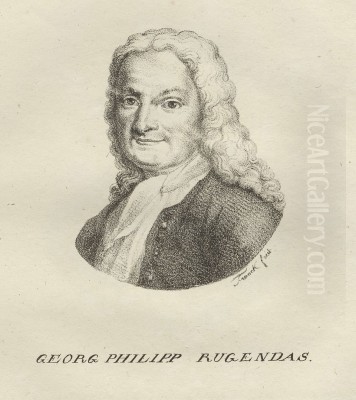

Georg Philipp Rugendas the Elder stands as a significant figure in German Baroque art, renowned primarily for his dynamic and often gritty depictions of battle scenes. Born in the Free Imperial City of Augsburg in 1666 and passing away there in 1742, Rugendas carved a niche for himself as both a painter and a highly skilled engraver, particularly mastering the mezzotint technique. His life spanned a period of significant political and military upheaval in Europe, events that provided the dramatic subject matter for which he became famous. His work not only captured the chaos and energy of warfare but also served as historical documentation, influencing artists and patrons far beyond the borders of his native Augsburg.

Formative Years and Artistic Development

Georg Philipp Rugendas was born into an artistic environment in Augsburg, a city celebrated for its goldsmiths, printers, and painters. His initial artistic training came from his father, who was himself an engraver, providing the young Georg Philipp with a foundational understanding of line, form, and the meticulous processes involved in printmaking. This early exposure to engraving would prove crucial throughout his career, complementing his work in painting and drawing.

Seeking to broaden his artistic horizons, Rugendas embarked on travels that were essential for ambitious artists of his time. He journeyed to Italy, spending time in Venice and Rome between 1690 and 1692. Rome, the vibrant heart of the Baroque, offered exposure to the works of Italian masters and the dynamic compositions that characterized the era. He likely studied the works of artists known for dramatic narratives and energetic figures. Encounters with the works of battle painters like Jacques Courtois, known as 'Il Borgognone', or the dramatic landscapes and scenes of Salvator Rosa may have further solidified his interest in dynamic and tumultuous subjects.

His travels also took him to Vienna, the capital of the Habsburg Empire. This city, frequently on the front lines or dealing with the aftermath of conflicts with the Ottoman Empire, provided further exposure to military life and the visual culture surrounding warfare. These experiences abroad honed his skills, refined his style, and provided him with a wealth of visual information that he would draw upon throughout his career upon returning to Augsburg around 1693.

The Eye of the Storm: Style and Subject Matter

Rugendas the Elder's artistic identity is inextricably linked to his depictions of battle. He specialized in capturing the frenetic energy, chaos, and violence of cavalry skirmishes, sieges, and military encampments. His approach was rooted in realism, striving for accuracy in the depiction of uniforms, weaponry, and the tumultuous movements of men and horses in combat. Horses, in particular, were a recurring and masterfully rendered element in his work, captured in moments of rearing, charging, or falling amidst the fray.

His style embodies the dynamism of the High Baroque. Compositions are often complex, filled with swirling masses of figures, dramatic contrasts of light and shadow (chiaroscuro), and a palpable sense of movement. He worked proficiently across various media. His oil paintings allowed for rich colour and texture, suitable for large-scale commissions. His drawings and sketches often served as preparatory studies, capturing immediate observations with vigour.

Furthermore, Rugendas was a master engraver, particularly noted for his skill in mezzotint. This technique, which allows for the creation of tonal areas rather than just lines, was perfectly suited to reproducing the painterly effects of light and shadow found in his drawings and paintings. His engravings played a crucial role in disseminating his compositions to a wider audience, enhancing his reputation throughout Europe. The violence inherent in his subjects was depicted unflinchingly, contributing to the dramatic impact but also occasionally drawing comment for its graphic nature.

Witness to History: The Siege of Augsburg

One of Rugendas's most significant early contributions involved documenting a major historical event he personally witnessed: the Siege of Augsburg during the War of the Spanish Succession. In the winter of 1703-1704, the city was besieged and ultimately captured by Bavarian and French forces. Rugendas, present in the city, observed the military actions firsthand.

This direct experience provided the basis for a powerful series of engravings depicting various aspects of the siege. These prints were not romanticized visions of war but rather detailed, journalistic accounts of the events, showcasing troop movements, artillery bombardments, and the city's defenses under pressure. The immediacy derived from his personal observation lent these works a particular authority and impact. This series cemented his reputation as a skilled battle artist capable of capturing the realities of contemporary warfare, moving beyond generic historical or mythological battles.

Patronage and Major Canvases

Rugendas's skill attracted high-profile patrons. Among his most important commissions were four large-scale battle paintings created between 1708 and 1709 for Lothar Franz von Schönborn, the influential Elector-Archbishop of Mainz and Prince-Bishop of Bamberg. These works were destined for Schloss Gaibach. One of the most celebrated paintings from this series is the Great Cavalry Battle – Fight for the Flag. This canvas exemplifies Rugendas's style, depicting a chaotic clash, likely representing Habsburg imperial forces against Ottoman adversaries, a common theme reflecting ongoing conflicts in Eastern Europe. The dynamic composition, swirling figures, and focus on the struggle for the standard showcase his ability to handle complex, multi-figure scenes with dramatic flair.

Later works continued to explore similar themes. A painting like Cavalry Battle in an Open Landscape, dated 1738, demonstrates his enduring commitment to the genre throughout his career. It features his characteristic energetic portrayal of horses and riders engaged in fierce combat, set against a broad landscape that provides context and depth. Another known work is the oil painting Reitschawl (likely meaning a cavalry review or skirmish), a smaller piece measuring 51.5 x 63.1 cm, which found its home in the collection of the Wallraf-Richartz Museum in Cologne, indicating the reach of his work beyond Augsburg.

Leadership in Augsburg's Art Scene

Beyond his personal artistic practice, Georg Philipp Rugendas the Elder played a significant role in the institutional art life of Augsburg. In 1710, he was appointed the director and professor of the newly founded Imperial Academy of Fine Arts (Reichsstädtische Kunstakademie) in Augsburg. This position underscored his standing within the city's artistic community and gave him a platform to influence the next generation of artists. The Academy aimed to provide structured training and uphold artistic standards in the city.

His civic standing was further recognized in 1727 when he became a member of Augsburg's Great Council (Großer Rat). This involvement in civic governance indicates a level of respect and influence that extended beyond purely artistic circles. His leadership at the Academy placed him alongside other notable Augsburg artists of the period, such as the painter Johann Georg Bergmüller, who was also associated with the institution and known for his frescoes and altarpieces. Rugendas's roles solidified his position as a leading figure in Augsburg's cultural landscape during the first half of the 18th century.

A Family Affair: The Rugendas Workshop

Artistic skill often ran in families during this period, and the Rugendas were no exception. Georg Philipp the Elder worked closely with his sons, who followed him into the artistic profession. Two sons, in particular, are noted for their collaboration: Christian Rugendas (1708–1781) and Georg Philipp Rugendas the Younger (1701–1774). They often assisted their father, particularly in the demanding work of engraving and publishing prints based on his designs.

Christian Rugendas, especially, became known for continuing his father's legacy after his death in 1742. He published numerous prints based on his father's drawings and paintings. However, this practice sometimes attracted criticism. Some contemporaries noted that Christian's prints often directly replicated his father's work without significant original contribution or interpretation. This led to discussions about originality and artistic merit. Interestingly, Christian himself seems to have been quite open about this, acknowledging the source of his work with a degree of frankness that some found disarming, if not entirely artistically ambitious. Despite these debates, the family workshop ensured the continued dissemination and popularity of Georg Philipp Rugendas the Elder's distinctive battle scenes.

Cross-Cultural Echoes: Influence in Imperial China

One of the most fascinating aspects of Rugendas's legacy is the unexpected influence his work exerted in Qing Dynasty China. The Qianlong Emperor (reigned 1735–1796), a great patron of the arts, admired European depictions of battles, particularly for their realism and dynamism, which contrasted with traditional Chinese styles. He sought to commemorate his own military victories in a similar manner.

Through the Jesuit missionaries serving at the imperial court in Beijing, notably the Italian painter Giuseppe Castiglione (known in China as Lang Shining), the Emperor became aware of European battle art. Rugendas's engravings, known for their detailed and dramatic portrayal of cavalry combat, were among the European works that caught the Emperor's attention and served as stylistic models.

The Emperor commissioned a series of large paintings depicting his military campaigns, executed by court artists including Castiglione, Jean-Denis Attiret, Ignatius Sichelbart, and Giovanni Damasceno Sallusti. To have these monumental paintings translated into engravings for wider distribution, the Qianlong Emperor took the unusual step of sending reduced copies of the paintings to Europe. They were sent to Paris, a major center for printmaking, where renowned French engravers, possibly including figures like Charles-Nicolas Cochin the Younger, were employed to create copperplate engravings based on the designs originating from the Beijing court but influenced by European styles like that of Rugendas. The finished copperplates were then sent back to China, where the final printing took place, often involving Jesuit-trained Chinese artisans. This complex, cross-cultural project highlights the global reach of European artistic styles in the 18th century and the specific appeal of Rugendas's dynamic battle imagery.

Contemporaries and Artistic Milieu

Georg Philipp Rugendas the Elder operated within a rich artistic context, both locally in Augsburg and internationally. His direct collaborators included his father (his first teacher) and his sons, Christian Rugendas and Georg Philipp Rugendas the Younger. His major patron, Lothar Franz von Schönborn, connects him to the highest levels of ecclesiastical and aristocratic patronage in the Holy Roman Empire.

His influence reached Emperor Qianlong in China, a project involving court painters like Giuseppe Castiglione (Lang Shining) and likely Parisian engravers such as Charles-Nicolas Cochin the Younger. Within Augsburg, he was a contemporary of artists like Johann Georg Bergmüller, a fellow figure at the Academy, and worked in a city whose artistic heritage included masters like Hans Holbein the Elder, Hans Burgkmair, and later figures whose works might be found in local collections, such as Bernhard Strigel, Lucas Cranach the Elder, and Hans Baldung Grien. The Augsburg Art Cabinet, created by Philipp Hainhofer earlier in the 17th century, exemplifies the city's tradition of intricate craftsmanship and collecting.

While direct interactions are not always documented, Rugendas would have been aware of other European artists specializing in similar genres. The aforementioned Jacques Courtois (Il Borgognone) and Salvator Rosa were prominent Italian predecessors in battle and dramatic landscape painting. The works collected by figures like Prince Nikolaus Esterházy (whose collection later formed the core of the Budapest Museum of Fine Arts) show the broader taste of the era, including artists like Claude Lorrain, Nicolas Poussin, Paolo Veronese (Caliari), and portraits by artists like Joseph Lanzedelly. Rugendas's work fits firmly within this Baroque landscape, contributing a distinct German perspective focused on the visceral reality of conflict.

Legacy and Collections

Georg Philipp Rugendas the Elder left a lasting legacy as one of the foremost German painters and engravers of battle scenes in the Baroque era. His ability to combine detailed realism with dramatic energy made his work highly sought after during his lifetime and ensured its continued relevance. His engravings, in particular, allowed for wide circulation, spreading his compositions and style across Europe and even, remarkably, influencing art commissioned by the Chinese Emperor.

His role as the founding director of the Augsburg Academy of Art highlights his importance to the artistic life of his native city. He not only produced a significant body of work but also contributed to the training of future artists. The Rugendas family workshop, continued by his sons, further cemented the family name's association with military art.

Today, works by Georg Philipp Rugendas the Elder are held in numerous public collections. In Augsburg, his works can be found in the city's art collections (Städtische Kunstsammlungen), particularly within the holdings of the Grafisches Kabinett (print room) and potentially displayed at the Schaezlerpalais. The significant group of paintings commissioned by Lothar Franz von Schönborn originally for Schloss Gaibach has partly found its way into the Staatsgalerie Stuttgart. The Esterházy collection, which included works by Rugendas, forms a major part of the Museum of Fine Arts in Budapest. The Wallraf-Richartz Museum in Cologne holds his painting Reitschawl. Numerous prints and drawings are also housed in major print rooms worldwide, attesting to his proficiency and influence as a graphic artist.

Conclusion

Georg Philipp Rugendas the Elder remains a key figure in the study of German Baroque art. His specialization in battle painting and engraving provided a vivid and often unsparing look at the military conflicts of his time. Combining meticulous observation, particularly evident in his Siege of Augsburg series, with the dynamic compositions and dramatic flair characteristic of the Baroque, he created powerful images of warfare. His leadership in Augsburg's art scene, his collaborations within his family workshop, and the surprising reach of his influence to Imperial China underscore his significance. Rugendas masterfully chronicled the turbulence of his era, leaving behind a body of work valued for both its artistic merit and its historical insight.