Bertha Wegmann stands as a significant, yet for a long time overlooked, figure in the landscape of late 19th and early 20th-century European art. A Danish painter of Swiss origin, her journey through the art worlds of Copenhagen, Munich, and Paris shaped her into a formidable talent, particularly celebrated for her insightful portraits, vibrant landscapes, and delicate still lifes. Wegmann's career was not only a testament to her artistic prowess but also a reflection of the shifting roles and increasing visibility of women in the professional art world. This exploration delves into her life, her artistic evolution, her connections within the art community, and the enduring legacy of her work.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Copenhagen

Born in Soglio, Switzerland, in 1847, Bertha Wegmann's destiny as an artist began to unfold when her family relocated to Copenhagen, Denmark, when she was merely five years old. Her father, a merchant by trade, was also a passionate art enthusiast. Recognizing his daughter's burgeoning interest in drawing and painting from a young age, he became her first informal tutor, nurturing her innate talent. This early encouragement in a supportive home environment was crucial, especially in an era when artistic careers for women were not widely accepted or facilitated.

The Copenhagen of Wegmann's youth was a city with a rich artistic heritage, home to the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, an institution that had shaped generations of Danish Golden Age painters like Christoffer Wilhelm Eckersberg and Christen Købke. However, like many art academies across Europe at the time, it was not yet open to female students. This institutional barrier meant that aspiring women artists had to seek alternative paths for their education, often relying on private tutors or seeking opportunities abroad. Wegmann's early artistic inclinations were thus channeled through these less formal, yet vital, avenues.

Navigating Educational Barriers and Early Training

Despite her evident passion, the doors of the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts remained closed to Bertha Wegmann due to her gender. This was a common plight for women artists of her generation, including contemporaries in other countries like Berthe Morisot and Mary Cassatt in France, who also had to navigate a male-dominated art establishment. Undeterred, Wegmann, with her father's continued support, pursued private instruction.

In Copenhagen, she began her formal artistic education around the age of nineteen, studying under established Danish artists such as Frederik Ferdinand Helsted and Frederik Christian Lund. These painters, working within the Danish academic tradition, would have provided her with a solid grounding in drawing, composition, and the prevailing realistic styles of the period. This foundational training was essential, equipping her with the technical skills that would later allow her to explore more modern artistic expressions. The limitations in her home country, however, spurred a desire to seek more advanced and diverse training elsewhere in Europe.

The Munich Years: Formal Training and New Connections

Seeking to broaden her artistic horizons, Bertha Wegmann made the pivotal decision to move to Munich in the late 1860s. Munich, at that time, was a major European art center, rivaling Paris in its academic offerings and attracting students from across the continent. The Munich School was known for its dark palette, emphasis on realism, and mastery of draftsmanship, with prominent figures like Wilhelm Leibl and Franz von Lenbach influencing its direction.

In Munich, Wegmann enrolled for instruction under Professor Wilhelm von Lindenschmit the Younger, a respected history painter, and later with the genre painter Eduard Kurzbauer. These tutors, steeped in the academic traditions of the Munich School, would have further honed her skills in figure painting and narrative composition. However, Wegmann reportedly found the prevailing academic atmosphere somewhat stifling to her evolving artistic sensibilities.

It was also in Munich that Wegmann formed a crucial and lasting friendship with the Swedish painter Jeanna Bauck. Bauck, who also studied in Munich, became a close companion and artistic confidante. They shared a studio, a common practice for artists seeking mutual support and to defray costs. This period of shared artistic exploration and camaraderie was undoubtedly formative for both women, providing a supportive environment in a field where women often faced isolation. Their professional and personal bond would continue for many years, influencing each other's work and careers.

Paris: The Crucible of Modernism and Salon Success

The allure of Paris, the undisputed capital of the art world in the latter half of the 19th century, eventually drew Bertha Wegmann and Jeanna Bauck. They moved to Paris in 1880 or 1881. The city was a vibrant hub of artistic innovation, the birthplace of Impressionism with artists like Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, and Camille Pissarro revolutionizing painting, and a center for Naturalism, championed by figures such as Jules Bastien-Lepage and Jean-François Millet.

In Paris, Wegmann continued her studies, possibly attending private ateliers or schools that admitted women, such as the Académie Julian or the École de Dessin et Peinture pour Femmes, which attracted many Scandinavian female artists. She immersed herself in the city's dynamic art scene, absorbing the influences of French Naturalism and the lighter palette and looser brushwork of Impressionism. This exposure significantly impacted her style, leading to a brighter, more luminous quality in her work and a greater emphasis on capturing fleeting moments and the effects of light.

Wegmann began exhibiting at the prestigious Paris Salon, the official art exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts. Her talent was quickly recognized. In 1881, exhibiting as "Berthe Vegman," she received an "Mention Honorable" for her Portrait de Mlle Jeanna Bauck. This was a significant achievement, marking her entry into the competitive Parisian art world. The following year, in 1882, she achieved even greater success, winning a gold medal at the Salon, a remarkable feat for any artist, particularly a foreign woman. She continued to exhibit regularly, also receiving a service gold medal in 1892 and silver medals at the Paris Salons of 1889 (during the Exposition Universelle) and 1900. These accolades solidified her reputation as a skilled and respected artist on an international stage. During her time in Paris, she would have been aware of, and potentially interacted with, leading figures like Jean-Léon Gérôme, who represented the academic tradition, and Édouard Manet, a pivotal figure in the transition to modernism.

Artistic Style and Thematic Concerns

Bertha Wegmann's artistic style evolved throughout her career, reflecting her diverse training and the influences she encountered. Initially grounded in the academic realism of her Danish and Munich teachers, her work progressively embraced the lighter palette, looser brushwork, and interest in capturing the effects of light characteristic of French Impressionism and Naturalism.

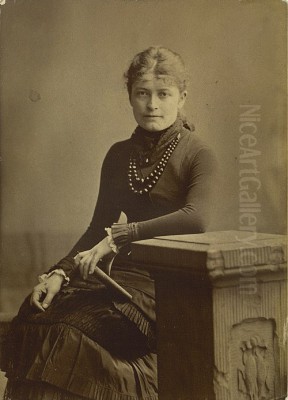

Portraiture was a cornerstone of her oeuvre. Wegmann possessed a remarkable ability to capture not only the likeness but also the personality and inner life of her sitters. Her portraits are often characterized by their psychological depth, sensitivity, and a sense of immediacy. She was particularly adept at portraying women, often depicting them in thoughtful, introspective poses, challenging conventional, more objectified representations. Her Portrait of Jeanna Bauck is a prime example, showcasing a confident, modern woman artist.

Beyond portraits, Wegmann also excelled in landscape painting and still lifes. Her landscapes, such as Port of St. Ives, demonstrate her skill in rendering atmospheric effects and the play of light on water and land, often with a vibrant, impressionistic touch. Her still lifes, like Roses in a Glass Bottle or Interior with a Bouquet of Wildflowers, are celebrated for their delicate beauty, refined color harmonies, and intimate portrayal of everyday objects. These works often reveal a modern sensibility in their composition and handling of paint. Works like Study of a Young Mother with Child in the Garden highlight her ability to capture tender, intimate moments of domestic life with warmth and naturalism.

Key Collaborations and Friendships: The Bond with Jeanna Bauck

The most significant artistic and personal relationship in Bertha Wegmann's life was undoubtedly with the Swedish painter Jeanna Bauck (1840-1926). Their friendship, forged in Munich, extended through their years together in Paris and beyond. They shared studios in both cities, a common practice that fostered mutual support and intellectual exchange. This close collaboration was not merely practical; it was a deep artistic partnership.

Their shared experiences as women navigating the male-dominated art world, and as expatriates in foreign cities, likely strengthened their bond. They painted portraits of each other, a testament to their mutual respect and affection. Wegmann's 1881 Salon-honored Portrait de Mlle Jeanna Bauck depicts Bauck with palette and brushes in hand, confidently gazing at the viewer, an image of a professional artist. Conversely, Bauck also painted Wegmann. These reciprocal portraits offer a fascinating glimpse into their relationship and their identities as working artists.

Their collaboration extended to exploring new artistic territories together, such as outdoor (en plein air) painting, a practice popularized by the Impressionists. The support and critical feedback from a trusted peer like Bauck would have been invaluable for Wegmann's artistic development. While the exact nature of their personal relationship remains a subject of historical interpretation, their profound professional and personal connection is undeniable and stands as a notable example of female artistic solidarity in the 19th century. Beyond Bauck, Wegmann also maintained connections with other artists, including the Danish artist Hildegard Thorell, whom she supported, and Marie Krøyer, who reportedly modeled for her on occasion.

Notable Works and Their Significance

Several works stand out in Bertha Wegmann's oeuvre, illustrating her stylistic range and thematic interests:

_Portrait of Jeanna Bauck_ (1881): This painting is significant not only for the recognition it received at the Paris Salon but also as a powerful representation of a female artist. Wegmann portrays Bauck as a self-assured professional, actively engaged in her craft. The direct gaze and confident posture challenge traditional, more passive depictions of women.

_Port of St. Ives_: This landscape showcases Wegmann's engagement with Impressionistic techniques. The vibrant colors, broken brushwork, and focus on capturing the fleeting effects of light on the Cornish coastal scene demonstrate her mastery of outdoor painting and her ability to convey atmosphere.

_Roses in a Glass Bottle_: A testament to her skill in still life, this work reveals Wegmann's sensitivity to color and texture. The delicate rendering of the roses and the play of light on the glass bottle highlight her observational acuity and her exploration of modernist aesthetics within a traditional genre.

_Study of a Young Mother with Child in the Garden_: This painting exemplifies Wegmann's ability to capture intimate, everyday scenes with warmth and psychological insight. The tender interaction between mother and child is rendered with a naturalism that avoids sentimentality, focusing instead on the quiet emotion of the moment.

_Interior with a Bouquet of Wildflowers_: This work combines elements of still life and interior scenes, showcasing Wegmann's skill in composing harmonious arrangements and her appreciation for the simple beauty of domestic settings and natural elements. The wildflowers suggest an informality and connection to nature that aligns with Impressionist sensibilities.

These works, among many others, demonstrate Wegmann's versatility and her ability to imbue various subjects with her distinctive artistic vision, characterized by technical skill, sensitivity, and a modern outlook.

Return to Denmark and Institutional Recognition

After her successful years in Paris, Bertha Wegmann eventually returned to Denmark, settling in Copenhagen in 1883. Her international reputation preceded her, and she quickly became a prominent figure in the Danish art scene. That same year, 1883, she was awarded the prestigious Thorvaldsen Medal by the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, a high honor recognizing her artistic achievements.

Significantly, Wegmann broke new ground for women in the Danish art establishment. She became the first woman to hold a professorship at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, the very institution that had once denied her entry as a student. She was also elected to the Academy's Plenary Assembly and served on its council, positions of considerable influence. This was a landmark achievement, paving the way for future generations of women artists in Denmark. Her role within the Academy allowed her to advocate for reforms and greater opportunities for women in the arts.

She continued to paint prolifically, primarily focusing on portraits of notable Danish figures, as well as landscapes and genre scenes. Her studio in Copenhagen became a meeting place for artists and intellectuals. She was a contemporary of the Skagen Painters, such as Anna Ancher, Michael Ancher, and P.S. Krøyer, who were revolutionizing Danish art with their plein-air realism, though Wegmann's path was more internationally oriented through Munich and Paris. Nevertheless, she was part of this broader movement towards modernism in Danish art.

The Danish Art Scene and Wegmann's Place Within It

Upon her return to Denmark, Bertha Wegmann entered an art scene that was itself undergoing significant transformation. The Danish Golden Age had given way to new artistic currents, with artists increasingly looking beyond national borders for inspiration. The "Modern Breakthrough" (Det Moderne Gennembrud), a literary and artistic movement championed by Georg Brandes, called for art and literature to engage with contemporary social issues and embrace realism and naturalism.

While Wegmann's training was international, her work resonated with these evolving Danish sensibilities. Her realistic yet psychologically nuanced portraits and her light-filled landscapes found favor. Her success in Paris brought a cosmopolitan prestige to the Danish art world. As a professor at the Royal Academy, she was in a position to influence younger artists, although the extent of her direct pedagogical impact versus her role as a pioneering figure is an area for further art historical research.

She was a contemporary of other notable Danish women artists like Anna Ancher, who was a central figure in the Skagen colony. While their styles and career paths differed—Ancher being more closely associated with the Skagen group's specific brand of realism and Wegmann having a more broadly European academic and Impressionist-influenced background—both women achieved remarkable success and recognition in a male-dominated field, contributing significantly to the richness of Danish art at the turn of the century. Wegmann's role as an institutional pioneer, however, set her apart.

Later Years, Enduring Influence, and Anecdotes

Bertha Wegmann remained an active artist throughout her life. She continued to exhibit her work and was a respected member of the Danish cultural elite. Her dedication to her art was profound. An anecdote surrounding her death in Copenhagen in 1926, at the age of 79 (or 78, sources vary slightly on exact age at death), suggests she was working in her studio just hours before she passed away. This story, whether entirely factual or somewhat embellished, speaks to her lifelong commitment to her artistic practice, a "dramatic tragedy" of an artist devoted to her calling until the very end.

Another interesting aspect of her work, noted by some scholars, is the potential symbolism in her paintings, such as the depiction of dandelions, which has been interpreted as a subtle nod to women's suffrage and the fight for equal rights – the resilient wildflower pushing through adversity. This adds another layer to understanding her as an artist conscious of the social currents of her time.

Despite her considerable success during her lifetime, including numerous awards and her groundbreaking role at the Royal Danish Academy, Bertha Wegmann's name, like those of many women artists of her era, gradually faded from mainstream art historical narratives in the decades following her death. The art world, for much of the 20th century, tended to prioritize a canon largely dominated by male artists.

Rediscovery and Legacy

The late 20th and early 21st centuries have witnessed a significant re-evaluation of art history, with concerted efforts to rediscover and reinstate women artists who were unfairly marginalized. Bertha Wegmann is among those whose contributions are now being increasingly recognized and celebrated. Exhibitions dedicated to her work, and the inclusion of her paintings in broader surveys of 19th-century and women's art, have brought her talent to a new generation.

Her legacy is multifaceted. Artistically, she was a master of portraiture, capable of capturing profound psychological depth, and a skilled painter of landscapes and still lifes who adeptly synthesized academic training with modern influences like Impressionism and Naturalism. Her work stands as a testament to the high caliber of art produced by women during this period.

Institutionally, her achievement as the first female professor at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts was a watershed moment. She broke down significant barriers and served as an inspiring role model. Her advocacy for women in the arts contributed to a slow but steady change in their status and opportunities. Today, Bertha Wegmann is rightfully considered one of Denmark's important painters of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a pioneer whose life and work offer rich insights into the artistic and social dynamics of her time. Her paintings are held in major Danish museums, including the Hirschsprung Collection and the National Gallery of Denmark (SMK), ensuring her art continues to be seen and appreciated.

Conclusion: An Enduring Artistic Voice

Bertha Wegmann's journey from a young girl with a passion for drawing in Copenhagen to an internationally acclaimed artist and a pioneering academic figure is a compelling story of talent, perseverance, and dedication. She navigated the challenges faced by women artists in the 19th century with remarkable success, forging a distinct artistic voice that blended rigorous training with a modern sensibility. Her portraits offer intimate glimpses into the lives of her contemporaries, while her landscapes and still lifes celebrate the beauty of the world around her with a vibrant, light-filled palette.

As art history continues to broaden its scope and embrace a more inclusive narrative, Bertha Wegmann's contributions are being rightfully acknowledged. She was not merely a "woman artist" but a significant artist in her own right, whose work enriched the Danish and broader European art scenes. Her legacy endures in her captivating paintings and in the path she helped clear for women who followed her into the world of professional art.