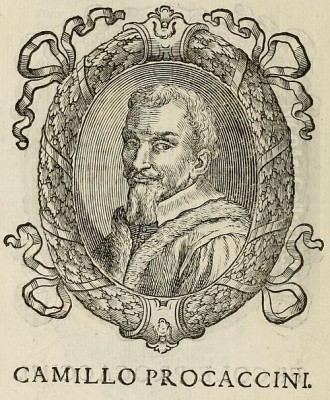

Camillo Procaccini stands as a significant figure in the landscape of Italian art during the transition from the late Renaissance to the early Baroque period. Born in Bologna around 1555, he became one of the most prolific and sought-after painters in Milan during the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. His career, spanning nearly five decades until his death in 1629, was marked by a distinctive Mannerist style, influential commissions, and the leadership of a prominent artistic family. Understanding Camillo Procaccini offers insight into the artistic currents of Lombardy, particularly under the influence of the Counter-Reformation.

Bolognese Beginnings and Early Training

Camillo Procaccini's artistic journey began in Bologna, a city renowned for its vibrant artistic environment. He was the eldest son of Ercole Procaccini the Elder (c. 1520–1595), himself a respected painter and the founder of a notable artistic dynasty. Camillo received his initial training directly from his father, absorbing the fundamentals of painting within the family workshop. This familial connection to the arts provided a solid foundation for his future career.

By 1571, the young Camillo was formally recognized as a student within the painters' guild of Bologna. Significantly, his father, Ercole, held the position of guild leader at that time, underscoring the family's established position within the local art community. This early immersion in the Bolognese art scene exposed Camillo to the prevailing styles and techniques, likely including the works of earlier Emilian masters whose influence would subtly permeate his later output.

The Crucial Roman Experience

Around 1580, seeking to broaden his artistic horizons, Camillo Procaccini traveled to Rome. This period was transformative, exposing him to the monumental works of High Renaissance masters like Michelangelo and Raphael. Their powerful figural compositions and mastery of form left an indelible mark on the young painter. Equally important was his encounter with the contemporary Roman art scene, particularly the works associated with late Mannerism.

Sources indicate that Camillo was particularly influenced by the style of Taddeo Zuccaro (1529–1566), a leading exponent of Roman Mannerism known for his complex frescoes and dynamic compositions. Studying the Central Italian approach to large-scale fresco decoration proved invaluable. This Roman sojourn equipped Camillo with a more sophisticated understanding of complex narrative, dramatic figure arrangement, and the expressive potential of the human form, elements that would become hallmarks of his mature style.

Return to Emilia and the Call to Milan

After his formative years in Rome, Camillo returned briefly to Bologna around 1587. During this period, he likely sought to establish his reputation in his home region. Evidence suggests collaborations, including work alongside the prominent Bolognese painter Ludovico Carracci (1555–1619) on an altarpiece for the Piacenza Cathedral. This interaction with the Carracci, who were pioneering a reformist style moving away from Mannerism, highlights the dynamic artistic exchanges occurring in Emilia at the time.

However, Camillo's destiny lay further north. In the late 1580s, he made the pivotal decision to relocate to Milan. This move marked the beginning of the most significant phase of his career. Milan, under the spiritual leadership of figures like Cardinal Carlo Borromeo (though Borromeo died in 1584, his influence persisted) and later Federico Borromeo, was a major center of the Counter-Reformation, demanding art that was theologically sound, emotionally engaging, and visually impressive. Procaccini's style, honed in Bologna and Rome, was well-suited to meet these demands.

Ascendancy in Milan: Frescoes and Patronage

Camillo Procaccini quickly established himself as a leading artistic force in Milan. His ability to execute large-scale fresco cycles and compelling altarpieces attracted significant patronage from both ecclesiastical authorities and noble families. He received commissions to decorate important churches and private villas, solidifying his reputation throughout Lombardy.

A notable early Milanese project involved frescoes for the Basilica di San Sepolcro. His work increasingly caught the attention of the city's most important patrons. A significant milestone occurred in 1592 when Camillo became the first non-Lombard artist invited to contribute to the decoration of the Milan Cathedral (Duomo). This prestigious commission involved painting the shutters for the cathedral's organ, a task he shared with local artists Giuseppe Meda (c. 1534–1599) and Ambrogio Figino (1553–1608), and later included work on the vaults and dome. This invitation signaled his acceptance into the highest echelons of the Milanese art world.

His success was further bolstered by connections with influential figures. He worked under the patronage of Archbishop Carlo Borromeo's legacy, undertaking commissions such as frescoes for the church of San Chiara in Reggio Emilia. He also received commissions from Don Pedro de Toledo, the Spanish governor of Milan, indicating his appeal extended to the ruling administration. These high-profile projects cemented his status as a premier painter in the region.

Artistic Style: Mannerism Refined for the Counter-Reformation

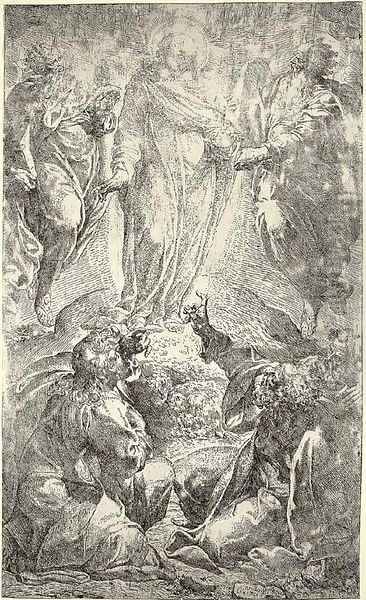

Camillo Procaccini is primarily identified with the Mannerist style, specifically its later iteration as practiced in Northern Italy. His work embodies many key characteristics of Mannerism: complex and often crowded compositions, elongated and elegantly contorted figures (figura serpentinata), sophisticated artificiality, and a vibrant, sometimes acidic color palette. He demonstrated a clear interest in anatomical rendering, often depicting muscular figures in dynamic, strained poses.

However, Procaccini adapted Mannerist conventions to serve the specific spiritual aims of the Counter-Reformation. While maintaining stylistic complexity, his works often possess a heightened emotional intensity and dramatic fervor designed to inspire piety and awe in the viewer. He excelled in depicting scenes of martyrdom and religious ecstasy, emphasizing the suffering and sacrifice inherent in the Catholic faith. This focus on pathos and direct emotional appeal aligns perfectly with the Counter-Reformation's call for art that could instruct and move the faithful.

While influenced by his Roman studies and earlier masters like Correggio (c. 1489–1534) and Parmigianino (1503–1540), particularly in the grace and fluidity of some figures, Camillo developed a distinct personal style. His figures often possess a robust, almost sculptural quality, and his compositions, though intricate, usually maintain narrative clarity. He frequently combined these dramatically rendered figures with backgrounds that incorporated elements of naturalism, creating a unique blend of artificiality and observation. His style offered a powerful alternative to the more classicizing reforms being promoted by the Carracci family (including Annibale Carracci and Agostino Carracci) in Bologna.

Major Works and Notable Commissions

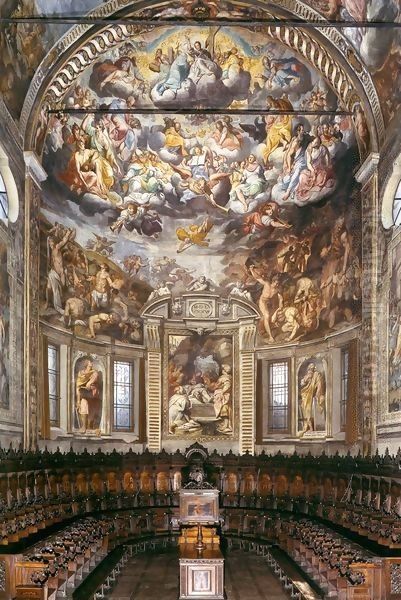

Camillo Procaccini's oeuvre is extensive, dominated by religious subjects executed in both fresco and oil. His contributions to the Milan Cathedral were significant, including the aforementioned organ shutters and later altarpieces like The Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine. These works showcase his ability to handle large-scale compositions with dramatic flair and rich coloring.

His fresco cycles are among his most important achievements. Beyond the Duomo, he executed significant decorations in other Milanese churches, such as San Celso. His work in the Basilica di San Sepolcro further demonstrated his mastery of mural painting. These large-scale projects allowed him to fully deploy his Mannerist vocabulary, filling walls and ceilings with dynamic figures and complex narratives.

Several individual paintings stand out as representative of his style. The Martyrdom of Saint Agnes, known through various versions, exemplifies his focus on dramatic martyrdom scenes, characterized by intense emotion and dynamic composition. Similarly, The Beheading of Saint Victor, created for the church of San Vittore al Corpo in Milan, powerfully conveys the violence and piety of the subject, with its emphasis on muscular anatomy and expressive gestures.

Other notable works include The Last Judgment, a theme allowing for grand compositional complexity and emotional range, and The Baptism of Christ, showcasing his use of strong color contrasts and profound emotional expression. The Visitation, now housed in the Blanton Museum of Art, Austin, Texas, demonstrates his ability to infuse traditional religious scenes with Mannerist elegance and dynamism. His Transfiguration (National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.) and The Coronation of Esther (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) further attest to his skill and the demand for his work. The multiple versions of the Martyrdom of St. Agatha found in the Pinacoteca di Brera, Pinacoteca del Castello Sforzesco, and Museo Civico di Cremona highlight the popularity of certain themes and his workshop's productivity.

His collaboration with Ludovico Carracci on the Piacenza Cathedral altarpiece early in his Milanese period is also noteworthy, indicating his engagement with other leading artists of his time.

The Procaccini Dynasty: A Family Enterprise

Camillo was not the only talented artist in his family. His younger brothers, Giulio Cesare Procaccini (1574–1625) and Carlo Antonio Procaccini (1571–1630), also became accomplished painters. Together, the Procaccini brothers formed one of the most successful and influential artistic workshops in Milan during the early seventeenth century.

While Giulio Cesare developed a distinct style, often characterized by its emotional intensity and sfumato effects reminiscent of Lombard masters, and Carlo Antonio specialized more in landscapes and still lifes, Camillo remained the de facto head of the family enterprise. Sources suggest Camillo played a significant role in managing the workshop's business affairs and coordinating large commissions. This division of labor and familial collaboration allowed the Procaccini workshop to undertake numerous projects simultaneously and cater to a wide range of patrons.

Camillo also played a role in the training of the next generation. While his brothers were primarily trained by their father, Ercole the Elder, Camillo likely served as a mentor, particularly to Carlo Antonio after their father's death. He is also documented as the teacher of the painter Carlo Biffi (fl. early 17th century). The Procaccini workshop became a major force, disseminating their collective style throughout Lombardy and even influencing artists beyond the region.

Later Years, Influence, and Legacy

Camillo Procaccini remained active and highly regarded throughout his long career, continuing to produce works until his death in Milan in 1629. His prolific output ensured that his style became deeply ingrained in the artistic fabric of Lombardy. He was a key figure in sustaining the Mannerist tradition in Milan well into the seventeenth century, even as the Baroque style, championed by artists like Caravaggio (though Caravaggio's direct Milanese impact is debated) and later Lombard masters, began to emerge.

His influence extended beyond Milan. His works were known and collected elsewhere in Italy and even in Spain, partly due to the Spanish rule over Milan and patrons like Don Pedro de Toledo. He successfully navigated the complex artistic and religious landscape of his time, creating works that satisfied the demands of Counter-Reformation patrons while showcasing his considerable technical skill and distinctive Mannerist aesthetic.

Critical Reception and Art Historical Standing

Art historians recognize Camillo Procaccini as a major protagonist of late Mannerism in Northern Italy, particularly in Milan. His technical proficiency, especially in fresco, is widely acknowledged, as is his ability to convey intense religious emotion suitable for the Counter-Reformation era. He successfully led a major family workshop, contributing significantly to the artistic production of Lombardy for decades.

However, his critical evaluation is sometimes tempered. While respected for his skill and productivity, some critics argue that his work, compared to the greatest masters of his time like the Carracci or the emerging Baroque innovators, occasionally lacks profound originality or the highest level of artistic depth. His adherence to Mannerist formulas, while expertly handled, can sometimes feel repetitive or overly stylized to modern eyes. His art is often seen as representing the skillful culmination of Mannerism rather than the pioneering spirit of the nascent Baroque.

Despite these nuances, his historical importance is undeniable. He was a dominant figure in Milanese art for decades, a master of large-scale decoration, and a key interpreter of Counter-Reformation ideology through the lens of late Mannerism. His work provides a crucial link between the Renaissance tradition and the developing Baroque style in Lombardy.

Conclusion: An Enduring Milanese Master

Camillo Procaccini remains a vital figure for understanding the art of late sixteenth and early seventeenth-century Italy. As the leader of the Procaccini family workshop, he dominated the Milanese art scene, producing a vast body of work characterized by Mannerist elegance, dramatic intensity, and Counter-Reformation piety. Trained in Bologna, refined in Rome, and flourishing in Milan, he synthesized various influences into a distinctive and influential style. While perhaps not reaching the revolutionary heights of some contemporaries, his skill, productivity, and impact on Lombard art secure his place as a significant master of his era.

Where to Experience Procaccini's Art

Works by Camillo Procaccini can be found in numerous churches and museums across Italy and internationally. Key locations include:

Milan: Pinacoteca di Brera, Pinacoteca del Castello Sforzesco, Milan Cathedral (Duomo), Basilica di San Sepolcro, Church of San Vittore al Corpo, Church of Sant'Angelo.

Italy: Piacenza Cathedral, Museo Civico di Cremona, churches in Reggio Emilia.

United States: National Gallery of Art (Washington, D.C.), The Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York), Blanton Museum of Art (Austin, Texas).

Brazil: National Museum of Fine Arts (Rio de Janeiro).

Many of his most significant works, particularly his fresco cycles, remain in situ in the churches and buildings for which they were originally created, offering the most authentic experience of his artistic vision within its intended context.