He was also a capable portraitist. While perhaps less numerous than his genre scenes, his portraits would have catered to the demands of Roman patrons, capturing likenesses and conveying the status of his sitters, likely employing the sophisticated techniques learned during his training.

Furthermore, Amorosi engaged with religious themes, demonstrating his versatility. He is known to have painted altarpieces and devotional images, such as depictions of the Madonna. Though perhaps less central to his fame today, these works were an important part of a painter's output in Baroque Rome, fulfilling commissions for churches and private patrons seeking objects of piety. This aspect of his work highlights his ability to adapt his skills to different artistic requirements and contexts.

Key Works and Masterpieces

Several works stand out as representative of Antonio Amorosi's artistic production and style. Among his most celebrated genre paintings is the Girl with a Cluster of Grapes. Housed in the Nationalmuseum in Stockholm, this painting exemplifies his skill in rendering youthful charm and naturalistic detail. The subject, a young girl holding grapes, is depicted with sensitivity, showcasing Amorosi's delicate brushwork and his ability to capture textures, from the soft skin of the girl to the bloom on the fruit, all bathed in characteristic Baroque lighting.

Another frequently cited work is the Girl with Jewelry. While its current primary location might be debated (sometimes associated with the Pompidou Centre, Paris, among other collections), its existence points to his interest in portraying young figures, perhaps hinting at allegorical meanings or simply celebrating youthful innocence adorned with trinkets. Such works highlight the detailed rendering and appealing subject matter that made his genre scenes popular.

His An Allegory of Smell, mentioned in art historical literature, represents his engagement with allegorical themes within a genre context, showcasing a mature Baroque style characterized by compositional clarity and an appreciation for natural detail. Furthermore, the high value achieved by works like Young Girl Reading, reportedly selling for a significant sum at auction, attests to the enduring appeal and market recognition of his paintings, particularly those capturing intimate, quiet moments. These specific examples underscore the qualities that defined his contribution: technical finesse, charming subject matter, and a mastery of Baroque aesthetics applied to everyday scenes.

Patronage and Reception in Rome

Amorosi's success, particularly with his genre paintings, indicates that he found favour among Roman patrons and collectors. The aristocracy and wealthy clergy of Rome were significant consumers of art, and the fashion for bambocciate, while sometimes looked down upon by academic purists, provided a steady market. These smaller-scale, often charming or intriguing scenes of everyday life were well-suited to private collections and domestic interiors.

Specific patrons are sometimes mentioned, such as the Duke of Uceda, a Spanish nobleman who served as ambassador to the Holy See. Association with such figures indicates Amorosi's integration into the higher echelons of Roman society and the art market. His ability to capture appealing scenes with technical proficiency ensured his popularity. The demand for his work suggests that his blend of naturalistic observation and Baroque technique resonated with the tastes of the time, offering a less grandiose, more intimate alternative to the large-scale history paintings dominating church and palace decorations.

Amorosi and His Contemporaries: The Roman Art Scene

Antonio Amorosi operated within a vibrant and competitive artistic environment in Rome. His teacher, Giuseppe Ghezzi, was a central figure, and Amorosi would have undoubtedly known many other artists associated with Ghezzi's circle and the Accademia di San Luca. This included Ghezzi's son, Pier Leone Ghezzi, who gained fame for his paintings and, notably, his caricatures, offering a different, often satirical, perspective on Roman life.

When Amorosi arrived and established himself, the dominant figure in Roman painting was Carlo Maratta, whose classical Baroque style set the tone. Other major contemporaries included Baciccio (Giovanni Battista Gaulli), renowned for his breathtaking illusionistic ceiling frescoes, and later figures like Sebastiano Conca and Francesco Trevisani, who carried the Baroque tradition into the 18th century with large decorative schemes and elegant portraits. Benedetto Luti was another prominent painter known for his smooth finish and colour palette. Towards the end of Amorosi's life, Pompeo Batoni was beginning his ascent, becoming a favourite portraitist for Grand Tour travellers.

Amorosi's focus on bambocciate placed him in a lineage that included the aforementioned Pieter van Laer and Michelangelo Cerquozzi. His work also invites comparison, and sometimes confusion, with other painters exploring similar themes or styles. Notably, his paintings have occasionally been misattributed to the Bolognese master Giovanni Maria Crespi, whose genre scenes share a certain earthy realism, and perhaps more frequently to Bernhard Keil (known as Monsù Bernardo in Italy), a Danish painter who worked in Italy and often depicted allegorical and genre subjects with a similar focus on textures and light. These comparisons and occasional confusions highlight the shared artistic currents of the time but also underscore the need for careful connoisseurship in distinguishing Amorosi's specific hand and style. He navigated this complex scene, finding his niche and contributing his unique perspective alongside these diverse talents.

Attribution Issues and Scholarly Interest

The occasional misattribution of Amorosi's works, particularly to Bernhard Keil or Giovanni Maria Crespi, points to challenges inherent in studying artists who may not have consistently signed their works or whose styles shared common ground with contemporaries. Workshop practices, where assistants might replicate popular compositions, could also contribute to attribution difficulties. Disentangling the precise authorship of certain genre paintings from this period requires careful stylistic analysis and comparison.

Despite these challenges, Amorosi did not fade into obscurity. His life and work were documented relatively early on by the art historian and biographer Lionello Pascoli in his Vite de' pittori, scultori ed architetti moderni (Lives of Modern Painters, Sculptors, and Architects), published in the 1730s. Pascoli's account provides valuable contemporary insights into Amorosi's career, his training under Ghezzi, his specialization in genre scenes featuring children and rural life, and his popularity among patrons, including the Duke of Uceda. This early biographical attention helped secure Amorosi's place in the historical record. Modern scholarship continues to refine our understanding of his oeuvre, distinguishing his works from those of his contemporaries and appreciating his specific contribution to the diverse tapestry of Baroque art.

Later Life and Legacy

After a long and productive career centered largely in Rome, Antonio Amorosi eventually returned to his place of birth, Comunanza, in the Marche region. He passed away there in 1738, leaving behind a substantial body of work. His legacy lies primarily in his contribution to Italian genre painting during the late Baroque era.

He successfully adapted the bambocciate tradition, infusing it with a characteristic charm, technical refinement, and sensitive observation. While perhaps not reaching the monumental scale or dramatic intensity of some Baroque history painters, Amorosi excelled in capturing the nuances of everyday life, particularly the world of children and the rural populace. His paintings offered patrons intimate glimpses into ordinary existence, rendered with the sophisticated techniques of Baroque naturalism and chiaroscuro. He remains an important figure for understanding the diversity of artistic production in Rome and the enduring appeal of genre themes that provided a counterpoint to the grand religious and mythological narratives dominating official art.

Conclusion: A Master of Intimate Baroque

Antonio Amorosi navigated the complex art world of late Baroque Rome to become a recognized master, particularly cherished for his depictions of everyday life. From his training under Giuseppe Ghezzi to his successful career catering to Roman patrons, he developed a distinctive style that blended Baroque techniques with sensitive, naturalistic observation. His focus on bambocciate, especially scenes involving children, showcased his skill in capturing intimate moments with charm and technical finesse. While also proficient in portraiture and religious subjects, it is his genre paintings, celebrated by contemporaries like Lionello Pascoli and valued by collectors then and now, that secure his legacy as a significant chronicler of the human condition within the vibrant artistic landscape of his time.