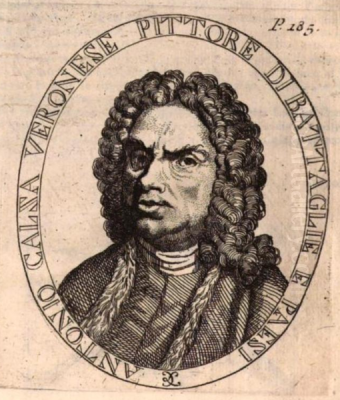

Antonio Calza stands as a significant figure in the landscape of late Italian Baroque painting. Active during a period of dramatic artistic expression and turbulent European history, Calza carved a distinct niche for himself as a specialist in battle scenes, or battaglie. Born in Verona in 1653 and passing away in the same city in 1725, his career spanned the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, witnessing the evolution of Baroque art into its later phases. He was an artist whose work captured the chaos, energy, and brutal reality of warfare with a dynamic flair that earned him considerable recognition during his lifetime and a lasting place in the annals of art history.

Calza's paintings are characterized by their vigorous compositions, dramatic use of light and shadow (chiaroscuro), and energetic brushwork. He possessed a remarkable ability to orchestrate complex scenes involving numerous figures, particularly cavalrymen and horses, locked in fierce combat. His works often convey a sense of immediacy and raw power, drawing the viewer into the heart of the conflict. While influenced by prominent predecessors and contemporaries, Calza developed a personal style that resonated with patrons seeking depictions of military prowess and historical confrontations.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Bologna

Antonio Calza's artistic journey began in his native Verona, a city with a rich artistic heritage. However, seeking formal training, he moved to Bologna, a major artistic center renowned for its influential academy and prominent painters. There, he entered the workshop of Carlo Cignani (1628–1719), a leading figure of the late Bolognese school. Cignani, known for his classical compositions and graceful figures, provided Calza with a solid foundation in drawing, composition, and the techniques of oil painting prevalent during the High Baroque period.

The artistic environment in Bologna was steeped in the legacy of masters like the Carracci family (Annibale, Agostino, and Ludovico), Guido Reni, Domenichino, and Guercino. Although Cignani represented a slightly later, more classical-leaning phase of the Bolognese tradition, the emphasis on strong draftsmanship and structured composition would have been part of Calza's early education. This initial training under Cignani likely instilled in Calza a discipline that would underpin even his most dynamic and seemingly chaotic later works.

Roman Apprenticeship and Defining Influences

A pivotal moment in Calza's development occurred when he moved to Rome. The Eternal City was the undisputed epicenter of the Baroque art world, attracting artists from across Europe. In Rome, Calza sought out the tutelage of Jacques Courtois (1621–1676), a French painter also known as 'Il Borgognone' or 'Le Bourguignon'. Courtois was arguably the most celebrated battle painter of his generation, renowned for his incredibly fluid and dynamic depictions of cavalry skirmishes and large-scale military engagements.

Studying under Courtois was transformative for Calza. He absorbed his master's techniques for rendering the swirling chaos of battle, the energetic movement of horses, and the dramatic interplay of light and shadow across the battlefield. Courtois's influence is clearly visible in Calza's subsequent focus on military subjects and his adoption of a similarly vigorous and painterly style. Calza learned to capture the essence of conflict – the confusion, the violence, and the heroism – in a way that was both visually exciting and emotionally resonant.

Beyond the direct influence of Courtois, Calza was also profoundly affected by the work of Salvator Rosa (1615–1673). Rosa, a Neapolitan painter active primarily in Rome and Florence, was known for his wild, romantic landscapes, philosophical subjects, and, significantly, his dramatic battle paintings. Rosa's battaglie often possessed a raw, almost brutal energy and a sense of untamed nature that mirrored the ferocity of human conflict. Calza drew inspiration from Rosa's dramatic compositions, his use of tenebrism (strong contrasts between light and dark), and his ability to infuse scenes with a powerful, often turbulent, atmosphere. The influence of both Courtois and Rosa shaped Calza's approach to the battaglia genre.

While in Rome, Calza would also have been exposed to the broader currents of Roman Baroque art, dominated by figures like Gian Lorenzo Bernini in sculpture and architecture, and painters such as Pietro da Cortona and Giovanni Battista Gaulli (Baciccio), known for their grand-scale illusionistic ceiling frescoes. Though Calza's focus remained on easel painting, particularly battle scenes, the overall emphasis on drama, movement, and emotional intensity characteristic of the Roman Baroque undoubtedly permeated his artistic sensibility. He also would have been aware of earlier specialists in battle scenes like Antonio Tempesta and contemporary painters exploring similar themes, such as Michelangelo Cerquozzi.

The Signature Style: Dynamics of Conflict

Antonio Calza's mature artistic style is defined by its focus on the dynamic representation of conflict. He excelled at depicting cavalry engagements, where the swirling movement of horses and riders provided ample opportunity for dramatic composition. His canvases are typically filled with action, featuring charging horses, clashing soldiers, fallen figures, and the smoke and dust of battle. He used diagonals and swirling compositional lines to enhance the sense of movement and chaos, drawing the viewer's eye across the scene.

Light plays a crucial role in Calza's work. He employed strong chiaroscuro, influenced by both Courtois and Rosa, using dramatic contrasts between brightly lit areas and deep shadows to heighten the tension and focus attention on key moments within the melee. Sunlight might break through stormy clouds or battlefield smoke, illuminating a rearing horse, a commander's gesture, or the glint of steel. This theatrical use of light adds significantly to the emotional impact of his paintings.

His brushwork is often vigorous and expressive, particularly in the rendering of figures and horses in motion. While capable of detailed passages, especially in armor or weaponry, Calza often prioritized capturing the energy of the scene over minute detail. This painterly approach contributes to the sense of immediacy and dynamism that characterizes his best work. His color palettes could be vibrant, emphasizing the colorful uniforms and banners amidst the darker tones of the landscape and smoke, further enhancing the visual drama. He displayed a particular skill in rendering horses, capturing their anatomy, power, and movement with convincing realism.

Representative Works and Thematic Focus

Antonio Calza produced a considerable body of work, primarily focused on battle scenes. Among his most representative and frequently cited works is the Battle between Christian and Turkish cavalry with castle. This painting exemplifies many of his stylistic hallmarks: a dynamic composition filled with swirling figures, dramatic lighting highlighting the central conflict, and a clear distinction between the opposing forces, often a recurring theme reflecting contemporary European conflicts with the Ottoman Empire. The inclusion of architectural elements like a castle adds depth and context to the scene.

Another notable example is the Battle of European cavalry. This title likely refers to several works depicting engagements between various European forces, a common subject during the frequent wars of the late 17th and early 18th centuries (such as the War of the Spanish Succession). These paintings showcase Calza's ability to handle large numbers of figures and create complex, multi-layered compositions that convey the scale and confusion of major battles. He often included specific details of uniforms and weaponry appropriate to the forces depicted.

Beyond these specific titles, Calza painted numerous Cavalry Skirmishes, Battle Scenes, and occasionally Siege Scenes. His thematic focus remained consistently on military engagements. These works were popular with aristocratic and military patrons who wished to commemorate victories, demonstrate power, or simply appreciate the dramatic artistry of the battaglia genre. Calza's paintings served not just as decoration but often as visual records, albeit romanticized, of the military realities of his time.

Career Trajectory, Patronage, and Personal Life

After his formative years in Bologna and Rome, Calza's career saw him active primarily in Northern Italy. He is known to have worked in various cities, adapting his skills to meet the demands of different patrons. Sources indicate that he spent time in Tuscany, possibly Florence, around 1706, shortly after marrying his first wife, mentioned as Cristine (perhaps Cristina) Coral. His movements reflect the itinerant nature of many artists of the period, who traveled to where commissions were available.

A significant connection arose through his second marriage in 1708 to Angiola Margherita Pakmann (or Pachmann). She was the daughter of Andreas Pachmann (Andreasa Pakmann), a Flemish painter. This union placed Calza within a network of artists, potentially opening doors to new opportunities and collaborations. Family connections were often crucial for professional advancement in the art world of the time.

Calza secured important commissions from prominent figures. Notably, he worked in Milan for an Austrian general referred to as Martinija. This was likely Count Georg Adam von Martinitz (or a member of his family), an Austrian diplomat and official active during that period. It is suggested that some of these works may have been connected to the celebrated military leader Prince Eugene of Savoy, one of the most powerful figures in the Habsburg Empire and a major patron of the arts. Paintings depicting military victories or scenes related to specific campaigns would have been highly sought after by such patrons. The mention of paintings commissioned by figures named "Desire and Bella" likely refers to specific, perhaps lesser-known, patrons whose identities are now obscure.

His reputation grew throughout his career, and he came to be regarded as one of the most important battle painters active after the death of his master, Jacques Courtois. His works were sought after by collectors, and his style became influential. The art historian Federico Zeri later studied Calza's work, contributing to the modern understanding and appreciation of his oeuvre, noting its presence in collections beyond Italy, including Slovenia.

Teaching, Influence, and Artistic Legacy

Antonio Calza was not only a prolific painter but also an influential teacher, passing on his expertise in the battaglia genre to the next generation. His most notable students became significant battle painters in their own right, ensuring the continuation of the style he had mastered.

Francesco Monti (1685–1768), often called 'Il Brescianino delle Battaglie' to distinguish him from another painter of the same name, studied with Calza. Monti absorbed his master's dynamic approach to battle scenes and became one of the leading specialists in the genre in Northern Italy during the first half of the 18th century. His works clearly show Calza's influence in their composition and energy.

Another important pupil was Francesco Simonini (1686–1755). Simonini worked closely with Calza and inherited his vigorous brushwork and dramatic flair. He later achieved considerable success, working for prominent patrons like Marshal Johann Matthias von der Schulenburg, a renowned military commander and art collector. Simonini's paintings represent a direct continuation and evolution of the style pioneered by Courtois and refined by Calza.

Giovanni Battista Cimaroli (1687–1771) also studied with Calza in Bologna. While Cimaroli eventually became better known as a landscape painter (pittore di vedute), particularly active in Venice where he sometimes collaborated with Canaletto by painting the figures in his views, his early training under Calza likely influenced his handling of figures and composition. Furthermore, Cimaroli married Calza's sister-in-law, Giovanna Caterina Pachman, further strengthening the artistic and familial ties between them.

Calza's influence extended indirectly as well. The English painter Thomas Bardwell (1704–1767) is said to have studied with an artist named Antonio Aureggio, who himself had reportedly been influenced by Calza while studying in Bologna. While such connections can be tenuous, they suggest the ripple effect of Calza's reputation and teaching. His style, rooted in the dramatic realism of Courtois and Rosa, provided a powerful model for depicting conflict that resonated with artists and patrons alike throughout the late Baroque and early Rococo periods.

Later Years and Enduring Significance

Antonio Calza eventually returned to his native Verona, where he died on April 18, 1725. He left behind a substantial body of work that cemented his reputation as a leading master of the battle painting genre. While perhaps overshadowed in broader art historical narratives by artists with a wider thematic range, within his chosen specialization, Calza holds a significant position.

His primary contribution lies in his skillful synthesis of the influences of Jacques Courtois and Salvator Rosa, creating dynamic, atmospheric, and emotionally charged depictions of warfare. He captured the visceral energy of combat, particularly cavalry engagements, with a consistency and flair that few contemporaries could match. His paintings offer a window into the military conflicts of his era, filtered through the dramatic lens of the late Baroque aesthetic.

Calza's importance is also evident in his role as a teacher. Through pupils like Francesco Monti and Francesco Simonini, his approach to battle painting continued to influence Italian art well into the 18th century. His work remains represented in various European museums and private collections, appreciated for its technical skill, compositional energy, and powerful evocation of the drama of battle. Antonio Calza remains a key figure for understanding the evolution of the battaglia genre and the artistic landscape of Northern Italy during the transition from the High Baroque to the Rococo.