Bartolomeo Pedon stands as a fascinating, albeit somewhat enigmatic, figure within the rich tapestry of the Venetian School of painting. Active during the late Baroque period, his life spanned from 1665 to 1733, a correction from the sometimes cited end date of 1732. Born in the heart of Venice, Pedon dedicated his artistic career primarily to landscape painting, developing a style noted for its dynamism, poetic sensibility, and masterful handling of light and color. Though perhaps less universally recognized than some of his Venetian contemporaries, his work represents a significant contribution to landscape art, embodying a transition towards a more expressive and imaginative depiction of nature that foreshadowed elements of Romanticism.

Venetian Roots and Artistic Milieu

Born in Venice in 1665, Bartolomeo Pedon emerged during a period when the city, despite its waning political power, remained a vibrant center for the arts. The unique environment of Venice, with its interplay of water, light, and architecture, had long fostered a distinct artistic tradition emphasizing color (colorito) and atmosphere. Painters like Titian, Tintoretto, and Veronese had established a legacy of visual splendor centuries earlier. By the late 17th and early 18th centuries, while grand history painting continued, landscape and view painting (veduta) were gaining increasing prominence and independence as genres.

Details about Pedon's specific training remain scarce in historical records. However, it is certain that he absorbed the artistic currents of his native city. He would have been exposed to the works of earlier Venetian masters and the developing trends in landscape depiction. His formation undoubtedly took place within the workshops and artistic circles of Venice, where the legacy of rich color and atmospheric effects was deeply ingrained.

The Distinctive Style of Pedon

Bartolomeo Pedon developed a highly individualistic approach to landscape painting. His style is characterized by several key elements that distinguish his work. He employed a notably free and dynamic brushstroke, imbuing his scenes with a sense of energy and movement. This technique moved away from the tighter, more detailed finish often seen in earlier landscapes, leaning towards a more suggestive and expressive rendering.

Color is central to Pedon's art. He utilized a rich palette, often favoring dramatic greens in his landscapes, handled with finesse to create depth and vibrancy. His application of color was not merely descriptive but also emotional, contributing significantly to the overall mood of his paintings. He possessed a keen sensitivity to the effects of light and shadow, using chiaroscuro not just for modeling forms but also for creating dramatic, atmospheric, and often poetic effects. His landscapes frequently possess a strong sense of rhythm and a unique imaginative quality.

Sources suggest Pedon's style reflects influences from various quarters. He was deeply indebted to the work of his slightly older contemporary, the influential Venetian landscape painter Marco Ricci. The impact of Northern European landscape traditions, possibly filtered through prints or visiting artists, can also be discerned, perhaps in a certain naturalism or attention to atmospheric detail. The broader Baroque taste for drama and dynamism certainly informs his compositions. One source even mentions an influence from a "Pietro Cavallieri," though the identity of this figure in relation to Pedon remains somewhat unclear in art historical scholarship and might refer to a lesser-known figure or potentially be a misattribution in the source material itself. Regardless of specific lineages, Pedon synthesized these influences into a personal style marked by originality and a profound understanding of natural phenomena.

Nature's Theatre: Themes and Subjects

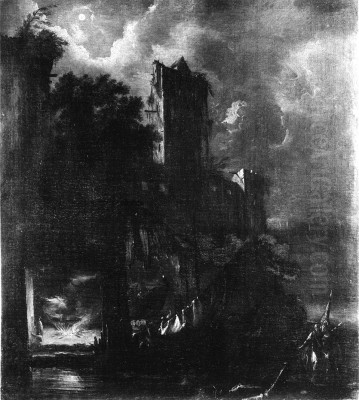

Pedon's primary focus was the natural world. He excelled in depicting various aspects of landscape and seascape, including rivers winding through valleys, coastal scenes, and the expansive ocean. His works often convey a deep appreciation for the power and beauty of nature, sometimes depicting tranquil scenes, other times capturing more dramatic moments, possibly involving storms or evocative night settings.

While nature was his main stage, Pedon frequently integrated figures into his landscapes. These figures, often small in scale compared to their surroundings, could be drawn from religious narratives, mythology, or everyday life. Their inclusion serves not only to provide a focal point or narrative element but also to emphasize the grandeur and sometimes overwhelming presence of the natural environment. This approach aligns with a developing sensibility where the landscape itself becomes a primary vehicle for emotional and poetic expression.

He was recognized for his unique creativity and profound understanding of natural behavior, setting him apart from many contemporaries. His ability to translate the visual experience of nature into paintings filled with imagination and poetic feeling was a hallmark of his achievement. Furthermore, while celebrated for landscapes, some accounts suggest he also possessed considerable talent in still life painting, showcasing a broader artistic range.

Representative Works

Several key works exemplify Bartolomeo Pedon's artistic vision and skill. Among his most noted paintings is Cretans on the Road to Emmaus. This work, currently housed in the Zavičajni Muzej Grada Rovinja in Rovinj, Croatia, depicts figures identified as Cretans journeying along a path set within a dramatic landscape featuring a deep valley and a river. Significantly, the scene incorporates the biblical episode of the resurrected Christ appearing to two disciples on the road to Emmaus, with angelic figures also present. The painting masterfully blends religious narrative with an evocative landscape setting, showcasing Pedon's ability to use nature as a powerful backdrop for storytelling.

Another significant work often cited is simply titled Paesaggio (Landscape), located in the Museo Civico di Padova in Padua. While the specific subject may be a more generalized landscape, it is representative of his style, likely characterized by the dramatic use of green tones and striking light effects that historical sources praise in his work. Such paintings highlight his focus on capturing the atmosphere and visual poetry of the natural world.

Mention is also made of a work depicting Genesis, noted for its strong dynamism and attention to natural detail. This suggests Pedon tackled fundamental biblical themes, interpreting them through his distinctive landscape lens, emphasizing the elemental forces and burgeoning life inherent in the creation story. These examples underscore his capacity for rendering both specific narratives and broader natural vistas with artistic conviction.

Pedon in the Context of Venetian Art

Understanding Pedon requires placing him within the vibrant artistic milieu of late 17th and early 18th-century Venice. His work resonates strongly with that of Marco Ricci (1676-1730), who is often cited as a primary influence. Both artists were pioneers in developing a more expressive and atmospheric style of landscape painting in Venice, moving beyond purely topographical representation. Comparing Pedon to Ricci reveals shared interests but also individual temperaments in their handling of paint and composition.

Pedon's career also overlapped with Marco's uncle, the celebrated history painter Sebastiano Ricci (1659-1734), whose international success contributed to the prestige of Venetian art during this period. While their primary genres differed, they were part of the same artistic generation revitalizing Venetian painting.

A comparison provided in the source material contrasts Pedon with Francesco Alotto (or Alalto, the name seems slightly uncertain in the source). While both were influenced by the Venetian school, their styles diverged. Pedon favored dynamic brushwork, strong light contrasts, and a romantic, naturalistic approach, often focusing on wilder landscapes or religious themes within nature. Alotto, known for works like a Panoramic View of the Grand Canal, reportedly employed a more detailed, perhaps more realistic technique with subtler color variations, often focusing on urban views (vedute). This comparison highlights the diversity within Venetian painting, even among contemporaries.

Pedon worked alongside other notable Venetian artists. Luca Carlevarijs (1663-1730) was an important early figure in Venetian view painting, setting the stage for later masters. Although Pedon's focus was generally less topographical, he shared the era's growing interest in depicting specific locales or types of environments. His work offers a more imaginative counterpoint to the precise vedute that would later be perfected by Canaletto (Giovanni Antonio Canal, 1697-1768) and imbued with atmospheric poetry by Francesco Guardi (1712-1793).

The period also saw the flourishing of artists in other genres, such as the celebrated pastel portraitist Rosalba Carriera (1675-1757) and the dominant figure of grand decorative painting, Giambattista Tiepolo (1696-1770). Their presence underscores the richness and variety of the Venetian art scene during Pedon's lifetime. Later landscape painters like Francesco Zuccarelli (1702-1788), who was also influenced by Marco Ricci, would continue to develop the pastoral and picturesque landscape traditions in Venice. Pedon's work can be seen as part of this broader evolution of landscape painting within the Venetian context, influenced by figures like Claude Lorrain (1600-1682) from the Franco-Roman school and perhaps even the wilder, more dramatic landscapes of Salvator Rosa (1615-1673), whose works were influential throughout Italy.

An Act of Destruction: The Lost Secular Works

An intriguing, though possibly slightly misreported, anecdote surrounds Bartolomeo Pedon's relationship with his own creations. Historical accounts, as relayed by the source material, mention that he personally destroyed many of his earlier, secular works. The source initially places this event in the "early 1500s," which is chronologically impossible given Pedon's lifespan (1665-1733). This act must have occurred sometime during his mature career, likely in the late 17th or, more probably, the early 18th century.

The reasons behind this purported act of destruction remain speculative. It could have stemmed from a period of intense religious piety, leading him to renounce or devalue his non-religious creations. Alternatively, it might have been driven by artistic self-criticism, a desire to erase works he no longer felt represented his mature style or standards. Whatever the motivation, this reported event resulted in the unfortunate permanent loss of a portion of his oeuvre, particularly potentially limiting our understanding of his engagement with purely secular themes in his earlier years. This act adds a layer of personal drama to his biography and highlights the complex relationship artists can have with their own legacy.

Legacy and Historical Assessment

Bartolomeo Pedon's contribution to art history lies primarily in his role within the development of Venetian landscape painting. He is recognized by art historians as one of the more artistically significant and individualistic painters of his generation within the Venetian school, particularly praised for his ability to capture the dynamics of nature and the evocative qualities of light. Scholars like Grgo Gamulin have noted the strong sense of rhythm and the powerful light-shadow contrasts in his work, indicative of a unique compositional and expressive strength.

His work contributed to the diversification of artistic styles in Venice, offering a more imaginative and emotionally charged approach to landscape compared to the burgeoning veduta tradition. He successfully fused religious and mythological themes with deeply felt depictions of the natural world, reflecting perhaps the broader Baroque integration of spirituality and dramatic representation, possibly even responding to the artistic climate shaped by the Counter-Reformation's emphasis on affecting religious imagery.

Despite these qualities, Pedon has not achieved the same level of widespread fame as some contemporaries like Canaletto or Guardi. Modern scholarship acknowledges his importance but also notes his relative obscurity. This has been attributed partly to the potential loss of works (including the self-destroyed pieces) and perhaps a historical lack of focused, in-depth academic study dedicated solely to him.

However, recent decades have seen growing scholarly interest in Pedon. His name and works appear more frequently in studies of Venetian Baroque and Rococo painting, and his role as a key figure in the landscape genre, particularly as a follower and interpreter of Marco Ricci's innovations, is increasingly appreciated. He is valued for his originality, his technical skill, and his contribution to a more poetic and pre-Romantic vision of landscape.

Conclusion

Bartolomeo Pedon (1665-1733) remains a compelling figure in Venetian art history. As a master of landscape painting, he carved out a distinct niche with his dynamic brushwork, rich color palette, dramatic use of light, and profoundly poetic imagination. Deeply rooted in the Venetian tradition yet open to broader European influences, particularly the innovations of Marco Ricci, he created works that capture the theatre and emotion of the natural world. His surviving paintings, such as Cretans on the Road to Emmaus and various Paesaggi, stand as testaments to his unique vision. While perhaps historically overshadowed by painters with larger surviving outputs or more focused scholarly attention, Pedon's art offers a significant glimpse into the evolution of landscape painting, embodying a bridge between the Baroque era's dynamism and the burgeoning expressive sensibilities that would later flourish in Romanticism. He remains an important artist whose evocative landscapes continue to reward study and appreciation.