August Friedrich Albrecht Schenck stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the rich tapestry of 19th-century European art. A Danish-born artist who found his home and fame in France, Schenck carved a distinct niche for himself as a painter of animals and landscapes, imbuing his subjects with a profound emotional depth that resonated deeply with contemporary audiences and continues to captivate viewers today. His works, particularly those depicting sheep in moments of peril or pathos, transcend mere animal portraiture, exploring universal themes of suffering, loyalty, and the raw, often harsh, realities of nature. This exploration will delve into his life, his artistic development, his most celebrated works, and his place within the broader context of 19th-century art, particularly the flourishing genre of animalier painting.

Early Life and Formative Influences

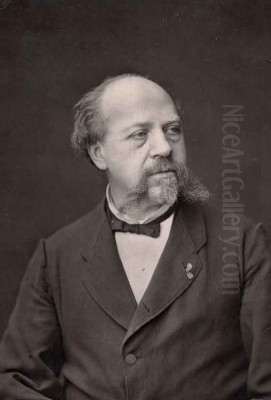

August Friedrich Albrecht Schenck was born on April 23, 1828, in Glückstadt, a town in the Duchy of Holstein. At the time of his birth, Holstein was under Danish rule but also part of the German Confederation, a geopolitical complexity that sometimes led to his nationality being described as German. However, he is more accurately identified as Danish by birth. His early life was not immediately set on an artistic path. Like many young men of his era seeking fortune and adventure, Schenck initially ventured into the world of commerce. This pursuit led him to spend time in England and later in Portugal, where he worked as a wine merchant.

These early experiences abroad, though not directly artistic, likely broadened his horizons and perhaps instilled in him a keen sense of observation and an understanding of different cultures and environments. It was only after these commercial endeavors that Schenck felt the undeniable pull towards art. He made the pivotal decision to move to Paris, the undisputed art capital of the world in the 19th century, to formally pursue his artistic education. This move marked the true beginning of his journey as a painter.

Academic Training in Paris

Upon arriving in Paris, Schenck enrolled in the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts, the leading art institution in France. This academy was the bastion of traditional artistic training, emphasizing rigorous instruction in drawing, anatomy, perspective, and the study of Old Masters. Here, Schenck would have been immersed in a curriculum designed to produce artists capable of executing large-scale historical, mythological, or religious paintings, though the skills acquired were transferable to any genre.

Crucially, Schenck became a pupil of Léon Cogniet (1794-1880). Cogniet was a highly respected painter and an influential teacher at the École des Beaux-Arts. He was known for his historical paintings, such as Tintoretto Painting His Dead Daughter (1843), and portraits, but his studio was a training ground for a diverse range of talents. Under Cogniet's tutelage, Schenck would have honed his technical skills, particularly in draughtsmanship and the realistic depiction of form. Cogniet's emphasis on careful observation and anatomical accuracy would have been invaluable for an aspiring animal painter. The master's influence likely extended beyond mere technique, possibly shaping Schenck's approach to narrative and emotional expression in his art.

Emergence as an Animalier

Schenck made his debut at the Paris Salon in 1857. The Salon was the official art exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts and the most important venue for an artist to gain recognition and patronage in France. His regular participation in the Salon from this point onwards signaled his commitment to his artistic career and his gradual integration into the Parisian art world. While he also painted landscapes, it was his animal subjects that quickly brought him acclaim.

The 19th century witnessed a remarkable flourishing of animal painting, or animalier art, as it became known in France. This genre was elevated from its previously lower status in the academic hierarchy, partly due to the Romantic movement's emphasis on nature and emotion, and later by the Realist movement's focus on everyday subjects. Artists like Théodore Géricault (1791-1824), with his powerful depictions of horses, and Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863), with his dramatic hunting scenes and portrayals of wild animals, had already paved the way for a more dynamic and expressive approach to animal subjects. Schenck entered this field at a time when public interest in animal art was high.

Thematic Focus: Sheep and the Drama of Nature

Schenck became particularly renowned for his paintings of sheep. This might seem a humble subject, but in Schenck's hands, these animals became vehicles for profound emotional narratives. He often depicted them in dramatic, even tragic, circumstances – caught in snowstorms, threatened by predators, or mourning their dead. These scenes were not merely sentimental; they were imbued with a sense of realism and an understanding of animal behavior that resonated with a public increasingly interested in the natural world.

His choice of sheep was significant. These animals, often seen as symbols of innocence and vulnerability, allowed him to explore themes of suffering, endurance, and maternal devotion. The harsh, often snowy landscapes that frequently formed the backdrop to his sheep paintings amplified the sense of struggle and isolation. Artists like Charles Jacque (1813-1894), a member of the Barbizon School, also famously depicted sheep, but often in more pastoral, tranquil settings, though Jacque too could capture the more rugged aspects of their existence. Schenck’s focus, however, leaned more consistently towards the dramatic and the poignant.

Anguish (Angoisse): A Masterpiece of Emotional Power

Schenck's most famous work, and arguably his masterpiece, is Anguish (also known by its French title, Angoisse, or L'Orphelin, souvenir d'Auvergne), painted around 1878. This powerful and moving painting is now a prized possession of the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne, Australia, where it has consistently been one of the most popular works in the collection since its acquisition in 1880.

The painting depicts a ewe standing protectively over the body of her dead lamb in a bleak, snow-covered landscape. Her head is raised in a mournful cry, her breath visible in the frigid air. A murder of crows circles ominously overhead, waiting to descend upon the carcass, their dark forms contrasting sharply with the white snow and the pale wool of the sheep. The mother's grief and defiance in the face of overwhelming loss and impending threat are palpable. Schenck masterfully captures the raw emotion of the scene, transforming a simple animal tragedy into a universal symbol of maternal love and sorrow.

The composition is stark and effective. The diagonal line of the snowdrift leads the viewer's eye towards the central figures, while the vast, empty expanse of the snowy landscape emphasizes their isolation and vulnerability. The muted palette of whites, greys, and browns enhances the somber mood. Anguish is a prime example of Schenck's ability to combine meticulous realism in the depiction of the animals and their environment with a deeply Romantic sensibility. The painting's enduring popularity speaks to its success in evoking a powerful empathetic response from viewers.

Other Notable Works and Artistic Style

While Anguish remains his best-known painting, Schenck produced a considerable body of work throughout his career. Works such as The Awakening and Repose on the Seashore (or Seabirds Resting) showcase his versatility within the animal and landscape genres. His depictions of dogs were also well-regarded. In all his works, a consistent characteristic is his ability to capture the unique character and emotional state of his animal subjects.

Schenck's style can be described as a blend of Naturalism and Romanticism. His meticulous attention to anatomical detail, the texture of fur and wool, and the specificities of the natural environment align with the tenets of Naturalism, a movement that sought to depict the world with scientific objectivity. Artists like Gustave Courbet (1819-1877), a leading figure of Realism (a precursor to Naturalism), emphasized unvarnished truth in their depictions of rural life and nature, and this ethos certainly informed animal painting.

However, Schenck's work also possesses a strong Romantic undercurrent. The dramatic scenarios, the emphasis on intense emotion, and the often sublime or threatening aspects of nature are hallmarks of Romanticism. He was less interested in the purely objective depiction of animals than in conveying their inner lives and their struggles against the forces of nature, much like the British painter Sir Edwin Landseer (1802-1873), whose works like The Monarch of the Glen or The Old Shepherd's Chief Mourner similarly combined realism with strong emotional narratives and anthropomorphic tendencies.

Context: The Animalier Movement and Contemporaries

Schenck was working within a vibrant and competitive field. The 19th century saw a surge in artists specializing in animal subjects, known as animaliers. In France, Antoine-Louis Barye (1795-1875) was a towering figure, primarily a sculptor but also a painter, renowned for his dynamic and anatomically precise depictions of wild animals in combat. Rosa Bonheur (1822-1899) was another immensely successful contemporary of Schenck, celebrated internationally for her large-scale, realistic paintings of animals, such as The Horse Fair (1852-55). Bonheur, like Schenck, combined meticulous observation with a deep empathy for her subjects. Their careers often ran parallel, and they were, in a sense, competitors in the popular genre of animal painting.

The Barbizon School painters, active from the 1830s to the 1870s, also played a crucial role in elevating landscape and rural scenes, often incorporating animals. Besides Charles Jacque, artists like Constant Troyon (1810-1865) became famous for his depictions of cattle in luminous landscapes. Jean-François Millet (1814-1875), though primarily focused on peasant figures, often included farm animals in his compositions, rendered with a similar sense of dignity and realism, as seen in works like Shepherdess with her Flock.

The public's appetite for animal paintings was fueled by various factors: a growing middle-class patronage, increased interest in natural history spurred by scientific advancements, and a Romantic nostalgia for rural life in an era of rapid industrialization. Schenck's success can be attributed to his ability to tap into these sensibilities while bringing his unique emotional intensity to the genre.

Life in Écouen and Later Career

Schenck spent most of his productive life in France. He eventually settled in Écouen, a village about 20 kilometers north of Paris. Écouen was home to a colony of artists, attracted by its picturesque setting and proximity to the capital. Living and working in this artistic community likely provided Schenck with a supportive and stimulating environment. He continued to exhibit regularly at the Paris Salon and other exhibitions, solidifying his reputation.

His dedication and skill did not go unrecognized by the French artistic establishment. In 1885, August Schenck was awarded the Chevalier de la Légion d'Honneur (Knight of the Legion of Honour), one of France's highest civilian decorations. This honor was a significant acknowledgment of his contributions to French art and a testament to the esteem in which he was held.

Schenck's work found an appreciative audience not only in France but also internationally. The acquisition of Anguish by the National Gallery of Victoria in Australia is a case in point, indicating his reach beyond Europe. His paintings were also collected in America and other parts of Europe. While perhaps not achieving the same level of global fame as Rosa Bonheur or Landseer, Schenck was a respected and successful artist in his time.

The Enduring Appeal of Schenck's Art

The power of Schenck's art lies in its ability to evoke empathy. By focusing on moments of vulnerability and distress, he encouraged viewers to connect with the emotional lives of animals. This was particularly relevant in the 19th century, a period that saw the rise of animal welfare movements and increased public concern about cruelty to animals. Schenck's paintings, whether intentionally or not, contributed to this growing awareness by humanizing his animal subjects.

His depictions of sheep, in particular, carry a certain allegorical weight. Sheep have long been symbolic in Western culture, often representing innocence, sacrifice, and the flock guided by a shepherd (a common religious metaphor). Schenck's scenes of sheep in peril could be interpreted on multiple levels – as straightforward depictions of animal life, as commentaries on the harshness of nature, or even as reflections on human vulnerability and suffering.

Consider the artistic lineage: Dutch Golden Age painters like Paulus Potter (1625-1654), with his famous work The Young Bull, had already established a tradition of realistic animal depiction. Later, in the 18th century, artists like Jean-Baptiste Oudry (1686-1755) in France and George Stubbs (1724-1806) in England brought new levels of anatomical accuracy and psychological insight to animal portraiture, particularly with dogs and horses. Schenck built upon this legacy, infusing it with the dramatic intensity and emotionalism characteristic of his era.

Legacy and Conclusion

August Friedrich Albrecht Schenck passed away on January 1, 1901, in Écouen, the town that had been his home for many years. He was buried there, leaving behind a significant body of work that continues to be appreciated for its technical skill and emotional depth.

While the grand narratives of art history often focus on avant-garde movements and revolutionary figures, artists like Schenck played a vital role in shaping the artistic landscape of their time. He excelled within an established genre, bringing to it his unique sensibility and creating works that resonated deeply with the public. His ability to capture the "Angst" of the animal kingdom, as vividly portrayed in his masterpiece Anguish, ensures his place as a memorable and important animalier painter of the 19th century.

His paintings serve as a reminder of the enduring power of art to connect us to the natural world and to evoke our deepest emotions. In an age where the relationship between humans and animals continues to be a complex and often fraught subject, Schenck's compassionate portrayals of animal life remain remarkably relevant. He was more than just a painter of sheep; he was a painter of shared emotions, a chronicler of the silent struggles that bind all living creatures. His legacy is preserved not only in the collections of major museums but also in the hearts of those who are moved by his poignant and powerful imagery. Through his dedicated brushwork and empathetic vision, Schenck ensured that the often-unseen dramas of the animal world were brought into the light, compelling viewers to look, to feel, and to remember.