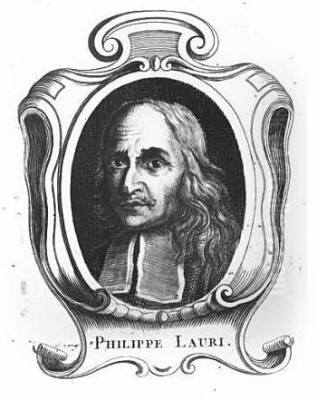

Filippo Lauri stands as a significant figure in the vibrant artistic landscape of seventeenth-century Rome. Born in the heart of the city in 1623 and active throughout the high Baroque period until his death in 1694, Lauri carved a distinct niche for himself. He was celebrated for his refined mythological and religious paintings, often executed on a smaller scale suitable for private collectors, yet he also contributed to larger decorative schemes. His work embodies many key characteristics of the Baroque era – drama, emotion, and ornate detail – while maintaining a certain elegance and narrative clarity that appealed to sophisticated patrons.

Lauri's life and career were deeply intertwined with the artistic currents of Rome. He navigated a world populated by towering figures like Gian Lorenzo Bernini and Pietro da Cortona, yet developed his own recognizable style. He was not only a painter but also an active member and eventual head of the prestigious Accademia di San Luca, underscoring his respected position within the Roman art establishment. Exploring his journey reveals insights into artistic training, patronage, collaboration, and the thematic preoccupations of the Baroque age in Italy.

Artistic Roots and Early Training

Filippo Lauri's artistic lineage was notable. He was born into an artistic family in Rome, the son of Balthasar Lauwers, a Flemish landscape painter who had settled in Italy and Italianized his name to Lauri. Balthasar himself had trained under the influential Flemish landscape specialist Paul Bril, known for his work in Rome. This connection provided young Filippo with an early exposure to the Northern European landscape tradition, albeit filtered through an Italian lens.

His initial artistic instruction came from his father. However, his primary teacher was his elder brother, Francesco Lauri. Francesco had studied with Andrea Sacchi, a leading painter in Rome known for his more classical and restrained approach to Baroque art, contrasting somewhat with the high drama of contemporaries like Pietro da Cortona. This connection to Sacchi's circle likely imparted a sense of compositional order and clarity to Filippo's developing style.

Further formative experience came through his association with Angelo Caroselli, a painter known for his eclectic style and sometimes enigmatic subject matter. Lauri worked in Caroselli's studio, who was also his brother-in-law. Sources suggest Lauri may have initially functioned as a copyist there, a common practice for young artists honing their skills. He remained associated with Caroselli's workshop until Caroselli's death in 1652, absorbing influences and techniques within that environment. This varied training—rooted in Flemish landscape, guided by Sacchi's classicism via his brother, and exposed to Caroselli's unique style—provided Lauri with a diverse foundation upon which to build his independent career.

Emergence in the Roman Art Scene

By the early 1650s, following the death of Angelo Caroselli, Filippo Lauri began to establish himself as an independent master. A significant milestone occurred in 1654 when he was admitted into the prestigious Accademia di San Luca, Rome's official academy of artists. Membership signified professional recognition and integrated him more fully into the city's artistic community. It provided opportunities for networking, securing commissions, and participating in the institutional life of Roman art.

During the 1650s, Lauri started receiving commissions from important patrons in Rome. While he became particularly known for his smaller, meticulously crafted cabinet paintings, often on copper or panel, he also demonstrated his ability to work on a larger scale. His skills were sought after for decorative projects within the opulent palaces of the Roman aristocracy and clergy. These commissions often involved mythological or allegorical themes, perfectly suited to the lavish interiors of Baroque residences.

His reputation grew steadily. He became known for his reliability, his refined technique, and his ability to imbue narrative scenes with life and charm. His works entered prominent collections, solidifying his status as a sought-after painter within the competitive Roman art market. His acceptance into the Academy was not merely a formality; it marked the beginning of a long and respected career operating at the heart of Baroque Rome.

Style and Thematic Focus: The Baroque Narrative

Filippo Lauri's art is firmly rooted in the Baroque style, yet possesses its own distinct characteristics. He embraced the era's love for drama, dynamic compositions, and rich emotional content. However, his work often displays a greater degree of delicacy and refinement compared to the more monumental or turbulent creations of some contemporaries. His figures are typically elegant, his colours often bright and harmonious, and his handling of paint precise.

Mythology was a cornerstone of Lauri's output. He excelled at depicting scenes from classical antiquity, drawing heavily on Ovid's Metamorphoses and other ancient sources. These subjects allowed him to explore dramatic narratives, human emotions, and the beauty of the idealized human form. Works like Apollo Flays Marsyas and The Rape of Europa showcase his ability to render these ancient tales with vividness and psychological insight, capturing moments of divine power, human hubris, or tragic love.

Religious themes also formed a significant part of his oeuvre, treated with the same narrative flair and attention to detail. Whether depicting biblical stories or the lives of saints, Lauri infused these scenes with Baroque dynamism and emotional resonance. His style, characterized by its ornate qualities and theatricality, aligned well with the Counter-Reformation's emphasis on art that could inspire piety and awe through compelling visual storytelling. Light and shadow (chiaroscuro) were employed effectively to model forms and heighten the dramatic impact of his compositions.

Masterpieces of Myth and Allegory

Several key works exemplify Filippo Lauri's skill in mythological and allegorical painting. His rendition of Venus and Adonis is a prime example of his approach to classical themes. The painting captures the poignant moment from the myth, often focusing on Venus's desperate love for the mortal hunter Adonis, perhaps foreshadowing his tragic end. Lauri typically emphasizes the emotional intensity, using gestures and expressions to convey the narrative. The presence of Cupid, often shown actively involved, underscores the themes of love and fate, adding a dynamic element typical of Baroque interpretation.

Another fascinating mythological work is Chelone Transforming into a Turtle. This painting depicts a lesser-known myth concerning the nymph Chelone (or Hecate in some versions), who was punished by the gods – typically Jupiter and Juno, or Hermes acting on their behalf – for refusing to attend their wedding or for mocking the occasion. Her punishment was transformation into a turtle, forever carrying her home on her back. Lauri's depiction likely focused on the moment of transformation, capturing Chelone's regret or anguish. Such subjects allowed artists like Lauri to showcase their skill in rendering expressive figures and dramatic action, while potentially embedding moral lessons about piety and respect for divine authority, reflecting societal norms.

Beyond specific myths, Lauri often created idyllic Bacchanales or scenes featuring nymphs, satyrs, and classical deities in lush landscapes. Works like Bacchanale with offrande au Dieu Pan demonstrate his ability to create lively, multi-figure compositions celebrating sensuous pleasure and the power of nature, themes popular among collectors of cabinet paintings. These works highlight his decorative sensibilities and his skill in integrating figures harmoniously within landscape settings.

Collaboration: A Networked Artist

A notable aspect of Filippo Lauri's career was his frequent collaboration with other artists, particularly landscape specialists. In the seventeenth century, it was common for painters to specialize, and collaborations allowed artists to combine their respective strengths. Lauri gained renown for his skill in painting small, lively figures, known as staffage, which added narrative interest and scale to landscape paintings.

One of his most significant collaborators was the celebrated French landscape painter Claude Lorrain, who spent most of his career in Rome. Lauri is documented as having painted the figures in some of Lorrain's idealized classical landscapes. This partnership speaks volumes about Lauri's reputation, as Lorrain was highly selective about who contributed to his masterpieces. The delicate, well-drawn figures Lauri provided complemented Lorrain's atmospheric and light-filled landscape visions perfectly.

Lauri also worked closely with Gaspard Dughet, another prominent landscape painter active in Rome (and Nicolas Poussin's brother-in-law). Together, they produced works where Dughet's evocative landscapes provided the setting for Lauri's mythological or biblical figures. Examples include paintings like Naissance d'Adonis (The Birth of Adonis) and potentially collaborative landscape projects involving allegorical themes like the seasons, such as Sketches for Spring and Winter. These collaborations showcased Lauri's adaptability and his ability to harmonize his figures with another artist's style.

Further collaborations are recorded. He worked with the architectural painter Filippo Gagliardi on a notable painting depicting the festivities held at the Palazzo Barberini in honour of Queen Christina of Sweden's arrival in Rome. This complex work required integrating numerous figures within an elaborate architectural setting, demonstrating Lauri's skill in handling large-scale, populated scenes. He also collaborated with the flower painter Mario Nuzzi, known as 'Mario de' Fiori', contributing figures to Nuzzi's lush floral compositions, such as in the allegorical painting La Primavera (Spring, 1658-1659). These partnerships highlight Lauri's versatility and his central role within the interconnected network of artists in Baroque Rome.

The Accademia di San Luca and Roman Commissions

Filippo Lauri's involvement with the Accademia di San Luca was more than just nominal membership. He was deeply engaged with the institution, eventually rising to its highest position. In 1684, he was elected Principe (Principal or President) of the Academy, a prestigious honour that reflected the high esteem in which he was held by his peers. Serving as Principe placed him at the forefront of Rome's official art world, involved in its governance, educational activities, and upholding its standards.

His status and skill led to significant commissions beyond easel paintings. He was involved in decorating some of Rome's most important palaces. Records indicate his work for prominent families like the Borghese and the Colonna. For the Palazzo Borghese, he is known to have contributed to decorative schemes, potentially including ceiling designs or frescoes. His work for the Palazzo Colonna further cemented his reputation among the Roman nobility.

His collaboration with Filippo Gagliardi on the painting commemorating Queen Christina's reception at the Palazzo Barberini, commissioned by the powerful Barberini family, was another high-profile project. While perhaps best known today for his cabinet pictures, these larger-scale commissions demonstrate Lauri's capacity to undertake ambitious decorative projects demanded by elite patrons. He also practiced printmaking, creating etchings that helped disseminate his compositions to a wider audience. His activity across different scales and media, coupled with his leadership role in the Academy, paints a picture of a well-respected and fully integrated member of the Roman artistic establishment.

Teaching, Influence, and Contemporaries

As a respected master and Principe of the Accademia di San Luca, Filippo Lauri likely played a role in educating the next generation of artists, although specific details about his workshop structure or numerous pupils are not always clear. The snippets mention younger painters like Pietro Testa and possibly Francesco Morante (perhaps Pier Francesco Mola?) as being associated with him or working alongside him on projects like the decorations at the Palazzo Borghese. While Pietro Testa (1611-1650) was largely a contemporary who died relatively young, Lauri's long career certainly overlapped with many younger artists whom he could have influenced through his work and his position at the Academy.

His style, characterized by its elegance, narrative clarity, and often jewel-like finish in smaller works, offered a model distinct from the grand theatricality of Pietro da Cortona or the solemn classicism of his brother's teacher, Andrea Sacchi, or later classicists like Carlo Maratta (who, incidentally, succeeded Lauri as Principe of the Accademia). Lauri's focus on mythological narratives rendered with charm and precision found a ready market and likely influenced painters specializing in similar genres.

His collaborations, particularly with landscape painters like Claude Lorrain and Gaspard Dughet, also had an impact, demonstrating a successful model for integrating specialized skills. His ability to paint lively and contextually appropriate figures made him a valuable partner and set a standard for staffage painting. He operated within a rich artistic milieu that included sculptors like Bernini and Alessandro Algardi, painters covering a wide stylistic spectrum, and influential patrons, all contributing to the dynamic environment of Baroque Rome.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

Filippo Lauri remained active as an artist in Rome throughout his life. He continued to produce paintings and fulfill commissions, maintaining his reputation for quality and refinement. His long career spanned several decades of the Baroque period, witnessing stylistic shifts and the rise and fall of artistic reputations. He passed away in Rome in 1694, leaving behind a substantial body of work.

His legacy lies primarily in his skillful contribution to mythological and religious cabinet painting. His works were appreciated for their narrative charm, technical finesse, and decorative qualities. They appealed to the tastes of collectors who desired smaller, finely wrought paintings for private contemplation and enjoyment. His ability to blend Flemish precision (inherited perhaps through his father) with Italian Baroque drama and elegance resulted in a unique and attractive style.

Today, Filippo Lauri's paintings are held in numerous important museums and collections around the world, including the Palazzo Pitti in Florence, the Museo di Capodimonte in Naples, the Blanton Museum of Art in Austin, Texas, and the Royal Collection in the United Kingdom. Academic research, as evidenced by articles and catalogue entries focusing on specific works like Venus and Adonis or Chelone Transforming into a Turtle, continues to explore his iconography, technique, and place within seventeenth-century Roman art. His collaborations remain a point of interest, shedding light on artistic practices of the time.

Conclusion: A Refined Voice in the Roman Baroque

Filippo Lauri occupies a distinct and important place in the history of Italian Baroque art. While perhaps not as revolutionary as Caravaggio or as monumentally ambitious as Bernini or Cortona, he was a master craftsman with a refined sensibility and a gift for narrative. Born and trained in Rome, he absorbed the city's rich artistic traditions, from the lingering influence of Northern European landscape to the dominant currents of Baroque classicism and drama.

He excelled in creating exquisitely detailed mythological and religious scenes, often on an intimate scale, which found favour with discerning collectors. His frequent and successful collaborations with leading landscape painters like Claude Lorrain and Gaspard Dughet highlight his specialized skill in figure painting and his integration into the Roman art network. His leadership role as Principe of the Accademia di San Luca attests to the respect he commanded among his peers.

Through his elegant compositions, his mastery of detail, and his charming interpretations of classical and biblical stories, Filippo Lauri made a significant contribution to the visual culture of seventeenth-century Rome. His works continue to be admired for their beauty, technical skill, and narrative appeal, offering a window into the sophisticated tastes and artistic practices of the Baroque era.