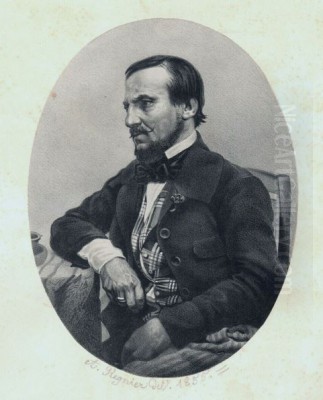

Camille Joseph Étienne Roqueplan stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the vibrant tapestry of 19th-century French art. Born on February 18, 1802, in Mallemort, a picturesque commune in the Bouches-du-Rhône department of southern France, near the Bordeaux region, Roqueplan's life and career unfolded during a period of profound artistic and social transformation. He died in Paris on September 29, 1855, leaving behind a diverse body of work that encapsulates the spirit of Romanticism while also hinting at the emerging trends that would shape the future of art. Known for his adeptness in landscape painting, genre scenes, historical subjects, and even animal portraiture, Roqueplan was a multifaceted artist whose contributions extended beyond his own canvases to influence his contemporaries.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

From a young age, Camille Roqueplan exhibited a precocious talent for drawing and painting. However, sources suggest an initial period of reluctance or internal struggle before he fully committed himself to an artistic career. This hesitation, despite his evident gifts, adds an intriguing layer to his early biography. By the age of eighteen, his passion for art had solidified, leading him to seek formal training. This decision set him on a path that would see him engage with some of the leading artistic figures and institutions of his time.

His family background, while not extensively detailed in all records, appears to have been supportive enough to allow him to pursue his artistic inclinations. The environment of southern France, with its distinctive light and landscapes, may have also played an early, subconscious role in shaping his visual sensibilities, which would later manifest in his mature works, particularly his landscapes.

Formative Training and Influences

Roqueplan's formal artistic education began under the tutelage of several distinguished masters. He initially studied with Antoine-Jean Gros, a prominent painter who, despite being a student of the arch-Neoclassicist Jacques-Louis David, became a key figure in the transition towards French Romanticism. Gros was renowned for his large-scale historical paintings, often depicting Napoleonic battles with a dramatic flair and emotional intensity that broke from the stoic restraint of Neoclassicism. This exposure to Gros's dynamic compositions and rich color palette undoubtedly left a mark on the young Roqueplan.

He also trained with Philibert-Louis Debucourt, often cited as Alexandre Debucourt, a painter and engraver celebrated for his elegant and witty genre scenes depicting Parisian society. Debucourt's mastery of color aquatint and his keen observation of contemporary manners likely instilled in Roqueplan an appreciation for capturing the nuances of everyday life and the subtleties of social interaction, which would become evident in his own genre paintings.

In 1818, Roqueplan furthered his studies by enrolling at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, the epicenter of academic art training in France. This institution provided a rigorous grounding in classical principles, drawing from antique sculpture, and the study of anatomy. While Romanticism was often positioned as a rebellion against academic strictures, the foundational skills acquired at the École were invaluable even to artists who would later diverge from its more conservative tenets.

Beyond these formal instructors, Roqueplan was also associated with Achille Etna Michallon, a pioneering landscape painter who won the first Prix de Rome for historical landscape in 1817. Though Michallon died young, his emphasis on direct observation of nature was influential. Roqueplan also reportedly received guidance from Abel de Pujol, another history painter and student of David, who was known for his religious and mythological scenes. This diverse range of teachers exposed Roqueplan to various artistic approaches, from the grand manner of history painting to the intimacy of genre and the burgeoning field of landscape.

Embracing the Spirit of Romanticism

Camille Roqueplan emerged as an artist during the ascendancy of Romanticism in France. This artistic, literary, and intellectual movement, which flourished from the late 18th century through the mid-19th century, emphasized emotion, individualism, the glorification of the past and nature, and a departure from the rationalism of the Enlightenment and the strictures of Neoclassicism. Artists like Théodore Géricault, with his harrowing Raft of the Medusa, and Eugène Delacroix, with his vibrant and passionate historical and orientalist scenes, were leading figures of this movement.

Roqueplan's work embodies many characteristics of Romanticism. His historical and literary scenes often feature dramatic narratives, intense emotion, and a rich, evocative use of color. He was drawn to subjects that allowed for expressive storytelling, whether drawn from history, literature (particularly the works of Sir Walter Scott, which were immensely popular at the time), or contemporary events. His landscapes, too, often possess a Romantic sensibility, capturing the atmospheric qualities of nature and sometimes imbuing them with a sense of melancholy or grandeur.

His style was not monolithic, however. It was an amalgamation, blending the dramatic fervor of Romanticism with an appreciation for the technical finesse and coloristic richness found in 17th-century Venetian and Dutch painting. This eclecticism allowed him to tackle a wide range of subjects with a distinctive visual language. He was particularly admired for his skillful handling of light and shadow, his vibrant palette, and his ability to create dynamic, engaging compositions.

The Paris Salon and Public Recognition

The Paris Salon, the official art exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts, was the primary venue for artists to display their work and gain recognition during the 19th century. Roqueplan made his debut at the Salon in 1822 and continued to exhibit regularly until his death in 1855. His participation in these prestigious exhibitions was crucial for establishing his reputation and securing patronage.

His works at the Salon covered the gamut of his artistic interests. In 1824, he received a second-class medal, an early acknowledgment of his talent. He achieved a first-class medal in 1828. His paintings often attracted favorable attention for their technical skill and appealing subject matter. While he may not have achieved the same level of fame as the foremost titans of Romanticism like Delacroix, Roqueplan carved out a respected niche for himself. He was particularly successful with his genre scenes, which depicted elegant figures in charming, often sentimental, situations, appealing to the tastes of the burgeoning middle-class art market.

His historical paintings also garnered acclaim. These works often focused on poignant or dramatic moments, rendered with a sensitivity to historical detail and a flair for narrative. His landscapes, particularly those inspired by his travels, such as his views of the Pyrenees, were admired for their atmospheric beauty and picturesque qualities.

A Diverse Oeuvre: Exploring Different Genres

Camille Roqueplan's versatility is one of his defining characteristics as an artist. He moved with facility between different genres, bringing his unique sensibility to each.

Historical and Literary Scenes:

Roqueplan produced a number of paintings based on historical events and literary sources. One notable example is The Death of the Spy Morris, a subject that allowed for dramatic tension and emotional expression. He also painted scenes inspired by the life of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, such as Young Jean-Jacques Rousseau, reflecting the Romantic era's fascination with the philosopher's life and ideas. His interpretations of scenes from the novels of Sir Walter Scott were also popular, tapping into the widespread enthusiasm for Scott's historical romances. These works often showcased his ability to create compelling narratives and to costume his figures in historically evocative attire.

Genre Paintings:

Perhaps his most commercially successful works were his genre scenes. These paintings typically depicted elegant figures in domestic interiors or picturesque outdoor settings, engaged in activities such as reading, conversation, or courtship. Works like The Fan or The Love Letter exemplify this aspect of his oeuvre. These scenes are characterized by their refined execution, delicate color harmonies, and charming sentiment. They often evoke a sense of nostalgia or idealized romance, appealing to the sensibilities of the July Monarchy period. His genre paintings show an affinity with the "troubadour style," a romanticized depiction of the Middle Ages and Renaissance, as well as an influence from 18th-century French painters like Jean-Antoine Watteau and Jean-Honoré Fragonard, and 17th-century Dutch masters.

Landscapes:

Roqueplan was also an accomplished landscape painter. He traveled to the Pyrenees, and the sketches and paintings resulting from these excursions capture the rugged beauty and atmospheric conditions of the mountainous region. The Well in the Pyrenees is a fine example of his landscape work, showcasing his ability to render natural scenery with both accuracy and poetic feeling. His landscapes often feature a rich interplay of light and shadow and a sensitivity to the changing moods of nature. While not strictly a member of the Barbizon School – a group of painters including Théodore Rousseau, Jean-François Millet, and Charles-François Daubigny, who emphasized realistic depictions of rural life and landscape – Roqueplan shared their interest in direct observation of nature and was certainly connected to its key figures.

Animal Paintings:

Roqueplan also ventured into animal painting, a genre that gained popularity during the Romantic era. His depictions of animals, such as lions, were often imbued with a sense of power and wildness, reflecting the Romantic fascination with the untamed aspects of nature. The Lion in Love, based on La Fontaine's fable, is one of his well-known works in this genre, combining narrative, animal portraiture, and a touch of allegory.

Portraiture:

While perhaps less central to his output, Roqueplan did undertake portrait commissions. His portraits, like his other works, would have been characterized by their refined technique and ability to capture the sitter's likeness and personality.

The Art of Etching:

Beyond painting, Roqueplan was a skilled printmaker, particularly in the medium of etching. He created numerous etchings, often reproducing his own paintings or creating original compositions. His print La Lecture (The Reading) is a notable example, demonstrating his delicate touch and mastery of line in this medium. His involvement in printmaking helped to disseminate his images to a wider audience and contributed to the revival of etching as an original art form in the 19th century. He also contributed illustrations to books, including works by Victor Hugo, sometimes in collaboration with other artists like Daubigny.

Roqueplan's Circle: Connections and Influence

Camille Roqueplan was well-connected within the Parisian art world. His studio was a meeting place, and he played a role in fostering connections between artists. He was instrumental in introducing the landscape and animal painter Constant Troyon to Théodore Rousseau and Jules Dupré (Louis-Victor Dupré). This introduction was significant, as Rousseau and Dupré were central figures in the Barbizon School, and their influence was crucial to Troyon's development. Troyon, who initially painted in a more conventional style, shifted towards a more naturalistic approach to landscape and became one of the most celebrated animal painters of his generation, thanks in part to these connections facilitated by Roqueplan.

Roqueplan was also acquainted with Louis Cabat, another landscape painter associated with the Barbizon group, and Narcisse Diaz de la Peña, known for his richly colored forest scenes and mythological figures. An anecdote recounts Roqueplan encountering Théodore Rousseau, Jules Dupré, and Diaz de la Peña in the park of Saint-Cloud in 1832, a meeting that underscores his proximity to this circle of innovative landscape painters. His relationship with Charles-François Daubigny, another key Barbizon figure and a pioneer of plein-air painting, is evidenced by their collaborative illustration work.

His artistic influences were diverse. He admired the color and light of Venetian masters and the intimate realism of 17th-century Dutch painters. He also drew inspiration from the elegant compositions and delicate sensibility of Pierre-Paul Prud'hon, a French Romantic painter whose work bridged Neoclassicism and Romanticism with a distinctive, soft, and sensual style. This ability to synthesize various influences while maintaining his own artistic voice was a hallmark of Roqueplan's approach.

Anecdotes, Controversies, and Lesser-Known Aspects

Several interesting details and minor controversies surround Camille Roqueplan's life and work. As mentioned, he reportedly resisted a career in painting initially, despite his early talent. This internal conflict, if true, adds a human dimension to the artist's biography.

His artistic views could also be nuanced. While a Romanticist, he was said to have expressed opposition to what he termed the "true windmill" style of some Old Dutch masters, perhaps indicating a desire for a more idealized or poetically interpreted realism rather than a purely prosaic depiction of reality. This suggests a sophisticated engagement with art history and a discerning eye.

Attribution issues have occasionally arisen concerning his work. For instance, a painting titled Paris Street Scene has been associated with Roqueplan, but its definitive attribution has been debated by scholars. Such uncertainties are not uncommon for artists of this period, especially those whose oeuvres have not been exhaustively cataloged. Indeed, it has been noted that Roqueplan's body of work, particularly his drawings, remains relatively under-researched compared to some of his more famous contemporaries.

A darker chapter relates to the fate of some of his artworks during World War II. Like many European artists, particularly those whose works were in Jewish collections or deemed "degenerate" by the Nazi regime (though Roqueplan's style wouldn't typically fall into the latter category), some of his paintings were looted. Efforts to restitute Nazi-looted art continue to this day, and works by Roqueplan have been identified in these contexts. Some of his paintings are now held in prestigious public collections, including the Louvre in Paris, which acquired works that had been recovered after the war.

He was also involved in decorative projects, such as murals for the west wing of the Luxembourg Palace. However, these works reportedly did not achieve widespread acclaim, perhaps overshadowed by other, more monumental decorative schemes of the period or by his more popular easel paintings.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

Camille Roqueplan continued to paint and exhibit throughout his career, adapting to the evolving tastes of the art world while remaining true to his core artistic vision. He maintained a steady output of historical scenes, genre paintings, and landscapes, solidifying his reputation as a skilled and versatile artist. His death in Paris on September 29, 1855, at the relatively young age of 53, cut short a productive career.

Despite not being as universally recognized today as giants like Delacroix or Corot, Camille Roqueplan's contributions to 19th-century French art are undeniable. He was a quintessential Romantic artist in many respects, yet his work also displays a refinement and charm that appealed to a broad audience. His ability to navigate different genres with success speaks to his technical mastery and artistic intelligence.

His influence on other artists, notably Constant Troyon, demonstrates his role as a supportive figure within the artistic community. His paintings continue to be appreciated for their aesthetic qualities, their historical interest, and their embodiment of the Romantic spirit.

Works by Camille Roqueplan can be found in numerous public collections in France and internationally. Besides the Louvre, his paintings are held by the Palais des Beaux-Arts de Lille, the Musée de Grenoble, the Musée Condé in Chantilly, and the Wallace Collection in London. In the United States, the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Massachusetts, also holds examples of his work. The presence of his art in these esteemed institutions attests to his enduring significance.

Conclusion: A Refined Romantic Voice

Camille Joseph Étienne Roqueplan was an artist of considerable talent and versatility whose career spanned a dynamic period in French art history. From his early training under masters like Gros and Debucourt to his active participation in the Paris Salons and his engagement with the leading figures of Romanticism and the Barbizon School, Roqueplan forged a distinctive artistic identity.

His oeuvre, encompassing dramatic historical narratives, elegant genre scenes, evocative landscapes, and spirited animal paintings, reflects the multifaceted interests of the Romantic era. He skillfully blended technical polish with emotional expression, creating works that were both visually appealing and intellectually engaging. While he may be considered one of the "petits maîtres" (minor masters) of Romanticism by some, his contribution was significant, enriching the artistic landscape of his time and leaving behind a body of work that continues to charm and impress. His role as a mentor and a connector within the art world further underscores his importance. Camille Roqueplan remains a noteworthy figure, a refined Romantic voice whose art provides valuable insights into the cultural and aesthetic currents of 19th-century France.