Introduction: The Animal Kingdom's Premier Portraitist

Sir Edwin Henry Landseer stands as one of the most celebrated and complex figures in nineteenth-century British art. Born in London in 1802 and passing away in 1873, his life spanned a period of immense social and cultural change, much of which found reflection in his work. Primarily renowned as a painter of animals, Landseer possessed an extraordinary ability to capture not only the physical likeness of his subjects but also to imbue them with personality, emotion, and often, allegorical significance. His skills extended beyond painting to sculpture and engraving, securing his place as a versatile and profoundly influential artist. Patronized by royalty and adored by the public, Landseer's art became synonymous with the Victorian era's sensibilities, tastes, and even its moral outlook.

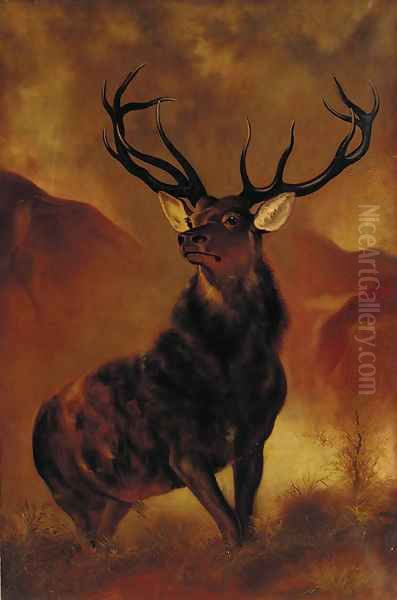

Landseer's fame was built on his unparalleled depictions of dogs, horses, stags, and lions, rendered with meticulous anatomical accuracy yet infused with a dramatic or sentimental narrative that resonated deeply with his contemporaries. From the majestic Highland stag in The Monarch of the Glen to the heroic Newfoundland in Saved, his creations became iconic images, widely disseminated through engravings and shaping popular perceptions of the animal world. He moved comfortably within the highest echelons of society, counting Queen Victoria and Prince Albert among his most ardent admirers, yet his work also found unprecedented popularity among the burgeoning middle class. Despite his immense success, his later life was marked by personal struggles, adding a layer of pathos to his artistic legacy. This exploration delves into the life, work, and enduring impact of Sir Edwin Landseer, a true master of his craft.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Edwin Henry Landseer was born on March 7, 1802, in Marylebone, London. His artistic inclinations were nurtured from an exceptionally young age, heavily influenced by his family environment. His father, John Landseer, was a respected engraver and writer on art, ensuring that Edwin and his siblings were immersed in creative pursuits. John recognized his son's prodigious talent early on, encouraging him to sketch animals from life, often taking him to Hampstead Heath to draw donkeys, goats, and sheep, and later to Exeter Change menagerie to study more exotic creatures like lions and tigers.

This early, intensive focus on direct observation and anatomical study formed the bedrock of Landseer's artistic practice. His father wasn't his only early guide; the historical painter Benjamin Robert Haydon also played a significant role. Haydon, known for his grand, ambitious canvases and his emphasis on anatomical correctness (even through dissection), encouraged the young Landseer to study animal anatomy rigorously, including the structure of muscles and bones. This training instilled in Landseer a profound understanding of animal form that would distinguish his work throughout his career.

Landseer's talent developed at a remarkable pace. He was exhibiting drawings at the Royal Academy of Arts by the tender age of 13, an astonishing feat that signaled the arrival of a major new talent. His precocity was undeniable, and the London art world quickly took notice. His brothers, Thomas Landseer (who would become a renowned engraver, crucial to disseminating Edwin's work), Charles Landseer (later Keeper of the Royal Academy), and Arthur Ernest Landseer, also pursued artistic careers, making the Landseers a notable family within the British art scene. Edwin, however, was clearly the star.

Training at the Royal Academy and Early Success

Formalizing his training, Edwin Landseer enrolled in the Royal Academy Schools in 1816, at the age of fourteen. Here, he further honed his skills under the tutelage of established artists, although his foundational understanding, particularly of animal anatomy gained under Haydon and through personal study, was already remarkably advanced. His presence at the Academy solidified his position as a rising figure, and his works continued to attract attention at the annual exhibitions.

His early paintings already demonstrated the hallmarks of his mature style: technical brilliance, anatomical precision, and an engaging subject matter. Works exhibited during his teenage years and early twenties, such as Fighting Dogs Getting Wind (exhibited 1818) or studies of lions and tigers, showcased his ability to capture animals in moments of intense action or quiet repose. Early narrative paintings like The Shepherd's Last Mourn (likely related to the famous The Old Shepherd's Chief Mourner) and The Faithful Hound began to explore the sentimental and emotional connections between humans and animals, themes that would become central to his oeuvre.

The critical acclaim for these early works was significant. They were praised for their lifelike quality and the artist's evident understanding of his subjects. Landseer wasn't just painting animals; he was portraying animal character. This ability to suggest intelligence, loyalty, or ferocity in his animal subjects set him apart from mere animal painters and positioned him as a serious artist capable of tackling complex themes through the lens of the natural world. His reputation grew rapidly, laying the groundwork for his election to the Royal Academy.

Election to the Royal Academy and Growing Reputation

Landseer's ascent within the formal structures of the British art world was swift. In 1826, at the remarkably young age of 24, he was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA). This prestigious recognition confirmed his status as one of the leading artists of his generation. Just five years later, in 1831, he achieved the highest rank, becoming a full Royal Academician (RA) at the age of 31. These accolades were a testament to his consistent excellence and the immense popularity of his work.

Throughout the 1820s and 1830s, Landseer produced a series of paintings that cemented his fame. Works like The Hunting of Chevy Chase (1825-26), a large and dramatic scene inspired by the traditional ballad and featuring vigorous depictions of hounds and deer, showcased his ambition and skill in handling complex compositions. The Larder Invaded (1822) displayed his knack for humorous observation, depicting a mischievous dog raiding a pantry. These works demonstrated his versatility, moving between historical subjects, sporting scenes, and intimate animal portraits.

His visits to Scotland, beginning in 1824 often in the company of fellow artist Charles Robert Leslie or writer Sir Walter Scott, proved immensely influential. The rugged landscapes of the Scottish Highlands and the majestic stags that roamed them provided powerful inspiration. This period saw the beginning of his fascination with Highland themes, which would lead to some of his most iconic paintings later in his career. His ability to capture the specific atmosphere and wildlife of Scotland added another dimension to his appeal.

Thematic Focus: Animals, Anthropomorphism, and Narrative

The cornerstone of Landseer's art is his profound engagement with the animal kingdom. While technically brilliant in depicting landscapes and occasionally human figures, it was his portrayal of animals that defined his career. He possessed an uncanny ability to render fur, feather, and hide with convincing texture and detail, combined with an unerring sense of anatomical structure and natural posture. His animals are palpably real, possessing weight, movement, and vitality.

However, Landseer went beyond mere realistic depiction. He became a master of anthropomorphism – the attribution of human characteristics, emotions, and motivations to animals. This was a key element of his popular appeal in the Victorian era, a time when sentimentality and moral narratives were highly valued. His dogs often display loyalty, mischief, courage, or pathos; his stags embody nobility and wildness; even his lions project a sense of regal power.

This anthropomorphism often served a narrative or allegorical purpose. In Laying Down the Law (1840), a group of dogs are arranged in a courtroom setting, with a wise-looking poodle presiding as judge, gently satirizing the legal profession. In Dignity and Impudence (1839), the contrast between a stately Bloodhound and a cheeky West Highland Terrier provides a humorous commentary on character types. Through such works, Landseer used animals to explore human virtues, vices, and social structures, making his paintings relatable and thought-provoking for a wide audience.

Masterpieces and Signature Works

Landseer's prolific career yielded numerous celebrated paintings, many of which became deeply ingrained in British visual culture. Among the most famous is The Monarch of the Glen (c. 1851). This majestic portrayal of a red deer stag, set against a misty Highland backdrop, is arguably his most iconic work. It captures a sense of untamed nobility and the sublime power of nature, becoming a symbol of Scotland itself. The painting showcases Landseer's mastery of animal anatomy and his ability to create a truly imposing and memorable image.

Another incredibly popular work was Saved (exhibited 1856), depicting a large Newfoundland dog having rescued a child from drowning, standing watchfully over the small figure on the shore. This painting tapped directly into Victorian sentiments about heroism, loyalty, and the perceived innate goodness of certain animals, particularly dogs associated with rescue like the Newfoundland. Its emotional impact was immense, and it became one of the most frequently reproduced images of the era.

The Old Shepherd's Chief Mourner (exhibited 1837) is a poignant example of Landseer's ability to convey deep emotion through animal portrayal. The painting shows a collie resting its head on its deceased master's coffin in a humble cottage. The dog's posture and expression evoke a profound sense of grief and loyalty, creating a powerful narrative of loss and devotion that resonated strongly with viewers. It exemplifies the sentimental strain in his work that was both highly praised and, later, sometimes criticized.

Other significant works include High Life and Low Life (1829), contrasting the worlds of an aristocratic deerhound and a working-class bulldog mix; Shoeing (exhibited 1844), a detailed and atmospheric scene centered on a farrier shoeing a nervous bay mare, admired for its realism and observation of equine behavior; and Man Proposes, God Disposes (1864), a chilling late work depicting polar bears scavenging the wreckage of Sir John Franklin's lost Arctic expedition, reflecting a darker, more tragic sensibility that emerged in his later years.

Beyond the Canvas: Landseer the Sculptor

While primarily known as a painter, Landseer also made significant contributions as a sculptor. His most famous and publicly visible works in this medium are the four colossal bronze lions guarding the base of Nelson's Column in London's Trafalgar Square. Commissioned in 1858, the project was fraught with delays, partly due to Landseer's meticulous approach and perhaps his declining health, but also due to difficulties in obtaining suitable casts of lions to work from.

Landseer reportedly studied lions extensively at the London Zoo and even obtained a deceased lion to dissect, applying the same rigorous anatomical investigation he used in his painting. He worked closely with the sculptor Carlo Marochetti, who assisted with the casting process. The lions were finally installed in 1867, nearly a decade after the commission began. Despite the protracted creation, the sculptures were widely acclaimed upon completion.

These four lions, each slightly different in pose but unified in their imposing, watchful presence, have become enduring symbols of London and British imperial power. They demonstrate Landseer's ability to translate his understanding of animal form and character into three dimensions on a monumental scale. While his sculptural output was limited compared to his painting, the Trafalgar Square lions remain a major part of his artistic legacy and a testament to his versatility.

Royal Patronage and Esteemed Social Circles

A crucial factor in Landseer's success and fame was his close relationship with the British monarchy. Queen Victoria and her consort, Prince Albert, were enthusiastic admirers and patrons of his work. Starting in the late 1830s, Landseer received numerous commissions from the royal couple. He painted portraits of Victoria and Albert, their children, and, perhaps most famously, their beloved pets. Works like Windsor Castle in Modern Times (1841-45), featuring the Queen, Prince Albert, and the Princess Royal with several dogs, offered intimate glimpses into royal domestic life.

Landseer taught Queen Victoria and Prince Albert etching, further cementing his connection to the royal household. His depictions of their Highland life at Balmoral Castle, often featuring deer and ponies, helped popularize the romantic image of Scotland. This royal favour significantly enhanced Landseer's prestige and social standing. In 1850, Queen Victoria conferred a knighthood upon him, making him Sir Edwin Landseer. He reportedly declined the presidency of the Royal Academy in 1866, possibly due to his health issues.

Beyond royalty, Landseer moved in prominent artistic and literary circles. He was friends with major literary figures such as Charles Dickens and Robert Browning. His interest in spiritualism, a popular movement in the Victorian era, also connected him with various contemporary thinkers and enthusiasts. Within the art world, he was naturally acquainted with the leading figures of his day through the Royal Academy, including the towering landscape painters J.M.W. Turner and John Constable, the popular narrative painter William Powell Frith, and later figures like the Pre-Raphaelites John Everett Millais, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and William Holman Hunt, as well as future RA presidents like Frederic Leighton and the symbolist G.F. Watts. His interactions, collaborations, and friendships formed a rich network within the cultural elite of Victorian Britain.

Artistic Collaborations and Family Ties

Landseer's artistic practice was not solely an individual endeavor. He occasionally collaborated with other artists, most notably the landscape painter Frederick Richard Lee. In these collaborations, Lee would typically paint the landscape settings, while Landseer would add the animals, combining their respective strengths to create harmonious compositions. These joint works further broadened Landseer's reach and demonstrated his ability to work effectively with peers.

However, perhaps the most significant collaboration was with his own family, particularly his elder brother, Thomas Landseer. Thomas was a highly skilled engraver who translated many of Edwin's most popular paintings into prints. This was crucial for disseminating Edwin's work to a much wider audience than could ever see the original paintings. The availability of affordable engravings allowed middle-class families to own copies of Landseer's art, decorating their homes with images like The Monarch of the Glen or Dignity and Impudence. This widespread reproduction cemented Landseer's status as a household name and contributed significantly to his immense popularity.

The artistic inclinations of his other brothers, Charles (a painter of historical subjects) and Arthur Ernest (a lesser-known artist), reinforced the Landseer family's deep involvement in the London art world. Edwin's close friendship with William Hering, who served as his family doctor, also points to the interconnectedness of his professional and personal life within the London society of his time.

Technique, Style Evolution, and Critical Reception

Landseer's technical mastery was evident from early in his career. His draughtsmanship was superb, underpinned by his deep knowledge of anatomy. He handled oil paint with fluency, adept at rendering textures – the softness of fur, the sleekness of a horse's coat, the rough hide of a stag. His use of light and shadow created dramatic effects and highlighted the forms of his subjects. He was also noted for his skill with pencil and chalk, sometimes using white chalk highlights on darker paper to achieve striking results, as seen in studies like the one possibly titled Christ on the Cross.

His style, while rooted in realism, evolved over his career. Early works emphasized anatomical accuracy and sometimes depicted scenes of animal combat or hunting with vigorous energy. As he matured, the sentimental and narrative elements became more pronounced. His depictions of animals often carried clear moral or emotional messages, aligning with Victorian tastes for art that instructed or evoked pathos. This anthropomorphic tendency reached its peak in his mid-career works.

While immensely popular during his lifetime, this very sentimentality led to criticism, particularly in the later 19th and early 20th centuries, as artistic tastes shifted towards Modernism, which often rejected Victorian narrative and emotion. Critics sometimes dismissed his work as overly anecdotal or mawkish. However, there has been a more recent reappraisal of Landseer's art, recognizing his exceptional technical skill, his importance within the context of Victorian culture, and the genuine power of his best works. His ability to connect with audiences on an emotional level, combined with his observational acuity, remains undeniable.

Wider Impact and Enduring Popularity

The impact of Sir Edwin Landseer on British art and culture was profound. His popularity transcended social class, making him one of the first British artists to achieve widespread fame across society, largely thanks to the engravings produced by his brother Thomas. His images became ubiquitous, appearing not only in homes but also used in advertising and popular illustration, demonstrating their broad cultural resonance.

His focus on animals, particularly dogs, contributed to the growing affection for pets and interest in animal welfare during the Victorian era. Works like The Poor Dog (1829) or A Distinguished Member of the Humane Society (1831, another Newfoundland portrait) could be seen as implicitly supporting movements for animal rights by portraying animals with dignity and relatable emotions. His depictions of the Scottish Highlands also played a significant role in shaping the romantic perception of Scotland, influencing tourism and cultural identity.

Today, Landseer's works are held in major public collections across the UK and internationally, including Tate Britain, the Victoria and Albert Museum, the National Gallery of Scotland, the Wallace Collection, and Kenwood House. Exhibitions of his work continue to draw public interest, indicating the enduring appeal of his subjects and his skill. While critical opinions may fluctuate, the recognizability and cultural significance of works like The Monarch of the Glen and the Trafalgar lions ensure his lasting legacy.

Later Life and Mental Health Challenges

Despite his enormous success and public adulation, Landseer's later life was increasingly troubled by ill health and severe mental distress. From the 1840s onwards, he suffered recurring bouts of what contemporaries described as melancholy, anxiety, and paranoia – likely corresponding to modern diagnoses of depression and possibly bipolar disorder. These struggles were reportedly exacerbated by alcohol and perhaps drug use, potentially including substances common in Victorian medicine.

His mental health significantly impacted his ability to work consistently in his later years. While he continued to produce powerful paintings, some, like Man Proposes, God Disposes, reflect a darker, more somber mood. His condition deteriorated markedly in the late 1860s and early 1870s. In 1872, his family had him declared legally insane.

Sir Edwin Landseer died on October 1, 1873. His funeral was a major public event, reflecting his national stature. He was buried with high honours in St Paul's Cathedral, London, a resting place reserved for Britain's most esteemed figures. His death marked the end of an era in British art, concluding a career that had profoundly shaped and reflected the tastes of the Victorian age.

Legacy and Art Historical Assessment

Sir Edwin Landseer occupies a significant and somewhat unique position in British art history. He was undoubtedly the preeminent animal painter of his time, elevating the genre through his technical skill, narrative depth, and emotional insight. His ability to capture the "character" of animals, combined with his anthropomorphic tendencies, struck a powerful chord with the Victorian public, making him one of the most successful and beloved artists of the era.

His influence extended beyond painting; his Trafalgar Square lions remain iconic public sculptures, and his popularization of Scottish Highland imagery had lasting cultural effects. The widespread dissemination of his work through engravings made him a household name and demonstrated the growing power of mass media in the art world. He successfully navigated the highest levels of society, securing royal patronage and achieving immense fame and fortune.

While his reputation suffered somewhat in the face of Modernist critiques of Victorian sentimentality, contemporary assessments often take a more nuanced view. Art historians now recognize his exceptional talent, his role in reflecting and shaping Victorian culture, and the enduring power of his best works. He remains a key figure for understanding 19th-century British art, popular taste, and the complex relationship between humans and the animal kingdom. His burial in St Paul's Cathedral underscores the immense esteem in which he was held by his nation.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision

Sir Edwin Henry Landseer's career was one of extraordinary achievement. From child prodigy to knighted Royal Academician and favourite of the Queen, he dominated the field of animal painting in Britain for decades. His work, characterized by technical brilliance, anatomical accuracy, and a unique ability to imbue animals with emotion and narrative significance, captured the imagination of the Victorian public like few others. Whether depicting the noble stag, the loyal dog, or the majestic lion, Landseer created images that became icons of British art. Despite personal struggles and shifting critical fortunes, his legacy endures through his powerful paintings and sculptures, securing his place as a pivotal figure in the history of art.