Artur Nikodem stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in early 20th-century Austrian art, particularly within the vibrant artistic landscape of Tyrol. His life and work offer a fascinating study of an artist deeply rooted in his alpine environment, yet responsive to broader European artistic currents and profoundly affected by the political upheavals of his time. From his early academic training to his mature explorations of landscape and portraiture, and through the challenging years of National Socialism, Nikodem forged a distinctive artistic path.

Early Life and Artistic Inclinations

Born on February 6, 1870, in Trento, Italy—then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire—Artur Nikodem's artistic journey began with a divergence from his parents' initial aspirations for his education. While they envisioned him attending the prestigious Brera Academy in Milan, Nikodem, driven by his own artistic compass, chose instead to enroll at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich around 1888. This decision placed him in one of the leading art centers of German-speaking Europe, a city buzzing with new ideas and a burgeoning Secessionist spirit that challenged academic conservatism.

Munich at this time was a crucible of artistic innovation. Artists like Franz von Stuck, Lovis Corinth, and Max Slevogt were active, pushing the boundaries of traditional painting. While Nikodem's direct tutelage under specific masters there isn't extensively detailed in all records, the atmosphere of the Munich Academy, with its emphasis on strong draftsmanship and an engagement with both realism and emerging Symbolist and Jugendstil tendencies, would undoubtedly have shaped his formative artistic understanding. He was exposed to a rich tapestry of influences, from the lingering traditions of 19th-century naturalism to the fresh winds of modernism.

Formative Experiences: Naval Service and Early Travels

Nikodem's formal artistic studies were interrupted in 1889 when he joined the German Navy. This period, though brief, was significant, offering him exposure to different cultures and landscapes. His naval service included participation in military actions that took him to Egypt and Asia Minor. These travels provided him with a wealth of visual experiences far removed from the Alpine scenery of his youth or the academic halls of Munich. The vibrant colors, exotic architectures, and distinct light of the Near East would later find echoes in some of his works, particularly those with an Orientalist flavor.

However, his naval career was short-lived. In 1890, for personal reasons, he secured a discharge from the military and returned to Trento, where his parents resided. This return marked a period of transition. In 1891, he began working at the local post office, a practical necessity that perhaps provided a stable, if unartistic, counterpoint to his creative ambitions. This phase of his life, balancing mundane work with artistic development, is common for many artists at the outset of their careers.

The Merano Period: Cultivating an Artistic Identity

A pivotal move occurred in 1893 when Nikodem relocated to Merano (Meran), a spa town in South Tyrol known for its mild climate and cosmopolitan atmosphere, which also attracted artists and intellectuals. It was in Merano that his artistic career truly began to blossom. He became an active member of the "Meraner Künstlerbund" (Merano Artists' Association), a crucial step for any aspiring artist seeking community, exhibition opportunities, and critical engagement.

The Künstlerbund provided a platform for Nikodem to regularly exhibit his works, allowing him to gain visibility and refine his style in dialogue with his peers and the public. His paintings from this period likely began to show the emerging characteristics of his mature style: a strong connection to the Tyrolean landscape, an interest in portraiture, and an evolving approach to color and form influenced by his Munich training and personal observations. Artists like Albin Egger-Lienz, though perhaps more monumental in his peasant scenes, was another dominant figure in Tyrolean art, and the regional artistic environment would have been one of shared concerns for depicting local identity and landscape.

Innsbruck and the Maturation of Style

In 1908, Artur Nikodem, along with his family, moved to Innsbruck, the capital of Tyrol. This city would become his home for the remainder of his life and the backdrop against which his artistic career reached its zenith. Innsbruck, nestled in the heart of the Alps, offered him endless inspiration for his landscape painting, which became a cornerstone of his oeuvre.

His style continued to evolve, drawing from the rich tradition of Tyrolean landscape painting but infusing it with a modern sensibility. He was not a mere documentarian of scenic views; rather, he sought to capture the mood, the light, and the inherent monumentality of the Alpine world. His landscapes often feature bold compositions, a vibrant palette, and a simplification of forms that lends them a powerful, almost symbolic quality. He shared this deep connection to the Alpine landscape with other Tyrolean artists such as Alfons Walde, known for his iconic depictions of skiers and mountain villages, and Rudolf Wackerle, who also focused on Tyrolean life and scenery.

Alongside landscapes, Nikodem was a gifted portraitist, with a particular focus on female subjects. His portraits are characterized by a sensitive psychological insight and an elegant rendering of form and fabric. He often imbued his female figures with an air of mystery or quiet contemplation, moving beyond mere likeness to explore character and mood.

The First World War and Orientalist Echoes

The outbreak of the First World War in 1914 inevitably impacted Nikodem's life and art. He was called to service, and his duties eventually took him to Bulgaria and Turkey. He spent a significant period stationed in Constantinople (now Istanbul). This renewed exposure to the East, building on his earlier naval travels, had a discernible effect on his work.

During and immediately after this period, Nikodem produced a series of paintings with distinctly Orientalist themes. These works, often characterized by rich colors, exotic settings, and depictions of local figures, such as his Arab Woman (1916), showcase his fascination with the cultures he encountered. This engagement with Orientalism was part of a broader European artistic trend, but Nikodem brought his own observational skills and stylistic tendencies to the genre. These pieces add another layer to his diverse body of work, demonstrating his versatility and his ability to absorb and reinterpret new visual stimuli.

After the war, in 1918, he returned to his family in Innsbruck (though some sources mention a brief return to Trento and work at the post office again in 1919 before settling definitively in Innsbruck). The post-war period was one of significant artistic activity and recognition for him.

The Interwar Years: Peak Productivity and Recognition

The 1920s marked a period of intense creativity and considerable success for Artur Nikodem. He became one of the most respected and sought-after artists in Tyrol. His work was widely exhibited, and he gained a reputation for his mastery of both landscape and portraiture.

Several of his most iconic works date from this era. Starry Sky (1923) is a captivating nocturnal scene, where Nikodem uses deep blues and whites to evoke the silent majesty of the night sky over the mountains. Sunflower Tree (1921) demonstrates his ability to find monumental beauty in natural forms, transforming a simple subject into a vibrant expression of life. Tyrolean Forest in the Wind (1922) captures the dynamic energy of nature, while Shepherd (1926) reflects his continued engagement with traditional Tyrolean life.

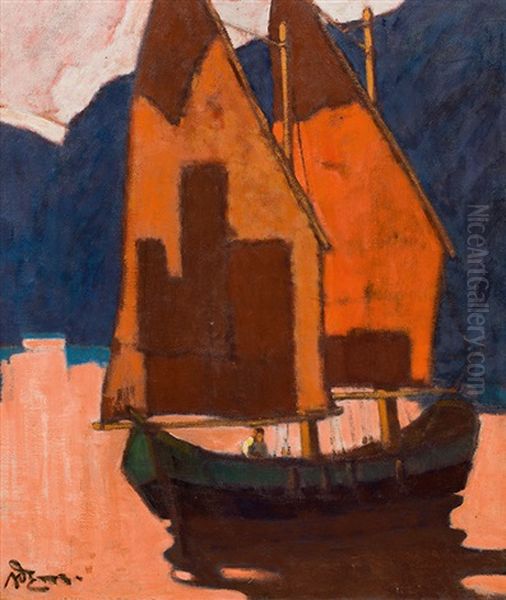

His portraiture also flourished. Portrait (1926) and Woman Without a Shadow (1926) are exemplary of his skill in capturing not just the likeness but also the inner world of his sitters. These works often display a sophisticated use of color and a subtle interplay of light and shadow, creating a sense of depth and presence. Other notable works from this period and slightly later include Golden Horn (after 1926), Stams in Tyrol (c. 1930), Autumn Landscape (1936), Sailing Boat (1919-1920), and Entry into the Maltatal (109). Tree in Morning Light (1922) is another example of his sensitive landscape work.

Nikodem's style during these years can be seen as aligning with certain aspects of the broader European movement known as New Objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit). This movement, which emerged as a reaction against the emotionalism of Expressionism, favored a more sober, realistic, and often sharply focused depiction of the world. While Nikodem's work lacked the biting social critique of German New Objectivity artists like Otto Dix or George Grosz, his clear forms, precise rendering, and objective yet empathetic approach to his subjects resonate with the Austrian variant of this trend, which often had a more lyrical or regionally focused character, as seen in the works of artists like Rudolf Wacker or Herbert Boeckl.

He participated in important exhibitions, including the "Tyrolean Artists" exhibition held in Germany in 1925-1926, which aimed to showcase the unique artistic contributions of the region. This aligns with the efforts of artists like Albin Egger-Lienz, who also championed a distinct Tyrolean artistic identity.

Artistic Affiliations and the Tyrolean Context

Artur Nikodem was deeply embedded in the Tyrolean art scene. His association with the Meraner Künstlerbund early in his career was foundational. Later, in Innsbruck, he was part of a community of artists who, while diverse in their individual styles, shared a common ground in their depiction of the Tyrolean landscape, its people, and its culture.

His contemporaries in Tyrol included the aforementioned Albin Egger-Lienz, whose monumental depictions of peasant life and war had a profound impact on Austrian art. Alfons Walde, with his distinctive, brightly colored paintings of Tyrolean winter scenes and robust figures, became an iconic portrayer of the region. Ernst Nepo, another significant Tyrolean artist associated with New Objectivity, explored themes of local life and portraiture with a clear, often stark, realism. Rudolf Wackerle, primarily a sculptor but also a painter, contributed to the regional artistic discourse.

While Nikodem's style was his own, he shared with these artists a commitment to representing their homeland, albeit through different artistic lenses. The influence of the Munich Secession, with figures like Max Liebermann or Lovis Corinth, and even broader European trends like Post-Impressionism or the work of Alpine painters such as Giovanni Segantini or Ferdinand Hodler (though Swiss), formed part of the artistic atmosphere that shaped Tyrolean modernism. The legacy of earlier Austrian masters like Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele, who had revolutionized Austrian art a generation before, also created a fertile ground for subsequent modernist explorations, even if their styles were markedly different from Nikodem's. Oskar Kokoschka, another major Austrian Expressionist, was also a contemporary force.

The Shadow of National Socialism: "Degenerate Art" and Seclusion

The rise of National Socialism in Germany and its eventual annexation of Austria (the Anschluss) in 1938 cast a dark shadow over Artur Nikodem's later career. The Nazi regime had a rigid and oppressive cultural policy, promoting a narrow vision of "Germanic" art and denouncing modern art movements as "degenerate" (Entartete Kunst). Artists whose work did not conform to Nazi ideals, or who were deemed politically or racially undesirable, faced persecution, prohibition from working or exhibiting, and confiscation of their art.

Artur Nikodem's work, with its modern sensibilities and perhaps its departure from the heroic, idealized imagery favored by the Nazis, was classified as "degenerate." This had devastating consequences for him. He was effectively banned from publicly exhibiting his paintings and was forced into a period of internal exile and seclusion. This was a fate shared by many leading modern artists across Germany and Austria, including Emil Nolde, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, and Paul Klee, whose works were famously pilloried in the "Degenerate Art" exhibition of 1937.

During these difficult years, Nikodem continued to paint in private, but the vibrant public career he had enjoyed was abruptly curtailed. His output in this late period is said to have included many smaller-format works, often in black and white, perhaps reflecting the somber mood and constrained circumstances. This enforced isolation was a tragic turn for an artist who had been at the forefront of Tyrolean art.

Later Years, Death, and Legacy

Artur Nikodem lived out his final years in Innsbruck under the shadow of the Nazi regime. He passed away on February 7, 1940, just a day after his 70th birthday. The vibrant artistic life he had known had been silenced by political oppression, and his death occurred at a time when his art could not be openly celebrated.

Despite the suppression during the Nazi era, Nikodem's artistic contributions were too significant to remain forgotten. After the Second World War, as Austria began to rebuild and re-evaluate its cultural heritage, there was a renewed interest in artists whose careers had been unjustly interrupted. Nikodem's work gradually regained recognition. Posthumous exhibitions, such as one noted at the Innsbruck Antiques Fair in 1988, and more recent showcases, including a 2023 exhibition that featured some of his important pieces, have helped to re-establish his reputation.

Today, Artur Nikodem is recognized as a key figure in Tyrolean modernism. His paintings are valued for their technical skill, their evocative portrayal of the Alpine landscape, their sensitive rendering of human subjects, and their unique synthesis of traditional Tyrolean themes with modern artistic approaches. His ability to navigate different influences—from Munich academicism to Orientalism and the currents of New Objectivity—while maintaining a distinct personal vision, marks him as an artist of substance.

His oeuvre reflects not only the beauty of his native Tyrol but also the complex artistic and political currents of the first half of the 20th century. His landscapes convey a deep love for the mountains, while his portraits reveal a keen understanding of human psychology. The interruption of his career by the Nazis is a poignant reminder of the fragility of artistic freedom in times of political extremism.

Conclusion: An Enduring Tyrolean Voice

Artur Nikodem's artistic journey was one of dedication, adaptation, and resilience. From his early defiance of familial expectations to pursue art in Munich, through his formative experiences in the navy and his flourishing career in Merano and Innsbruck, he consistently sought to express his unique vision. His engagement with the Tyrolean landscape was profound, resulting in works that are both regionally specific and universally appealing in their depiction of nature's grandeur.

His portraits, especially of women, demonstrate a nuanced sensitivity. The influence of his travels, particularly to the East, added an exotic dimension to his work, showcasing his versatility. While the "degenerate art" label cast a pall over his final years, his legacy endures. Artur Nikodem remains an important representative of Austrian modernism, a painter whose works continue to resonate with their blend of traditional rootedness and modern sensibility, securing his place in the annals of Tyrolean and Austrian art history. His life and art serve as a testament to the enduring power of creativity in the face of adversity.