Nicolas Tournier stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the landscape of French Baroque art. Active during the first half of the 17th century, he was a prominent exponent of Caravaggism in France, particularly in the southern regions. His work is characterized by its dramatic use of chiaroscuro, its poignant human figures, and its adept fusion of Italianate influences with a distinctly French sensibility. Though his career was relatively short, and aspects of his life remain debated by scholars, his artistic legacy endures through powerful canvases that continue to engage and move viewers.

Early Life and Artistic Genesis

Nicolas Tournier was born in Montbéliard, then part of the Duchy of Württemberg and a Protestant enclave, around 1590. His father, André Tournier, was a painter described as hailing from Besançon and also a Protestant. This familial connection to the arts undoubtedly provided an early exposure to the painter's craft for young Nicolas. The religious context of his upbringing in a Protestant family is noteworthy, especially considering his later career, which included significant Catholic commissions and a period spent in the heart of Catholic Europe, Rome.

Details of Tournier's earliest training remain scarce. It is presumed he received initial instruction from his father. However, the artistic environment of Montbéliard, while respectable, would not have offered the cosmopolitan exposure necessary for an ambitious young painter. Like many artists of his generation from Northern Europe, the allure of Italy, and particularly Rome, as the epicenter of artistic innovation and classical heritage, would have been irresistible.

The Roman Sojourn: Embracing Caravaggism

Tournier's presence in Rome is documented from approximately 1619 to 1626. This period was transformative. Rome at this time was still reverberating with the artistic revolution ignited by Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (1571-1610). Though Caravaggio himself was deceased, his radical naturalism, dramatic use of tenebrism (the intense contrast of light and dark), and emotionally charged depictions of religious and secular scenes had captivated a generation of artists from across Europe. These followers, known as the Caravaggisti, adopted and adapted his style.

In this vibrant artistic milieu, Tournier found his voice. He is believed to have associated closely with the circle of Bartolomeo Manfredi (c. 1582-1622), an Italian painter who was instrumental in popularizing Caravaggio's themes and compositions, particularly genre scenes of everyday life, musicians, drinkers, and soldiers. Manfredi's "Manfrediana methodus" (Manfredi's method) involved depicting such scenes with a focus on realism and dramatic lighting, and Tournier clearly absorbed these lessons.

Another crucial figure in Tournier's Roman development was Valentin de Boulogne (1591-1632), a French painter who was a leading Caravaggist in Rome. Some scholars suggest Tournier may have even been a pupil of Valentin, or at least worked in close proximity. Their styles share a certain gravity, a penchant for melancholic figures, and a sophisticated handling of light. The camaraderie among French artists in Rome, often congregating in specific neighborhoods and supporting one another, would have provided a fertile ground for artistic exchange. Other Caravaggisti active in Rome during or around this period, whose work contributed to the general artistic atmosphere, included Italian masters like Orazio Gentileschi and his daughter Artemisia Gentileschi, the Spaniard Jusepe de Ribera (Lo Spagnoletto), and Northern European painters like Gerrit van Honthorst and Dirck van Baburen from Utrecht.

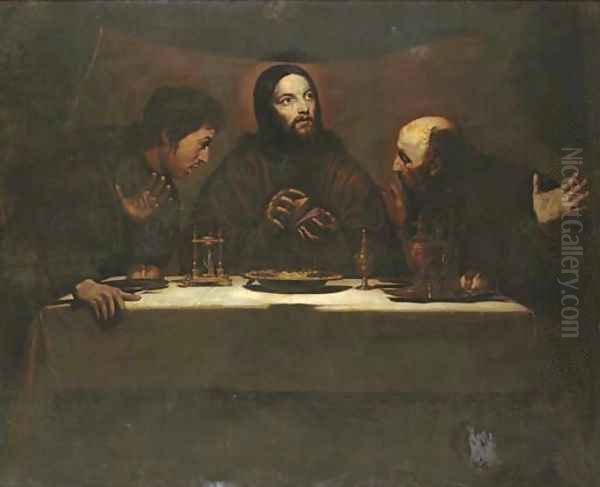

During his Roman years, Tournier produced a range of works. These included genre scenes, such as depictions of concerts, card players, and soldiers in guardrooms, which were popular among collectors. These paintings often feature half-length figures, brought close to the picture plane, illuminated by a strong, often unseen, light source that casts deep shadows, heightening the drama and psychological intensity of the scene. His figures, while robust and realistically rendered, often possess a certain elegance and introspective quality.

Key Roman Works and Stylistic Traits

Several paintings are attributed to Tournier's Roman period, showcasing his mastery of the Caravaggesque idiom. "A Musical Party" (or "The Concert") is a quintessential example, depicting a group of musicians and a singer, their faces and instruments highlighted against a dark background. The interplay of light on textures—fabric, skin, polished wood—is expertly rendered, and the figures convey a sense of shared experience and quiet concentration. Such scenes allowed Tournier to explore human interaction and individual character within a confined, dramatically lit space.

Another notable work often cited from this period is "The Guardroom Scene," where soldiers are shown drinking and dicing. The painting captures the rough camaraderie and underlying tension of such gatherings. The figures are individualized, their expressions and postures conveying distinct personalities. The strong chiaroscuro emphasizes the three-dimensionality of the forms and focuses the viewer's attention on key narrative elements. Similarly, works like "The Drinker" or "Dice Players" further exemplify his engagement with Manfredi's themes, often imbued with a moralizing undertone common in genre painting of the era.

Religious subjects also occupied Tournier during his time in Rome. Paintings like "The Denial of Saint Peter" demonstrate his ability to convey profound religious emotion through the Caravaggesque style. The dramatic lighting underscores Peter's inner turmoil and the gravity of the moment. His Roman works are generally characterized by precise lines, a somewhat cool palette often enlivened by touches of rich color (especially reds and ochres), and a careful, almost sculptural modeling of figures. There's a palpable sense of stillness and psychological depth in his Roman oeuvre.

The question of Tournier's religious convictions during this period is interesting. While born Protestant, his immersion in Catholic Rome and his later focus on Catholic commissions in France suggest a possible conversion, a common occurrence for artists seeking patronage in Catholic countries. However, definitive proof remains elusive.

Return to France: A Southern Master

Around 1626, Nicolas Tournier left Rome and returned to France. He did not, however, settle in Paris, the burgeoning artistic capital of the kingdom. Instead, he chose to establish himself in the south of France. He is first recorded in Carcassonne, a city with a rich medieval history. By 1632, he had moved to Toulouse, a major regional center with a vibrant cultural life and significant opportunities for artistic patronage from religious institutions and wealthy citizens.

His decision to work in Southern France is significant. While Paris was increasingly looking towards a more classical, academic style, influenced by artists like Simon Vouet (who had also returned from Italy but adapted his style) and later Nicolas Poussin, the south remained more receptive to the dramatic naturalism of Caravaggism. Tournier became one of the leading figures, if not the foremost, of this style in the region.

In Toulouse, Tournier's focus shifted predominantly towards large-scale religious commissions for churches and convents. This change in emphasis reflects the patronage available in the region, which was deeply marked by the Counter-Reformation and its demand for art that could inspire piety and devotion. His style, while retaining its Caravaggesque foundations, began to evolve. Some art historians note a slight softening of his chiaroscuro in certain later works, perhaps a subtle move towards a greater clarity or a response to local tastes, though the dramatic interplay of light and shadow remained a hallmark.

Major French Commissions and Later Works

Among Tournier's most celebrated works from his Toulouse period is "The Carrying of the Cross." One version of this subject, now in the Musée des Augustins in Toulouse, and another, "Christ Carried to the Tomb" (sometimes also referred to as "The Entombment" or a variation of "The Carrying of the Cross"), now in the Louvre Museum, Paris, exemplify his mature style. These are profoundly moving works, characterized by their somber palette, the monumental gravity of the figures, and the intense, yet restrained, emotional expression. The figures of Christ, Mary, and the disciples are rendered with a powerful realism, their grief and suffering made palpable through their gestures and facial expressions. The dramatic lighting isolates the figures against a dark void, concentrating the viewer's focus on the sacred drama.

Another significant, though somewhat enigmatic, large-scale painting is "The Battle of Constantine," also housed in the Musée des Augustins. This complex, multi-figure composition depicts a dynamic battle scene. Art historians have noted a potential influence from Piero della Francesca's famous fresco cycle "The Legend of the True Cross" in Arezzo, particularly in the depiction of horses and the classical arrangement of figures. This suggests Tournier's artistic vocabulary was not limited solely to Caravaggism but also drew upon earlier Renaissance masters, a testament to his broader artistic education.

Other important religious works from this period include "The Lamentation over the Dead Christ," where the sorrow of the Virgin and other mourners is conveyed with a quiet dignity and profound pathos. His ability to render human emotion with subtlety and power is a consistent feature of his religious paintings. He also continued to receive commissions for portraits and possibly other secular subjects, though his reputation in Toulouse was primarily built on his religious altarpieces.

His workshop in Toulouse likely included assistants and pupils, such as Jean-François Clouet and Antoine Clouet, who would have helped propagate his style in the region. Through these commissions and his workshop, Tournier exerted a considerable influence on the artistic production of Southern France.

Artistic Style and Techniques Revisited

Throughout his career, Nicolas Tournier's art was defined by several key characteristics. His mastery of chiaroscuro, learned in Rome, remained central. He used light not just for illumination but as a powerful compositional and expressive tool, creating dramatic contrasts that guide the eye, model form, and heighten emotional impact. His figures are typically solid and well-defined, possessing a sculptural quality.

Tournier's realism was tempered with a certain idealism and elegance, particularly in the rendering of faces and hands. Unlike some Caravaggisti who emphasized the raw, even brutal, aspects of reality, Tournier's figures often possess a refined, sometimes melancholic, beauty. His compositions are carefully constructed, often employing diagonal lines to create dynamism, or stable, pyramidal arrangements for more iconic religious scenes.

His palette, while often dominated by dark tones, could incorporate rich, saturated colors, particularly deep reds, blues, and ochres, which add to the visual richness of his canvases. The psychological depth he achieved in his figures, whether in a boisterous tavern scene or a solemn religious narrative, is a testament to his skill as an observer of human nature.

Influence, Legacy, and Art Historical Assessment

Nicolas Tournier's influence was most pronounced in Southern France, particularly in and around Toulouse. He was a key conduit for the dissemination of Caravaggesque naturalism in this region, a style that persisted there longer than in Paris. He stands alongside Georges de La Tour as one of the most distinctive and sensitive French interpreters of Caravaggio's legacy, though La Tour's highly personal and simplified geometric style ultimately diverged more radically from their common Roman roots.

Compared to contemporaries like Nicolas Poussin, who championed a classical, intellectual approach to painting, or Simon Vouet, who adapted Italian Baroque grandeur to French tastes, Tournier's commitment to a more direct, emotionally resonant naturalism set him apart. His work offers a different facet of French Baroque art, one less aligned with the official courtly style developing in Paris and more attuned to provincial religious sensibilities and the enduring appeal of Caravaggio's dramatic vision.

For many years, Tournier, like many Caravaggisti, fell into relative obscurity after his death (believed to be around 1639, though some earlier sources cited 1657, the former is now more widely accepted). The rise of Neoclassicism and later artistic movements overshadowed Baroque naturalism. However, the 20th-century reassessment of Baroque art, and particularly the renewed appreciation for Caravaggio and his followers, led to a rediscovery of Tournier's work.

Attribution remains a challenge for scholars of Tournier, as it does for many artists of this period. Some works once attributed to him have been reassigned to other artists, such as Valentin de Boulogne or Bartolomeo Manfredi, and vice-versa. The close stylistic similarities among artists working in the Caravaggesque mode in Rome can make definitive attributions difficult without documentary evidence. However, a core body of work is now securely attributed to him, allowing for a clearer understanding of his artistic development and contribution.

Conclusion: An Enduring Light

Nicolas Tournier was a painter of considerable talent and sensitivity. From his formative years in Montbéliard to his transformative period in Rome and his mature career in Southern France, he consistently produced works of compelling power and beauty. As a key French Caravaggist, he masterfully employed the dramatic language of light and shadow to explore a range of human experiences, from the conviviality of secular gatherings to the profound mysteries of faith. While he may not have achieved the widespread fame of some of his contemporaries, his paintings hold an important place in the history of French art, representing a vital and enduring strand of Baroque naturalism. His ability to imbue his figures with psychological depth and to create compositions of striking visual impact ensures that Nicolas Tournier's art continues to resonate with audiences today, a testament to his skill as a storyteller in paint and a master of the Baroque aesthetic.