François Antoine Bossuet stands as a significant figure in 19th-century Belgian art. Born in Ypres, West Flanders, in 1798 and passing away in Saint-Josse-ten-Noode, Brussels, in 1889, his long life spanned a period of immense change in Europe, both politically and artistically. Bossuet carved a distinct niche for himself as a painter primarily celebrated for his meticulously detailed and atmospheric depictions of European cities, rendered with an exceptional command of perspective. His work firmly belongs to the Romantic movement, often infused with the allure of distant lands, particularly Spain and North Africa, aligning him with the Orientalist interests of his time.

Educated at the prestigious Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts in Brussels, Bossuet honed the technical skills that would become the bedrock of his artistic practice. While the exact dates of his formal studies require careful consideration, his time at the Academy undoubtedly exposed him to the prevailing artistic currents and provided rigorous training in drawing, composition, and the principles of perspective – a discipline in which he would particularly excel. The Brussels Academy was a crucible of talent, fostering artists who would shape the identity of Belgian art following the country's independence in 1830.

Bossuet emerged as an artist dedicated to the genre of the cityscape, or veduta. This tradition, popularized by Italian masters like Canaletto in the previous century, involved detailed, often large-scale paintings of city scenes. However, Bossuet infused this genre with the sensibilities of Romanticism. His works were not merely topographical records; they aimed to capture the mood, the light, and the historical resonance of the places he depicted. He became renowned for his almost scientific precision in rendering architecture, ensuring that every column, arch, and facade was accurately portrayed according to the laws of linear perspective.

The Romantic Vision in Urban Landscapes

The core of Bossuet's extensive oeuvre lies in his cityscapes. He possessed an uncanny ability to translate the three-dimensional reality of complex urban environments onto the two-dimensional canvas. His mastery of perspective was not just a technical feat; it was integral to the immersive quality of his paintings. Viewers feel drawn into the scenes, whether looking down a bustling street, across a sunlit plaza, or towards a distant, iconic landmark. This precision lent his work an air of authenticity and documentary value, even as he employed artistic license to enhance the romantic atmosphere.

Romanticism in Bossuet's work manifests in several ways. He often chose viewpoints that emphasized the grandeur or picturesque qualities of a city. His handling of light and shadow plays a crucial role, frequently employing warm, golden light to bathe scenes, suggesting a specific time of day or evoking a nostalgic or idealized feeling. This is particularly evident in his Spanish subjects, where the strong Mediterranean sun creates dramatic contrasts. Furthermore, the inclusion of small figures within the vast architectural settings – a common trope – serves to heighten the sense of scale and the magnificence of the built environment, sometimes hinting at the transient nature of human life against the backdrop of enduring structures.

His paintings often capture cities at moments of historical significance or transition. For instance, some works reportedly depict the dismantling of the old city walls of Brussels during the 19th century. Such paintings serve as valuable visual records of urban transformation, documenting a changing world while simultaneously imbuing the scenes with a sense of historical passage, a theme resonant with Romantic preoccupations with the past.

Journeys Through Europe and North Africa

Like many artists of his era, François Antoine Bossuet was an avid traveller. His journeys across Europe and into North Africa provided him with a rich repository of subjects and significantly shaped his artistic output. He is known to have travelled extensively, visiting the Netherlands, Germany, France, Italy, Spain, and parts of North Africa. These travels were not mere holidays; they were working expeditions during which he would sketch, observe, and gather material for the highly finished oil paintings he would later complete in his studio.

Spain held a particular fascination for Bossuet, and his depictions of Andalusian cities like Seville, Granada, and Córdoba are among his most celebrated works. The legacy of Moorish architecture, the vibrant street life, and the intense southern light offered compelling subjects that aligned perfectly with the Orientalist tastes prevalent in the 19th century. Orientalism, as an artistic and cultural phenomenon, involved the depiction of Middle Eastern, South Asian, and North African subjects by Western artists, often emphasizing exoticism, sensuality, and perceived cultural differences. Bossuet’s Spanish and North African scenes fit within this broad category, showcasing his skill in capturing intricate architectural details and the unique atmosphere of these locales.

His travels to Italy furnished him with classic subjects – views of Venice, Rome, and other historic centres, allowing him to engage with the long tradition of veduta painting associated with artists like Giovanni Antonio Canal, known as Canaletto, and Bernardo Bellotto. In Germany and the Netherlands, he would have found different architectural styles and urban characters to capture, broadening the geographical scope of his work. Each journey added new motifs, colour palettes, and atmospheric effects to his repertoire, contributing to the diversity and richness of his oeuvre.

Signature Works and Artistic Techniques

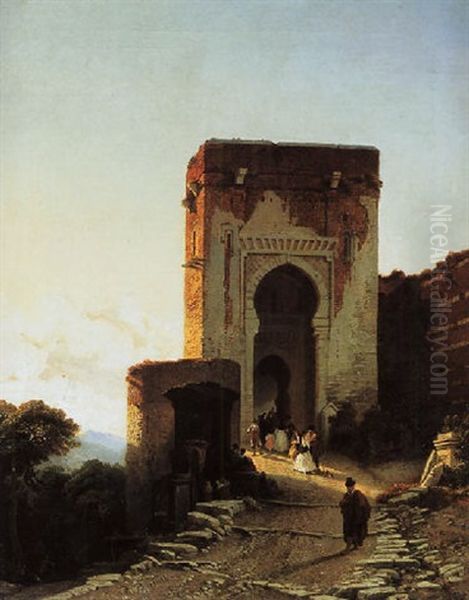

Several specific works exemplify Bossuet's style and thematic concerns. His painting Porte de Justice, Alhambra (Gate of Justice, Alhambra) is a prime example of his Spanish subjects and Orientalist leanings. It showcases his meticulous attention to the intricate details of the Moorish architecture of the Alhambra palace in Granada. The play of warm light and shadow, the careful rendering of textures, and the inclusion of small figures to emphasize the monumental scale of the gate are all characteristic features of his approach. This work captures the romantic allure of Spain that captivated so many 19th-century artists and writers.

Another notable work is Vue sur le Daro à Grenade (View over the Darro River in Granada). This painting likely combines architectural elements with a landscape view, demonstrating his versatility within the cityscape genre. It again highlights his interest in Granada, a city rich in history and picturesque scenery. Such works allowed him to explore the relationship between the urban environment and its natural surroundings, often using waterways or distant mountains to frame the composition and add depth.

Paintings like A busy Flemish Street bring his focus back to his native region. These works capture the distinct character of Belgian or Dutch towns, perhaps depicting market scenes, canals, or historic town squares. They demonstrate his ability to apply his signature style – precise perspective, atmospheric light, detailed observation – to the familiar environments of Northern Europe. These paintings often convey a sense of civic life and local identity, contrasting with the more exotic appeal of his southern subjects. His depictions of Brussels, including views documenting the removal of its medieval fortifications, serve as important historical documents of the city's modernization.

Bossuet's technique typically involved careful underdrawing, precise application of paint, and a relatively smooth finish, allowing the details of the architecture and the subtleties of light to take precedence. His colour palettes varied according to the location depicted, ranging from the cool, silvery light of the north to the warm, golden tones of the Mediterranean. Throughout his work, the unifying element is the unwavering commitment to perspective and architectural accuracy, combined with a Romantic sensibility that elevates the scenes beyond mere documentation.

Bossuet in the Context of 19th-Century Art

To fully appreciate François Antoine Bossuet's contribution, it is essential to place him within the broader context of 19th-century European art, particularly in Belgium. The 19th century was a dynamic period for Belgian art, marked by the establishment of an independent nation and a flourishing of national artistic identity, often expressed through Romanticism and later, Realism.

Bossuet worked during the heyday of Belgian Romanticism. While major figures like Gustave Wappers and Nicaise de Keyser gained fame for their large, dramatic history paintings celebrating Belgian history and heroes, Bossuet pursued a different path within the Romantic movement. His focus on the cityscape offered a quieter, though no less skilled, form of Romantic expression. His contemporaries in Belgium included Louis Gallait, another prominent history painter, and Jean-Baptiste Madou, known for his charming genre scenes of everyday life. While their subjects differed, they shared a commitment to technical skill and often a Romantic outlook.

In the specific genre of cityscape and architectural painting, Bossuet can be seen as continuing a tradition strong in the Low Countries, harking back to 17th-century Dutch masters like Jan van der Heyden or Gerrit Berckheyde, who were renowned for their detailed urban views. However, Bossuet updated this tradition with 19th-century techniques and Romantic atmosphere. Later Belgian artists like Henri Leys, initially a Romantic, moved towards historical realism, while Henri de Braekeleer developed a more intimate, light-filled realism in his Antwerp interiors and city views.

Looking beyond Belgium, Bossuet's work resonates with other European artists interested in architectural representation and the picturesque. His detailed renderings of Spain invite comparison with the work of the Scottish artist David Roberts, another prominent Orientalist painter known for his extensive travels and detailed lithographs and paintings of Egypt, the Near East, and Spain. While Roberts often worked on a grander, more dramatic scale, both artists shared a fascination with architectural detail and exotic locales.

His meticulous cityscapes also stand in contrast to the more atmospheric, light-obsessed urban views being developed by artists associated with Impressionism later in the century, such as Claude Monet or Camille Pissarro, who prioritized capturing fleeting moments and the effects of light over precise architectural detail. Bossuet remained largely faithful to an academic approach rooted in drawing and perspective, refined by Romantic sensibilities. His work can also be contextualized alongside other European cityscape specialists of the era, such as the Italian Ippolito Caffi, known for his dramatic perspectives and nocturnal scenes, or German architectural painters like Eduard Gaertner in Berlin. Even the great English Romantic J.M.W. Turner, though vastly different in style, shared an interest in depicting the atmosphere and grandeur of cities like Venice, albeit with a focus on light and elemental forces rather than precise structure.

Later Years and Lasting Legacy

François Antoine Bossuet continued to paint throughout his long life, maintaining a consistent style and high level of technical proficiency. He remained based primarily in Brussels, where he had established his reputation and likely found a steady market for his popular city views. His dedication to his craft and his specific niche ensured his place within the Belgian art scene of the 19th century. He passed away in 1889 in Saint-Josse-ten-Noode, a municipality of Brussels, leaving behind a substantial body of work.

Today, Bossuet's paintings are held in various public and private collections, particularly in Belgium. The Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium in Brussels house examples of his work, offering insight into his skill and typical subjects. His paintings can also be found in other Belgian museums, such as the Groeningemuseum (part of Musea Brugge) in Bruges, and potentially in provincial museums in France and elsewhere, reflecting the international appeal of his cityscapes during his lifetime.

His legacy rests on his position as a leading Belgian exponent of the Romantic cityscape. He successfully merged the tradition of detailed architectural painting with the atmospheric and evocative qualities of Romanticism. His works are valued not only for their artistic merit – the impressive command of perspective, the sensitivity to light and atmosphere, the meticulous detail – but also as historical documents, capturing the appearance of European and North African cities in the 19th century. He provided his audience, both then and now, with windows onto worlds both familiar and exotic, rendered with a clarity and charm that continues to appeal.

While perhaps not as revolutionary as some of his contemporaries who pushed the boundaries towards Realism or Impressionism, Bossuet excelled within his chosen field. He represents a significant strand of 19th-century art that valued technical mastery, detailed observation, and the romantic depiction of place. His paintings invite viewers to travel through time and space, exploring the streets, squares, and canals of historic cities as seen through the eyes of a dedicated and highly skilled Romantic artist.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision

François Antoine Bossuet occupies a respected place in the history of Belgian art. As a master of the cityscape, he brought the precision of architectural rendering together with the atmospheric depth of Romanticism. His extensive travels provided a wealth of subject matter, from the canals of his native Low Countries to the sun-drenched plazas of Andalusia and the historic vistas of Italy. His exceptional skill in perspective remains a hallmark of his work, creating immersive and believable urban scenes.

Though working within established genres like the veduta and engaging with popular trends like Orientalism, Bossuet developed a distinctive personal style characterized by clarity, detail, and a subtle romantic sensibility. His paintings offer more than just topographical accuracy; they convey a sense of place, history, and atmosphere. In an era of significant artistic change, Bossuet remained committed to his vision, producing a consistent and high-quality body of work that found appreciation during his lifetime and continues to be valued today. His art provides enduring glimpses into the urban landscapes of the 19th century, captured with the eye of a meticulous observer and the soul of a Romantic.