Artus Wolffort (1581–1641) stands as a significant, if for a long time overlooked, figure in the vibrant artistic landscape of 17th-century Antwerp. A contemporary of giants like Peter Paul Rubens and Anthony van Dyck, Wolffort carved out his own niche, primarily as a painter of historical subjects, religious narratives, and, to a lesser extent, genre scenes. His work reflects the dynamic stylistic shifts of the Flemish Baroque, absorbing influences from Italian masters like Caravaggio while navigating the powerful artistic currents emanating from Rubens's workshop. This exploration delves into his life, artistic development, key works, and his enduring, though often subtly expressed, legacy within the rich tapestry of Flemish art.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Antwerp

Born in Antwerp in 1581, Artus Wolffort (sometimes spelled Wolffordt or Wolfordt) entered a city that was a crucible of artistic innovation and commercial activity. The early part of his training remains somewhat obscure, a common challenge when reconstructing the biographies of artists from this period who did not achieve immediate, widespread fame. However, it is known that he was enrolled as a pupil in the Antwerp Guild of Saint Luke in 1593, suggesting his formal artistic education began in his early teens. The Guild was the cornerstone of artistic life, regulating training and professional practice for painters, sculptors, and other craftsmen.

His initial artistic leanings were likely shaped by the prevailing late Mannerist styles that were still influential in Antwerp at the turn of the century. However, the artistic environment was on the cusp of a major transformation, largely driven by artists returning from Italy, bringing with them the revolutionary ideas of the early Baroque.

The Dordrecht Interlude and Return to Antwerp

Around 1603, Wolffort is documented as having moved to Dordrecht, an important city in the Dutch Republic. There, he married Maria Nouwens in 1605 and is recorded as joining the local Guild of Saint Luke in 1608, indicating he had achieved the status of an independent master. His time in Dordrecht, though not extensively documented in terms of specific commissions, would have exposed him to the developing artistic trends in the Northern Netherlands, which, while sharing roots with Flemish art, were beginning to diverge, particularly in their emphasis on realism and different subject matter. Painters like Abraham Bloemaert in Utrecht were already responding to Caravaggesque influences, and the general artistic climate was one of vigorous development.

Wolffort returned to Antwerp around 1615. This return marks a crucial phase in his career. He is documented as working as an assistant to Otto van Veen (also known as Otto Venius) from 1616. Van Veen was a highly respected and learned painter, known for his classicizing style and allegorical works. Significantly, Otto van Veen had also been one of the teachers of Peter Paul Rubens before Rubens's transformative journey to Italy. Working in van Veen's studio would have provided Wolffort with valuable experience, particularly in the organization of a large workshop and the execution of significant commissions. Van Veen's influence can be discerned in the more classical, somewhat restrained figures and compositions that characterize some of Wolffort's earlier works from this period.

The Pervasive Influence of Caravaggio

One of the defining characteristics of early 17th-century European painting was the profound impact of Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio. Caravaggio's dramatic use of chiaroscuro (strong contrasts between light and dark), his unidealized, naturalistic depiction of figures, and his ability to imbue religious scenes with intense human emotion resonated across the continent. While it's not definitively known if Wolffort ever travelled to Italy himself, Caravaggio's style was disseminated through various channels: prints, imported paintings, and, most importantly, by artists who had spent time in Rome and absorbed his innovations.

In Flanders, artists like Theodoor Rombouts and Gerard Seghers became notable exponents of Caravaggism. Wolffort, too, clearly absorbed elements of this style. This is evident in his use of tenebrism to heighten drama, his preference for depicting figures with a tangible, almost sculptural presence, and a focus on the psychological intensity of his subjects. His religious scenes often feature figures that, while dignified, possess a down-to-earth realism that breaks from the idealized conventions of earlier periods. This Caravaggesque leaning allowed him to create works of considerable emotional power and directness.

Navigating the Orbit of Peter Paul Rubens

By the time Wolffort was re-establishing himself in Antwerp, Peter Paul Rubens had returned from Italy (in 1608) and had rapidly become the dominant artistic force not only in Antwerp but across Europe. Rubens's dynamic, vibrant, and monumental Baroque style set a new standard. His workshop was a powerhouse, producing a vast number of altarpieces, mythological scenes, portraits, and designs for tapestries and prints.

For any artist working in Antwerp during this period, Rubens's presence was inescapable. Wolffort was no exception. While he maintained his own distinct artistic personality, his later works show an increasing assimilation of Rubenesque characteristics. This can be seen in more dynamic compositions, a richer and warmer palette, more robust and fleshy figure types, and a greater sense of movement and energy. It's important to note that this was not mere imitation; rather, Wolffort, like many of his contemporaries such as Jacob Jordaens and Gaspar de Crayer, adapted elements of Rubens's visual language to his own artistic ends. The influence was often one of general approach – a grander scale, more dramatic staging – rather than a direct copying of motifs. Some of Wolffort's works were, for a time, even misattributed to Rubens or his workshop, a testament to the quality he could achieve and his successful engagement with the prevailing Baroque idiom.

Anthony van Dyck, another towering figure from Rubens's circle, also left an indelible mark on Flemish art. While van Dyck was younger than Wolffort and primarily known for his elegant portraiture and refined religious scenes, his sophisticated handling of paint and emotive power also contributed to the rich artistic environment in which Wolffort operated.

Major Themes and Representative Works

Artus Wolffort's oeuvre is primarily composed of religious and historical paintings, often on a large scale, suitable for altarpieces or significant private commissions. He produced several series of works, including depictions of the Twelve Apostles and the Four Evangelists, which were popular subjects during the Counter-Reformation, emphasizing the foundations of the Church and the importance of scripture.

One of his most notable early works, often cited as showing the influence of Otto van Veen, is The Ascension of Christ (circa 1617), created for St. Paul's Church in Antwerp. This work, while demonstrating a clear narrative and competent handling of figures, has a certain classical restraint that would evolve in his later paintings.

A series depicting the Four Fathers of the Church (Ambrose, Augustine, Jerome, and Gregory) showcases his ability to create powerful, individualized character studies within a traditional iconographic framework. These figures are typically rendered with a strong sense of volume and dignity, often engaged in study or contemplation, their gravitas enhanced by dramatic lighting.

His Adoration of the Shepherds (various versions exist, e.g., one circa 1630) and Adoration of the Magi are themes he returned to, allowing for rich compositions with varied figures and an interplay of human emotion and divine presence. In these, one can often see a blend of Caravaggesque naturalism in the depiction of the shepherds or onlookers, combined with a more Baroque sense of dynamism in the overall arrangement.

The painting Jesus at the Pool of Bethesda is another example of his narrative skill, depicting the biblical scene of Christ healing the infirm. Such works required the ability to manage multiple figures, convey a complex story clearly, and evoke the appropriate spiritual atmosphere.

Wolffort also painted mythological subjects, though these are less common than his religious works. Scenes like Women Bathing demonstrate his capacity to handle the nude figure and create compositions with a sensuous appeal, aligning with a broader Baroque interest in classical mythology.

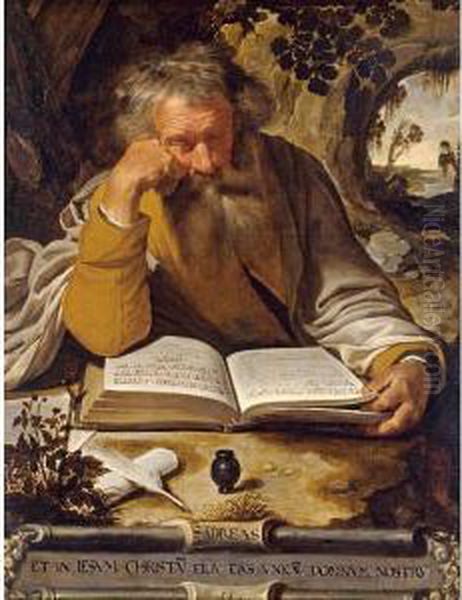

His genre scenes, such as Saint Andrew, often blur the line between religious portraiture and scenes of everyday life, presenting saints not as remote, ethereal beings but as relatable human figures. This approach, again, owes something to the Caravaggesque impulse to bring the sacred into the realm of the everyday.

Wolffort as a Teacher and His Workshop

Like many successful masters of his time, Artus Wolffort maintained a workshop and trained pupils. This was crucial for disseminating his style and for fulfilling larger commissions. Among his most notable pupils were Pieter van Lint and Pieter van Mol.

Pieter van Lint (1609–1690) worked as an apprentice in Wolffort's studio from around 1624 and became a master in the Antwerp Guild of Saint Luke in 1633. Van Lint later traveled to Italy, where he absorbed further influences, but his early work clearly shows the impact of Wolffort's style, particularly in figure types and compositional strategies. He went on to have a successful career, painting religious and mythological scenes, as well as portraits.

Pieter van Mol (1599–1650) was another significant pupil who later moved to Paris and became one of the founding members of the French Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture. His style also reflects the training he received under Wolffort, adapted to the tastes of the French court.

The presence of these and other, less documented, assistants and pupils indicates that Wolffort's studio was an active center of production. The extent of workshop collaboration in his larger pieces is a subject for art historical investigation, as is common for many artists of this era, including even Rubens himself, whose workshop practices were extensive.

Later Career and Mature Style

In his later career, from the 1630s until his death in 1641, Wolffort's style continued to evolve. The influence of Rubens became more pronounced, leading to works of greater dynamism and painterly freedom. His figures often became more robust, his compositions more complex and animated, and his use of color richer. However, he generally retained a certain solidity and a more controlled brushwork compared to the sheer bravura of Rubens or the fluid elegance of van Dyck.

Works from this period, such as The Assumption of the Virgin, demonstrate his ability to handle large-scale, multi-figure compositions with a sense of grandeur and emotional uplift, fully embracing the aspirations of Counter-Reformation art. These altarpieces aimed to inspire awe and devotion in the faithful, and Wolffort proved adept at fulfilling such commissions.

He continued to receive commissions for churches and private patrons. His reputation, while perhaps not on the level of the absolute top tier of Antwerp masters, was solid, and he was a respected member of the artistic community.

The Period of Obscurity and Scholarly Rediscovery

Despite a productive career, Artus Wolffort's name and work fell into relative obscurity for a considerable period after his death. This was not uncommon for artists who were highly competent and respected in their own time but were overshadowed by truly exceptional talents like Rubens. Many of his unsigned works, or those whose provenance became confused, were often misattributed to other artists, including Rubens, members of Rubens's workshop, or other contemporaries like Abraham Janssens or Theodoor van Loon.

The process of rediscovering and re-evaluating Wolffort's oeuvre began in earnest in the latter half of the 20th century. Art historians, notably Dr. Hans Vlieghe, played a crucial role in identifying his signed works and, through stylistic analysis, reconstructing his catalogue raisonné. This scholarly work involved meticulously comparing authenticated paintings with unattributed pieces, tracing workshop practices, and understanding his stylistic development. The identification of his distinctive hand – characterized by particular figure types, facial features, and compositional preferences – allowed for a more accurate assessment of his contribution.

This rediscovery has led to a greater appreciation of his skill and his place within the Flemish Baroque. Museums and collections have reattributed works to him, and his paintings now feature in exhibitions and art historical studies as an important representative of his era.

Wolffort's Place Among Contemporaries

To fully appreciate Wolffort, it's useful to consider him in relation to other Flemish artists of his time. Beyond Rubens and van Dyck, Antwerp was teeming with talent. Jacob Jordaens, for instance, was a powerful and earthy painter whose style, while also influenced by Rubens, had its own distinct character. Frans Snyders and Paul de Vos excelled in animal painting and large hunting scenes, often collaborating with Rubens and Jordaens. Jan Brueghel the Elder and Jan Brueghel the Younger were renowned for their detailed flower paintings and landscapes. Figure painters like Cornelis de Vos specialized in portraiture and religious scenes with a particular warmth and intimacy.

In this competitive environment, Wolffort distinguished himself through his consistent production of high-quality history paintings. He may not have possessed the revolutionary genius of Rubens or the refined elegance of van Dyck, but he was a master of his craft, capable of producing works of considerable power, dignity, and emotional resonance. He successfully synthesized various influences – the classicism of van Veen, the drama of Caravaggio, and the dynamism of Rubens – into a personal style that found favor with patrons.

His relationship with the broader artistic trends can also be seen in comparison to artists active in other centers. For example, in Utrecht, painters like Hendrick ter Brugghen and Gerrit van Honthorst were more direct adherents of Caravaggism. In Amsterdam, Rembrandt van Rijn was forging his own unique path, also deeply engaged with light and shadow but with a different psychological depth. Wolffort's art remains firmly rooted in the Antwerp tradition, which, while open to Italian influences, retained its own Flemish character.

Legacy and Conclusion

Artus Wolffort died in Antwerp in 1641. His legacy is that of a skilled and dedicated painter who made a significant contribution to the religious and historical art of the Flemish Baroque. While overshadowed for centuries by his more famous contemporaries, modern scholarship has rightfully restored him to a position of respect.

His influence extended through his pupils, Pieter van Lint and Pieter van Mol, who carried elements of his style into their own successful careers, both in Flanders and abroad. His works are now found in various museums and private collections, including the Victoria and Albert Museum in London and the Musée d'Orsay in Paris (though holdings can change, and many works are in Belgian churches and museums like the Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp).

Wolffort's art exemplifies the richness and diversity of the Antwerp school during its golden age. He was an artist who understood the demands of his patrons, particularly the Church during the Counter-Reformation, and who could deliver works that were both doctrinally sound and artistically compelling. His journey from the workshop of Otto van Veen, through an engagement with Caravaggesque realism, to an assimilation of Rubenesque dynamism, charts a course typical of many talented artists of his generation who sought to forge their own voice within a powerful artistic tradition. Artus Wolffort remains a testament to the depth of talent that flourished in 17th-century Antwerp, a master whose works continue to reward study and appreciation.