Carl Eduard Ahrendts stands as a notable figure in the rich tapestry of 19th-century Dutch art. A painter active during a period of significant artistic transition, Ahrendts contributed to the enduring tradition of Dutch landscape and cityscape painting. His life and work offer a window into the artistic currents of his time, particularly his connection to one of the era's most celebrated landscape artists, Barend Cornelis Koekkoek. Understanding Ahrendts requires exploring his personal artistic journey, the influential figures around him, and the broader cultural environment of the Netherlands during his lifetime.

Born in 1822, Carl Eduard Ahrendts embarked on his artistic career in the Netherlands, a nation with a profound and storied history in the visual arts. The 19th century was a dynamic period for Dutch painters, who were navigating the legacy of the Golden Age masters while responding to new European artistic movements, primarily Romanticism and, later, the stirrings of Realism and Impressionism. Ahrendts's development as an artist was significantly shaped within this environment, particularly through his association with prominent figures in the Dutch art scene.

Early Influences and Artistic Formation

The tutelage under Barend Cornelis Koekkoek (1803-1862) was arguably the most formative influence on Carl Eduard Ahrendts. Koekkoek was not merely a teacher; he was widely regarded as the "Prince of Landscape Painters" in his time, a leading exponent of Dutch Romanticism. His meticulously detailed and often idealized depictions of nature, particularly woodland scenes and panoramic vistas, set a high standard for landscape art in the Netherlands and beyond. To be a student of Koekkoek meant immersion in a tradition that valued technical skill, careful observation of nature, and an ability to evoke mood and atmosphere.

Koekkoek himself was part of an artistic lineage, having studied under masters like Jan Willem Pieneman and Andreas Schelfhout, the latter being a significant figure in transitioning Dutch landscape painting from neoclassical styles to Romanticism. This educational background, emphasizing both academic principles and a romantic sensibility towards nature, would have been passed down to his pupils, including Ahrendts. The environment in Koekkoek's studio would have been one of rigorous training, focusing on drawing from nature, understanding composition, and mastering the subtle play of light and shadow that characterized Romantic landscapes.

The Koekkoek School and Its Impact

Barend Cornelis Koekkoek established a highly influential school, attracting numerous students eager to learn his techniques. His own works often featured majestic trees, dramatic skies, and carefully placed figures that emphasized the grandeur of nature. He was known for his "Koekkoek trees," gnarled oaks and stately beeches rendered with almost portrait-like precision. This attention to detail, combined with an overall harmonious composition, was a hallmark of his style.

Students like Ahrendts would have been encouraged to undertake sketching trips, directly observing the Dutch countryside, its waterways, forests, and the unique quality of its light. Koekkoek's influence extended beyond mere technique; he instilled an appreciation for the poetic qualities of the landscape. While some of his students, like Fredrik Marinus Kruseman or Johann Bernard Klompenius, developed styles closely echoing the master, others, potentially including Ahrendts, might have sought to integrate these lessons with their own evolving perspectives or other contemporary influences.

The artistic circle around Koekkoek was vibrant. His brothers, Hermanus Koekkoek Sr. and Marinus Adrianus Koekkoek, were also respected painters, specializing in marine and landscape subjects respectively, contributing to a family dynasty of artists. The competitive yet collaborative spirit of such circles often spurred artistic growth. For instance, B.C. Koekkoek himself engaged in artistic competitions, such as the Felix Meritis contest in Amsterdam, where he vied with emerging talents like Wijnand Nuyen, whose innovative style presented a challenge to established norms.

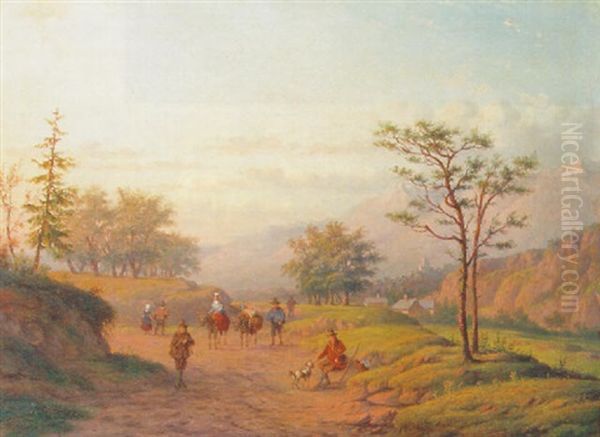

Ahrendts's Artistic Themes and Subjects

Carl Eduard Ahrendts's oeuvre, as indicated by available information, was diverse, encompassing landscapes, cityscapes, animal studies, and figural work. This breadth suggests an artist keen on exploring various facets of the visual world, a common trait among 19th-century painters who often needed to be versatile to appeal to a wider market and to fully explore their artistic capabilities.

His landscape paintings would have naturally drawn from the Dutch tradition, which celebrated the local scenery – flat polders, winding rivers, expansive skies, and charming villages. Winter scenes, a beloved subgenre in Dutch art since the 17th century, were also part of his repertoire, offering opportunities to explore the effects of snow, ice, and the stark beauty of the dormant landscape. Artists like Andreas Schelfhout, B.C. Koekkoek's teacher, excelled in winter landscapes, and this tradition was carried forward by many Romantic painters.

Cityscapes, or "stadsgezichten," also have a long and distinguished history in Dutch art. Ahrendts's engagement with this genre allowed him to capture the architectural character of Dutch towns and cities, the interplay of buildings, canals, and human activity. These works often balanced topographical accuracy with an atmospheric quality, aiming to convey the unique spirit of a place. His animal and figure paintings, though perhaps less central to his output, would have demonstrated his skills in anatomical rendering and capturing life, often integrated into his larger landscape or urban compositions.

Stylistic Considerations and Development

While directly under the influence of B.C. Koekkoek's Romanticism, the 19th century was a period of stylistic evolution. It is plausible that Ahrendts's work, while rooted in Romantic principles, may have also shown an awareness of or even incorporated elements from emerging trends. The meticulous detail and idealized beauty of high Romanticism began to give way to a more direct, unembellished observation of reality, a precursor to Realism.

The mention of Paul Joseph Constantin Gabriël (1828-1903) as part of Ahrendts's artistic circle is significant. Gabriël became a prominent member of the Hague School, a movement that emerged in the latter half of the 19th century and represented a shift towards a more realistic and atmospheric depiction of the Dutch landscape, often characterized by muted palettes and a focus on light and mood – a Dutch form of Impressionism. If Ahrendts was associated with Gabriël, it suggests he was at least exposed to these newer artistic ideas.

Therefore, Ahrendts's style might have represented a bridge or a blend. He could have retained the strong compositional structures and attention to detail learned from Koekkoek, while perhaps adopting a softer brushwork or a more naturalistic palette in some of his later works, influenced by the changing artistic climate. The information that he was "self-taught" in aspects of romantic landscapes, winter scenes, and cityscapes, despite having Koekkoek as a teacher, is intriguing. It might suggest that while he received foundational training, he continued to develop certain specializations through personal study and experimentation, perhaps drawing inspiration from a wider range of sources or developing unique approaches to these themes.

A Glimpse into His Work: Huis ten Bosch

While a comprehensive list of Carl Eduard Ahrendts's definitive masterpieces remains elusive in readily available records, one specific painting offers valuable insight into his work: Huis ten Bosch. This oil on canvas, measuring 29.5 x 42.5 cm, was created around 1850. The subject, Huis ten Bosch ("House in the Woods"), is one of the three official residences of the Dutch Royal Family, located in The Hague. Its historical and cultural significance makes it a prestigious subject for any artist.

Ahrendts's depiction of this iconic palace would have required both architectural accuracy and an ability to convey its stately presence within its wooded surroundings. Painted in the mid-19th century, this work falls squarely within the period when Romantic sensibilities were prevalent, yet the subject also lends itself to a degree of topographical precision. It is likely that Ahrendts approached the scene with the detailed execution characteristic of his training, while also imbuing it with the atmospheric qualities expected of a landscape painter of his era.

The provenance of this particular painting is also noteworthy. It is currently held in the Koninklijke Verzamelingen (Royal Collections) in Amsterdam, a testament to its quality and historical value. The records indicate it was acquired by Phillips Fine Art Auctioneers & Valuers on June 15, 1993, and subsequently became part of the Stichting Historische Verzamelingen van het Huis Oranje-Nassau (Foundation for the Historical Collections of the House of Orange-Nassau). This trajectory underscores the painting's recognition in the art market and its importance as a cultural artifact.

The Dutch Art Scene in Ahrendts's Time

Carl Eduard Ahrendts practiced his art during a fascinating period of transition in the Dutch art world. The early to mid-19th century was dominated by Romanticism, with artists like B.C. Koekkoek, Andreas Schelfhout, and Wijnand Nuyen leading the way. They revitalized landscape painting, drawing inspiration from the Dutch Golden Age masters like Jacob van Ruisdael and Meindert Hobbema, but infusing their work with the emotional intensity and picturesque qualities of the Romantic movement.

However, by the mid-century and increasingly towards its latter decades, new artistic currents began to emerge. The Barbizon School in France, with painters like Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot and Jean-François Millet, championed a more direct and unidealized approach to nature. This influenced Dutch artists, leading to the rise of the Hague School. Figures such as Jozef Israëls, Anton Mauve, Hendrik Willem Mesdag, Jacob Maris, Willem Maris, Matthijs Maris, Johannes Bosboom, and Ahrendts's contemporary Paul Joseph Constantin Gabriël, moved away from the polished finish and idealized scenes of Romanticism.

The Hague School artists favored more subdued palettes, capturing the often grey, diffused light of the Dutch coast and countryside. Their work was characterized by a sense of atmosphere, realism, and an interest in the everyday lives of peasants and fishermen. While Ahrendts's primary training was in the Romantic tradition, his active period overlapped significantly with the ascendancy of the Hague School. It is conceivable that his later works might have reflected some of these evolving sensibilities, perhaps in a more naturalistic treatment of light or a looser brushstroke, even if he remained fundamentally a Romantic painter. Other contemporaries like Charles Leickert also specialized in cityscapes and winter scenes, often with a Romantic touch but also with a keen eye for daily life.

Interactions and Artistic Community

The 19th-century art world, while competitive, was also communal. Artists often gathered in studios, academies, and societies, exchanging ideas and techniques. Ahrendts's association with B.C. Koekkoek placed him within a significant network. Koekkoek's studio in Cleves (Kleve), Germany, just across the Dutch border, became an artistic hub. The master's influence was far-reaching, not only through his direct students but also through the widespread popularity and dissemination of his works via prints and exhibitions.

The mention of Paul Joseph Constantin Gabriël in Ahrendts's circle suggests engagement with artists who were perhaps exploring different, more modern paths. Gabriël, known for his luminous landscapes and his emphasis on capturing the "mood" of the Dutch polder landscape, was a key figure in the Hague School. Such connections, even if not involving direct collaboration, would have exposed Ahrendts to ongoing debates and developments in art.

While specific records of Ahrendts's extensive interactions or collaborations with a wide array of named painters are not detailed in the provided summary, the nature of the art world at the time implies a degree of professional acquaintance and mutual awareness among artists working in similar genres or regions. Exhibitions, art dealerships, and critical reviews all contributed to a shared artistic discourse. For instance, the works of artists like Johan Barthold Jongkind, a Dutch painter who was a forerunner of Impressionism and spent much time in France, would have also been part of the broader European artistic conversation, potentially influencing Dutch artists looking for new modes of expression.

Later Career, Demise, and Legacy

Carl Eduard Ahrendts continued his artistic practice throughout the 19th century, passing away in 1902. By this time, the art world had undergone further transformations. Post-Impressionism was taking hold in France, and various avant-garde movements were beginning to challenge established artistic conventions across Europe. In the Netherlands, artists like Vincent van Gogh (though largely working abroad) and Piet Mondrian (in his early representational phase) were pushing boundaries.

Ahrendts's legacy lies in his contribution to the Dutch Romantic tradition and his role as a skilled painter of landscapes and cityscapes during a vibrant period of national artistic production. While perhaps not achieving the same level of international fame as his teacher, B.C. Koekkoek, or some of the leading figures of the Hague School, Ahrendts represents the many dedicated and talented artists who sustained and enriched their national artistic heritage.

His works, like Huis ten Bosch, serve as valuable historical documents, capturing the appearance of specific locations and reflecting the aesthetic sensibilities of their time. The preservation of such paintings in collections like the Koninklijke Verzamelingen ensures that his contribution is not forgotten and remains accessible for study and appreciation. Artists like Ahrendts are crucial for a comprehensive understanding of an artistic era, providing depth and context beyond the most famous names. They demonstrate the breadth of artistic practice and the subtle ways in which styles evolved and intermingled.

Conclusion: Appreciating Carl Eduard Ahrendts

Carl Eduard Ahrendts was a Dutch painter of the 19th century whose artistic journey was significantly marked by his tutelage under the renowned Romantic landscape painter Barend Cornelis Koekkoek. Born in 1822 and active until his death in 1902, Ahrendts worked across various genres, including landscapes, cityscapes, animal studies, and figure painting, demonstrating a versatile command of his craft.

His connection with Koekkoek rooted him firmly in the Dutch Romantic tradition, emphasizing meticulous detail, atmospheric effects, and an idealized yet observant approach to nature and urban scenes. The painting Huis ten Bosch stands as a known example of his work, showcasing his ability to render significant architectural subjects with precision and artistic sensitivity. His association with figures like Paul Joseph Constantin Gabriël also suggests an awareness of the evolving artistic landscape, particularly the rise of the Hague School with its more naturalistic and atmospheric tendencies.

While perhaps not a revolutionary figure, Carl Eduard Ahrendts was a skilled and dedicated artist who contributed to the rich artistic fabric of 19th-century Netherlands. His work reflects the high standards of craftsmanship prevalent in his time and offers a valuable perspective on the Dutch landscape and cityscape tradition. Alongside contemporaries and influential figures such as Andreas Schelfhout, Wijnand Nuyen, Hermanus Koekkoek Sr., Marinus Adrianus Koekkoek, Fredrik Marinus Kruseman, Johann Bernard Klompenius, Jozef Israëls, Anton Mauve, Hendrik Willem Mesdag, Jacob Maris, and Charles Leickert, Ahrendts played his part in a dynamic century of Dutch art. His paintings continue to be appreciated for their historical value and their quiet, enduring artistry.