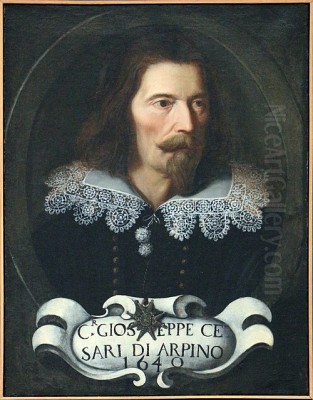

Giuseppe Cesari (1568-1640), widely known during his lifetime and beyond as the Cavaliere d'Arpino, stands as one of the most prominent and prolific painters active in Rome during the transitional period between the High Renaissance and the burgeoning Baroque era. Born in Arpino, a town then part of the Kingdom of Naples, Cesari rose to extraordinary fame and influence, particularly under papal patronage. His distinctive style, deeply rooted in the tenets of late Mannerism, dominated the Roman art scene for decades, even as revolutionary figures like Caravaggio began to challenge the established aesthetic norms. Cesari's extensive work, primarily large-scale frescoes and altarpieces, adorned numerous churches and palaces, solidifying his reputation as a leading master of his time.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Rome

Giuseppe Cesari was born in 1568, likely in Arpino, although some sources suggest Rome. His father, Muzio Cesari, was also a painter, described as being of humble origins, suggesting that Giuseppe's artistic inclinations may have been nurtured from a young age. A pivotal moment occurred around 1582 when, at the tender age of approximately fourteen, Giuseppe accompanied his mother to Rome. The city, undergoing significant urban and artistic transformation under popes like Gregory XIII, offered fertile ground for ambitious young artists.

Upon arriving in Rome, Cesari's talent was quickly recognized. He entered the workshop of Nicolò Circignani, known as Il Pomarancio, a painter favored for large decorative cycles. Circignani was heavily involved in the extensive decorations commissioned by Pope Gregory XIII for the Vatican Palace, particularly in the Logge. Cesari initially joined the workshop possibly as a garzone or assistant, involved in preparatory tasks like grinding pigments or preparing surfaces. However, his precocious skill, especially in drawing and composition, did not go unnoticed for long.

His rapid ascent is remarkable. Within a short period, he transitioned from a mere assistant to a contributing artist within Circignani's team working on the Vatican Logge. This early exposure to large-scale fresco projects and the competitive environment of papal commissions proved formative. It allowed him to hone his technical skills, particularly in the demanding medium of fresco, and to absorb the prevailing artistic currents of late Roman Mannerism, characterized by artists like Federico Zuccari and Cesare Nebbia, who emphasized intricate compositions, elegant figures, and decorative richness.

Ascendancy under Papal Patronage

Cesari's career trajectory soared under the patronage of successive popes, beginning significantly with Pope Clement VIII (reigned 1592-1605). His talent for creating grand, complex, and visually appealing compositions perfectly suited the representational needs of the papacy and the Roman aristocracy. He became one of the most sought-after artists in Rome, managing a large and productive workshop to handle the numerous commissions he received.

Under Clement VIII, Cesari undertook several prestigious projects. He was heavily involved in the decoration of the Lateran Palace and the Quirinal Palace. His work was highly esteemed by the Pope, who, in recognition of his artistic achievements and service, bestowed upon him the title of Cavaliere di Cristo (Knight of Christ) around 1600. This honorific, from which his moniker "Cavaliere d'Arpino" derives, significantly elevated his social standing and further cemented his professional success. He was no longer just Giuseppe Cesari, but the esteemed Knight of Arpino.

His favor continued, albeit perhaps with less intensity, under subsequent popes like Paul V and Gregory XV. For Gregory XV, he contributed to the decoration of ceilings within the Vatican Palace. His workshop became a major force in Roman art production, attracting numerous pupils and assistants who helped execute his designs for vast decorative schemes. This period marked the zenith of his fame and influence, making him arguably the most powerful painter in Rome around the turn of the 17th century.

Major Commissions and Representative Works

The Cavaliere d'Arpino's oeuvre is vast, dominated by large-scale fresco cycles and significant altarpieces, primarily located in Rome. One of his most significant and enduring contributions was his work for St. Peter's Basilica. Between approximately 1603 and 1612, he was commissioned to provide the cartoons (preparatory designs) for the mosaics decorating the interior of Michelangelo's great dome. This was a commission of immense prestige, placing Cesari at the heart of the most important church in Christendom. The mosaics, depicting saints and heavenly hierarchies, reflect his characteristic style translated into the demanding medium of mosaic.

Cesari's frescoes adorn numerous Roman churches. He executed important cycles in the Olgiati Chapel in Santa Prassede, demonstrating his skill in narrative composition and elegant figural representation. He also worked in San Luigi dei Francesi, the French national church in Rome, notably contributing frescoes to the vault of the famous Contarelli Chapel, whose wall paintings are masterpieces by Caravaggio. This juxtaposition highlights the stylistic crossroads of the era. Further commissions included work for Santa Maria in Vallicella (Chiesa Nuova), where his St. Lawrence Distributing Alms can be found, and decorations for various chapels and institutions like the Ospizio di San Rocco, San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane, Ospizio di Santa Lucia in Suburra, Ospizio di Santa Cecilia in Trastevere, and Ospizio di San Matteo in Sapienza.

Beyond frescoes, Cesari was also a prolific painter of easel pictures, often on panel or canvas, but sometimes on more precious materials like copper or lapis lazuli. Mythological and religious subjects dominate. Notable examples include the Expulsion of Adam and Eve from Paradise and a Madonna and Child, both now housed in the Louvre Museum, Paris. His Perseus and Andromeda, painted on lapis lazuli, exists in versions held by the Louvre and the St. Louis Art Museum, showcasing his ability to work on a small, detailed scale with precious materials. The Borghese Gallery in Rome holds several of his works, including Venus Crowned by Cupid, which entered the collection after a dramatic confiscation. An early work, Fame, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, demonstrates his skill in mixed media.

Artistic Style: The Epitome of Late Mannerism

The Cavaliere d'Arpino's style is the quintessential expression of late Roman Mannerism, often referred to as the Maniera. This style, which evolved from the High Renaissance ideals of artists like Raphael and Michelangelo, emphasized elegance, grace, complexity, and a certain artificiality over naturalism. Cesari's figures are typically elongated, posed in elegant, often complex contrapposto or serpentine twists. Compositions are crowded and intricate, filled with figures and decorative details, prioritizing visual richness and sophistication.

His color palette is often vibrant, sometimes employing the acidic or shot colors characteristic of Mannerism, though it could also tend towards a more enamel-like smoothness. While capable of conveying emotion, the overall effect is often one of refined detachment rather than raw, visceral feeling. This emphasis on grazia (grace) and facilità (ease of execution, concealing effort) was highly valued by the sophisticated patrons of the time. He possessed a remarkable facility for drawing (disegno), which formed the foundation of his compositions. Some sources mention a detailed, almost Flemish-like technique in his smaller works, suggesting an appreciation for meticulous finish.

However, Cesari's adherence to the Mannerist idiom also drew criticism, particularly as the artistic climate began to shift towards the Baroque. The influential art theorist Giovanni Pietro Bellori, a proponent of the classical-idealist Baroque style championed by the Carracci, criticized Cesari's work for being overly reliant on established formulas and lacking in naturalism and emotional depth. Bellori found his style too "mannered," prioritizing fantasy and convention over the study of nature. Indeed, compared to the revolutionary naturalism and dramatic chiaroscuro of Caravaggio, or the robust classicism of Annibale Carracci, Cesari's work could appear somewhat retardataire, clinging to an older aesthetic. Some critics also pointed to occasional weaknesses in anatomical rendering or perspective, suggesting that the sheer volume of his output sometimes led to a reliance on workshop execution and standardized figures.

The Workshop, Collaborators, and Influence

Like many successful artists of his era, the Cavaliere d'Arpino operated a large and highly organized workshop. This was essential to manage the scale and number of commissions he received, particularly for extensive fresco cycles. The workshop served as a training ground for numerous younger artists and employed assistants who specialized in different aspects of production, from transferring cartoons to painting backgrounds or secondary figures, all under Cesari's supervision and based on his designs.

Among his collaborators, Cesare Rossetti is mentioned as a close associate who assisted him on significant fresco projects. The workshop was known not only for large-scale figurative works but also, according to some accounts related to Caravaggio's early career, for producing decorative elements like flowers and fruit, suggesting a diverse output catering to various market demands.

Cesari's influence during his peak years was immense. As the dominant painter in Rome, his style set the standard for official commissions and was widely imitated. He held prestigious positions within the artistic community, including serving as Principe (President) of the Accademia di San Luca, Rome's official artists' academy, in 1605 and again later. This role placed him at the center of artistic life, influencing teaching and professional standards. His success provided a model for achieving fame and fortune through art, particularly via papal patronage.

The Complex Relationship with Caravaggio

One of the most fascinating aspects of Cesari's career is his connection to Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio. Around 1592, the young and relatively unknown Caravaggio arrived in Rome from Lombardy and, for a period variously estimated from several months to a couple of years, worked in the Cavaliere d'Arpino's bustling studio. Accounts suggest Caravaggio was employed primarily to paint still lifes of flowers and fruit, elements for which Cesari's workshop apparently had a demand, perhaps incorporated into larger decorative schemes or sold as independent pieces.

This period undoubtedly exposed Caravaggio to the workings of a highly successful Roman workshop and the prevailing Mannerist style. Some art historians detect subtle influences of Cesari's detailed approach or compositional elements in Caravaggio's very early works. However, the association was relatively brief, and Caravaggio soon left Cesari's employ, possibly due to illness, disagreement, or simply the desire to pursue his own radical artistic path.

Stylistically, the two artists represent opposing poles of Roman painting around 1600. Cesari embodied the established, elegant, and somewhat artificial Maniera, favored by the establishment. Caravaggio became the revolutionary proponent of a dramatic, unidealized naturalism, using strong chiaroscuro (contrasts of light and dark) and drawing models directly from life, often from the lower classes. Cesari, despite this direct contact, remained largely untouched by Caravaggio's stylistic innovations, continuing firmly in his Mannerist path. Their relationship may also have been tinged with rivalry, especially as Caravaggio's star began to rise, challenging the Cavaliere's dominance. Later events, including accusations surrounding a 1607 incident, suggest lingering animosity.

Patrons, Prestige, and Shifting Fortunes

The Cavaliere d'Arpino's success was built on a foundation of powerful patronage. Popes Gregory XIII, Clement VIII, Paul V, and Gregory XV all employed him, with Clement VIII being perhaps his most significant supporter, granting him the knighthood that became his trademark. Beyond the papacy, he worked for influential families like the Contarelli (patrons of the famous chapel in San Luigi dei Francesi) and various religious confraternities and institutions, such as the Confraternita dei Pellegrini e Convalescenti and the Compagnia di San Giuseppe in Terrasanta. His works permeated the fabric of ecclesiastical Rome.

His leadership role in the Accademia di San Luca further solidified his status. He was, for a time, the arbiter of taste and the most successful painter in the city. However, artistic fortunes could be tied to political ones. The death of his main patron, Clement VIII, in 1605 marked a turning point. While he continued to receive commissions, his pre-eminence began to be challenged by the rising tide of the Baroque, represented by Caravaggio's followers and the Bolognese school led by the Carracci and their pupils like Guido Reni and Domenichino.

His later career was also marred by controversy. In 1607, Cesari faced serious legal trouble. Accounts differ slightly: some mention an arrest for forgery, while others connect it to an accusation, possibly instigated by rivals including Caravaggio, concerning the illegal possession of firearms (arquebuses). This incident led to the confiscation of his impressive personal collection of paintings by Pope Paul V. These paintings were subsequently given to the Pope's nephew, Cardinal Scipione Borghese, a voracious collector and patron of artists like Bernini. This event significantly enriched the Borghese collection with works by Cesari himself and possibly other masters he owned, while simultaneously marking a downturn in the Cavaliere's personal fortunes and perhaps his standing. Although he was released and continued to work, his undisputed dominance had waned.

Later Life, Legacy, and Major Collections

Despite the controversies and the shifting artistic tides, the Cavaliere d'Arpino remained active and respected until his death in Rome on July 3, 1640. He continued to receive commissions, adapting his style slightly perhaps, but fundamentally remaining true to his Mannerist roots. His prolific output ensured his enduring presence in Rome's artistic landscape.

His legacy is complex. He represents the final flowering of Mannerism in Rome, a style of great sophistication and decorative appeal. For decades, he defined the mainstream of official painting. His workshop trained numerous artists, disseminating his style. However, his resistance to the burgeoning naturalism and dynamism of the Baroque meant that his direct stylistic influence on the next generation was limited compared to figures like Caravaggio or Annibale Carracci. He is often seen as a talented, highly successful, but ultimately conservative figure who upheld tradition in an age of revolution. Yet, the sheer quality and ubiquity of his work make him an indispensable figure for understanding Roman art around 1600.

Today, Giuseppe Cesari's works are found in major collections worldwide, although the bulk remains in Rome. Key institutions housing his paintings include:

Galleria Borghese, Rome: Holds a significant collection, partly due to the 1607 confiscation, including Venus Crowned by Cupid and works attributed to Caravaggio from his time in Cesari's studio.

Vatican Museums, Rome: Features his work in various decorative contexts, including designs for the St. Peter's dome mosaics.

Uffizi Gallery, Florence: Possesses paintings, including a self-portrait and the portrait drawing of Cristoforo Roncalli.

Louvre Museum, Paris: Houses important works like the Expulsion of Adam and Eve and Perseus and Andromeda.

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York: Holds the early work Fame.

St. Louis Art Museum: Features a version of Perseus Rescuing Andromeda.

Real Academia de Bellas Artes de Santa Isabel de Hungría, Seville: Contains an example of his oil painting.

Numerous churches in Rome, including Santa Prassede, San Luigi dei Francesi, Santa Maria in Vallicella, and others mentioned previously, still preserve his extensive fresco decorations and altarpieces in situ.

Conclusion

Giuseppe Cesari, the Cavaliere d'Arpino, was a towering figure in Roman art at the cusp of the 17th century. His career exemplifies extraordinary success achieved through talent, ambition, and navigating the complex world of papal patronage. As a leading master of Late Mannerism, he produced an enormous body of work characterized by elegance, complexity, and decorative richness, shaping the visual environment of Rome for decades. While his style was eventually eclipsed by the dynamism and naturalism of the Baroque, spearheaded by artists like Caravaggio and the Carracci, Cesari's historical importance is undeniable. His paintings and frescoes remain crucial testimonies to the artistic tastes and cultural climate of Rome during a pivotal moment of transition, and his life story, intertwined with figures like Caravaggio and powerful popes, offers a fascinating glimpse into the competitive and vibrant art world of his time.