Paul Klee stands as one of the most inventive and influential figures in twentieth-century art. A Swiss-born German artist, his highly individual style navigated the currents of Expressionism, Cubism, and Surrealism, yet ultimately transcended easy categorization. Klee was a natural draftsman who experimented relentlessly with color theory, eventually developing a deeply personal language of signs and symbols. His work, often small in scale but vast in imaginative scope, explores the realms of fantasy, music, poetry, and the natural world. As a dedicated teacher at the Bauhaus and a profound thinker about art, Klee left behind not only nearly 10,000 artworks but also significant theoretical writings that continue to inspire artists and designers today.

Early Life and Musical Roots

Paul Klee was born on December 18, 1879, in Münchenbuchsee, near Bern, Switzerland. His background was steeped in music; his German father, Hans Wilhelm Klee, was a music teacher at the Bern State Seminary, and his Swiss mother, Ida Marie Klee (née Frick), was a trained professional singer. Young Paul showed considerable talent in both music and visual art. He began playing the violin at age seven and became so proficient that, by eleven, he was invited to play as an extraordinary member of the Bern Music Association orchestra. Music would remain a lifelong passion and a profound influence on his artistic thinking.

Despite his musical gifts and his parents' inclinations, Klee felt drawn more strongly towards the visual arts, perhaps seeing it as a field less bound by tradition and offering greater potential for modern innovation. He filled notebooks with landscape sketches and caricatures from an early age. His childhood drawings, often displaying a precocious skill and wit, were something he valued throughout his life, seeing in them an uncorrupted creative impulse. This early immersion in both music and drawing laid the foundation for his later explorations of rhythm, harmony, and counterpoint in visual terms.

Artistic Formation in Munich and Italy

In 1898, after much deliberation and against his parents' initial preference for a musical career, Klee moved to Munich to study art. Munich was then a major European art center. He initially studied graphics with Heinrich Knirr before gaining admission to the Munich Academy of Fine Arts in 1900. There, he studied under Franz von Stuck, a prominent symbolist painter known for his mythological themes and Jugendstil (Art Nouveau) leanings. Klee, however, found the academic atmosphere stifling and Stuck's traditional approach less than inspiring for his burgeoning modern sensibilities.

A crucial formative experience was his journey to Italy from 1901 to 1902, undertaken with his friend, the sculptor Hermann Haller. Traveling through Genoa, Florence, Rome, and Naples, Klee absorbed the masterpieces of the Italian Renaissance, the early Christian art of Ravenna with its stunning mosaics, and the classical art of antiquity. While impressed by the masters, he felt a certain distance from their world, solidifying his resolve to find his own path. Upon returning, he spent several years back in Bern, developing his skills independently, focusing primarily on etchings, including the satirical and grotesque series titled Inventions (1903-1905).

In 1906, Klee married the Bavarian pianist Lily Stumpf, whom he had met during his student years. They settled in Munich, and their only child, Felix Paul Klee, was born the following year. During these early Munich years, Klee worked somewhat in isolation, though he exhibited occasionally. Lily provided the main financial support through her piano teaching and performances, while Paul managed the household and dedicated himself to his art, gradually developing his unique graphic style.

Finding a Voice: Color and the Avant-Garde

For much of his early career, Klee worked primarily in monochrome, excelling as a draftsman but struggling to master color. He felt his grasp of color was inadequate, a deficiency he consciously sought to overcome. His encounter with the avant-garde movements bubbling in Munich proved pivotal. Around 1911, he established connections with the artists associated with Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider), a key group within German Expressionism. He developed important friendships with Wassily Kandinsky, Franz Marc, and August Macke.

Klee participated in the second Blue Rider exhibition in 1912, which focused on graphic arts. He was deeply impressed by the color experiments of Kandinsky and Marc, as well as the Orphism of the French painter Robert Delaunay, whose essay "On Light" Klee translated for the avant-garde journal Der Sturm. These encounters stimulated his own thinking about color's expressive and structural possibilities. He began incorporating more color into his watercolors and experimenting with abstract compositions.

The true breakthrough in Klee's relationship with color occurred during a trip to Tunisia in April 1914 with fellow artists August Macke and Louis Moilliet. The intense light and vibrant colors of North Africa had a profound impact. In his diary, Klee famously declared from Kairouan: "Color has taken possession of me; no longer do I have to chase after it, I know that it has hold of me forever... Color and I are one. I am a painter." This journey liberated his palette and integrated color fully into his artistic vision, moving him decisively towards abstraction.

Association with Der Blaue Reiter

Klee's involvement with the Blue Rider group, although perhaps less central than that of Kandinsky or Marc, was significant for his development and integration into the modernist scene. He shared their spiritual aspirations for art and their interest in non-Western art, folk art, and children's drawings as sources of authentic expression. The group's almanac and exhibitions provided a platform for diverse artistic approaches united by a desire to move beyond surface appearances and express inner truths.

Klee contributed graphics to the second Blue Rider exhibition in 1912, held at the Galerie Goltz in Munich. His intricate, often whimsical line drawings found a receptive audience within this circle that valued spiritual and symbolic content. His friendship with Kandinsky, initiated during this period, would become one of the most important artistic dialogues of his life, continuing through their years together at the Bauhaus and beyond. The Blue Rider's embrace of abstraction and expressive color confirmed Klee's own artistic direction.

Although the Blue Rider group itself was short-lived, dissolving with the outbreak of World War I (which claimed the lives of both Marc and Macke), its spirit profoundly shaped Klee's path. It connected him to the forefront of European modernism and reinforced his commitment to an art that synthesized the spiritual and the formal, the intuitive and the intellectual.

The Bauhaus Years: Teacher and Theorist

In 1920, Walter Gropius, founder of the influential Bauhaus school of art, design, and architecture, invited Klee to join the faculty. Klee accepted and began teaching in Weimar in 1921, later moving with the school to Dessau in 1926. He remained a central figure at the Bauhaus until 1931. His role involved teaching workshops (initially bookbinding, later stained glass and mural painting) and, most importantly, lecturing extensively on pictorial form and design theory.

At the Bauhaus, Klee worked alongside an extraordinary group of artists, including Wassily Kandinsky (who joined in 1922), Lyonel Feininger, Oskar Schlemmer, László Moholy-Nagy, and Josef Albers. The environment fostered intense exchange and experimentation. Klee's teaching was highly methodical yet deeply intuitive. He developed complex theories about the dynamic genesis of form, starting from the point, moving to the line, plane, and space, often using analogies from nature and music.

His lectures, meticulously prepared with diagrams and notes, formed the basis for his theoretical writings. In 1925, the Bauhaus published his Pädagogisches Skizzenbuch (Pedagogical Sketchbook), a concise distillation of his core ideas on form production. His extensive lecture notes were later compiled and published posthumously as Das bildnerische Denken (The Thinking Eye) and Unendliche Naturgeschichte (The Nature of Nature), solidifying his reputation as a major art theorist of the 20th century.

The Blue Four

While teaching at the Bauhaus, Klee, along with Kandinsky, Feininger, and the Russian Expressionist Alexei Jawlensky (who was not at the Bauhaus but shared similar artistic aims), formed the group Die Blaue Vier (The Blue Four) in 1924. This alliance was initiated by the art dealer Galka Scheyer, who aimed to promote their work internationally, particularly in the United States.

Scheyer organized numerous exhibitions and lectures featuring the Blue Four across America throughout the 1920s and 1930s. The name deliberately echoed the earlier Blue Rider group, signaling a continuity of spiritual and abstract concerns in art. While the four artists maintained distinct styles, they were presented as united by their commitment to modernism and their roles as leading figures of the European avant-garde. The Blue Four helped establish Klee's international reputation and introduced his unique art to a wider audience beyond Germany.

Klee's Unique Artistic Language

Paul Klee's art is characterized by its synthesis of apparent opposites: calculation and intuition, abstraction and figuration, humor and profundity, the microscopic and the cosmic. He famously described his process with the phrase "taking a line for a walk," suggesting a journey of discovery where the line itself seems to generate form and meaning. His draftsmanship remained central; intricate, sensitive lines define contours, create textures, and weave complex narratives within his compositions.

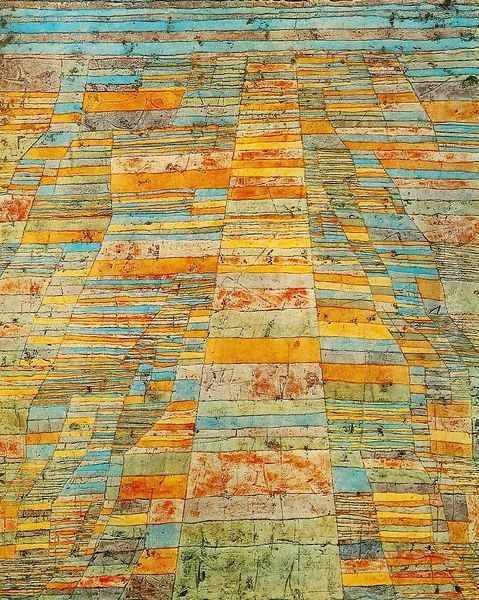

Color in Klee's work is rarely purely descriptive. Instead, it functions structurally, emotionally, and symbolically. Influenced by Delaunay's Orphism and his own Tunisian experience, he explored color harmonies and dissonances, often using grids or mosaic-like patches of color (as in Ad Parnassum) to build his compositions. He experimented widely with media, mixing watercolor, oil, ink, pastel, and tempera, often on unconventional supports like burlap, cardboard, or specially prepared grounds, achieving unique textural effects.

His works often incorporate signs, arrows, letters, numbers, or hieroglyph-like symbols, creating a visual poetry that invites interpretation but resists simple decoding. Themes range from landscapes and cityscapes (often transformed into dreamlike visions) to portraits, animals, plants, mythological figures, and purely abstract constructions. A sense of gentle irony, whimsy, and childlike wonder pervades much of his oeuvre, coexisting with deeper explorations of life, death, and the human condition. Klee meticulously cataloged almost all his works, assigning each a number and often a poetic or evocative title, creating a comprehensive record of his artistic journey.

Exploring Key Themes and Works

Klee's vast output includes numerous works that have become icons of modern art. Twittering Machine (1922), a delicate oil transfer drawing with watercolor, depicts a fragile contraption of bird-like figures on a crank. It evokes sound, movement, and mechanism with a characteristic blend of humor and menace, suggesting the precarious relationship between nature and technology.

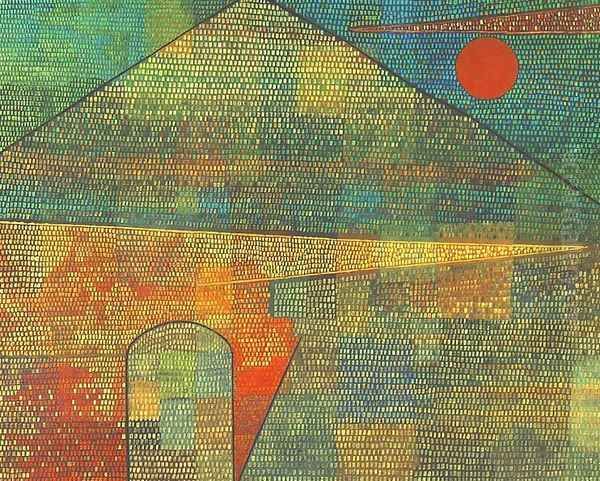

Ad Parnassum (1932), one of his largest and most complex paintings, exemplifies his mastery of color and pointillist technique. Built from thousands of tiny, individually painted squares of color, it creates a shimmering, mosaic-like surface depicting an abstracted pyramid or mountain structure beneath a celestial body. The title references Mount Parnassus, home of the Muses in Greek mythology, suggesting an ascent towards artistic or spiritual enlightenment.

Angelus Novus (New Angel) (1920), a monoprint Klee colored with watercolor, became famous through its ownership by the philosopher Walter Benjamin, who interpreted it as the "angel of history," facing the past's wreckage while being blown backwards into the future by the storm of progress. The wide-eyed, ambiguous figure captures a sense of awe and apprehension that resonates with historical trauma.

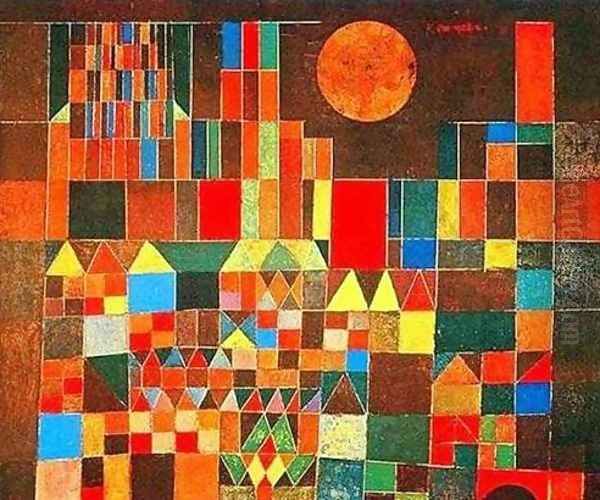

Castle and Sun (1928) showcases Klee's use of geometric shapes and warm, harmonious colors to create a simplified, almost childlike vision of architecture and nature. Blocks of color define the castle forms, while a vibrant red sun hangs in the sky, demonstrating his ability to evoke place and mood through abstract means.

Goldfish (1925), with its luminous central subject set against a dark, mysterious background containing symbolic elements, highlights Klee's fascination with aquatic life and his skill in creating magical, dreamlike atmospheres through color and form. Other notable works mentioned in various contexts include the dynamic Tänzerin (Dancer), the evocative landscape Park Near Lucerne (1938), the spatially complex Perspective of a Room with Occupants (1921), and the musically titled Duettino der Passanten.

Writings and Pedagogical Contributions

Paul Klee's influence extends beyond his paintings and drawings to his significant contributions as an art theorist and educator. His teaching at the Bauhaus was legendary for its intellectual rigor and imaginative depth. He sought to provide his students with a fundamental understanding of the elements of art – point, line, plane, color – and the dynamic forces that govern their interaction.

His Pedagogical Sketchbook (1925) remains a classic text in art education. In just over 50 pages, accompanied by numerous diagrams, Klee outlines his core concepts about the "active line" that moves freely, the interplay of structure and energy, and the relationship between natural forms and artistic creation. He uses analogies from physics, biology, and music to illuminate visual principles, encouraging students to think of form not as static but as generated through movement and process.

His posthumously published lecture notes, collected in volumes like The Thinking Eye, offer a much more extensive insight into his complex theoretical framework. They cover topics ranging from color theory and composition to the analysis of natural growth patterns and the philosophical dimensions of art. Klee believed that art should penetrate beneath the surface of reality to reveal the underlying creative forces. His famous dictum, "Art does not reproduce the visible; rather, it makes visible," encapsulates his belief in art's power to reveal hidden structures and meanings. His writings continue to be studied for their insights into the creative process and the foundations of visual language.

Shadows of History: The Nazi Era

Klee's successful career in Germany came to an abrupt end with the rise of the Nazi Party. Modern art was deemed "degenerate" (entartet) by the regime, and artists associated with movements like Expressionism, Cubism, and abstraction were persecuted. Klee, with his international reputation and association with the Bauhaus (itself a target of Nazi hostility), was quickly singled out.

In 1933, shortly after the Nazis came to power, Klee was dismissed from his teaching position at the Düsseldorf Academy of Arts, where he had moved after leaving the Bauhaus in 1931. His home was searched, and he faced increasing harassment. Recognizing the danger, Klee and his wife Lily emigrated to his native Switzerland in December 1933, settling back in Bern.

The persecution continued even after his departure. In 1937, seventeen of Klee's works were included in the infamous "Degenerate Art" exhibition organized by the Nazis in Munich to ridicule modern art. Over 100 of his works were confiscated from public collections in Germany, many subsequently sold abroad or lost. Despite being born in Switzerland, Klee faced bureaucratic hurdles in regaining Swiss citizenship (his father's German nationality had made him legally German), a process that was still incomplete at the time of his death. The political turmoil and personal upheaval cast a shadow over his later years.

Late Style and Final Years

The final phase of Klee's life, spent in exile in Bern, was marked by personal hardship but also extraordinary artistic productivity. In 1935, he began suffering from a mysterious illness, later diagnosed as progressive systemic sclerosis (scleroderma), a debilitating autoimmune disease affecting the skin and internal organs. The illness caused pain, fatigue, and physical limitations, profoundly impacting his life and work.

Despite his declining health, Klee's creative output surged, particularly in 1939 when he produced over 1,200 works. His late style often features heavier, darker lines, sometimes resembling hieroglyphs or pictograms. The scale of his works occasionally increased, and his themes frequently touched upon suffering, death, angels, demons, and the precariousness of existence. Works like Death and Fire (1940) convey a powerful sense of foreboding and mortality.

However, his late work is not solely defined by darkness. There are also pieces filled with resilience, grace, and even humor. His characteristic inventiveness and exploration of form and color continued. He worked intensely until the very end. Paul Klee died on June 29, 1940, in a sanatorium in Muralto-Locarno, Switzerland, at the age of 60. His ashes are interred at the Schosshaldenfriedhof in Bern.

The Man Behind the Art: Personality and Interests

Paul Klee was known as a quiet, introspective, and highly disciplined individual. His meticulous cataloging of his own work reflects an orderly mind. Yet, this intellectual rigor was combined with a rich inner life, a playful spirit, and a deep sensitivity. His diaries and letters reveal a thoughtful personality, capable of sharp observation and poetic expression.

His lifelong love for music, particularly Mozart and Bach, informed his sense of structure, rhythm, and counterpoint in painting. He continued to play the violin regularly throughout his life. His fascination with the theater, especially puppet shows and opera, is evident in the masks, costumes, and stage-like settings that appear in many works. He even created hand puppets for his son Felix between 1916 and 1925, which are now considered artworks in their own right.

Klee possessed a gentle, often ironic sense of humor, visible in many of his titles and drawings. He had a profound connection to nature, studying plants, flowers, fish, and geological formations, seeing in them models of organic growth and structure that informed his art. He collected natural objects like shells, stones, and pressed leaves. He also wrote poetry, further demonstrating the interplay between the verbal and the visual in his creative world. His art ultimately reflects a complex personality that harmonized intellect, intuition, childlike wonder, and a deep engagement with the world around him.

Enduring Legacy and Influence

Paul Klee's impact on the course of modern and contemporary art has been immense and multifaceted. His unique synthesis of abstraction and figuration, formal rigor and poetic fantasy, offered a compelling alternative to the dominant artistic trends of his time. He demonstrated that abstract art could be deeply personal, symbolic, and emotionally resonant.

His influence can be traced through numerous subsequent art movements and individual artists. The Surrealists admired his exploration of the subconscious and dream imagery, with artists like Max Ernst and Joan Miró showing affinities with his playful forms and automatic techniques. Abstract Expressionists in the United States, such as Mark Rothko, Adolph Gottlieb, and Theodoros Stamos, were drawn to his use of color, symbolic language, and spiritual undertones. His intricate surfaces and linear explorations also resonated with painters associated with Art Informel and Tachisme in post-war Europe.

Beyond specific movements, Klee's work continues to inspire artists who value subtlety, technical experimentation, and the integration of intellectual and intuitive approaches. His theories on form and color remain fundamental texts in art education worldwide. The Zentrum Paul Klee in Bern, Switzerland, opened in 2005 and designed by architect Renzo Piano, houses the world's largest collection of his works and serves as a major center for research and appreciation of his enduring legacy. He is celebrated as an artist who expanded the very definition of painting and drawing in the 20th century.

Klee in the Art Market

Reflecting his status as a pivotal figure in modern art, Paul Klee's works command significant prices and consistent interest in the international art market. Major auction houses like Christie's and Sotheby's regularly feature his paintings, watercolors, and drawings in their Impressionist and Modern Art sales, often achieving results well above estimates.

High-profile sales underscore the market's appreciation. In 2011, his 1922 work Tänzerin (Dancer) sold for £4,185,250 at Christie's London, setting a record for the artist at the time. In 2013, Castle and Sun (1928) reportedly sold for $20.8 million. Even his works on paper, such as drawings and sketchbooks, fetch substantial sums; a 1931 sketchbook sold for $325,000 in 2013.

Smaller works and prints are also actively traded, appearing not only at major auctions but also through galleries and online platforms like eBay, indicating a broad collector base. Estimated prices for works like Duettino der Passanten (€50,000-€70,000) and Akkord für ein Blumengarten (€30,000-€40,000) suggest the strong value placed even on less monumental pieces. The consistent demand and high valuations confirm Klee's established position within the canon of 20th-century masters and his ongoing appeal to collectors worldwide.

Conclusion

Paul Klee's artistic journey was one of constant exploration and synthesis. From his musical upbringing and early academic training to his pivotal encounters with the avant-garde and his influential tenure at the Bauhaus, he forged a path uniquely his own. He navigated the major art movements of his time but belonged fully to none, instead creating a deeply personal visual language that blended line and color, abstraction and representation, intellect and intuition. His work invites viewers into intricate worlds filled with whimsy, mystery, and profound insight into the nature of creativity and existence. As a painter, draftsman, theorist, and teacher, Klee left an indelible mark on 20th-century art, and his rich, multifaceted oeuvre continues to captivate and inspire generations.