Carl Blechen stands as a significant, if sometimes underappreciated, figure in the landscape of 19th-century German art. Bridging the gap between the profound spiritualism of Romanticism and the burgeoning tenets of Realism, Blechen's work offers a unique vision of nature, imbued with both dramatic intensity and a keen observational acuity. His relatively short but impactful career left a legacy of paintings and sketches that continue to fascinate for their innovative use of light, color, and composition, marking him as a critical transitional artist.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

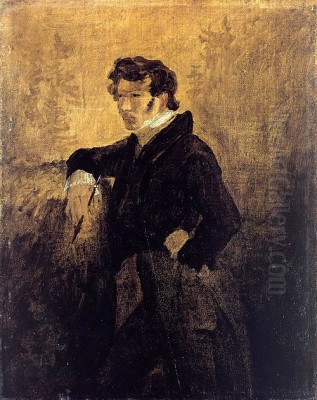

Born Carl Eduard Ferdinand Blechen on July 29, 1798, in Cottbus, then a town in the Prussian Province of Brandenburg (now part of Berlin), his early life did not immediately point towards a career in the arts. His initial training was in commerce, and he dutifully pursued this path, working in a bank from 1815 for several years. This practical, business-oriented background seems a world away from the evocative landscapes he would later create.

However, the call of art proved too strong to ignore. By 1822, Blechen made a decisive shift, enrolling at the prestigious Berlin Academy of Arts (Königliche Akademie der Künste). This institution was a crucible for artistic talent in Prussia, and it was here that Blechen began to formally hone his skills as a painter. His decision to abandon a secure, if perhaps unfulfilling, career in banking for the uncertain life of an artist speaks to a deep-seated passion and a compelling inner drive.

Formative Years and Influences

At the Berlin Academy, Blechen immersed himself in the study of landscape painting. The artistic environment in Berlin and other German cultural centers was rich and varied. Romanticism, with its emphasis on emotion, individualism, and the sublime power of nature, was a dominant force. Figures like Caspar David Friedrich, with his spiritually charged and meticulously rendered landscapes, had already established a powerful precedent.

A crucial experience for Blechen occurred in the summer of 1823 when he undertook an artistic study trip to Dresden. This city was another major hub of German Romanticism. It was here that Blechen had the significant opportunity to meet two leading figures of the movement: the aforementioned Caspar David Friedrich and the Norwegian-born painter Johan Christian Dahl. Dahl, who had settled in Dresden, was known for his more naturalistic and dynamic approach to landscape, often capturing wild, untamed scenery. The encounter with these artists undoubtedly left a profound impression on the young Blechen, exposing him to different facets of Romantic landscape painting and likely encouraging his own explorations.

During this period, Blechen also came into contact with the influential architect and painter Karl Friedrich Schinkel. Schinkel was a towering figure in Prussian cultural life, known for his neoclassical and neo-Gothic architectural designs, but also a talented painter and stage designer. Schinkel recognized Blechen's talent and became an important supporter. This connection would prove beneficial, as Schinkel's influence extended to securing Blechen a position as a stage designer at the Königstädtisches Theater in Berlin from 1824 to 1827. This experience with theatrical design, with its emphasis on dramatic lighting and evocative settings, likely contributed to the sense of drama and atmosphere found in his later landscape paintings.

Other artists active in the German-speaking world at this time, contributing to the rich artistic milieu, included Philipp Otto Runge, whose work explored symbolic and mystical themes within Romanticism, and Carl Gustav Carus, a physician, philosopher, and painter who was a friend of Friedrich and also explored the spiritual dimensions of nature. While direct interaction with all these figures isn't always documented for Blechen, their collective work formed the artistic atmosphere he navigated.

The Italian Sojourn: A Turning Point

A pivotal moment in Blechen's artistic development was his journey to Italy, undertaken between 1828 and 1829. For centuries, Italy had been a magnet for artists from across Europe, drawn by its classical ruins, Renaissance masterpieces, and, crucially for landscape painters, its unique light and varied scenery. Blechen's Italian experience was transformative, pushing his art in a new direction.

In Italy, Blechen was exposed to a different quality of light – brighter, clearer, and more intense than the often more muted light of Northern Europe. He traveled extensively, sketching and painting directly from nature. This practice of en plein air (outdoor) sketching, though not entirely new, was gaining traction and was crucial for capturing the fleeting effects of light and atmosphere. His Italian works show a heightened sensitivity to these effects, with a warmer palette and a more fluid, spontaneous brushwork.

The landscapes of Italy, from the Roman Campagna to the coastal regions around Naples and Amalfi, provided him with a wealth of new subjects. He was less interested in the idealized, classical landscapes favored by some of his predecessors and contemporaries, like Joseph Anton Koch, an Austrian painter who was a leading figure among German artists in Rome. Instead, Blechen often focused on the more rugged, everyday aspects of the Italian scene, or on capturing the dramatic interplay of light and shadow on ancient ruins or natural formations. This direct engagement with the visual reality of Italy began to temper the more overtly Romantic elements in his work, steering him towards a greater naturalism, a precursor to Realism.

His Italian sketches and paintings, such as Gorge near Amalfi or studies of Tivoli, reveal this shift. They are characterized by a freshness and immediacy, a sense of capturing a specific moment in time and place. This experience in Italy was instrumental in developing his signature style, which combined Romantic sensibility with a more objective observation of the natural world.

Professorship and Mature Style

Upon his return to Germany, Blechen's reputation continued to grow. The impact of his Italian studies was evident in his work, which now displayed a greater confidence in handling light and color, and a more direct approach to landscape. In 1831, a significant professional milestone was reached when he was appointed Professor of Landscape Painting at the Berlin Academy of Arts. He succeeded Peter Ludwig Lütke in this role, and it's noted that Karl Friedrich Schinkel was instrumental in this appointment, further highlighting Schinkel's belief in Blechen's abilities.

As a professor, Blechen was in a position to influence a new generation of artists. His own work during the 1830s continued to evolve. While the dramatic and sometimes melancholic undertones of Romanticism remained, his paintings increasingly demonstrated a commitment to capturing the tangible reality of the scenes before him. He developed a free, broad, and expressive brushstroke, often using impasto to convey texture and a vibrant sense of light.

His landscapes from this period often feature strong contrasts of light and shadow, creating a sense of dynamism and sometimes unease. He was not afraid to depict scenes of industry, such as Rolling Mill in Eberswalde, which was quite innovative for its time, showing an interest in the changing face of the landscape due to industrialization, a theme that would be more fully explored by later Realist painters like Adolph Menzel (though Menzel's main industrial scenes came later, Blechen was an early adopter of such subjects).

Blechen's color palette became richer and more nuanced, often employing warm earth tones, vibrant greens, and luminous blues. He had a remarkable ability to convey the specific atmosphere of a place, whether it was the humid interior of a greenhouse, the sun-drenched ruins of an Italian landscape, or the moody depths of a German forest.

Key Works and Artistic Characteristics

Carl Blechen's oeuvre, though not vast due to his relatively short life, contains several masterpieces that exemplify his unique artistic vision.

One of his most famous works is Das Inneres des Palmenhauses auf der Pfaueninsel bei Potsdam (Interior of the Palm House on Peacock Island near Potsdam), painted around 1832-1834. This painting depicts the exotic interior of a large greenhouse, filled with lush tropical plants. Blechen masterfully captures the interplay of light filtering through the glass roof, illuminating the dense foliage and creating a humid, almost palpable atmosphere. The work is a tour-de-force of light and color, showcasing his ability to render complex textures and a sense of enclosed space, while also hinting at the Romantic fascination with the exotic and the artificial paradise.

Another significant work is Im Park der Villa d'Este (In the Park of the Villa d'Este), painted around 1830. This painting, inspired by his Italian journey, depicts the famous gardens of the Villa d'Este in Tivoli, known for their elaborate fountains and ancient cypress trees. Blechen focuses on the dramatic contrasts of light and shadow, the play of sunlight on stone and foliage, and the sense of history embedded in the landscape. It combines a Romantic appreciation for the picturesque with a more direct, observational approach.

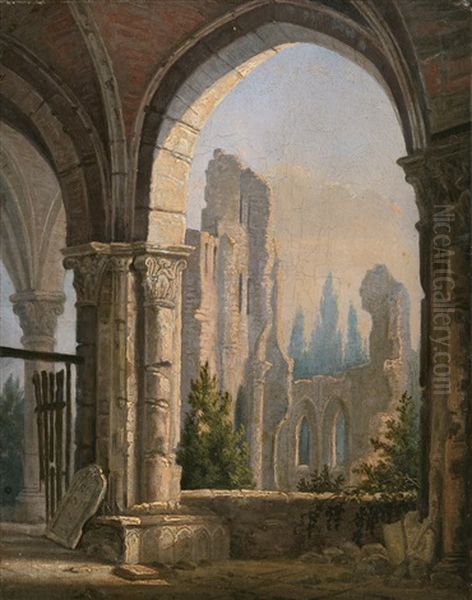

His German landscapes, such as Waldinneres mit Bach (Forest Interior with Stream) or Gotische Kirchenruine (Gothic Church Ruin), often convey a sense of melancholy or the sublime. He was adept at capturing the dense, mysterious quality of German forests, or the poignant beauty of ruins reclaimed by nature. These works connect him to the broader Romantic tradition of artists like Friedrich or Ernst Ferdinand Oehme, who also explored themes of decay, transience, and the spiritual in nature.

Blechen's artistic style is characterized by several key features:

1. Dramatic Use of Light and Shadow (Chiaroscuro): He employed strong contrasts to create mood, depth, and focus attention. Light in his paintings is often active and transformative.

2. Expressive Brushwork: His brushstrokes are often visible, energetic, and contribute to the overall texture and dynamism of the painting. This freeness was quite modern for its time.

3. Rich and Warm Color Palette: Particularly after his Italian journey, his colors became more vibrant and luminous, though he could also masterfully use more subdued tones for specific atmospheric effects.

4. Fusion of Romanticism and Realism: While his subjects often had Romantic overtones (ruins, wild nature, dramatic weather), his approach to rendering them showed an increasing concern for visual accuracy and the specific character of a place. He sought to capture the "truth" of nature as he observed it, filtered through his artistic sensibility.

5. Atmospheric Depth: Blechen excelled at creating a palpable sense of atmosphere, whether it was the humid air of a palm house, the crisp light of an Italian morning, or the misty depths of a forest.

His oil sketches are particularly noteworthy for their spontaneity and freshness, revealing his direct engagement with nature and his experimental approach to capturing light and color. These sketches often possess a modernity that anticipates later movements like Impressionism, though he remained rooted in the concerns of his own era.

Thematic Concerns and Romantic Sensibilities

While Blechen moved towards a more realistic depiction of landscape, his work remained deeply imbued with Romantic sensibilities. He was not merely a topographical painter; his landscapes are often charged with emotion and psychological depth.

The theme of nature's power and grandeur is recurrent. This can be seen in his depictions of stormy skies, rugged mountains, or dense, untamed forests. There's often a sense of the sublime, an awareness of humanity's smallness in the face of nature's vastness, a common trope in Romantic art, famously explored by painters like J.M.W. Turner in England, whose dramatic seascapes and atmospheric effects, while distinct, share a certain Romantic intensity with Blechen's work.

Ruins, both classical and medieval, feature prominently in his paintings. For the Romantics, ruins symbolized the passage of time, the transience of human endeavors, and the enduring power of nature. Blechen's ruins are not just picturesque elements; they often evoke a sense of melancholy, history, and reflection.

There is also a darker, more unsettling undercurrent in some of his works. His landscapes can sometimes feel brooding or mysterious, hinting at hidden forces or a sense of unease. This aligns with the "Schauerromantik" or Gothic Romanticism, an aspect of the movement that explored the uncanny, the irrational, and the terrifying. This "darker" side of Blechen's Romanticism, sometimes with a touch of the grotesque or ironic, distinguished him from the more serene or overtly spiritual landscapes of some of his contemporaries.

His interest in industrial scenes, like the Rolling Mill, also suggests a Romantic engagement with the changing world. While some Romantics lamented the encroachment of industry on nature, others were fascinated by its raw power and visual drama – the fire, smoke, and monumental machinery. Blechen seems to approach these subjects with a degree of objective fascination, capturing their visual impact without overt moralizing.

Connections and Contemporaries in the Broader Art World

Blechen's artistic journey unfolded within a dynamic European art scene. In Germany, the Biedermeier period (roughly 1815-1848) overlapped with late Romanticism and early Realism. Biedermeier art often emphasized domesticity, sentiment, and a more intimate, less heroic view of the world. While Blechen's dramatic landscapes don't fit neatly into the Biedermeier category, the period's growing interest in everyday reality and detailed observation can be seen as part of the broader cultural shift towards Realism that influenced him. Artists like Adrian Ludwig Richter became famous for their idyllic Biedermeier scenes and illustrations.

In Austria, Ferdinand Georg Waldmüller was a leading figure who, like Blechen, moved from a more idealized style towards a greater naturalism and meticulous observation of light, particularly in his landscapes and genre scenes. Though working in a different cultural center, Waldmüller's trajectory shares some parallels with Blechen's increasing focus on direct observation.

The Düsseldorf school of painting was also gaining prominence in Germany, known for its detailed and often narrative-driven landscapes and historical scenes. Artists like Andreas Achenbach became famous for their dramatic seascapes and landscapes, often with a high degree of finish. Blechen's looser, more expressive style set him apart from the meticulousness of some Düsseldorf painters, though he shared their interest in capturing the power of nature.

In France, the Barbizon School was emerging around the 1830s, with artists like Théodore Rousseau and Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot advocating for painting directly from nature and focusing on realistic depictions of the French countryside. While Blechen's direct connections to the Barbizon painters are not well-documented, his emphasis on en plein air sketching and his move towards a more naturalistic landscape align with the broader European trend they represented. Corot, in particular, also spent significant time in Italy, and his Italian landscapes share a similar freshness and sensitivity to light as Blechen's.

The English landscape tradition, with giants like John Constable and J.M.W. Turner, had also made significant strides in the early 19th century. Constable's commitment to capturing the specific atmospheric conditions of his native Suffolk and his scientific observation of clouds and light resonated with the growing interest in naturalism across Europe.

Blechen's position as a professor at the Berlin Academy placed him at the heart of artistic discourse in Prussia. His students would have been exposed to his evolving style and his emphasis on direct observation combined with artistic interpretation. While his direct pedagogical lineage is a subject for deeper art historical research, his influence would have been felt within the Academy's circles.

Later Years and Tragic Decline

Despite his professional success and artistic innovations, Carl Blechen's later years were marked by tragedy. From the mid-1830s onwards, his mental health began to deteriorate significantly. He suffered from severe bouts of depression and increasing psychological distress. This debilitating condition gradually made it impossible for him to continue his work as a painter and as a professor.

The exact nature of his mental illness is, of course, difficult to diagnose retrospectively, but contemporary accounts describe periods of deep melancholy and erratic behavior. By 1836, his condition had worsened to the point where he had to take a leave of absence from his teaching duties at the Academy. His artistic output dwindled as his illness took hold.

This decline was a profound loss for the German art world, as Blechen was at the height of his artistic powers. His unique vision, which so effectively blended Romantic feeling with a keen observational eye, was silenced prematurely. He spent his final years struggling with his mental affliction.

Carl Blechen died on July 23, 1840, in Berlin, just shy of his 42nd birthday. He passed away in a state of mental derangement, a tragic end to a life that had contributed so much to German art. He was buried in the Dreifaltigkeitskirchhof II cemetery in Berlin-Kreuzberg.

Legacy and Historical Reassessment

For a considerable time after his death, Carl Blechen's work was somewhat overlooked, particularly outside of Germany. The prevailing tastes of the mid to late 19th century often favored more polished, academic styles or the grand narratives of history painting. The raw energy and sometimes unsettling qualities of Blechen's art did not always align with these preferences.

However, the early 20th century saw a renewed interest in German Romanticism and a re-evaluation of artists from that period. Art historians and critics began to recognize Blechen's innovative contributions and his pivotal role as a transitional figure. The Berlin Nationalgalerie played a significant role in this rediscovery, notably with a major exhibition in 1906 curated by Hugo von Tschudi, which helped to bring Blechen's work to a wider audience and solidify his importance.

Today, Carl Blechen is recognized as one of the most important German landscape painters of the early 19th century, often ranked alongside figures like Caspar David Friedrich and Johan Christian Dahl in terms of his originality and influence. His ability to infuse landscapes with psychological depth while simultaneously pushing towards a more direct, realistic mode of representation marks him as a singularly important artist.

His influence can be seen in the development of German Realism. His willingness to tackle unconventional subjects, like industrial scenes, and his emphasis on capturing the specific character of a place, paved the way for later artists who would more fully embrace Realist principles. His expressive brushwork and bold use of color also anticipated later artistic developments.

Museums across Germany and internationally now hold his works, with significant collections in Berlin (Alte Nationalgalerie, Kupferstichkabinett), Dresden (Galerie Neue Meister, Kupferstich-Kabinett), and his birthplace, Cottbus (Brandenburgisches Landesmuseum für moderne Kunst). His paintings and, importantly, his numerous oil sketches and drawings continue to be studied and admired for their artistic power and historical significance.

Conclusion

Carl Blechen's art offers a compelling journey through the shifting artistic landscape of early 19th-century Germany. From his roots in Romanticism, with its emphasis on emotion and the sublime, he forged a path towards a more direct and unvarnished engagement with the natural world, heralding the rise of Realism. His Italian sojourn was a critical catalyst in this development, imbuing his work with a new luminosity and immediacy.

Despite a career cut short by tragic illness, Blechen left behind a body of work characterized by its dramatic intensity, innovative technique, and profound sensitivity to the nuances of light and atmosphere. His landscapes are more than mere depictions of scenery; they are evocative explorations of mood, place, and the complex interplay between the human spirit and the natural world. As an artist who dared to look at nature with fresh eyes, and to translate his vision with a bold and expressive hand, Carl Blechen remains a vital and enduring figure in the history of art.