Gioacchino Assereto, a prominent figure of the Genoese School during the Baroque period, remains a compelling artist whose works are characterized by their dramatic intensity, vigorous brushwork, and profound psychological depth. Though perhaps not as universally recognized as some of his Italian contemporaries, Assereto carved a unique niche for himself, contributing significantly to the vibrant artistic landscape of 17th-century Genoa. His paintings, often depicting religious and mythological scenes, resonate with an emotional power and a raw naturalism that continue to captivate art lovers and scholars alike.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Genoa

Gioacchino Assereto was born in Genoa, a bustling maritime republic with a rich artistic heritage. The precise date of his birth was for some time a subject of minor debate among scholars, but it is now firmly established as 1600. He was baptized on October 18, 1600, in the church of San Salvatore, which helps confirm this year. His artistic journey began at a young age. According to early biographers, notably Raffaele Soprani in his "Le vite de' pittori, scultori, ed architetti genovesi," Assereto was apprenticed around the age of 12, circa 1612, to the painter Luciano Borzone.

Borzone was a respected artist in Genoa, known for his narrative clarity and a style that was beginning to absorb the new naturalistic tendencies filtering into the city. Assereto's time with Borzone would have provided him with a solid foundation in drawing and painting techniques. However, his ambition and talent soon led him to seek further instruction.

Around 1614, he moved to the workshop of Giovanni Andrea Ansaldo, another leading Genoese painter of the era. Ansaldo was known for his large-scale decorative frescoes and altarpieces, and his workshop was a hub of artistic activity. Under Ansaldo, Assereto would have been exposed to a broader range of commissions and a more dynamic, compositionally complex style. It is believed that Assereto remained with Ansaldo for a significant period, likely until the mid-1620s, contributing to workshop projects and honing his own burgeoning style. His early works from this period, though difficult to pinpoint with absolute certainty, likely show the influence of both his masters.

The Vibrant Artistic Milieu of Genoa

To understand Assereto's development, it's crucial to appreciate the artistic environment of Genoa during the early 17th century. Genoa was a wealthy city, its prosperity fueled by banking and maritime trade. This wealth attracted artists from other parts of Italy and Europe, creating a dynamic and cosmopolitan art scene. The city's patrons, including noble families like the Doria, Spinola, and Balbi, as well as religious orders, were eager to commission works that would display their piety and status.

The influence of Caravaggio, though he never worked in Genoa, was palpable, largely disseminated through the works of his followers (the Caravaggisti) and through copies of his paintings. Artists like Orazio Gentileschi and Simon Vouet spent time in Genoa, bringing with them their interpretations of Caravaggio's revolutionary naturalism and dramatic use of light (tenebrism). Furthermore, the presence of Flemish masters such as Peter Paul Rubens and Anthony van Dyck in Genoa during the 1620s introduced a new level of painterly richness, vibrant color, and dynamic composition that left an indelible mark on local artists.

Genoese painters like Bernardo Strozzi, a contemporary of Assereto, were already forging a distinctive local style that blended Lombard naturalism with Venetian color and Flemish exuberance. Other notable Genoese artists active during or slightly after Assereto's formative years included Domenico Fiasella, known as "Il Sarzana," and later figures like Giovanni Benedetto Castiglione (Il Grechetto) and Valerio Castello, who would further develop the Genoese Baroque. Assereto emerged within this fertile ground, absorbing various influences while cultivating his own powerful and individual artistic voice.

Assereto's Developing Style: Tenebrism and Dramatic Narrative

Assereto's mature style is characterized by its dramatic use of chiaroscuro, a technique involving strong contrasts between light and dark. This tenebrism, while reminiscent of Caravaggio, is employed by Assereto with a unique Genoese sensibility. His figures are often robust and earthy, rendered with a vigorous, almost urgent brushwork that imbues them with a palpable sense of life and movement. He was particularly adept at capturing moments of intense emotion and psychological drama, drawing the viewer directly into the narrative.

His compositions are often dynamic, with figures arranged in complex, sometimes crowded, groupings. He favored close-up perspectives that heighten the immediacy of the scene. Unlike the polished surfaces of some Caravaggisti, Assereto's paint application can be quite painterly and expressive, with visible brushstrokes contributing to the overall texture and energy of the work. His palette, especially in his earlier and middle periods, often relies on warm, earthy tones – browns, ochres, and deep reds – punctuated by strategic highlights.

There is a certain raw, unidealized quality to many of Assereto's figures. They are not always classically beautiful but are instead imbued with a rugged realism that makes their suffering, piety, or surprise all the more convincing. This focus on authentic human experience, conveyed through powerful gesture and expression, is a hallmark of his art.

Key Themes and Iconography in Assereto's Oeuvre

Assereto's subject matter was typical of the Baroque period, encompassing a wide range of religious scenes, mythological narratives, and historical episodes. He was particularly drawn to themes that allowed for the depiction of intense human emotion and dramatic action.

Old Testament stories were a frequent source of inspiration. Works such as Moses Striking the Rock (Prado Museum, Madrid), The Finding of Moses (Palazzo Bianco, Genoa), and David with the Head of Goliath (various versions, including one in a private collection) showcase his ability to render epic narratives with a sense of immediacy and human drama. The raw power of these scenes is often amplified by his use of tenebrism and the expressive faces of his protagonists.

New Testament scenes also feature prominently in his work. Christ Healing the Blind Man (Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, and another version in the National Gallery of Slovenia) is a recurring theme, allowing Assereto to explore compassion and divine power. His depictions of the Passion of Christ, such as Ecce Homo (Palazzo Bianco, Genoa), are particularly moving, conveying Christ's suffering with profound empathy. The Angel Appearing to Hagar and Ishmael (Palazzo Rosso, Genoa) is another notable example, capturing a moment of divine intervention and human despair with great sensitivity.

Mythological and historical subjects also provided Assereto with opportunities for dramatic storytelling. The Death of Cato (Palazzo Bianco, Genoa) is a powerful depiction of the Stoic philosopher's suicide, rendered with a stark realism and emotional intensity that is characteristic of the artist. He also painted scenes from Roman history and classical mythology, often choosing moments of high drama or moral significance.

Analysis of Major and Representative Works

To fully appreciate Assereto's artistry, it is instructive to examine some of his key paintings:

_The Death of Cato_ (c. 1640s, Palazzo Bianco, Genoa): This is arguably one of Assereto's most famous and powerful works. It depicts Cato the Younger, a Roman statesman, committing suicide rather than submit to Julius Caesar. Assereto presents the scene with unflinching realism. Cato is shown in his final moments, his face contorted in pain, his hand thrust into his own wound. The dramatic lighting focuses on Cato's pale torso and the bloodied sheets, while the surrounding darkness heightens the sense of tragedy. The raw emotion and visceral impact of this painting are hallmarks of Assereto's mature style.

_Moses Striking the Rock_ (c. 1640, Museo del Prado, Madrid): This large canvas illustrates the biblical story where Moses miraculously brings forth water from a rock to quench the thirst of the Israelites in the desert. Assereto fills the composition with a multitude of figures, their expressions and gestures conveying their desperation and then their relief. Moses, at the center, is a commanding figure, his divine authority evident. The painting showcases Assereto's skill in handling complex multi-figure compositions and his ability to create a sense of dynamic movement and collective emotion. The earthy palette and strong chiaroscuro are typical of his style.

_The Angel Appearing to Hagar and Ishmael_ (c. 1640s, Palazzo Rosso, Genoa): This painting depicts the poignant Old Testament story of Hagar and her son Ishmael, cast out into the wilderness and on the verge of death from thirst, when an angel appears to show them a well. Assereto captures the despair of Hagar and the exhaustion of Ishmael with great empathy. The angel's intervention is a moment of dramatic revelation, illuminated by a divine light. The emotional intensity of the scene is palpable, conveyed through the figures' expressive postures and faces.

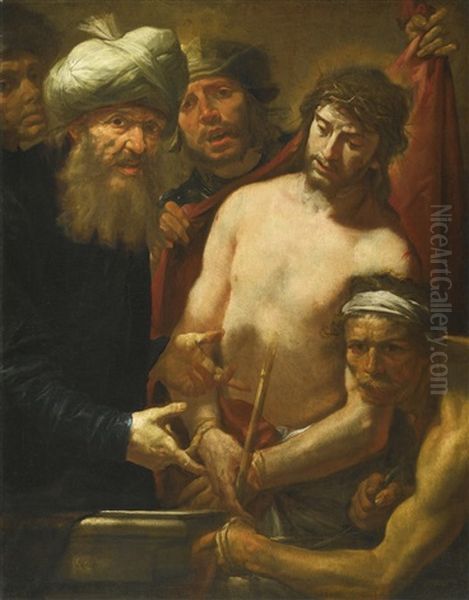

_Ecce Homo_ (c. 1630s, Palazzo Bianco, Genoa): In this depiction of Christ presented to the crowd by Pontius Pilate, Assereto focuses on the suffering and dignity of Christ. The close-up framing and dramatic lighting emphasize Christ's tormented face and bound hands. The surrounding figures, including Pilate and the soldiers, are rendered with a characteristic realism. The painting is a powerful meditation on sacrifice and injustice, delivered with Assereto's typical emotional force.

_Tobias Healing his Father's Blindness_ (c. 1640, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Marseille): This work illustrates another popular Baroque theme, the story of Tobias anointing his father Tobit's eyes with fish gall to restore his sight, guided by the Archangel Raphael. Assereto masterfully conveys the tender intimacy of the moment, the hope and anticipation on the faces of the family members, and the serene presence of the angel. The interplay of light and shadow enhances the emotional depth of the scene.

These examples, among many others like Saint Augustine and Saint Monica (private collection) or The Supper at Emmaus (Boijmans Van Beuningen Museum, Rotterdam), demonstrate Assereto's consistent ability to infuse traditional subjects with a fresh and compelling psychological realism.

Influences and Connections: Caravaggism and Beyond

The question of Assereto's relationship with Caravaggism is central to understanding his art. While he was not a direct pupil of Caravaggio (Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio), the impact of Caravaggio's revolutionary style is undeniable in Assereto's work. The dramatic use of tenebrism, the unidealized depiction of figures, and the focus on moments of intense human drama all echo Caravaggio's innovations.

However, Assereto was not a mere imitator. He absorbed Caravaggesque principles and adapted them to his own artistic temperament and the specific context of Genoese painting. His brushwork is often looser and more gestural than that of many Roman Caravaggisti like Bartolomeo Manfredi or the French Valentin de Boulogne. His figures, while realistic, often possess a particular Genoese robustness and earthiness.

The presence of Orazio Gentileschi in Genoa from 1621 to 1623, and Simon Vouet from 1620 to 1621, provided more direct exposure to Caravaggesque ideas. Gentileschi, in particular, offered a more lyrical and refined interpretation of Caravaggio's style, which may have influenced Assereto's handling of light and color in certain phases.

Beyond Caravaggism, Assereto was also receptive to other artistic currents. The influence of Lombard painters, such as Giulio Cesare Procaccini, who also worked in Genoa, can be seen in the emotional intensity and sometimes agitated movement of his figures. Furthermore, the brief but impactful visits of Peter Paul Rubens (1604-1608, with return visits) and Anthony van Dyck (1621-1627) to Genoa introduced a new dynamism, richness of color, and painterly bravura that resonated with many Genoese artists, including Assereto. While Assereto's palette generally remained more subdued and earthy than that of Rubens or Van Dyck, some of his later works show a greater fluidity and a brighter range of colors, possibly reflecting these Flemish influences.

His Genoese contemporaries, such as the prolific Bernardo Strozzi, also played a role in shaping the local artistic environment. Strozzi, with his rich impasto and vibrant color, offered another model of Baroque dynamism. While their styles differed, both artists contributed to the distinctive character of Genoese Baroque painting.

Later Career, Mature Style, and Untimely Death

Assereto's career progressed steadily, and he received numerous commissions for altarpieces, private devotional paintings, and narrative scenes. He established his own workshop and had pupils, including his son Giuseppe Assereto, who continued to work in a similar style.

His mature style, developed from the late 1630s until his death, represents the culmination of his artistic development. During this period, his compositions often became more complex, his figures more monumental, and his handling of paint even more confident and expressive. He continued to explore themes of intense emotion and human drama, but with an increasing mastery of his medium. Some scholars suggest a possible brief trip to Rome around 1639, which, if it occurred, might have further exposed him to the latest developments in Roman Baroque painting, including the classicism of artists like Andrea Sacchi or the High Baroque exuberance of Pietro da Cortona. However, concrete evidence for such a trip remains elusive, and his style remained fundamentally rooted in his Genoese origins and his personal interpretation of tenebrism.

Tragically, Gioacchino Assereto's promising career was cut short. He died in Genoa on June 28, 1649, at the relatively young age of 49. The cause of his death is not definitively known, but his passing represented a significant loss for the Genoese art world. Had he lived longer, he might have achieved even greater recognition and further evolved his powerful style.

Anecdotes, Controversies, and Artistic Persona

Unlike some of his more flamboyant contemporaries, Assereto's life seems to have been relatively free of major public controversies or scandalous anecdotes, at least as recorded by early biographers like Soprani. Soprani describes him as a diligent and hardworking artist, dedicated to his craft. The primary "controversy," if one can call it that, in Assereto scholarship often revolves around attributions and the precise dating of his works, given the scarcity of signed or dated pieces and the activity of his workshop and followers.

His artistic persona, as gleaned from his paintings, is that of a deeply empathetic observer of the human condition. He was not afraid to depict suffering, ugliness, or intense emotion, but he did so with a profound sense of humanity. There is an honesty and directness in his art that transcends mere technical skill.

One aspect that sometimes arises in discussions is the perceived "roughness" or lack of polish in some of his works. This, however, is generally understood not as a lack of ability but as a deliberate stylistic choice, contributing to the raw energy and expressive power of his paintings. His vigorous, visible brushwork was a means of conveying immediacy and emotional intensity, a departure from the more finished surfaces favored by some other schools of painting.

Technique and Materiality

Assereto's technique is characterized by its directness and expressiveness. He typically worked with oil on canvas, often on a relatively coarse weave, which could contribute to the textured surface of his paintings. His preparatory methods likely involved preliminary sketches, but the final execution often appears rapid and confident, with bold brushstrokes defining form and conveying movement.

His use of chiaroscuro was fundamental. He would build up his compositions with strong contrasts, using deep shadows to create a sense of volume and drama, and strategically placed highlights to draw attention to key figures or emotional focal points. His figures are often solidly modeled, with a strong sense of three-dimensionality.

The palette, as mentioned, leaned towards earthy tones, particularly in his earlier and middle periods: ochres, browns, deep reds, and umbers. These were often enlivened by touches of brighter color, such as blues or whites, especially in draperies or celestial elements. In some later works, there is evidence of a slightly brighter and more varied palette, possibly reflecting broader European influences.

The materiality of his paint is often evident. He was not afraid to leave his brushwork visible, and this painterly quality contributes to the vitality and immediacy of his art. This approach aligns with a broader Baroque interest in sprezzatura (a sense of effortless mastery) and a move away from the highly polished finish of Renaissance painting.

Gioacchino Assereto's Art Market Performance and Collection Distribution

For many years, Gioacchino Assereto was somewhat overlooked in the broader art market, often overshadowed by more famous Italian Baroque names or even by his Genoese contemporary Bernardo Strozzi. However, in recent decades, there has been a growing appreciation for his work, leading to increased scholarly attention and a corresponding rise in his market value.

Works by Assereto appear periodically at major auction houses like Sotheby's and Christie's. Prices can vary significantly depending on the size, subject matter, condition, provenance, and overall quality of the piece. Important, well-documented paintings with strong compositions and emotional impact can command significant sums, sometimes reaching into the hundreds of thousands of dollars or euros. Smaller works or those with attribution questions naturally fetch lower prices.

Assereto's paintings are held in numerous prestigious public collections and museums around the world. In Italy, his works are prominently featured in Genoese museums, including the Palazzo Bianco, Palazzo Rosso (both part of the Musei di Strada Nuova), and the Galleria Nazionale di Palazzo Spinola. Other Italian museums, such as the Pinacoteca di Brera in Milan, also hold examples of his art.

Internationally, his paintings can be found in:

Spain: The Museo del Prado in Madrid holds key works like Moses Striking the Rock.

France: The Musée des Beaux-Arts de Marseille has the notable Tobias Healing his Father's Blindness, and the Louvre in Paris also has works attributed to him.

United Kingdom: The National Gallery, London, possesses The Angel Appearing to Hagar and Ishmael.

United States: The Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh (Christ Healing the Blind Man), the Ringling Museum of Art in Sarasota, and other American museums have examples of his work.

Russia: The Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg.

Other European Countries: Museums in Germany, Austria (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna), Slovenia (National Gallery of Slovenia, Ljubljana), and the Netherlands (Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam) also house his paintings.

The distribution of his works across these international collections attests to his significance and the appeal of his dramatic style. Many other pieces remain in private collections, occasionally surfacing in exhibitions or on the art market.

Academic Evaluation and Historical Position

Academic evaluation of Gioacchino Assereto has evolved considerably. Early accounts, such as that by Raffaele Soprani (1768 edition, revised by Carlo Giuseppe Ratti), provided foundational biographical information and recognized his talent. However, for a long period, he, like many Genoese Baroque painters, was somewhat marginalized in broader art historical narratives that tended to focus on Rome, Venice, and Florence.

The 20th century saw a resurgence of interest in Italian Baroque regional schools, including the Genoese. Scholars began to re-evaluate Assereto's contribution, recognizing his unique voice and his role in the development of Genoese painting. Exhibitions dedicated to Genoese Baroque art, both in Italy and internationally, have helped to bring his work to a wider audience and to solidify his reputation.

Art historians today generally regard Assereto as one of the most original and powerful painters of the Genoese School in the first half of the 17th century. He is praised for his dramatic intensity, his psychological insight, his vigorous and expressive brushwork, and his ability to create compelling narrative compositions. While acknowledging the influence of Caravaggism, scholars also emphasize his individuality and his synthesis of various artistic currents into a distinctly personal style.

His position is seen as crucial in the transition from the earlier naturalism inspired by Caravaggio towards a more fully developed Baroque dynamism. He is considered a key figure alongside Bernardo Strozzi and, slightly later, Giovanni Benedetto Castiglione, in defining the character of Genoese painting during its golden age. His relatively short life undoubtedly limited his output and perhaps his broader contemporary fame, but the quality and impact of his surviving works secure his place as a significant master of the Italian Baroque. Ongoing research continues to refine our understanding of his oeuvre, his workshop practices, and his precise relationship with his contemporaries.

Conclusion: The Enduring Power of Assereto's Vision

Gioacchino Assereto stands as a testament to the artistic vitality of 17th-century Genoa. Born in 1600 and dying in 1649, his career, though tragically brief, was marked by a consistent production of emotionally charged and visually compelling paintings. From his early training with Luciano Borzone and Giovanni Andrea Ansaldo to his mature works that synthesized Caravaggesque tenebrism with a uniquely Genoese vigor, Assereto forged a distinctive artistic identity.

His depictions of biblical, mythological, and historical scenes are characterized by their raw naturalism, dramatic lighting, and profound psychological depth. Works like The Death of Cato, Moses Striking the Rock, and The Angel Appearing to Hagar and Ishmael exemplify his ability to capture moments of intense human experience with an unflinching honesty and a powerful, expressive brush.

While influenced by the broader currents of Italian and European Baroque art, including the innovations of Caravaggio and the painterly richness of Flemish masters like Rubens and Van Dyck who visited Genoa, Assereto was no mere follower. He absorbed these influences and reinterpreted them through his own artistic lens, contributing significantly to the distinctive character of the Genoese School alongside contemporaries such as Bernardo Strozzi and Domenico Fiasella.

Today, Assereto's paintings are prized in collections worldwide, and his reputation among scholars and connoisseurs continues to grow. He is recognized not only as a key figure in Genoese art but also as an important contributor to the broader tapestry of Italian Baroque painting. His ability to convey profound emotion and dramatic narrative with such directness and painterly force ensures that the art of Gioacchino Assereto remains as compelling and relevant today as it was in his own time.