Introduction: An Artist Between Eras

Hippolyte Delaroche, known to the world as Paul Delaroche, stands as one of the most celebrated and influential French painters of the 19th century. Born in Paris on July 17, 1797, and passing away in the same city on November 4, 1856, Delaroche carved a unique niche for himself within the vibrant and often contentious art world of his time. Primarily recognized as a history painter, his career unfolded during a period of transition, bridging the stern Neoclassicism inherited from masters like Jacques-Louis David and the burgeoning emotionalism of Romanticism championed by figures such as Eugène Delacroix. Delaroche achieved immense popularity during his lifetime, mastering a style characterized by meticulous realism, dramatic intensity, and a keen sense for narrative, often drawing upon pivotal moments in French and English history. His work resonated deeply with the public and critics alike for decades, though his reputation would later undergo significant re-evaluation with the rise of modern art movements.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Paul Delaroche was born into an environment steeped in art. His family was affluent and well-connected within the Parisian art establishment. His father, Grégoire-Hippolyte de la Roche, was a respected art expert and dealer, while his uncle, J.-V. de la Roche, served as the curator of prints at the Bibliothèque Nationale. Furthermore, his elder brother, Jules-Hippolyte Delaroche, also pursued a career as a painter, specializing in historical subjects. This familial immersion undoubtedly provided young Paul with invaluable early exposure and encouragement. Initially, Delaroche harbored ambitions of becoming a landscape painter, studying for a time under Louis Étienne Watelet. However, finding limited success in this genre, he shifted his focus towards the more prestigious and demanding field of history painting.

His formal training continued, and although not a direct pupil of Antoine-Jean Gros, he was significantly influenced by Gros's dramatic historical canvases, which themselves represented a transition from the severity of David towards a more colourful and emotionally charged style. Delaroche absorbed the lessons of Neoclassical precision and finish, particularly admiring the linear clarity found in the works of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, while simultaneously embracing the theatrical potential and emotional depth explored by the Romantics. His public debut came at the Paris Salon of 1822 with the painting Joash rescued by Jehosheba. This work immediately garnered attention, signaling the arrival of a significant new talent capable of handling large-scale historical narratives with technical skill and dramatic flair.

Rise to Prominence: The Juste Milieu

The 1822 Salon marked a turning point not only for Delaroche but also for the direction of French history painting. It was here that he reportedly met and befriended Théodore Géricault and Eugène Delacroix, two titans of French Romanticism. Together, these artists, despite their stylistic differences, came to represent the dynamic core of the historical painting school in Paris during the 1820s and 1830s. Delaroche quickly distinguished himself, navigating a path often described as the juste milieu – a "happy medium" that sought to reconcile the opposing tendencies of Neoclassicism and Romanticism. He adopted the meticulous finish, careful drawing, and compositional clarity associated with Ingres and the academic tradition, but infused his subjects with a heightened sense of drama, pathos, and historical specificity that appealed to Romantic sensibilities.

His choice of subjects, often drawn from English and French history, particularly moments of tragedy, conflict, or poignant human drama involving royalty and famous figures, proved immensely popular with the Salon audiences. Works like The Death of Queen Elizabeth (exhibited Salon of 1828) showcased his ability to blend historical research (or perceived authenticity) with compelling emotional narratives. The painting depicted the aged queen dying amidst the splendors of her court, capturing a sense of fading power and human vulnerability. Similarly, The Children of Edward IV in the Tower (c. 1830), portraying the doomed young princes awaiting their fate, struck a chord with its blend of historical pathos and detailed, almost tangible realism. Delaroche's success was recognized with a gold medal at the Salon of 1824, solidifying his position as a leading artist of his generation.

The Height of Fame: Masterworks and Recognition

The 1830s marked the zenith of Delaroche's fame and influence. His works were eagerly anticipated at the Salon, and he became one of the most commercially successful artists in Europe. His masterpiece, and arguably his most enduringly famous painting, is The Execution of Lady Jane Grey, exhibited at the Salon of 1834 to sensational acclaim. This large canvas depicts the moments before the execution of the young "Nine Days' Queen" of England. Delaroche masterfully orchestrates the scene for maximum emotional impact: the blindfolded Jane, dressed in luminous white satin, tentatively reaches for the execution block, guided by the Lieutenant of the Tower, while her distraught ladies-in-waiting collapse in grief. The painting's power lies in its combination of meticulous detail (the textures of fabric, the straw on the floor, the executioner's axe) and its intense focus on human suffering and vulnerability. It became an iconic image, widely reproduced and admired for its historical drama and technical brilliance.

Other significant works from this period further cemented his reputation. Cromwell Gazing at the Body of Charles I (1831) offered a somber meditation on power and mortality, depicting the victorious Cromwell contemplating his executed rival. Later, Delaroche would tackle Napoleonic themes, most notably in his Bonaparte Crossing the Alps (1848-1850). This work presented a starkly realistic counterpoint to Jacques-Louis David's idealized equestrian portrait of Napoleon, showing a weary Bonaparte on a mule, guided through a treacherous, snow-bound pass – an image emphasizing the human struggle behind the heroic myth. His achievements earned him prestigious official recognition: in 1832, he was elected a member of the Institut de France (Académie des Beaux-Arts), and in 1833, he was appointed a professor at the influential École des Beaux-Arts, succeeding his mentor figure, Baron Gros.

Teaching and Influence

Delaroche's role as a professor at the École des Beaux-Arts was highly significant, allowing him to shape the next generation of artists. He was known as a dedicated and influential teacher, and his studio attracted numerous students from France and abroad. His teaching methods emphasized rigorous drawing, careful composition, and the importance of historical accuracy (as understood at the time), combined with an encouragement towards achieving dramatic effect and emotional resonance. Among his most notable pupils were Jean-Léon Gérôme, who would become a major figure in French academic art, known for his own highly detailed historical and Orientalist scenes, clearly inheriting Delaroche's meticulous approach.

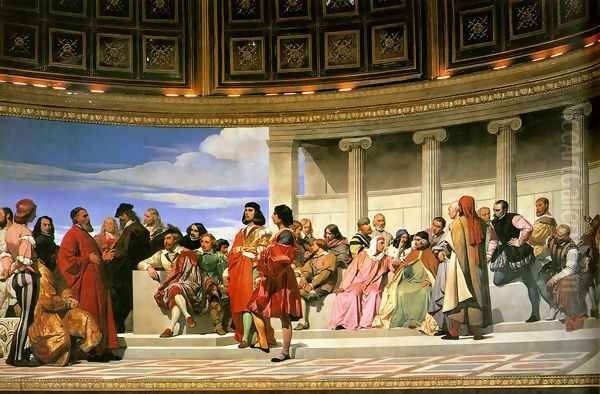

Other prominent students included Thomas Couture, who later painted the celebrated Romans of the Decadence and also became an influential teacher himself; the British history painters Edward Armitage and Charles Lucy; the landscape painter Henry Mark Anthony; and the American artist Francis Davis Millet. Delaroche's pedagogical influence extended beyond individual instruction. Between 1837 and 1841, he undertook the massive commission to paint the Hémicycle, a vast mural decorating the amphitheater of the École des Beaux-Arts. This ambitious work depicted a grand assembly of the greatest artists from antiquity to the 17th century. Delaroche designed the overall composition and painted many of the central figures, reportedly supervising a team that included several of his senior students, making the project itself a form of advanced instruction and collaboration. Through his direct teaching and the subsequent careers of his pupils, Delaroche's artistic principles were widely disseminated.

International Reach: Delaroche in Russia and Beyond

While Delaroche enjoyed immense fame in France, his influence extended significantly beyond its borders, particularly eastward to Russia. Throughout the mid-19th century, his works were highly esteemed within Russian artistic circles. His paintings became known not only through originals acquired by collectors but also, crucially, through the widespread circulation of high-quality engravings and lithographs. These reproductions made his dramatic historical narratives accessible to a broad audience and provided influential models for Russian artists grappling with the development of their own national school of history painting. Artists such as Vasili Timm and Fyodor Bronnikov are known to have been influenced by his style.

Delaroche's Cromwell Gazing at the Body of Charles I was particularly resonant, inspiring Russian artists like Vyacheslav Schwarz and later Nikolay Ge, who adapted Delaroche's blend of historical detail and psychological drama to Russian subjects. The pathos and theatricality of works like The Execution of Lady Jane Grey also found favour. There was even official interest at the highest level: Tsar Nicholas I reportedly admired Delaroche's work greatly and, through the intermediary of the French painter Horace Vernet (Delaroche's father-in-law), attempted to persuade Delaroche to come to Saint Petersburg to undertake commissions, though the invitation was ultimately declined. The proliferation of prints after Delaroche's paintings ensured his status as one of the most internationally recognized European artists of his time, influencing taste and artistic practice far beyond the Paris Salons.

Later Career and Critical Challenges

Despite his continued productivity and public renown, the later stages of Delaroche's career were not without challenges, particularly regarding critical reception. The very qualities that had brought him fame – meticulous detail, theatrical staging, and focus on anecdotal historical moments – began to draw criticism from some quarters, especially as new artistic movements began to emerge. In 1837, his painting St. Cecilia received negative reviews at the Salon, with some critics finding its detailed realism overly laboured or "solemn." This critical coolness, combined perhaps with personal factors, led Delaroche to largely withdraw from exhibiting at the annual Salons, although he continued to work on major commissions like the Hémicycle.

Furthermore, a tragic incident occurred in his studio in 1843 when a student died during a violent hazing ritual. Deeply affected, Delaroche closed his teaching studio, although he retained his professorship. As the century progressed, the rise of Realism under Gustave Courbet, and later Impressionism, shifted artistic priorities away from the historical narratives and polished finish that defined Delaroche's work. Critics increasingly began to view his paintings as overly sentimental, melodramatic, or lacking in profound insight, favouring instead art that engaged more directly with contemporary life or explored new modes of visual representation. Despite these shifting tides of taste and criticism, Delaroche continued to paint, producing significant works like the Bonaparte Crossing the Alps series and various religious scenes until his death in Paris in 1856.

Artistic Style Revisited: Technique and Themes

Paul Delaroche's artistic signature lies in his skillful synthesis of seemingly opposing artistic currents. His technique was grounded in the academic tradition: drawing was paramount, compositions were carefully structured, and surfaces were rendered with a smooth, highly polished finish that minimized visible brushwork, echoing the clarity of Ingres. However, he employed this meticulous technique in the service of subjects and moods more aligned with Romanticism. He excelled at choosing historical moments – often tragic or pivotal episodes from English and French monarchical history – that allowed for the depiction of intense emotion and high drama. His figures, while accurately costumed and placed in historically detailed settings, were primarily vehicles for conveying pathos, suffering, resolve, or vulnerability.

His approach was often described as theatrical. He staged his scenes like a director, carefully arranging figures, lighting, and props to maximize narrative clarity and emotional impact. This sometimes led to accusations of melodrama, but it was precisely this quality that made his works so accessible and compelling to a wide audience. He aimed for a kind of historical verisimilitude, researching costumes and settings, which lent his paintings an air of authenticity, even if the emotional interpretations were highly subjective. Key recurring themes include the fall of the mighty (Death of Elizabeth, Lady Jane Grey, Charles I), moments of intense personal crisis (Children of Edward), and the human side of historical figures (Bonaparte Crossing the Alps). His colour palette was generally rich but controlled, often using dramatic lighting (chiaroscuro) to focus attention and enhance the mood.

Legacy and Re-evaluation

The legacy of Paul Delaroche is complex and has fluctuated over time. For much of the mid-19th century, he was regarded as one of the greatest painters in Europe, the perfect embodiment of the juste milieu, satisfying both academic standards and popular taste for drama and realism. His influence on history painting, both in France and internationally (especially Russia), was undeniable, and his role as a teacher shaped a generation of successful artists, most notably Gérôme. The widespread dissemination of his work through prints ensured his images became deeply embedded in the popular visual culture of the era.

However, with the ascendancy of Modernism, Delaroche's reputation suffered a significant decline. His work came to be seen by many critics as the epitome of conservative, overly polished, and emotionally shallow academic art – precisely the kind of art the Impressionists and subsequent avant-gardes rebelled against. For much of the 20th century, he was relatively neglected by art history, often dismissed as merely a competent but uninspired academician. Yet, in more recent decades, there has been a renewed interest in 19th-century academic art, leading to a more nuanced re-evaluation of Delaroche's contribution. Scholars now acknowledge his technical mastery, his skill as a narrative painter, and his crucial role as a transitional figure who successfully navigated the complex artistic landscape between Neoclassicism and Romanticism. His paintings, particularly The Execution of Lady Jane Grey, continue to hold a powerful fascination for the public, demonstrating the enduring appeal of his dramatic historical vision.

Conclusion: An Enduring Historical Vision

Paul Delaroche remains a significant figure in the history of 19th-century European art. As a master of French history painting, he achieved extraordinary fame by creating works that skillfully blended meticulous academic technique with the dramatic intensity and emotional appeal of Romanticism. His depictions of poignant moments from English and French history, rendered with detailed realism and theatrical flair, captivated audiences and established him as a leading artist of the juste milieu. Through his influential teaching career at the École des Beaux-Arts and the wide circulation of prints after his paintings, his impact extended across Europe, notably influencing the development of history painting in Russia. While his critical fortunes waned with the rise of Modernism, recent scholarship has fostered a greater appreciation for his technical brilliance, his narrative power, and his important position within the artistic dialogues of his time. Delaroche's work stands as a testament to the enduring power of historical drama rendered with consummate skill.