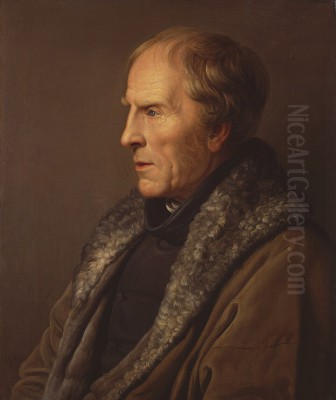

Caspar David Friedrich stands as the preeminent figure of 19th-century German Romantic painting. Born in Greifswald, a harbour town in Pomerania (then Swedish, later Prussian, now Germany) on September 5, 1774, he became renowned for his atmospheric landscape paintings that prioritized spiritual and emotional depth over mere topographical accuracy. His work is characterized by its contemplative mood, symbolic richness, and profound engagement with nature as a conduit to the divine. Though his fame waned in his later years, Friedrich was rediscovered in the early 20th century and is now celebrated as a pivotal artist whose influence extends into modern art.

Early Life and Formative Experiences

Friedrich's upbringing in the strict Lutheran environment of Greifswald profoundly shaped his worldview and artistic sensibility. He was the sixth of ten children born to Adolf Gottlieb Friedrich, a candle-maker and soap boiler, and his wife Sophie Dorothea Bechly. His childhood was marked by a series of devastating personal tragedies that would cast a long shadow over his life and art. His mother died when he was just seven years old. Further losses followed: his sister Elisabeth died in 1781, another sister, Maria, succumbed to typhus in 1791.

Perhaps the most traumatic event occurred in 1787. While ice skating, Caspar David fell through the ice. His younger brother, Johann Christoffer, rushed to save him but tragically drowned in the attempt. Friedrich carried the weight of this incident, possibly compounded by feelings of guilt, throughout his life. These early encounters with death and loss are widely believed to have contributed to the pervasive themes of melancholy, solitude, mortality, and the search for spiritual solace found in his mature work.

Artistic Education and Influences

Friedrich began his formal artistic studies in 1790 at the University of Greifswald, which maintained a small arts faculty. His drawing teacher there was Johann Gottfried Quistorp, an architect and painter who followed the pedagogical ideas of Johann Georg Sulzer. Quistorp introduced Friedrich to outdoor sketching and encouraged a close observation of nature, fostering the young artist's innate connection to the landscape of his homeland. Quistorp also likely introduced Friedrich to the theology of Ludwig Gotthard Kosegarten, a local pastor and poet who preached that nature was a revelation of God, a concept that became central to Friedrich's art.

In 1794, Friedrich continued his education at the prestigious Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen, one of the most liberal art academies in Europe at the time. There, he studied under teachers such as the landscape painter Christian August Lorentzen, the portraitist and landscapist Jens Juel, and the influential history painter Nicolai Abildgaard. While the Academy emphasized drawing from plaster casts and life models in the Neoclassical tradition, Copenhagen also exposed Friedrich to the burgeoning ideas of Romanticism, particularly the German Sturm und Drang (Storm and Stress) movement, which valued subjective emotion and intuition over rationalism.

Settling in Dresden and Early Career

After completing his studies in Copenhagen in 1798, Friedrich settled permanently in Dresden, the vibrant capital of Saxony and a major centre for the German Romantic movement. He quickly became associated with a circle of artists and intellectuals, including the painter Gerhard von Kügelgen. Initially, he worked primarily in ink, watercolour, and sepia, producing meticulously detailed drawings of the Saxon landscape, the Baltic coast, and the Harz Mountains. These early works already displayed his characteristic precision and his interest in natural forms like trees, rocks, and ruins.

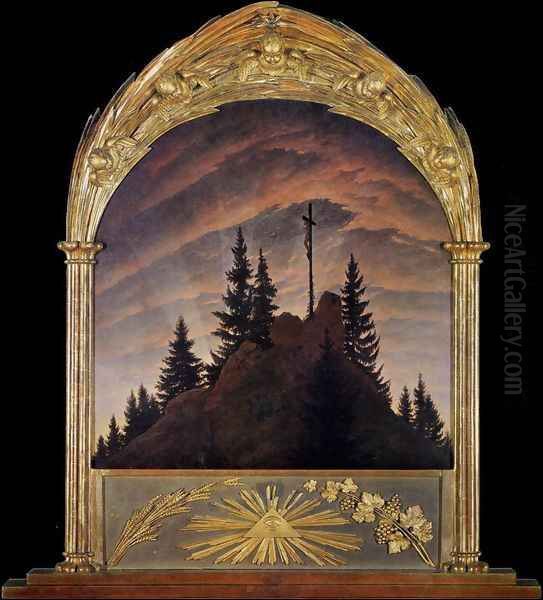

His transition to oil painting occurred around 1807. He gained significant public attention, and considerable controversy, with his first major oil painting, Cross in the Mountains (1807-08), also known as the Tetschen Altar. Commissioned as an altarpiece for a private chapel, its depiction of a crucifix atop a mountain peak, rendered as a pure landscape without traditional religious figures, challenged conventions and sparked a debate about the appropriateness of landscape painting for devotional purposes. The critic Basilius von Ramdohr fiercely attacked the work, arguing it was a misuse of landscape and bordered on sacrilege. Friedrich defended his work, articulating his belief that nature itself could convey profound spiritual meaning.

The Romantic Vision: Style and Themes

Friedrich's art is synonymous with German Romanticism's spiritual interpretation of nature. He sought to depict not just the external appearance of the landscape, but the human soul's response to it – what he termed Seelenlandschaft (soul landscape). His paintings are rarely straightforward depictions of specific locations; instead, they are carefully composed studio creations based on numerous outdoor sketches, synthesized to evoke a particular mood or idea. He famously advised artists to "close your physical eye so that you may see your picture first with the spiritual eye. Then bring what you saw in the dark to the light so that it may react upon others from the outside inwards."

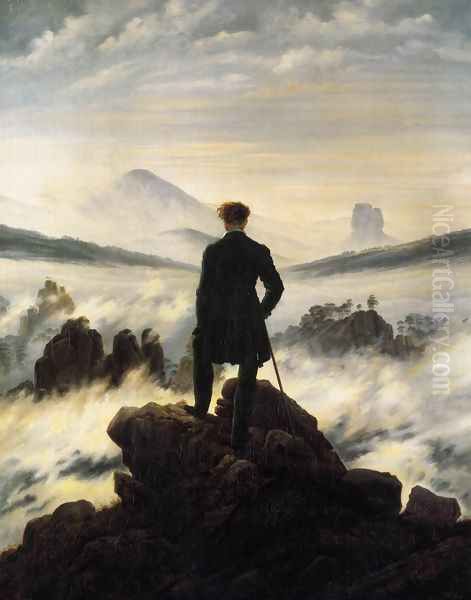

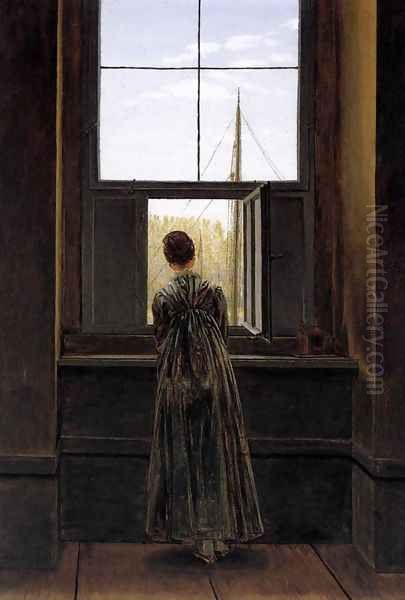

A recurring motif in Friedrich's work is the Rückenfigur, a figure seen from behind, contemplating the vastness of nature. This figure acts as a surrogate for the viewer, inviting them to participate in the act of contemplation and emphasizing the insignificance of the individual against the sublime power of the natural world. Examples include the iconic Wanderer above the Sea of Fog (c. 1818) and Woman at a Window (1822).

Symbolism permeates his landscapes. Oak trees might represent endurance or pagan German history, while evergreen fir trees often symbolize Christian hope and eternal life. Gothic ruins evoke the transience of human endeavours and the passage of time. Ships can represent the journey of life, sometimes sailing towards a hopeful horizon, other times wrecked or lost in ice, symbolizing despair or the struggle against fate. Fog and mist, frequently present, suggest the mysterious boundary between the earthly and the divine, the known and the unknown. Light, particularly the transitional light of dawn and dusk, carries emotional weight, signifying hope, melancholy, or spiritual awakening.

His technique was meticulous and precise, often involving thin glazes of oil paint applied carefully to create smooth surfaces and subtle atmospheric effects. This detailed rendering, while contributing to the intensity of his images, contrasted sharply with the looser brushwork favoured by later movements like Impressionism, contributing to the decline of his reputation during his lifetime. The overall mood of his work is often one of silence, solitude, melancholy, and a profound sense of awe before the infinite.

Landmark Works and Controversies

Beyond the Tetschen Altar, Friedrich created numerous masterpieces that define his oeuvre and the Romantic era. The Monk by the Sea (1808-10) and Abbey in the Oakwood (1809-10) were exhibited together at the Berlin Academy in 1810 to great acclaim. The Monk by the Sea presents a stark, minimalist composition with a lone Capuchin monk facing a vast, dark sea under an oppressive sky, evoking feelings of existential solitude and the overwhelming power of nature. Abbey in the Oakwood depicts a funeral procession carrying a coffin towards the ruins of a Gothic abbey in a snow-covered oak forest at twilight, a powerful meditation on death, faith, and the passage of time.

Wanderer above the Sea of Fog (c. 1818) is perhaps his most famous painting. It shows a man in traditional German attire standing atop a rocky precipice, gazing out over a sea of fog from which mountain peaks emerge. The image perfectly encapsulates the Romantic themes of individual contemplation, the sublime experience of nature, and the human yearning for the infinite.

Chalk Cliffs on Rügen (c. 1818), painted shortly after his marriage to the much younger Caroline Bommer, offers a brighter, though still complex, vision. It depicts figures, possibly including Friedrich himself and his wife, looking out from dramatic white cliffs towards the sea, suggesting themes of life's journey, companionship, and the allure of the unknown.

The Sea of Ice (1823-24), also known as The Wreck of the Hope, is one of his most dramatic and chilling works. It portrays the shattered wreckage of a ship crushed by monumental shards of ice under a cold, unforgiving sky. Inspired by accounts of Arctic expeditions, the painting serves as a powerful allegory for human fragility, the destructive power of nature, and perhaps political or personal despair.

Other significant works include Man and Woman Contemplating the Moon (c. 1824), The Stages of Life (c. 1835), and Cloister Cemetery in the Snow (1817-19, now destroyed but known through reproductions), which revisited the themes of death and ruins seen in Abbey in the Oakwood.

Relationship with Contemporaries

Friedrich's singular vision sometimes brought him into conflict with other prominent figures. His relationship with Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, the towering figure of German literature and a keen amateur scientist, soured significantly. In 1816, Goethe asked Friedrich to contribute drawings of specific cloud formations for his meteorological studies. Friedrich, viewing the sky as a realm of divine mystery rather than scientific classification, reportedly refused or fulfilled the request reluctantly and inadequately, leading to a lasting estrangement. Goethe found Friedrich's intense focus on symbolism and melancholy increasingly alien.

Despite his somewhat solitary nature, Friedrich maintained friendships within the Dresden artistic community. He was close to the Norwegian painter Johan Christian Dahl, who settled in Dresden in 1818 and shared a house with Friedrich for many years. Dahl's more naturalistic approach to landscape may have influenced Friedrich's later work towards slightly greater immediacy, though Friedrich always retained his symbolic focus. He was also friends with Carl Gustav Carus, a physician, painter, and theorist who became one of Friedrich's most important interpreters, publishing influential essays on his art and landscape painting theory. Friedrich also knew Philipp Otto Runge, another leading German Romantic painter based in Hamburg, whose symbolic art, though different in style (focusing more on figures and floral symbolism), shared a similar spiritual intensity.

Later Life and Declining Fame

In 1818, at the age of 44, Friedrich married the 25-year-old Caroline Bommer. The marriage produced three children and seems to have brought a period of relative contentment, reflected perhaps in works like Chalk Cliffs on Rügen. He received some official recognition, being elected a member of the Dresden Academy in 1816 and appointed an associate professor in 1824 (though he hoped for a full professorship, which never materialized, possibly due to his perceived political sympathies or unconventional art).

However, from the mid-1820s onwards, Friedrich's health began to decline, and his art fell out of favour. The prevailing taste shifted towards the more optimistic and less overtly symbolic styles of Biedermeier and early Realism. His meticulous technique began to seem old-fashioned. In June 1835, he suffered a debilitating stroke, which severely limited his ability to work, particularly in oil. He increasingly turned to watercolour and sepia drawings, revisiting earlier themes with a sometimes starker, more melancholic intensity, as seen in some of his late seascapes.

He experienced growing financial difficulties and felt increasingly isolated from the contemporary art world. Caspar David Friedrich died in Dresden on May 7, 1840, at the age of 65. By the time of his death, his work was largely forgotten by the broader public, appreciated only by a small circle of friends and admirers.

Rediscovery and Legacy

For several decades after his death, Friedrich remained a marginal figure in art history. His reputation suffered further damage in the 20th century when the Nazi regime attempted to co-opt his art, interpreting his dramatic German landscapes as expressions of nationalist ideology. This association cast a pall over his work in the immediate post-war years.

However, a critical reappraisal began in the early 20th century and gained momentum after World War II. Exhibitions and scholarly publications shed new light on the depth and complexity of his art, disentangling it from political misuse. He was recognized not only as the foremost painter of German Romanticism but also as a visionary precursor to later art movements.

His emphasis on subjective experience and emotional expression resonated with the Symbolists of the late 19th century, such as Arnold Böcklin. His exploration of psychological states and dreamlike atmospheres anticipated Surrealism, influencing artists like Max Ernst. The expressive power and spiritual intensity of his landscapes also led to him being seen as a significant forerunner of Expressionism, particularly evident in the works of Edvard Munch and members of Die Brücke like Ernst Ludwig Kirchner.

Enduring Influence

Friedrich's influence extends far beyond German borders and specific movements. His elevation of landscape painting to a vehicle for profound philosophical and spiritual inquiry fundamentally changed the genre. His impact can be seen in the work of the American Hudson River School painters, such as Thomas Cole, Frederic Edwin Church, and Albert Bierstadt, who similarly depicted the sublime power and spiritual significance of the natural world, often imbued with nationalistic sentiment regarding the American wilderness.

In the 20th and 21st centuries, numerous artists have engaged with Friedrich's legacy. The metaphysical paintings of Giorgio de Chirico, with their empty spaces and sense of unease, echo Friedrich's solitary moods. Abstract Expressionist Mark Rothko acknowledged Friedrich's influence, and his large, immersive colour field paintings evoke a similar sense of the sublime and transcendent. Contemporary artists like the Icelandic-Danish Olafur Eliasson explore themes of nature and perception that recall Friedrich, while the Japanese photographer Hiroshi Sugimoto's serene, minimalist seascapes share an affinity with Friedrich's contemplative approach to the sea and sky. German artists like Gerhard Richter and Anselm Kiefer have also referenced Friedrich, grappling with landscape, history, and representation in ways that acknowledge his towering presence in German art history.

Conclusion

Caspar David Friedrich remains a compelling and profoundly moving artist. He harnessed the visual language of landscape to explore the deepest questions of human existence – life, death, faith, solitude, and humanity's place within the vastness of the cosmos. His unique fusion of meticulous observation, symbolic depth, and intense emotional resonance created images that are both distinctly of their time – the height of German Romanticism – and timeless in their appeal. Though neglected for a period, his rediscovery cemented his status as a pivotal figure in Western art, a master whose hauntingly beautiful and spiritually charged landscapes continue to captivate and inspire viewers today. His work stands as a testament to the power of art to connect the inner world of the soul with the outer world of nature.