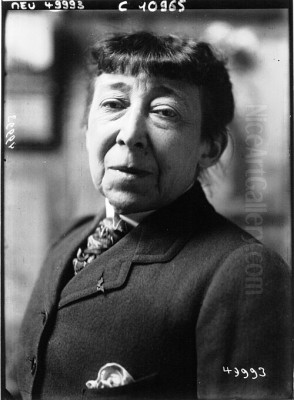

Louise Abbéma stands as a significant figure in the vibrant Parisian art scene of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. A painter, sculptor, and designer, she navigated the complexities of the Belle Époque art world with remarkable success, achieving recognition and accolades in a field still largely dominated by men. Her work, characterized by its elegance, light touch, and often intimate subject matter, captured the spirit of her time, while her life, particularly her close association with the legendary actress Sarah Bernhardt, continues to fascinate historians and art lovers alike. Abbéma's career offers a compelling window into the artistic currents, social dynamics, and evolving role of women artists during a transformative period in French history.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born on October 30, 1853, in Étampes, Essonne, France, Louise Abbéma entered a world of privilege and cultural refinement. Her family was affluent and well-connected within Parisian society, providing her with an environment conducive to artistic pursuits from a young age. Unlike many women of her era who might have pursued art merely as a pastime, Abbéma demonstrated serious ambition and talent early on.

Her formal artistic training began in her teenage years under the tutelage of respected figures in the Parisian art establishment. She studied with Charles Joshua Chaplin, known for his elegant, somewhat Rococo-revival portraits of women. Chaplin's influence might be seen in the grace and decorative quality present in some of Abbéma's work. She also learned from Jean-Jacques Henner, an artist famed for his ethereal nudes and portraits, often characterized by a soft, sfumato-like modeling and a distinctive reddish palette.

Perhaps most significantly, she trained with Carolus-Duran, a highly sought-after portraitist and a charismatic teacher whose atelier attracted numerous students, including the famed American expatriate John Singer Sargent. Carolus-Duran advocated for a direct approach to painting, emphasizing brushwork and capturing the immediate impression, elements that Abbéma would incorporate into her own developing style, blending them with more traditional academic finishes. This diverse training equipped her with a strong technical foundation while exposing her to different stylistic approaches.

The Breakthrough: Portrait of Sarah Bernhardt

Abbéma's career trajectory took a dramatic upward turn in 1875, when she was just 23 years old. She painted a portrait of the internationally renowned actress Sarah Bernhardt, already a superstar of the French stage. This portrait, exhibited at the prestigious Paris Salon, garnered significant attention and critical acclaim, effectively launching Abbéma's public career. The painting captured not only Bernhardt's likeness but also her theatrical charisma and enigmatic presence.

The connection between Abbéma and Bernhardt extended far beyond this single commission. The two women developed a deep and enduring relationship that lasted throughout their lives. They were constant companions, frequently seen together in Parisian society, and collaborated on artistic projects. Abbéma produced numerous portraits of Bernhardt in various media, including paintings, drawings, and even a bronze medallion.

The exact nature of their relationship has been the subject of much speculation. Contemporary accounts and later evidence strongly suggest an intimate, romantic bond. A painting depicting the two women boating, donated to the Comédie-Française in 1990, was accompanied by documentation stating it commemorated an anniversary of their love affair. While neither woman publicly defined their relationship in modern terms, and Abbéma never married, their profound connection was undeniable and central to both their personal lives and Abbéma's artistic identity. Bernhardt became Abbéma's most famous muse and a powerful supporter.

Artistic Style: A Blend of Traditions

Louise Abbéma developed a distinctive artistic style that skillfully blended elements from different traditions. While she operated within the established structures of the art world, regularly exhibiting at the official Salon, her work often displayed a lightness and vibrancy associated with Impressionism. She employed fluid, relatively quick brushstrokes and demonstrated a keen interest in capturing the effects of light, particularly in her floral studies and outdoor scenes.

However, her work rarely dissolved form to the extent seen in the paintings of Claude Monet or Camille Pissarro. Especially in her portraits, she retained a degree of academic finish and attention to detail, ensuring a clear likeness and a sense of elegance that appealed to her clientele. This hybrid approach allowed her to bridge the gap between the avant-garde and the more conservative tastes favored by the Salon juries and the public.

Abbéma's subject matter was varied, but she became particularly known for her portraits, especially of women and children, and her exquisite depictions of flowers. Her floral still lifes are often characterized by their decorative arrangements and vibrant colors. She also tackled allegorical themes, such as her well-known panels representing The Seasons. Furthermore, the influence of Japonisme, the European fascination with Japanese art and aesthetics, is evident in some of her compositions, particularly in their decorative flatness and asymmetrical arrangements, an influence shared with contemporaries like James Abbott McNeill Whistler and Edgar Degas. While influenced by Impressionists like Édouard Manet in terms of capturing modern life and using bolder brushwork, Abbéma forged her own path.

Representative Works and Major Commissions

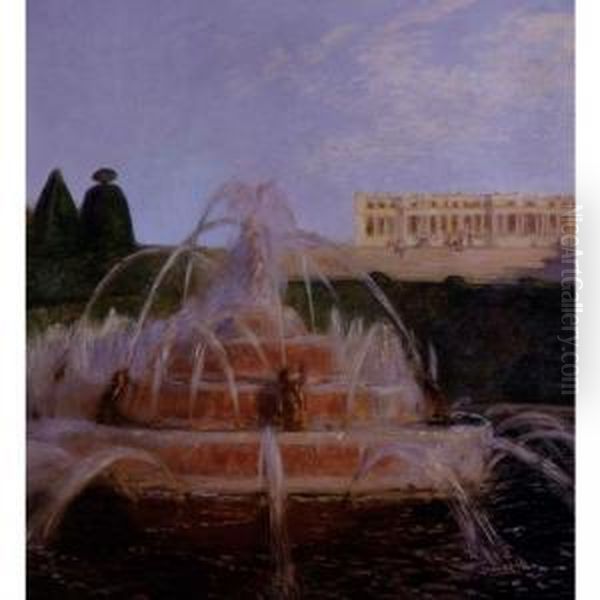

Beyond the famous early portrait of Sarah Bernhardt, Abbéma created a substantial body of work throughout her long career. Among her most recognized paintings are allegorical series like The Seasons, which allowed her to explore decorative compositions and idealized female forms representing different times of the year. Works such as April Morning, Place de la Concorde, In the Flowers, and Winter showcase her skill in handling light, color, and atmosphere, often imbued with a sense of charm and elegance characteristic of the Belle Époque.

Her portraits remained a cornerstone of her practice. She painted numerous society figures, fellow artists, and political leaders, demonstrating her ability to capture both likeness and personality. Her repeated depictions of Sarah Bernhardt remain iconic, charting their long relationship and Bernhardt's evolving public persona. These portraits often incorporated luxurious fabrics and floral elements, enhancing the sense of refinement.

Abbéma was also accomplished in decorative arts and received several important public commissions. She created decorative panels and murals for significant Parisian landmarks, including the Paris Town Hall (Hôtel de Ville) and the Paris Opera House. Her decorative work extended beyond Paris; she designed panels for the Governor's Palace in Dakar, Senegal, then a French colony. These large-scale projects demonstrated her versatility and her acceptance within the official art establishment, which entrusted her with decorating prominent public spaces. She also worked as an illustrator for books and contributed designs for publications.

Navigating the Art World: Success and Recognition

Louise Abbéma achieved a level of professional success rare for women artists of her time. Her regular participation in the Paris Salon, the main venue for artists seeking recognition and patronage, was crucial. From her debut onwards, her works were frequently accepted and often well-received by critics and the public. This consistent presence kept her name in the public eye and led to numerous commissions, both private and public.

Her success was not limited to France. Abbéma's work was included in major international exhibitions, notably the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Her paintings were displayed in the Woman's Building, a space dedicated to showcasing the achievements of women across various fields, highlighting her status as an internationally recognized female artist alongside contemporaries like Mary Cassatt and Berthe Morisot, though her style remained distinct from these core Impressionists.

Abbéma received several prestigious honors throughout her career, further cementing her status. She was awarded the Palmes Académiques and, significantly, was made a Chevalier of the Legion of Honour in 1906, a high distinction rarely bestowed upon women artists at the time. She was even referred to as the "Official Painter of the Third Republic," indicating her acceptance and integration within the state-sponsored art system, a position contrasting sharply with the more rebellious stance of many avant-garde painters like Paul Gauguin or Vincent van Gogh. She also contributed writings on art to periodicals such as the Gazette des Beaux-Arts and L'Art, engaging with the art discourse of her day.

The Artist as "New Woman"

Louise Abbéma embodied many characteristics associated with the "New Woman" emerging in the late nineteenth century: educated, financially independent, professionally successful, and navigating life outside the conventional path of marriage and domesticity. Her successful career as an artist provided her with autonomy and a public profile. Her lifelong, devoted relationship with Sarah Bernhardt, while perhaps unconventional by societal standards, further marked her independence from traditional expectations.

However, Abbéma's relationship with feminism was complex. While her life choices could be seen as inherently feminist, she reportedly expressed conservative views on certain aspects of the women's movement, such as opposing women wearing masculine attire. This nuance reflects the varied ways women negotiated their identities and ambitions during a period of significant social change. Regardless of her stated views, her visibility and success served as an inspiration and paved the way for subsequent generations of women artists. She demonstrated that a woman could achieve prominence and financial independence through artistic talent and determination, challenging the prevailing gender norms of the era, much like the pioneering animal painter Rosa Bonheur had done in an earlier generation.

Contemporaries and Artistic Milieu

Abbéma operated within a rich and diverse artistic milieu in Paris. Her teachers – Chaplin, Henner, Carolus-Duran – connected her to established academic and portraiture traditions. Her association with Sarah Bernhardt placed her at the center of Parisian cultural life, intersecting with the worlds of theatre, literature, and art. Bernhardt herself was a patron of the arts, famously commissioning Art Nouveau posters from Alphonse Mucha and being painted by artists like Georges Clairin.

Abbéma exhibited alongside a wide range of artists at the Salon, from staunch academic painters like William-Adolphe Bouguereau and Jean-Léon Gérôme to Impressionists and other modernists who occasionally participated. While her style differed, she would have been aware of the radical experiments of Monet, Renoir, Degas, and Pissarro. Her own work, with its blend of academic finish and Impressionistic light, reflects a negotiation between these different artistic poles.

Her engagement with Japonisme connects her to a broader trend embraced by artists like Whistler, Manet, Degas, Mary Cassatt, and even Post-Impressionists like Van Gogh and Gauguin, each interpreting Japanese aesthetics in their unique ways. As a successful portraitist, she worked within a genre also populated by international figures like John Singer Sargent (a fellow student of Carolus-Duran) and Giovanni Boldini, known for their dazzling depictions of Belle Époque society. Abbéma carved her own niche within this competitive landscape, focusing often on female subjects and incorporating a distinct decorative sensibility.

Later Life and Legacy

Louise Abbéma continued to work and exhibit well into the twentieth century, adapting her style subtly over time but remaining largely faithful to the elegant aesthetic she had established. She remained a respected figure in the Paris art world until her death in Paris on July 10, 1927. She was buried in the Père Lachaise Cemetery, the final resting place of many notable figures, including Sarah Bernhardt, who had predeceased her in 1923.

For much of the mid-twentieth century, like many women artists and those working outside the main narratives of modernism, Abbéma's work received less critical attention. However, the resurgence of interest in women's art history and Belle Époque culture starting in the late twentieth century led to a re-evaluation of her contributions. Her paintings are now held in numerous museum collections in France and internationally, including the Musée d'Orsay in Paris.

Today, Louise Abbéma is recognized as a talented and successful artist who skillfully navigated the art world of her time. Her work provides valuable insight into the tastes and aesthetics of the Belle Époque. Her portraits, especially those of Sarah Bernhardt, remain compelling documents of a legendary figure and a unique relationship. Her career stands as a testament to the possibilities for women artists in the late nineteenth century, and her blend of academic skill, Impressionist sensibility, and decorative flair continues to earn appreciation. She remains an important figure for understanding the diversity of artistic practice beyond the canonical avant-garde movements.

Conclusion

Louise Abbéma's life and career offer a rich tapestry woven from artistic ambition, social navigation, personal relationships, and historical context. As a painter, sculptor, and designer, she achieved remarkable success, earning official recognition and leaving behind a significant body of work characterized by elegance, technical skill, and a sensitivity to the nuances of Belle Époque society. Her enduring connection with Sarah Bernhardt adds a layer of personal intrigue, while her position as a prominent female artist highlights the changing roles of women during her era. Bridging academic tradition and modern influences like Impressionism and Japonisme, Abbéma created a unique artistic identity that continues to resonate, securing her place as a noteworthy artist of her generation.